Within 90 minutes of San Antonio, you’ll discover authentic ghost towns like Helena, once Karnes County’s seat until the railroad bypassed it in 1886, and Old D’Hanis, where stone ruins from Henri Castro’s 1847 Alsatian settlement still stand. Closer in, Berg’s Mill disappeared into suburban development, while Van Raub and Wetmore faded as rail-dependent economies collapsed. These sites preserve limestone buildings, active cemeteries with 1870s headstones, and historical markers that reveal how railroad routes and county politics determined which Texas settlements survived and which vanished into the mesquite-covered landscape awaiting your exploration.

Key Takeaways

- Helena, founded in 1852, lies 70 miles from San Antonio and features historical markers detailing the 1857 Cart War.

- Old D’Hanis, established in 1847, is located 50 miles away with preserved stone ruins and St. Dominic Catholic Church.

- Berg’s Mill once thrived along Mission Road after 1879 but vanished by the 1960s due to urban development.

- Van Raub, an 1884 railroad stop, was incorporated into Fair Oaks Ranch during the 1990s near San Antonio.

- Visit between November and March for optimal weather, bringing water and sun protection due to limited services.

Helena: The Former County Seat Frozen in Time

When Thomas Ruckman and Lewis S. Owings founded Helena in 1852 along the Chihuahua Road, they couldn’t foresee their trading post would become legendary as the “toughest town on earth.”

Serving as Karnes County’s first seat from 1854 to 1894, Helena thrived on stagecoach traffic, cattle drives, and rowdy commerce. The town’s saloons and gambling houses embodied frontier justice—violent, unregulated, and often deadly.

Helena’s saloons and gambling halls delivered swift, brutal justice where law was sparse and violence settled most disputes.

During the 1857 Cart War, ethnic tensions erupted into murders and vigilante hangings over freight competition. The town was notorious for the Helena Duel, where men tied at the wrist fought with knives while spectators wagered on the bloody outcome.

When the San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railway bypassed Helena in 1886, allegedly influenced by rancher W.G. Butler after his son’s killing there, the town’s fate was sealed.

The Karnes County Historical Society has worked since 1962 to preserve Helena’s legacy, relocating the original courthouse and post office to museum grounds alongside the Ruckman House and other historic structures.

Today you’ll find remnants of Helena history scattered across empty fields, a reflection of frontier excess.

Old D’Hanis and the Ruins of St. Dominic Catholic Church

As the fourth and final chapter of Henri Castro’s ambitious colonization project, Old D’Hanis emerged in 1847 when 29 Alsatian families settled along the San Antonio–Rio Grande Road in what would become Medina County.

Named for William D’Hanis, Castro’s colonization manager, the settlement thrived until the railroad bypassed it in 1881, spawning New D’Hanis 1½ miles west.

Old D’Hanis history centers on freedom-seeking Europeans who built stone homes and St. Dominic Catholic Church as their community’s heart. The settlers initially lived in mesquite shacks before constructing their permanent stone buildings. The community also endured a diphtheria epidemic during its early years.

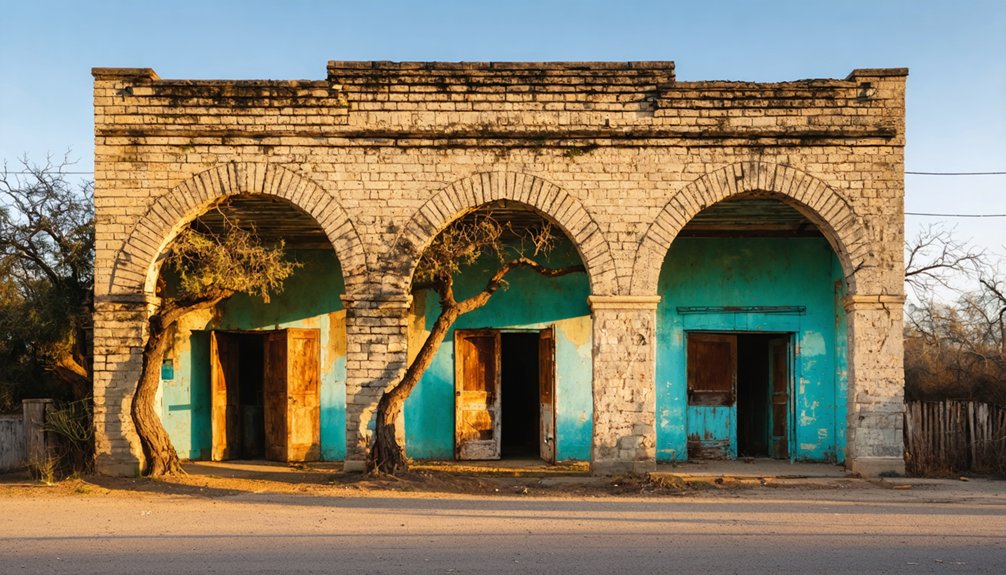

Today, the St. Dominic ruins stand as evidence of frontier perseverance—roofless stone walls and arches remain after an 1912 fire ended services.

