You’ll find several ghost towns near Capitol Reef that tell Utah’s pioneer story. Notom, just ten minutes south on Highway 24, was abandoned after floods devastated the 1886 settlement. Within the park itself, Fruita preserves Mormon heritage through historic orchards and the Gifford House museum. Further afield, Grafton stands as the West’s most photographed ghost town, while Silver Reef reveals where fortune-seekers discovered the geological anomaly of silver in sandstone. Each weathered structure and carved inscription offers deeper insights into the resilience that defined desert survival.

Key Takeaways

- Grafton, settled in 1859, is the West’s most photographed ghost town, abandoned by 1921 after floods and conflicts.

- Silver Reef attracted 3,000 fortune-seekers by 1879 with unique sandstone silver deposits, closing in 1891 after $25 million yield.

- Notom, established in 1886, was abandoned due to harsh conditions; a working ranch now occupies the former settlement site.

- Grafton’s 1886 schoolhouse and historic homes remain as landmarks, famously featured in the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

- Silver Reef’s restored Wells Fargo building serves as a museum, preserving the town’s geological and mining history.

Notom: A Forgotten Settlement Along Highway 24

Just ten minutes south of Highway 24, a weathered historical marker stands along Notom Road, marking the site where 23 families once carved out lives in the unforgiving Utah desert.

Notom history began in 1886 when settlers established Pleasant Creek, though the postal service rejected that name. Someone suggested “Notom”—origin unknown, meaning lost to time.

The Notom geography positioned it perfectly as a staging ground for adventures deeper into Capitol Reef Country, much like you’ll use it today.

Children attended a shared schoolhouse with neighboring Aldridge before the inevitable happened: floods and harsh reality drove everyone away.

The settlement was originally known as Pleasant Dale before postal authorities demanded a change.

Now a working ranch occupies the site, but you can still feel the ghosts of those determined pioneers who refused to surrender. Like many mining towns throughout Utah, Notom once supported hundreds of residents before economic decline forced its abandonment.

Fruita: The Thriving Mormon Community Within the Park

Today’s National Park Service maintains those same orchards, preserving what determined Mormon settlers carved from wilderness.

Their descendants returning each season to pick fruit along ancestral paths.

Franklin D. Richards established the settlement in 1878, creating a small but resilient community along the Fremont River.

The Gifford House, constructed in 1908, stands as a testament to pioneer life and now serves as a museum in Fruita’s historic district.

Grafton: The Most Photographed Ghost Town in the West

Wind whispers through the skeletal remains of Grafton, where weathered adobe walls and a two-story schoolhouse stand proof to dreams that couldn’t outlast the Virgin River’s fury.

Grafton’s crumbling adobe walls whisper tales of Mormon pioneers whose dreams shattered against the Virgin River’s relentless floods.

You’ll discover why Grafton photography has captivated countless artists—the 1886 schoolhouse frames perfectly against red cliffs, while John Wood’s 1877 home huddles beneath ancient cottonwoods.

Grafton history reads like a testimony to stubborn resilience: five Mormon families settled here in 1859, only to watch floods destroy their fields in 1862 and 1868. Indian conflicts forced abandonment in 1866.

They returned, planted cotton and wheat, buried their children in the cemetery. The population peaked at 160 before the Black Hawk Indian War decimated the settlement between 1865 and 1867. The construction of the Hurricane Canal in 1906 lured away more families seeking better irrigation prospects. By 1921, they’d finally surrendered to reality.

Now you’re free to wander where “Butch Cassidy” was filmed, touching sun-baked adobe that refuses to crumble completely.

Silver Reef: Where Silver Was Found in Sandstone

You’ll find Silver Reef’s story written in geology itself—this wasn’t some mountain vein hacked from granite, but precious metal locked impossibly in red sandstone, a phenomenon so rare that Eastern investors initially dismissed the discovery as fraud.

By 1879, nearly 3,000 fortune-seekers had flooded this ridge-scarred landscape, transforming skepticism into one of Utah’s most prosperous camps.

