You’ll find over a dozen authentic ghost towns within 150 miles of Grand Canyon National Park, relics of Arizona’s 1860s-1940s mining boom. Chloride, founded in 1862-1863, stands as the state’s oldest continuously inhabited mining camp with structures dating to 1899. Cerbat served as Mohave County’s administrative center from 1871 until its 1912 abandonment, while Vulture City produced 340,000 ounces of gold before closing in 1942. Each settlement reveals distinct chapters of frontier history, with preserved buildings, cemeteries, and mine workings awaiting exploration throughout the high desert corridor.

Key Takeaways

- Gray Mountain Trading Post sits along Route 89-A north of Flagstaff, featuring murals from the Painted Desert Project on abandoned buildings.

- Chloride, Arizona’s oldest continuously inhabited mining town founded 1862-1863, preserves authentic 1899 structures including the Dead Ass Saloon and Jim Fritz Museum.

- Cyanide Springs is a recreated 1899 mining camp within Chloride, featuring gunfight reenactments and historic cemetery with abandoned mine workings nearby.

- Vulture City, discovered in 1863, produced 340,000 ounces of gold before closing in 1942 and once housed 5,000 residents at its peak.

- Accessing remote ghost towns requires proper planning: bring ample water, have higher clearance vehicles for dirt roads, and expect minimal services.

Historic Mining Towns in the Cerbat Mountains

Gold and silver discoveries in the Cerbat Mountains during the 1860s triggered the establishment of mining camps that would evolve into permanent settlements by the early 1870s.

The 1860s gold and silver strikes in the Cerbat Mountains sparked mining camps that became permanent towns within a decade.

You’ll find that Cerbat settlement—named for the bighorn sheep that once roamed these ranges—emerged as the region’s administrative center when it became Mohave County’s seat in 1871.

The mining operations here weren’t modest ventures: three principal mines (Esmeralda, Golden Gem, and Vanderbilt) extracted millions in precious metals.

By 1872, the town supported essential infrastructure including five smelters, an assay office, and professional services, despite never exceeding one hundred residents.

The Golden Gem alone produced $400,000 worth of ore between 1871 and 1907.

Ore from these mines was transported via wagon to the Colorado River for smelting at distant facilities.

When the county seat transferred to Mineral Park in 1873, Cerbat’s prosperity ended, with mines closing after 1887.

The post office closed in 1912, marking the final chapter of Cerbat’s existence as a functioning community.

Cyanide Springs: A True Desert Ghost Town

You’ll find Cyanide Springs constructed as a faithful recreation of an 1899-era mining camp within modern Chloride, featuring relocated period structures including the Dead Ass Saloon, a bank façade, and miners’ cabins that once housed families working the surrounding silver and turquoise claims.

These buildings anchor a streetscape designed to interpret the boom years that followed the 1873 Hualapai treaty and the 1910 arrival of the Western Arizona Railway, which served local mines until its 1931 abandonment.

The site sits along Chloride’s main route, accessible via a paved road from US-93 between Kingman and the Grand Canyon corridor, with the historic cemetery and abandoned mine workings visible on the town’s desert outskirts. The complex includes a historic gunsmith shop dating from 1874, one of the oldest commercial structures in the area.

The venue hosts Old West gunfight reenactments throughout the year, drawing visitors who come to experience Chloride’s frontier heritage through these dramatic performances.

Mining-Era Historic Structures

Although prospectors discovered silver chloride deposits in the 1840s, Chloride’s formal founding didn’t occur until 1862-1863, establishing what would become Arizona’s oldest continuously inhabited mining town.

You’ll find authentic structures from 1899 showcasing Old West architecture, including the Dead Ass Saloon and Jim Fritz Museum—originally a miners’ boarding house now displaying period furnishings maintained by the Chloride Historical Society.

The historic preservation efforts extend to the 1917 jail, electrified in 1937, and rustic cabins that once sheltered mining families. Today these buildings operate as shops generating funds for mining heritage conservation.