You’ll find:

- Cemetery headstones marking 1847 deaths, including “Killed by Indians”

- European-style stone architecture amid mesquite and cacti

- National Register designation (1976)

- Original 20-acre farm plots still visible

Berg’s Mill: Swallowed by Metropolitan Growth

While Old D’Hanis dwindled when the railroad passed it by, Berg’s Mill met a different fate—absorbed entirely by the relentless sprawl of metropolitan San Antonio.

You’ll find its historical marker along Mission Road, where L.S. Berg’s 1879 grist mill once processed grain near Mission San Juan Capistrano. The settlement flourished after the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway arrived, earning a post office by 1887.

Stone ruins still stand east of Berg’s Mill bridge, silent witnesses to successive operators—Louis Ashley, the Berg brothers, Gustave Hellemans, and later owners who worked these grounds into the 1930s.

The weathered stones remain, marking each generation who ground grain here until the mills finally fell silent.

Urban development eventually swallowed what railroads had built, transforming agricultural mills into suburban neighborhoods, leaving only markers to remind you freedom once meant wide-open South Texas land. The community that once peaked at barely 100 residents by 1940 had vanished entirely from maps by the 1960s. The Texas State Historical Association continues preserving such stories through community contributions that fund ongoing historical documentation efforts.

Van Raub: A Fading Rural Settlement Northwest of the City

Twenty-four miles northwest of San Antonio, near where Cibolo Creek crosses beneath Interstate 10, you’ll find the vanished settlement of Van Raub—a community born from railroad ambition in 1884 and erased by suburban sprawl a century later.

The community evolution followed a familiar trajectory for Texas railroad towns:

- 1884-1885: Byron Van Raub established this San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad stop with church, school, cotton gin, and newspaper.

- 1910: Population peaked at 150 residents before economic decline began.

- 1912-1919: Cotton gin bankruptcy and post office closure stripped away economic foundations.

- 1990s: Fair Oaks Ranch incorporation absorbed the area entirely.

Van Raub’s historical significance lies in documenting how railroad dependency and agricultural economics shaped—then doomed—rural Texas settlements, transforming thriving communities into suburban developments. Like other Texas company towns of the era, Van Raub residents faced economic control through limited wage opportunities and company-dependent infrastructure. The town’s founder, originally Byron H. Robb, had changed his name after exposure as a fraud in Ohio during the 1880s before relocating to Texas.

Wetmore: Remnants of a Vanished Rail Community

Eleven miles northeast of downtown San Antonio, where the Houston and Great Northern Railroad carved through Bexar County in 1880, the settlement of Wetmore emerged as another indication of the era’s railroad fever.

Named after railroad director Jacob S. Wetmore, this community’s railroad legacy tied directly to the International-Great Northern line that promised prosperity to anyone willing to stake their future on iron rails and steam engines.

You’ll find little remaining of the town that opened its post office in 1890 and grew to fifty residents by 1920.

Economic decline followed as railroad dependence proved unsustainable. The tracks that once represented progress became monuments to miscalculation.

Today, Wetmore stands as evidence that proximity to San Antonio alone couldn’t guarantee survival when your entire existence depended on trains that eventually stopped coming.

The Texas Historical Association works to preserve state history like Wetmore’s through community contributions and historical records.

Nearby, adventurous explorers seeking treasure discovered man-made walls deep within Robber Baron Cave during the early twentieth century.

Luxello: Lost to Changing Transportation Routes

Eighteen miles northeast of downtown San Antonio, where the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad crossed Cibolo Creek around 1900, the settlement initially called Landa emerged as yet another community betting its future on rail access.

Renamed Luxello in 1915 after postmaster Charles Lux, this tiny hamlet of 35 residents thrived briefly around its station and general store.

Luxello’s railway transformation unfolded through:

- 1915–1920s: Peak rail service supporting local commerce and daily travel

- 1920s–1940s: Population stagnation at 25 as automobiles replaced trains

- Post-WWII: Suburban encroachment from expanding Selma and Universal City

- Late 1980s: Complete disappearance from maps, absorbed into anonymous sprawl

You won’t find Luxello on modern maps—highways bypassed it, suburbs swallowed it, and independent identity vanished.

