You’ll discover more than a dozen authentic ghost towns along Nevada’s Highway 50, where boom-and-bust mining cycles left haunting remnants of frontier ambition. Berlin, founded after 1863 mineral discoveries, preserves its 30-stamp mill and miners’ cabins after processing $850,000 in ore before fires and depletion emptied it. Hamilton once housed 10,000 silver-seekers in White Pine County before collapsing within a decade. These settlements trace back to 1860s Pony Express stations, with over 50 relay points still visible today. The complete story reveals how railroad failures and transportation shifts transformed thriving communities into archaeological treasures.

Key Takeaways

- Route 50 ghost towns like Berlin and Hamilton emerged from 1860s mining booms but declined after ore depletion and devastating fires.

- Berlin preserves miners’ homes, assay offices, three miles of tunnels, a cemetery, and notable Ichthyosaur fossils as a historic site.

- Kansas towns like LeLoup and Bazaar thrived as railroad hubs but became ghost towns after railroad bankruptcies and automobile travel.

- Middlegate Station remains a functional stop featuring frontier memorabilia and the famous Monster Burger Challenge on the isolated highway.

- Ancient petroglyphs at Grimes Point and Hickison, over 10,000 years old, mark indigenous presence predating modern settlements along Route 50.

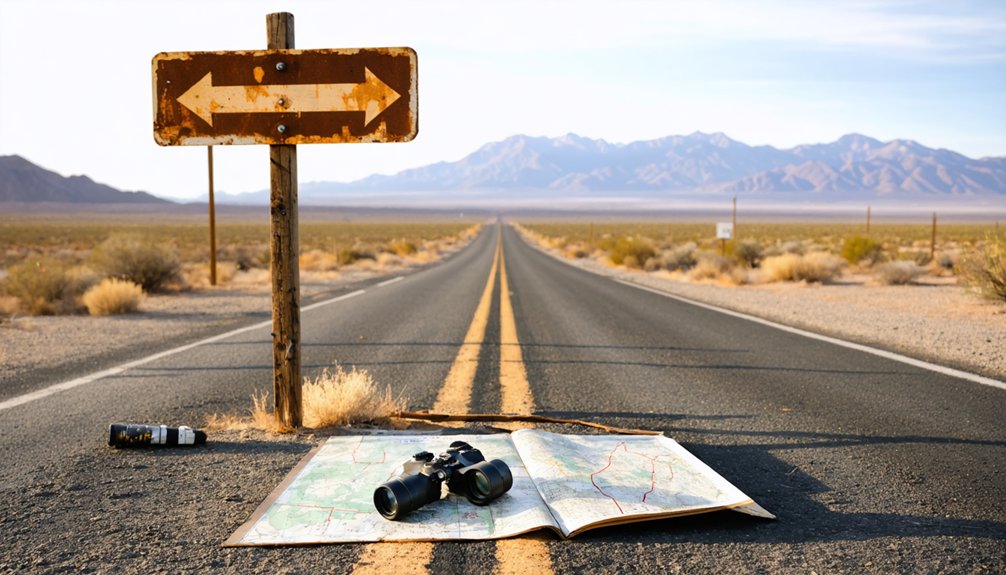

The Loneliest Road in America: Highway 50 Through Nevada

Long before Life magazine dubbed it “the Loneliest Road in America” in 1986, Highway 50’s Nevada corridor carried desperate prospectors, galloping Pony Express riders, and Union soldiers across what pioneers feared as the Forty Mile Desert—a waterless, heat-scorched stretch between the Carson and Humboldt rivers that marked the most dreaded segment of the California Trail.

You’ll traverse this same emptiness today, where sagebrush and desert flora replace civilization for 80-mile stretches. Nevada’s tourism commission cleverly reclaimed the designation, offering a Highway 50 Survival Guide requiring stamps from five sparse towns—Fernley, Fallon, Austin, Eureka, and Ely—to earn the governor’s certificate.