The Chloride Cemetery’s weathered tombstones mark early residents’ graves, while the 1916 Baptist Church—rebuilt from an 1891 Methodist Episcopal structure—remains Arizona’s oldest continuously operating church. The town’s connection to regional mining operations was facilitated by the Arizona and Utah Railway, constructed in 1899 to transport ore from Chloride and nearby areas until its abandonment in 1931. Nearby Cyanide Springs features murals painted by Roy Purcell in the 1960s and repainted in the 1980s, providing a distinctive artistic element to the desert landscape.

Accessing the Remote Site

While Chloride’s preserved structures anchor the town’s mining heritage, reaching Cyanide Springs—the reenactment “old-west town” set behind the central park—requires traversing the remote high-desert corridor northwest of Kingman.

You’ll navigate U.S. 93 approximately 23–25 miles, following signed turnoffs onto paved roads suitable for standard vehicles under normal conditions. Road conditions deteriorate beyond the townsite; dirt segments ascending toward desert murals demand higher clearance and dry-weather timing to avoid monsoon washouts.

Visitor services remain minimal. Chloride’s general store supplies basic provisions, while the Jim Fritz Museum and visitor center operate most Saturdays with limited hours. The town also maintains the oldest continually-run post office in Arizona, serving as a functional reminder of its enduring community.

Full amenities—fuel, lodging, medical care—concentrate in Kingman, a half-hour return drive. Plan accordingly: carry ample water, verify gunfight schedules post-COVID, and budget daylight hours for this 4,000-foot elevation outpost where emergency response remains distant. The town features historical markers and information available at the visitor center, reflecting its mining legacy from when the settlement peaked at over 2,000 residents.

Chloride: Arizona’s Oldest Continuously Inhabited Mining Camp

Since silver chloride deposits drew prospectors to the Cerbat Mountains around 1862–1863, Chloride has maintained its claim as Arizona’s oldest continuously inhabited mining camp.

Founded when silver seekers arrived in 1862–1863, Chloride stands as Arizona’s oldest mining camp with continuous habitation.

You’ll find Chloride history rooted in conflicts with Hualapai people that delayed development until the 1870 treaty enabled expansion. The town became Mohave County seat in 1871, reflecting its regional significance during peak years when 72–75 mines extracted silver, gold, lead, zinc, and turquoise.

Between 1900–1920, populations reached 2,000–5,000 residents. Though mines shuttered in 1944 amid falling metal prices, Chloride never emptied completely. A devastating fire in the 1920s destroyed much of the town, with renowned Western writer Louis L’Amour among those who helped extinguish the blaze.

Today’s 300-plus residents preserve this mining heritage through the post office operating since 1893, historical society landmarks, and a working 1939 Ford fire engine—tangible evidence of unbroken occupation spanning 160 years.

Gray Mountain: A Modern Roadside Relic

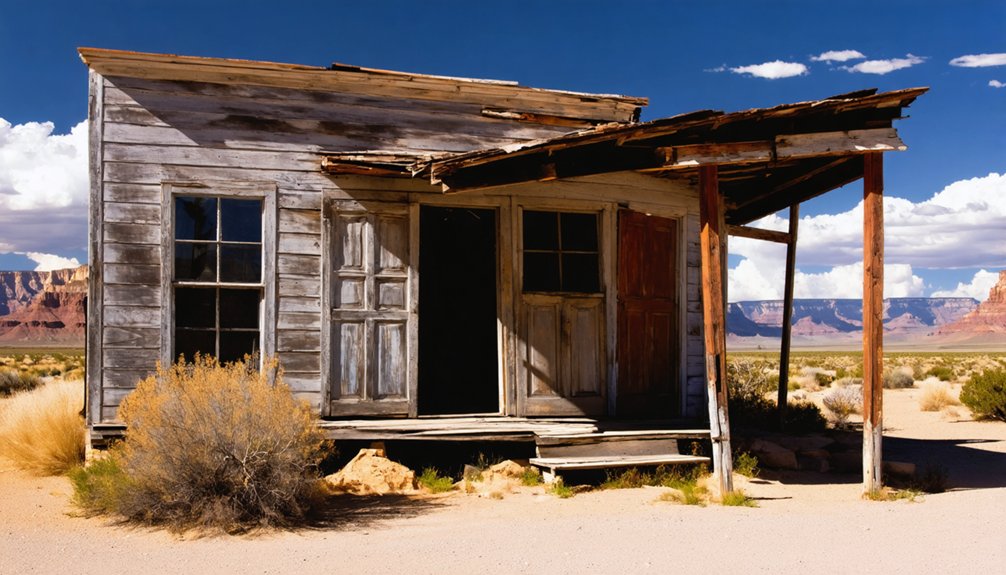

Unlike mining camps abandoned in the 19th century, you’ll find Gray Mountain represents a different kind of ghost town—one born from mid-20th-century automobile tourism and left behind by shifting travel patterns.