Catarina: Oil Boom and Bust in Dimmit County

Along U.S. Highway 83 in southern Dimmit County, you’ll find Catarina’s remnants ten miles southeast of Asherton.

During the 1920s oil boom, developers transformed this depot settlement into a “County of Miracles” showcase, promising irrigated-farm riches. Charles Ladd imported fruit-laden citrus orchards to demonstrate instant productivity, while Catarina Farms built hotels, waterworks, and electric systems.

Population exploded to 2,500 by 1929.

The oil boom and promises of irrigated prosperity drew thousands to this remote South Texas settlement in less than a decade.

Yet freedom from conventional farming wisdom proved costly. Artesian wells failed by the late 1920s, forcing expensive pumping operations. Agricultural decline accelerated as water shortages merged with marketing problems and Depression-era collapse.

Population crashed to 592 by 1931.

Today, Catarina stands nearly abandoned—a stark reminder that speculative prosperity built on finite resources rarely endures.

Why Railroads and County Seats Decided These Towns’ Fates

While oil booms created spectacular cycles of growth and collapse, railroads wielded a quieter yet more decisive power over South Texas settlements—choosing which towns would thrive and which would fade into obscurity.

The railroad impact on community survival followed predictable patterns:

- Route selection determined winners – Helena lost its county seat to Karnes City after the San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railway built seven miles away, creating the “Big Curve” that redirected all commerce.

- County seat status amplified advantages – Courthouse locations brought lawyers, merchants, and steady traffic; losing that designation meant losing professional services and political relevance.

- Bypassed towns withered rapidly – Communities like Berg’s Mill and Wetmore saw stores, depots, and post offices close once rail traffic favored larger centers.

- Highway planning followed rails – Road construction mirrored existing railroad corridors, compounding disadvantages for non-rail settlements.

What You’ll Find When You Visit Today

When you arrive at San Antonio’s best-preserved ghost towns, you’ll encounter a mix of stabilized limestone buildings, weathered storefronts, and the occasional restored courthouse or church now serving as a heritage museum.

Most sites feature at least one active cemetery—often the most carefully maintained remnant—where gravestones from the 1870s through 1940s document the German, Polish, and Czech families who settled these communities.

Interpretive centers and historical markers at places like Helena and Welfare provide context about railroad bypasses, county-seat relocations, and the agricultural shifts that emptied these once-thriving townsite grids.

Preserved Historic Buildings

The ghost towns scattered within a few hours’ drive of San Antonio reward visitors with tangible remnants of Texas’s frontier and early settlement eras, from carefully restored 19th-century courthouses to crumbling military outposts frozen in time.

These sites offer unmediated encounters with the past, where historic preservation efforts have safeguarded structures of genuine architectural significance.

What awaits your exploration:

- Helena’s two-story courthouse anchors a preserved town square alongside the original post office and first Masonic lodge, maintained by dedicated museum organizations.

- Fort McKavett’s stone barracks and officers’ quarters stand as stabilized ruins across an intact parade ground, interpreting frontier military life.

- Boerne’s German-style storefronts retain 19th-century facades within a protected historic district.

- Scattered remnants from Van Raub to Berg’s Mill mark former community centers with remaining shells and foundations.

Active Cemetery Sites

Beyond the standing buildings and crumbling walls, ghost town cemeteries near San Antonio persist as living archives where families still gather for burials, maintenance work continues sporadically, and visitors encounter the most complete physical records of who actually populated these vanished communities.

You’ll find headstones inscribed in German, Czech, Spanish, and English—testaments to the immigrant ranchers, miners, and soldiers who settled central Texas. Handmade concrete markers stand beside weathered granite monuments, while iron plot fencing and decorative stone curbs reflect 19th-century burial traditions.

Cemetery preservation efforts vary dramatically: some sites maintain locked gates after vandalism incidents, while others remain open but overgrown. Historical markers occasionally identify occupations and military units, connecting individual graves directly to the region’s mining camps, frontier forts, and agricultural settlements.

Museums and Interpretive Centers

Interpretive facilities scattered across San Antonio’s ghost town circuit transform abandoned structures and archaeological sites into readable history, offering you tangible connections to the ranchers, miners, and soldiers who occupied these settlements.

Ghost town museums preserve authentic artifacts—rusted mining equipment, frontier law-enforcement tools, and personal belongings—while interpretive exhibits decode the economic forces that turned thriving communities into windswept ruins.