The route’s heritage stretches back to 1860 when the Pony Express mail service first blazed this trail across Nevada, enabling coast-to-coast communication in as little as 10 days. The highway crosses 17 mountain passes through vast valleys, following the path of old mining camps and stagecoach stations that once served as lifelines across the Great Basin. These roadside attractions punctuate genuine remoteness, where you’re free to experience America’s Great Basin exactly as those 1860 express riders did: unfiltered, unforgiving, and utterly alone.

Kansas Ghost Towns Along Historic US 50

As you trace the original alignment of U.S. 50 through Chase County, you’ll encounter LeLoup, a settlement whose French name—meaning “the wolf”—emerged from a documented incident involving a local wolf hunt that troubled early settlers in the 1860s.

The railroad’s arrival in the 1870s briefly sustained these prairie communities, but when the Santa Fe Railway bypassed Homewood in favor of other routes, the town’s population declined precipitously from its 1920s peak. Settlements along Route 50 were initially established to serve travelers on the Santa Fe Trail, which shaped early commerce and population patterns across the region. Nearby Bazaar peaked in 1921 with 100 residents and served as a key railroad cattle shipping point before experiencing similar decline.

Historical records and century-old cemetery markers at sites like St. John’s reveal how these communities thrived during the railroad era, only to fade as transportation corridors shifted and agricultural consolidation reduced the need for closely-spaced service towns.

LeLoup’s Notable Name Origin

Among the colorful naming stories scattered across Kansas’s frontier settlements, LeLoup stands out for its peculiar Franco-American origin. You’ll find two competing accounts explaining how Ferguson became LeLoup in 1879.

The first describes a French traveler mistaking a coyote for a wolf, shouting “Le Loup”—prompting residents to vote for renaming their railroad town. The alternative version credits French settlers who heard wolves howling nightly, exclaiming the same phrase.

Either way, the community embraced this exotic departure from founder Robert Ferguson’s surname. The post office officially adopted the name on May 8, 1879, cementing this linguistic oddity into the settlement origins of northeastern Franklin County. The town maintained its post office for approximately 84 years before eventual closure.

This Franco-American fusion reflected the diverse cultural influences shaping Kansas’s historical architecture and frontier identity. By the early 1880s, LeLoup had developed into an important shipping point for grain, hay, and stock, serving the agricultural community seven miles northeast of Ottawa.

Homewood’s Railroad Era Decline

You’ll notice three forces behind these economic shifts:

- Union Pacific’s October 1893 bankruptcy rippled through connected regional railways.

- Kansas recorded its first line abandonment in 1891, expanding to 202.5 miles by 1900.

- Federal highway subsidies post-1910 diverted freight and passengers to trucks and automobiles.

The St. Joseph and Grand Island Railway emerged from receivership in February 1897 as an independent company following the financial collapse.

The 1873 Panic triggered a depression that ultimately led over 40,000 miles of rail to fail by 1894, devastating railroad-dependent communities across the Great Plains.

Berlin: A Mining Town Frozen in Time

When prospectors stumbled upon silver in Union Canyon during May 1863, they couldn’t have envisioned that their discovery would spawn one of Nevada’s best-preserved ghost towns just over three decades later.

Berlin’s mining history began in earnest when the Nevada Company purchased claims in 1898, transforming the canyon into a bustling operation.

You’ll find remnants of its sophisticated 30-stamp mill, which processed $849,000 worth of ore through eight underground levels spanning three miles of tunnels.

The 1907 miners’ strike abruptly ended Berlin’s prosperity, but Nevada’s 1970 acquisition for Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park guaranteed exceptional town preservation.

Today, you can explore 30-plus structures frozen in arrested decay—from the assay office to miners’ homes—offering an authentic glimpse into turn-of-the-century mining life without commercialized reconstruction.

The town’s cemetery remains maintained and accessible, containing graves of early residents including Josephine Ascargorta, D. Manuel de Totorica, and Margaret L. Goldsworthy.