If you stop along U.S. Highway 89 today, you’ll encounter the skeletal remains of what was once a thriving roadside cluster centered on the Gray Mountain Trading Post, opened in 1935 to serve travelers bound for the Grand Canyon and nearby Navajo communities.

Among the broken windows and deteriorating motel structures, you’ll discover an unexpected cultural layer: the Painted Desert Project‘s vibrant murals transforming abandoned buildings into open-air galleries since the early 2010s.

Abandoned Highway Trading Post

Along Route 89-A north of Flagstaff, the abandoned Gray Mountain Trading Post marks a critical junction where commercial highway culture intersected with Navajo Nation borders.

You’ll find this two-story structure strategically positioned where travelers once stopped between Monument Valley and Grand Canyon. The trading post operated under government license after 1868, serving both Native communities and Anglo tourists through its unique architectural design.

Its lower story housed merchandise while residential quarters occupied the upper floor, with corrals accommodating horses and sheep.

Post-WWII shifts toward cash economies and automobile-dependent shopping centers eroded its customer base. The COVID-19 pandemic eliminated remaining tourism, accelerating the site’s deterioration.

This abandoned commerce now represents the obsolescence of roadside trading posts that once anchored Navajo Nation’s economic transformations.

Painted Desert Project Murals

The Gray Mountain motel complex transformed from commercial failure into public canvas when Dr. Chip Thomas launched the Painted Desert Project in 2009.

You’ll find large-format wheat-pastes of Navajo elders and youth covering the derelict walls, visible from Highway 89’s high-traffic corridor between Flagstaff and Grand Canyon.

Thomas began self-funding photographic installations, then invited international muralists starting in 2012.

Each piece requires consent from property holders and collaboration with Diné residents.

The mural storytelling addresses Indigenous identity, land connection, and environmental justice—recently including COVID-19 health messaging.

This cultural revitalization supports roadside vendors by drawing travelers to nearby stands.

Desert exposure causes continual fading and repainting, reinforcing the site’s ephemeral character as both ghost town and living narrative surface across the Western Agency.

Vulture City: Arizona’s Richest Gold Mine Legacy

When prospector Henry Wickenburg discovered a rich gold-bearing quartz vein in central Arizona’s desert in 1863, he set in motion the development of what would become the territory’s largest and most productive gold mine.

Vulture City emerged around the workings, swelling to 5,000 residents by the late 1860s. Between 1863 and 1942, the mine yielded 340,000 ounces of gold and 260,000 ounces of silver—a mining legacy valued between $30 million and $200 million in period dollars.

You’ll find this output didn’t just enrich investors; it catalyzed Phoenix’s growth by reviving ancient irrigation canals and establishing Grand Avenue as a supply corridor.

Despite ownership changes, sheriff’s sales, and a brief 1911 revival, federal wartime orders shuttered operations permanently in 1942.

Goldfield Ghost Town and the Superstition Mountains

- Arizona’s only operational 3-foot narrow-gauge railroad winds through desert landscape

- Underground mine tours reveal 1890s-era extraction methods

- Gunfight re-enactments echo across Main Street

- Gold panning stations invite personal prospecting attempts

- Historical museum archives preserve dual-era mining documentation

You’ll discover freedom exploring this twice-abandoned settlement’s documented past.

Planning Your Ghost Town Route From Grand Canyon

While Goldfield’s narrow-gauge railroad offers concentrated historical immersion, optimizing your ghost town exploration requires strategic route planning from Grand Canyon’s southern rim.

You’ll find Jerome, America’s Largest Ghost Town, positioned 60 miles south on Cleopatra Hill—once housing 15,000 residents during the early 1900s copper boom.