The mines ultimately yielded $25 million worth of ore before exhaustion and market decline forced their closure in 1891.

Today, the restored Wells Fargo building stands as your portal into that fevered era, its brick walls holding memories of ore wagons, assay offices, and the daily commerce of a town that proved the impossible. Like the Latter-Day-Saint pioneers who settled Capitol Reef in the 1800s, these miners carved communities from Utah’s unforgiving terrain, though their motivations differed vastly from those seeking agricultural sanctuary.

Unprecedented Sandstone Silver Discovery

It took eight years before scientists authenticated what Kemple knew all along.

Silver Reef became the only place on earth where you’ll find commercially mined silver from sandstone.

The deposits contained horn silver chloride disseminated throughout the rock rather than concentrated in traditional veins—nature’s rebellion against conventional geology.

The Smithsonian Institute confirmed the high concentration of horn silver in 1874, finally validating the geological anomaly that had seemed impossible.

Mining operations commenced in 1866 after Kemple’s discovery, transforming the remote sandstone reefs into a bustling frontier boomtown.

Boom Town Population Peak

News of silver locked in sandstone spread like wildfire across the frontier, and prospectors descended on this barren stretch of Utah desert with pickaxes and dreams.

By 1879, you’d have found yourself among nearly 3,000 souls transforming this once-empty landscape into a rip-roaring mining boom that rivaled anything in Nevada or Colorado.

The community growth was staggering—within thirteen years of John Kemple’s 1866 discovery, Silver Reef evolved from scattered tents to an organized municipality complete with a post office, Catholic church served by Father Lawrence Scanlan, and bustling commercial districts.

You could taste the possibility in the air, that intoxicating frontier promise where fortunes materialized from stone and every newcomer might strike it rich tomorrow.

Wells Fargo Building Today

Standing defiant against more than a century of desert winds, the 1877 Wells Fargo building rises from Silver Reef’s dusty Main Street in hand-cut red sandstone blocks that mirror the very rock formations surrounding it.

You’ll discover fortress-style metal doors and ornate arches that once guarded miners’ silver fortunes. Inside, two equal rooms maintain their original vault spaces where bullion changed hands under coal-oil lamps.

Washington County operates this National Register landmark as your gateway to the ghost town. You can explore the basement stable where stagecoach horses once stamped, then follow walking trails past crumbling foundations.

The Historic Architecture represents Southern Utah’s finest 19th-century stonework—a monument to human ambition in unforgiving territory. It’s freedom crystallized in sandstone, waiting for you to claim its stories.

Exploring the Historic Fruita Schoolhouse

Tucked beneath the towering sandstone cliffs of Capitol Reef, the Fruita Schoolhouse stands as a weathered monument to pioneer determination—a single-room structure where children once crammed shoulder-to-shoulder at homemade pine desks while their teacher juggled lessons for eight grades simultaneously.

Built in 1896 by eight families who refused to let isolation dictate their children’s futures, this log building served as school, church, and social hub for the remote Fremont River community.

You’ll find the spirit of those early settlers preserved in every chinked log and handcrafted desk—evidence that community education thrived even in Utah’s most unforgiving landscapes.

The National Register of Historic Places recognized this tribute to self-reliance in 1964, ensuring future generations can witness what frontier freedom truly required.