The park also protects North America’s most abundant Ichthyosaur fossil deposits, making it a dual treasure of paleontological and mining heritage designated as a Registered Natural Landmark.

Pony Express Stations and Early Settlements

As you trace Route 50 through Nevada’s desert, you’ll discover that many relay stations established during the Pony Express‘s 18-month operation evolved into permanent settlements along the Central Overland Route.

The strategic spacing of 186 stations every 10-15 miles created infrastructure that attracted ranchers, merchants, and stage operations after the telegraph ended the Express in October 1861. These rudimentary outposts—like Cold Springs, 50 miles west of Austin, and Sand Springs at Sand Mountain’s base—transformed isolated wilderness into a lifeline for westward expansion.

Approximately 50 stations are still visible today as ruins or restored structures.

Relay Stations Become Towns

Along the approximately 1,900-mile Pony Express route established in April 1860, relay stations spaced 10 to 15 miles apart served as the operational backbone that enabled riders to maintain their legendary 75-mile-per-run average speeds. These utilitarian outposts evolved beyond their original mail-carrying purpose, transforming into essential community hubs.

Route evolution demonstrates how infrastructure shapes settlement patterns:

- Five Mile House (Mills Station) functioned as Sacramento’s first eastward remount station, where Sam Hamilton changed horses on April 4, 1860.

- Sportsman’s Hall (Twelve-Mile House) operated as a relay station where Warren Upson received Hamilton’s mail at 7:40 a.m., departing two minutes later.

- Yank’s Station began as Martin Smith’s 1851 trading post before becoming California’s easternmost Central Overland station.

This Pony Express history reveals how temporary facilities catalyzed permanent western expansion.

Central Overland Route Connection

The Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company organized the Pony Express route into five distinct divisions spanning 1,900 miles from St. Joseph to Sacramento. Russell, Majors, and Waddell’s venture acquired 400-500 horses and hired 200 stationmasters to establish relay points every 10-15 miles along repaired roads bypassing Denver.

This ambitious postal history experiment launched in April 1860, promising ten-day mail delivery across territories where Native legends spoke of ancestral lands now bisected by emigrant trails. The route traced established pathways through Nebraska Territory, Wyoming’s Fort Laramie country, Utah’s Salt Lake Valley, and California’s Sierra Nevada.

Hamilton and the White Pine County Silver Rush

- A $55,000 brick courthouse signaling governmental permanence.

- A $400,000 water system designed for 50,000 residents.

- Multiple mills processing ore assaying $15,000 per ton.

Yet reality proved harsh. Ore bodies depleted by 1870, collapsing Hamilton’s population from 10,000 to 500 within three years. Fires in 1873 and 1885 erased what remained.

From 10,000 souls to 500 in three years—geological limits crushed Hamilton’s dreams faster than Nevada’s desert sun bleached its bones.

Today, Hamilton stands abandoned—a demonstration to unfettered ambition meeting geological limits on Nevada’s loneliest highway.

Middlegate Station and the Monster Burger Challenge

The restaurant ambiance—bull skulls, antique wagons, cash-plastered ceiling—preserves its frontier heritage while serving modern travelers.

Local cuisine reaches legendary status with the Monster Burger Challenge: you’ll face four pounds of food crowned by 1⅓ pounds of beef.

Complete it, and you’ll earn a commemorative t-shirt.

Stephen King recognized this station’s authenticity, spending seven days here writing *Desperation*.

It’s proof that Nevada’s frontier spirit thrives through evolution, not extinction.