From there, Route 66 history beckons westward through Kingman’s corridor, where Hackberry (established 1874) and Cyanide Springs (founded 1899) await along the Mother Road.

Hackberry thrived as a silver mining destination before transforming into an iconic service station stop, while Cyanide Springs maintains authentic isolation via dirt roads from Chloride.

For southern routing, Vulture City near Wickenburg operates October through May, preserving sixteen original 1800s structures until wartime directives shuttered operations in 1942.

Essential Tips for Visiting Remote Arizona Ghost Towns

Before venturing into Arizona’s remote ghost towns, you’ll need thorough preparation that addresses the unique challenges these abandoned settlements present.

These sites require specific safety measures and exploration gear to navigate successfully.

Proper equipment and safety protocols are non-negotiable when exploring Arizona’s abandoned settlements and their unstable structures.

Essential supplies for your expedition:

- Sturdy footwear and protective clothing designed for unstable terrain and rusty remnants

- Ample water, food, and emergency provisions since facilities don’t exist in these remote locations

- Communication plan detailing your itinerary with someone reliable, given limited cell reception

- Research documentation including permits, access restrictions, and current road conditions from historical societies

- Navigation tools as ghost towns aren’t well-marked and boundaries can be unclear

Leave artifacts undisturbed—they’re shared heritage.

Stay on established trails, pack out everything you bring, and maintain distance from wildlife and hazardous mine shafts.

Best Times to Explore Ghost Towns Near the Grand Canyon

Once you’ve assembled your gear and safety provisions, timing your ghost town expedition correctly separates a rewarding historical encounter from a miserable or hazardous outing.

The best season spans March through May and late September through October, when daytime temperatures hover in the 60s–70s°F and stable weather conditions prevail. These shoulder months sidestep summer’s brutal heat—often exceeding 100°F at lower-elevation sites—and monsoon thunderstorms that transform dirt access roads into impassable mud.

Winter (December–February) offers solitude but introduces snow, ice, and shortened daylight that obscure structural hazards and close remote routes.

Summer exploration demands early-morning or near-sunset windows to avoid heat shimmer and flash-flood risk. Schedule midweek visits whenever possible; weekends and major holidays saturate Grand Canyon highways, delaying your arrival at distant mining camps and historic districts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Pets Allowed at Ghost Town Sites Near Grand Canyon?

Pet policies vary by site—public-land ghost towns generally allow leashed pets outdoors, while commercial reconstructed attractions set independent rules. You’ll find pet-friendly sites on BLM land, but expect restrictions inside historic buildings and during special events.

Can I Camp Overnight at Abandoned Ghost Town Locations?

Overnight camping isn’t permitted—most ghost towns near Grand Canyon lack legal camping regulations allowing stays, offer zero ghost town amenities, and sit on protected federal or private land where trespassing laws apply, restricting your freedom to roam after dark.

Do Ghost Towns Near Grand Canyon Charge Admission Fees?

Most ghost towns near Grand Canyon don’t charge admission fees; you’ll find free access to streets and ruins. Admission pricing applies only at commercial attractions or state parks, reflecting each site’s historical significance and preservation model.

Is Cell Phone Service Available at Remote Ghost Town Sites?

No, you’ll find virtually no cell service at remote ghost town sites near Grand Canyon. Terrain blocks signals, carriers lack towers in backcountry zones, and coverage maps overstate service—satellite communicators remain your reliable option.

Are Guided Ghost Town Tours Available From Grand Canyon?

You’ll find guided tours departing Williams (November–March) covering Jerome’s historical significance in seven-hour excursions, while Las Vegas operators offer combined Grand Canyon West trips featuring ghost town stops—giving you freedom to choose your adventure’s starting point.

References

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/03/historic-old-west-towns-in-arizona.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9sMHmeDyqLk

- https://vulturecityghosttown.com

- https://goldfieldghosttown.com

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g28924-Activities-c47-t14-Arizona.html

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowTopic-g143028-i157-k562164-Ghost_towns-Grand_Canyon_National_Park_Arizona.html

- https://www.usawelcome.net/news/explore-ghost-towns-west-usa.htm

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/az-cerbat/

- https://www.explorekingman.com/blog-Mining-History/

- http://www.apcrp.org/CERBAT/Cerbat_Cem_mast_text.htm