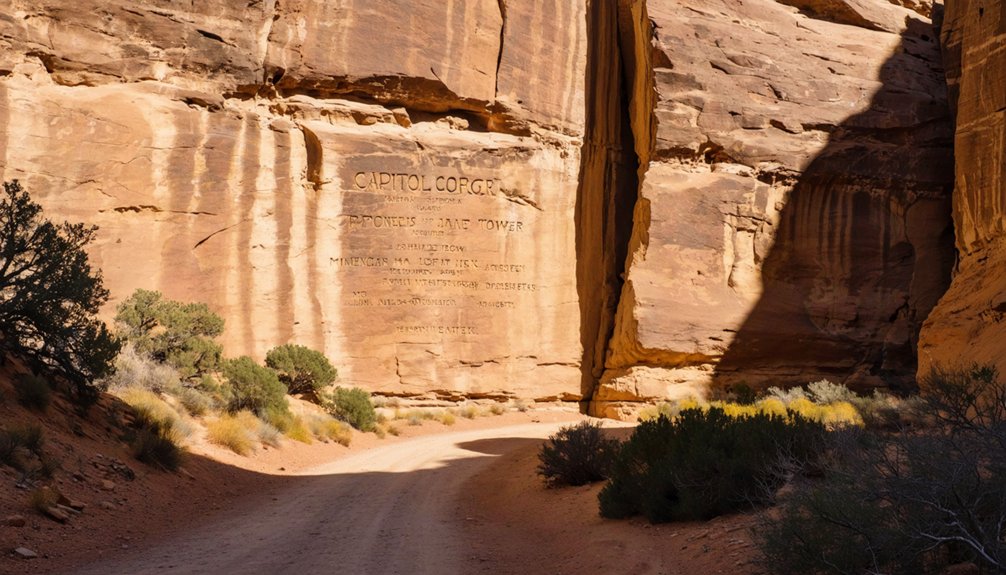

Pioneer Register at Capitol Gorge

You’ll find yourself standing before a sandstone wall inscribed with over a century of human passage, where J.A. Call and Wal. Bateman carved their names in 1871—the earliest marks of Euro-American exploration etched alongside the ancient Fremont petroglyphs that predate them by 600 years.

The Pioneer Register rises high on the north canyon wall, positioned where travelers once stood on wagon beds to stay above the flash-flood zone, their inscriptions serving as both logbook and record to the remote corridor that was the only road through the Waterpocket Fold until 1962.

A half-mile walk down Capitol Gorge‘s flat, narrow passage brings you to this protected site, where you can read the names, dates, and origins of prospectors, cowboys, and Mormon settlers who passed through this same stone corridor.

Historic Inscriptions and Signatures

Carved into the sandstone walls of Capitol Gorge, the Pioneer Register stands as a weathered tribute to the miners, surveyors, cowboys, and settlers who passed through this narrow canyon between the 1870s and early 1900s.

These pioneer inscriptions tell stories of men like J.A. Call and Wal. Bateman, whose 1871 signatures mark some of the earliest recorded passages through Capitol Reef’s rugged terrain.

You’ll find names chiseled 15–20 feet above the canyon floor—positioned above flash-flood reach—with some signatures carved by steel tools, others shot into stone with rifles.

The historical significance runs deeper than mere vandalism; this was the main wagon road through the Waterpocket Fold until 1962, and these inscriptions served as an informal logbook of westward movement and frontier ambition.

Fremont Indian Petroglyphs

Long before pioneers chiseled their names into Capitol Gorge, the Fremont people left their own marks on these sandstone walls—petroglyphs carved between 300 and 1300 CE that whisper of a culture now vanished.

You’ll find these faded figures on the left canyon wall, anthropomorphic shapes and animal forms pecked into rock with ceremonial intent. The Fremont symbolism here—possibly depicting ancestral spirits—connects to clearer panels along Highway 24, where bighorn sheep and geometric designs reveal the artistic vocabulary of these ancient farmers and hunters.

Desert varnish has dimmed many images, and petroglyph preservation remains challenging against weathering and past graffiti.

Protected now under federal law, these ghosts in stone predate Mormon settlement by seven centuries, reminding you that human restlessness has always carved its story into these canyons.

Accessing the Register

When the midday sun angles into Capitol Gorge, the Pioneer Register appears as a gallery of shadows—names and dates carved shoulder-high and higher, clustered roughly half a mile from where you’ll leave your car at the end of the unpaved gorge road.

Trail navigation is straightforward: follow the wash east, scanning the north wall where pioneer inscriptions climb toward the overhang. No signs mark the exact spot, but cairns and worn ground signal where others have stopped to look up.

The walk is flat, easy, demanding only attention to sky if clouds threaten—flash floods close this corridor fast.

You’ll stand where wagon drivers once paused, adding their mark to stone, free to pass but forbidden now to carve your own.

