You’ll find several authentic ghost towns within 90 minutes of Saguaro National Park, remnants of Arizona’s 1880s-1920s mining boom. Fairbank, established in 1881, served Tombstone’s silver district along the San Pedro River. Gleeson’s Copper Belle Mine ruins sit on the Ghost Town Trail accessible via paved Gleeson Road. Courtland represents the volatile copper economy with scattered foundations, while Pearce retains operating buildings from its 1894 gold rush origins. Each site requires preparation—bring water, offline maps, and fuel—as you’ll encounter zero services amid these historical corridors where Arizona’s mineralogical legacy remains preserved in stone and memory.

Key Takeaways

- Gleeson, located on the Dragoon Mountains’ south flank, is accessible as a side trip from Saguaro National Park via Gleeson Road.

- Fairbank, established in 1881, served Tombstone’s silver district and is now managed by the Bureau of Land Management for conservation.

- Pearce, founded in 1894, peaked at 1,500 residents by 1919 and retains operating commercial buildings as a semi-ghost town.

- Courtland, founded in 1909 during the copper boom, is now completely abandoned with zero residents and scattered ruins.

- No services exist at ghost town sites; visitors must bring water, fuel, offline maps, and prepare for desert conditions.

Exploring Arizona’s Historic Mining Belt

When you stand at the edge of Saguaro National Park today, you’re looking at more than a Sonoran Desert preserve—you’re positioned along the southeastern segment of Arizona’s northwest-trending metallic mineral belt, a geological corridor that stretches from the Mexican border to beyond Prescott.

This belt, forged by granitic intrusions 70–55 million years ago, created porphyry copper systems loaded with silver, gold, lead, and zinc. By 1912, Arizona operated 445 active mines and 11 smelters, producing $67 million annually—roughly $1.4 billion today.

That mining history left behind dozens of ghost towns, their ruins now scattered across the basin ranges surrounding Tucson. Understanding this mineral legacy is essential for anyone serious about ghost town preservation and authentic desert exploration. The region’s copper dominance extended beyond precious metals—copper-bearing minerals like turquoise, azurite, and malachite became signature specimens that defined Arizona’s mineralogical identity. In the Prescott National Forest alone, operations like the Golden Turkey Mine produced gold, silver, lead, zinc, and copper through 2,000 feet of workings from 1923 to 1949.

Fairbank: A Railroad Ghost Town on the San Pedro River

Twenty-two miles due east of Saguaro National Park’s Rincon Mountain District, the railroad town of Fairbank took root on the east bank of the San Pedro River in 1881, not as a mining camp but as the critical supply artery connecting Tombstone’s bonanza silver district to the outside world.

Named for Chicago financier Nathaniel Kellogg Fairbank, this strategic junction ultimately hosted four separate railroads, moving ore, cattle, and passengers between remote mines and national markets.

Fairbank’s four converging rail lines transformed a dusty river crossing into southeastern Arizona’s indispensable commercial gateway during the territorial mining boom.

Fairbank history peaked around 1890 with 300 residents, five saloons, a Wells Fargo office, and stage connections radiating across southeastern Arizona.

Railroad significance culminated in the 1900 shootout when express messenger Jeff Milton repelled the Burt Alvord gang’s train robbery attempt.

Floods, mine closures, and shifting freight patterns emptied the town by mid-century, leaving foundations scattered across creosote flats.

The 1890 San Pedro River overflow devastated the town but residents successfully rebuilt despite ongoing challenges including disputed land titles. The Bureau of Land Management acquired the townsite in 1987, establishing a conservation area where restored buildings including the original schoolhouse now serve as a museum interpreting the settlement’s railroad heritage.

Gleeson: Copper Mining Ruins Along the Ghost Town Trail

You’ll find Gleeson approximately 16 miles east of Tombstone, where John Gleeson’s 1900 Copper Belle Mine once anchored a community of 500 residents during the early twentieth-century copper boom.

The town’s restored 1910 jail now serves as a small museum, standing alongside the cemetery and scattered building ruins that mark this copper mining settlement’s rapid rise and decline.

Access requires traversing rural dirt roads that follow the original routes serving mines like the Silver Belle, Mystery, and Brother Jonathan before railroad abandonment in 1932 isolated the community completely.

The Chiricahua Apache tribe once inhabited this area and were known for turquoise mining before the copper boom transformed the landscape.

A devastating 1912 fire destroyed 28 buildings, though the resilient mining community quickly rebuilt to continue operations through the World War I copper production boom.