Key interpretive centers include:

- Bandera County Jail Museum – Original 1881 stone cells, gallows area, and sheriff’s quarters documenting frontier justice

- Terlingua mining ruins – On-site signage explaining quicksilver operations and company-town collapse

- Luckenbach General Store – Historic trading post displaying mailboxes, farm tools, and music-era memorabilia

- Fort McKavett State Historic Site – Military artifacts reconstructing cavalry-era garrison life on Texas borderlands

Planning Your South Texas Ghost Town Road Trip

You’ll want to plan your South Texas ghost town loop for late fall through early spring, when temperatures stay comfortable for exploring exposed ruins and walking through cemetery grounds.

The easiest one-day route runs southeast from San Antonio to Helena via US 181 (70 miles, 1–1.5 hours), then circles back through farm-to-market roads, while a western alternative takes you to D’Hanis along US 90 (50 miles, under an hour) with options to extend into Hill Country towns.

Pack plenty of water, sun protection, and a charged phone—many sites sit on unpaved roads with limited cell service, and heavy rain can make back routes temporarily impassable.

Best Routes and Timing

Planning an efficient ghost town road trip from San Antonio demands strategic route design that balances driving distance against site density and terrain challenges.

Route optimization begins with identifying county-level clusters—Wilson County’s 30+ sites and Bexar’s 10+ locations offer concentrated exploration opportunities that minimize windshield time.

Smart travel tips include:

- Daily mileage targets: Plan 150–250-mile loops covering 4–8 sites, accounting for slow farm-to-market roads and unpaved county routes that reduce average speeds to 45–55 mph.

- Seasonal timing: November through March delivers cooler temperatures and better visibility, avoiding brutal summer heat exceeding 100°F at exposed townsites.

- Loop strategies: The South & Southeast circuit via US-181 connects Panna Maria, Polish Triangle, and Karnes County relics in one day.

- Mapping tools: Leverage TexasEscapes and BatchGeo coordinates to pinpoint density hot spots before departure.

Essential Supplies and Safety

Because South Texas ghost towns sit dozens of miles from medical facilities and emergency services, preparation separates memorable exploration from dangerous misadventure.

You’ll need emergency preparedness basics: paper maps for counties with unreliable cell coverage, a fully charged phone with portable power bank, and navigation tools including offline GPS apps preloaded with rural routes.

Pack one gallon of water per person daily, electrolyte tablets, and high-calorie shelf-stable foods.

Inspect your vehicle’s tires, coolant, and AC before departure, carrying spare tire equipment and traction aids for caliche roads. Refuel at half-tank intervals in remote areas.

Bring a first-aid kit, closed-toe boots for snake country, dust masks for ruins exploration, and county appraisal maps to verify land ownership and avoid trespassing citations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are These Ghost Towns Safe to Visit Alone or at Night?

Want true freedom without unnecessary risk? You shouldn’t explore ghost towns alone at night—crumbling structures, wildlife, trespassing laws, and zero cell service make solo exploration dangerous. Follow safety tips: visit during daylight with companions.

Do I Need Permission to Explore Private Ghost Town Properties?

Yes, you’ll need permission. Property rights protect private ghost town land under Texas trespass law. Exploration ethics demand you contact owners, verify boundaries through county records, and respect “No Trespassing” signage before entering.

What Should I Bring When Visiting Remote Ghost Town Sites?

You’ll need hiking essentials like sturdy boots, ample water, sun protection, and navigation tools with offline maps. Pack camera gear with extra batteries, first-aid supplies, and emergency roadside equipment for unpaved backcountry routes beyond cell coverage.

Are There Guided Ghost Town Tours Available From San Antonio?

No major operators currently market dedicated guided excursions to nearby ghost towns from San Antonio. You’ll find urban haunted walking tours downtown instead, offering historical insights into the city’s paranormal sites, while outlying ghost towns require self-drive exploration.

Can I Metal Detect or Collect Artifacts at These Locations?

Metal detecting laws generally prohibit artifact collection at ghost town sites without landowner permission. You’ll face restrictions protecting artifact preservation on federal, state, and private lands. Always secure written authorization before detecting, and respect archaeological protection requirements.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.sanantoniothingstodo.com/texas-ghost-towns-san-antonio-tx/

- https://livefromthesouthside.com/10-texas-ghost-towns-to-visit/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ndTmBBAC1I

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/Texas-Ghost-Towns-8-South-Texas.htm

- https://www.county.org/county-magazine-articles/summer-2025/ghost-towns

- https://www.expressnews.com/lifestyle/article/ghost-towns-san-antonio-bexar-county-texas-18334364.php

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowTopic-g60956-i76-k13209414-Ghost_Towns_within_driving_distance_of_San_Antonio-San_Antonio_Texas.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RckOzWMCCXs

- https://westwardsagas.com/helena-the-toughest-town-on-earth/