The Blue Dugway Road: A Historic Route Through the Desert

Stretching across the harsh Mancos shale hills like a scar on sun-baked skin, the Blue Dugway Road earned its name from the distinctive azure-gray terrain it traversed.

You’ll find few historic roadways as unforgiving as this precarious two-rut track that connected Fruita to Caineville and Hanksville. Since Elijah Cutler Behunin first cleared it in 1883, the route served gold miners, livestock herders, and Mormon settlers who refused to let desert landscapes dictate their destiny.

Desert pioneers carved their passage through Blue Dugway’s merciless terrain, proving that determination could triumph over even Utah’s most hostile landscapes.

When Wayne County designated it Utah’s first state road in 1910, they acknowledged what travelers already knew—this treacherous passage represented freedom’s price.

The roadbed clung to washes at the base of towering Wingate cliffs, descending through Blue Dugway terrain where one wrong turn meant disaster.

Planning Your Ghost Town Adventure Near Capitol Reef

How do you transform a scattered collection of crumbling homesteads and weather-beaten structures into a coherent exploration of southern Utah’s settlement history?

Begin your ghost town exploration at Fruita’s schoolhouse, where you’ll walk through an operational building that served 23 students before Capitol Reef became a national park.

As you continue your adventure, consider exploring abandoned towns near Sequoia that tell stories of their forgotten past. These hidden gems are often surrounded by stunning landscapes, making the journey not only a historical exploration but also a visual delight. Don’t forget to bring your camera, as you’ll want to capture the haunting beauty of these deserted locations.

Chart eastward to Notom, your launching point for backcountry routes threading through Capitol Reef’s less-traveled margins.

Extend south to Grafton’s cinematic landscapes where Butch Cassidy once rode across silver screens, then northwest to Silver Reef’s sandstone-embedded silver veins.

Historical preservation varies dramatically—Fruita maintains active orchards while Grafton stands frozen in 1860s architecture.

You’ll need high-clearance vehicles for remote sites, detailed maps for unmarked roads, and respect for fragile structures that won’t survive careless hands.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Caused Most Ghost Towns Near Capitol Reef to Be Abandoned?

Relentless flooding decimated settlements—Caineville saw disasters every two years by 1900. You’d face environmental challenges washing away your livelihood, while economic decline from failed crops forced families to abandon their homesteads for survival elsewhere.

Are Any Ghost Town Buildings Near Capitol Reef Safe to Enter?

You shouldn’t enter any ghost town buildings near Capitol Reef without professional assessment. Building conditions range from unstable ruins to flood-damaged structures, and safety precautions demand treating all abandoned interiors as hazardous until proven otherwise.

Which Ghost Towns Require Fees or Permits to Visit?

You’ll find visiting regulations delightfully simple here—only Aldridge requires Capitol Reef’s entrance fees since it’s inside park boundaries. Caineville, Mesa, and Clifton remain gloriously free, though you might need landowner permission on private parcels.

How Long Does It Take to Visit All Ghost Towns?

You’ll need six to eight hours for thorough ghost town exploration around Capitol Reef, though savoring each site’s historical significance—from Fruita’s orchards to Notom’s windswept ruins—rewards those who take one and a half days to truly wander freely.

Can You Camp Overnight at Ghost Town Sites Near Capitol Reef?

You can’t camp overnight at ghost town sites within Capitol Reef’s boundaries—camping regulations restrict overnight stays to designated campgrounds only. However, you’ll find dispersed camping freedom on nearby BLM land surrounding these historic remnants.

References

- https://www.visitutah.com/things-to-do/history-culture/ghost-towns

- https://www.utah.com/things-to-do/attractions/old-west/ghost-towns-in-utah/

- https://www.myutahparks.com/basics/history/historic-towns/

- https://capitolreefcountry.com/notom/

- https://utahguide.com/utah-ghost-towns-and-mining-towns/

- https://welovetoexplore.com/tag/ghost-towns/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ut-fruita/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fruita

- https://capitolreefcountry.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dCg_xiclHxA