Early 1900s Mining Boom

Irish prospector John Gleeson struck copper in the Turquoise area around 1900, transforming an abandoned turquoise mining settlement into one of southeastern Arizona’s most productive mining camps.

You’ll find evidence of the Copper Belle Mine, Gleeson’s first patented claim, which sparked rapid development. The town relocated three miles south to flatland for better water access, and by October 1900, a post office served 500 miners.

Multiple operations—Silver Belle, Brother Jonathan, Defiance, and Pejon—worked simultaneously, backed by major companies including Copper Queen and Leadville.

The 1909 railroad spur connecting to Southern Pacific transformed these historic settlements into efficient production centers. When World War I drove copper demand skyward, Gleeson’s mines operated at full capacity, cementing the town’s reputation in copper mining history.

The mines played out by 1940, and the post office closed in March 1939, marking the end of Gleeson’s commercial operations. Today, the restored Gleeson Jail serves as a small museum, preserving the town’s mining heritage.

Jail and Cemetery Remains

Among Gleeson’s scattered ruins, the town’s concrete jail stands as the most enduring monument to frontier law enforcement in southeastern Arizona’s copper camps.

Built in 1910 as a two-cell reinforced structure, it replaced earlier improvised methods—including chaining prisoners to a “jail tree.” The jail history includes a 1917 bootlegging incident where confiscated whiskey barrels sparked break-in attempts before authorities poured the liquor onto the street.

Local volunteers restored this roofless, graffiti-scarred ruin into a small museum displaying mining-era photographs and artifacts. The jail now opens monthly on the first Saturday and by appointment for visitors interested in exploring this piece of frontier history.

Beyond town, you’ll find Gleeson Cemetery on the outskirts, where miners and families rest beneath formal headstones and simple rock mounds.

Cemetery preservation efforts maintain this physical record spanning the late 1800s through mid-1900s, documenting the community’s rise and decline.

Rural Access and Logistics

Gleeson sits along the Ghost Town Trail between Courtland and Pearce, accessed primarily via Gleeson Road—a paved east-west route connecting the Tombstone area with Elfrida and the US-191 corridor.

You’ll find this remote townsite on the Dragoon Mountains‘ south flank, reachable as a side trip from Saguaro National Park through Tombstone and Pearce. A railroad spur completed in 1909 once linked Gleeson to the Southern Pacific system but was abandoned in 1932, shifting access routes entirely to automobile traffic.

Today’s rural logistics require self-sufficiency—no services exist on-site. Fuel up in Tombstone, Pearce, or Elfrida before venturing out.

While Gleeson Road handles standard vehicles, some spur tracks to ruins remain unpaved and rough. Private fences restrict portions of the townsite, though key structures remain visible from public roadway vantage points.

Courtland: An Abandoned Boomtown Frozen in Time

Today, you’ll find a genuine ghost town—zero residents, scattered ruins documenting thirty-three years of desert ambition. Founded in 1909 during the copper boom, Courtland’s rapid rise and fall epitomizes the volatile mining economy of early twentieth-century Arizona.

Pearce: Gold Rush Legacy and Semi-Ghost Town Charm

Where Sulphur Springs Valley meets the Dragoon Mountains, Pearce stands as Arizona’s most accessible semi-ghost town—a settlement that hasn’t fully surrendered to abandonment.

Pearce history began in 1894 when Cornish miner James Pearce discovered gold, triggering a stampede that produced $8 million in silver and $2.5 million in gold from the Commonwealth Mine’s 20 miles of underground workings.

By 1919, 1,500 residents filled its streets, saloons, and dance halls, effectively replacing Tombstone as the region’s Wild West epicenter.

The mining heritage lives on through intact commercial buildings, the old jail, and schoolhouse along Ghost Town Trail.

Unlike completely abandoned camps, you’ll find a few shops still operating among the weathered storefronts—proof that some Arizona settlements refuse to die entirely.

Planning Your Ghost Town Day Trip From Tucson

Your ghost town circuit from Tucson hinges on choosing a compass quadrant—east toward the San Pedro Valley’s Charleston and Fairbank, south through Patagonia to Harshaw and Mowry, or north via Red Rock to SASCO’s smelter ruins.

You’ll need offline maps, water, spare fuel, and confirmation of current road conditions, since many approach roads require high clearance and cell service vanishes beyond the highway corridors.

Land status varies from Forest Service tracts to BLM parcels and private mining claims, so respect posted signs and carry permits when visiting sites like Kentucky Camp on Coronado National Forest land.

Route and Timing Strategies

Because ghost towns cluster in distinct corridors southeast of Tucson, planning a successful day trip hinges on understanding the natural geography that once shaped mining booms—and now shapes your route.

Three corridor strategies maximize both historical preservation sites and ghost town photography opportunities:

- San Pedro Loop – Fairbank and Charleston ruins via AZ‑80, allowing 1.5–2 hours per site with morning light ideal for adobe structures.

- Cochise County Triangle – Gleeson, Courtland, and Pearce form a connectable trail requiring 30–60 minutes each, best tackled clockwise to avoid backtracking.

- Ruby Standalone – This remote site demands a dedicated half-day with early departure, given unpaved access roads and extensive walking grounds.

Departing Tucson by 7 a.m. puts you on-site before midday heat, with fuel stops in Benson critical before pushing deeper into ghost town corridors.

Essential Supplies and Safety

Although Tucson’s proximity to abandoned mining camps suggests casual exploration, the harsh Sonoran Desert environment surrounding these ghost towns demands preparation rivaling backcountry expeditions.

Your hydration strategies must account for 2-3 liters per person daily, supplemented with electrolyte replacements as temperatures frequently exceed 90°F. Pack refillable bottles since ghost towns like Gleeson and Courtland offer zero facilities.

Critical safety precautions include downloading offline maps—cellular service vanishes in southeastern Arizona’s remote corridors. Carry thorough first aid supplies addressing puncture wounds from rusted structures and desert vegetation.

Your vehicle needs full fuel tanks, spare tires, and emergency equipment before accessing dirt roads. Pack wide-brimmed hats, SPF 30+ sunscreen, and sturdy boots with ankle support.

Document emergency contacts and nearest hospital locations before departure into these unforgiving landscapes.

Permits and Access Rules

Most ghost towns near Tucson sit on a patchwork of jurisdictional boundaries that shift between Bureau of Land Management holdings, state trust lands, and private property—a legacy of Arizona’s complex mining claim history.

You’ll need to verify ownership before exploring each site.

Research these access guidelines before departure:

- Contact the BLM Tucson Field Office for current status on mining district access

- Check Arizona State Land Department records for trust land restrictions requiring permit application

- Respect posted private property boundaries—many historic sites remain under claim

Saguaro National Park rangers maintain updated information on adjacent ghost town accessibility.

County historical societies archive original townsite maps showing legal boundaries.

Remember that trespassing charges undermine everyone’s access to these cultural resources.

Document your research to demonstrate good faith exploration.

What to Expect at Southern Arizona Ghost Town Sites

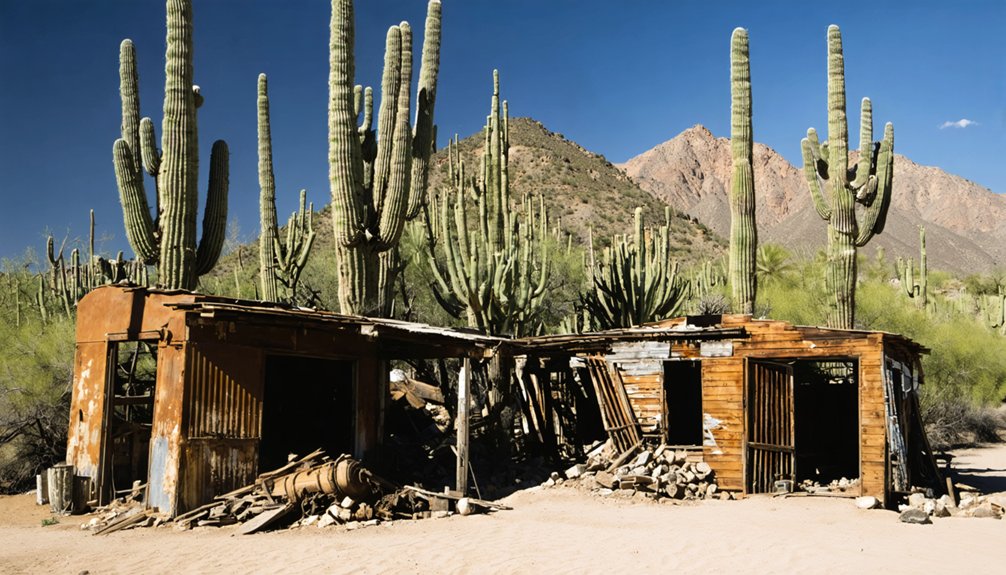

Exploring Southern Arizona’s ghost towns near Saguaro National Park means encountering landscapes where history survives in fragments rather than intact tableaus.

You’ll find stone foundations, crumbling adobe walls, and scattered mining equipment—not reconstructed attractions. Most sites sit on BLM or National Forest land with minimal facilities: dirt pullouts for parking, no restrooms, and rarely any signage.

Ghost town photography thrives here amid saguaro-studded backdrops and unrestored ruins, but historical preservation requires your vigilance. Don’t touch unstable masonry, avoid open mine shafts, and leave artifacts untouched—federal law protects what remains.

Desert hazards—rattlesnakes, extreme heat, sparse shade—demand preparation. Some areas border smuggling routes; stay alert.

Expect solitude, self-reliance, and the reward of unmediated connection to Arizona’s mining past.

Best Time to Visit and Road Conditions

- Summer monsoons (July–September) flash-flood washes, leaving clay ruts impassable for days.

- Winter ice patches above 4,000 feet lock shaded canyon approaches at dawn.

- Cell coverage ends beyond pavement, so mechanical failure becomes a survival scenario.

High-clearance vehicles and early-morning starts keep you autonomous on backcountry routes linking ghost towns to Saguaro’s iconic forests.

Combining Ghost Town Exploration With Desert Landscapes

Because Saguaro National Park anchors Tucson’s ecological identity while Cochise County ghost towns scatter across alteration zones ninety miles southeast, a combined loop delivers sharp desert contrasts within a single day’s drive.

You’ll photograph dense saguaro forests on Rincon Mountain bajadas, then shift to open grasslands and mesquite scrub around Tombstone and Fairbank—a visual change that captures Sonoran-to-Chihuahuan desert ecology in seventy road miles.

Ghost town photography improves dramatically when you frame weathered adobe ruins against wide sky and distant ranges instead of uniform cactus stands. Fairbank’s San Pedro riparian corridor injects green cottonwood galleries into otherwise tan hillsides, while the Ghost Town Trail’s rolling scrub offers unobstructed sunset compositions.

Frame crumbling adobe against open sky and distant peaks rather than repetitive cactus—the arid backdrop amplifies weathered textures.

Mining scars—tailings, tramways, collapsed shafts—add industrial texture to natural desert backdrops, documenting how extraction economies reshaped arid environments you’re free to explore today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Ghost Town Sites Near Saguaro National Park Safe for Children?

Like desert mirages hiding real dangers, ghost town safety varies dramatically—managed sites offer controlled children exploration, but remote ruins near Saguaro harbor open shafts, rattlesnakes, and unstable structures requiring your constant vigilance and advance planning.

Can I Camp Overnight at Fairbank or Other Ghost Town Locations?

You can’t camp overnight at Fairbank—camping regulations require you’re half a mile from trailheads. Most Arizona ghost towns lack camping amenities; you’ll need nearby BLM dispersed sites or established campgrounds instead.

Do I Need a High-Clearance Vehicle for the Ghost Town Trail?

Yes—you’ll want a high-clearance vehicle. Trail conditions vary dramatically: washboarded segments, embedded rock, and deep ruts challenge standard cars. Most explorers choose SUVs or trucks to safely navigate this historic mining corridor’s rougher stretches.

Are There Guided Tours Available for Southern Arizona Ghost Towns?

Yes, you’ll find guided tour options throughout southern Arizona’s ghost towns, from Old Tucson’s lantern-lit walks to Tombstone’s trolley tours, each revealing the historical significance of Arizona’s mining-era boomtowns and forgotten settlements.

What Photography Equipment Works Best for Capturing Ghost Town Ruins?

You’ll want weather-sealed bodies with wide-angle lenses (14–35mm) for tight interiors and architectural detail. Master natural lighting techniques using portable LEDs in dark rooms, preserving the authentic character of these deteriorating desert settlements through careful lens selection.

References

- https://mwg.aaa.com/via/places-visit/arizona-ghost-towns

- https://www.experiencescottsdale.com/stories/post/ghost-towns-in-arizona/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q18D1sHH2Cc

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g28924-Activities-c47-t14-Arizona.html

- https://goldfieldghosttown.com

- https://www.freakyfoottours.com/us/arizona/

- https://azoffroad.net/golden-turkeygolden-belt-mines

- https://azgs.arizona.edu/minerals/mining-arizona

- https://thediggings.com/mines/6075

- https://www.mininghistoryassociation.org/PrescottMiningHistory.htm