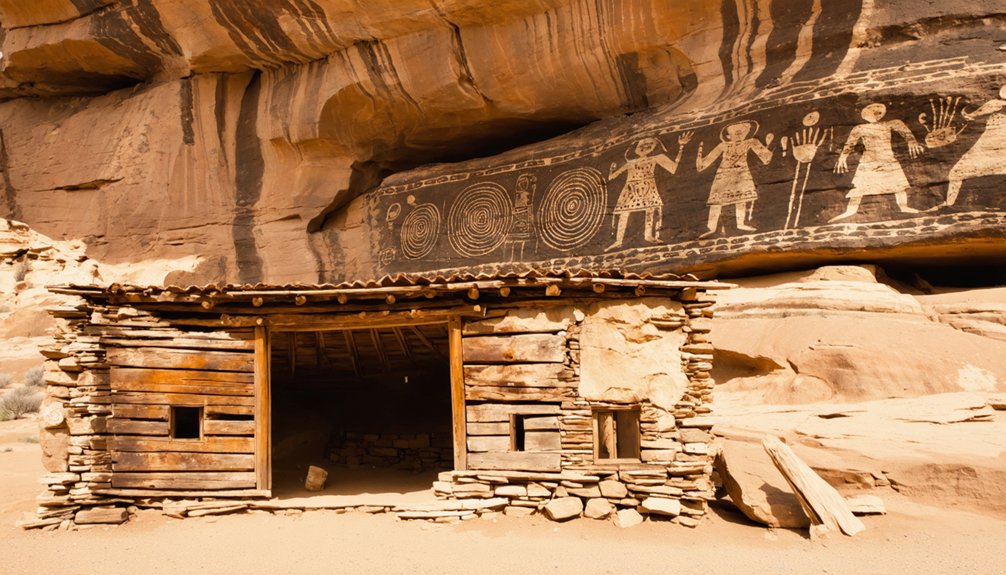

Ancient Petroglyphs and Archaeological Wonders

Along Highway 50’s desolate stretches, ancient voices speak through stone—carved messages from civilizations that thrived when today’s desert valleys cradled vast inland seas. Ancient petroglyphs at two remarkable sites reveal 10,000 years of human presence along this lonesome road.

Archaeological marvels await exploration:

- Grimes Point (10 miles from Fallon): You’ll find 8,000-year-old swirling designs on volcanic boulders, linked to hunting rituals when Lake Lahontan filled the basin.

- Hickison Petroglyph Recreation Area (24 miles east of Austin): Rock outcroppings display carvings from 10,000 BC, created during Lake Toiyabe’s existence.

- Western Shoshone Heritage: Both sites preserve seasonal movement patterns and wetland habitats.

Easy quarter-mile trails connect you with prehistoric hunters who understood freedom’s essential nature—following game, water, and seasons across this unforgiving landscape.

Why These Communities Became Ghost Towns

When precious metals ran out, entire civilizations collapsed almost overnight along Route 50’s corridor. You’ll find Ely, Eureka, and Austin—once-thriving boom towns—reduced to populations of just hundreds after resource exhaustion ended their mining heyday. Berlin stands preserved as a ghost town, its abandoned structures surrounded by ichthyosaur fossils that predate even Indigenous legends of the region.

The economic reality was brutal. These communities existed solely to extract wealth, unlike Ancient trade routes that sustained diverse commerce. When ore veins depleted, investors abandoned infrastructure immediately.

A mineshaft collapse near Ely in the late 1800s exemplifies this callousness—a foreman refused rescue efforts for ten trapped Asian workers due to costs. Their preserved corpses, discovered a century later, testify to an era when profit trumped human dignity, leaving desolate valleys where civilization once flourished.

Planning Your Ghost Town Road Trip

Before setting out across Nevada’s emptiest quarter, you’ll need meticulous preparation that matches the stakes faced by early Pony Express riders who traversed this same corridor. Stock camping essentials and water at every fuel stop—Middlegate Station marks your last reliable checkpoint before Ely’s 260-mile stretch. Cash remains essential since remote roadhouses can’t process digital payments.

Your route planning should include:

- Vehicle preparation: Dirt roads accessing Belmont Mill and Osceola demand appropriate clearance and spare supplies.

- Wildlife awareness: Desert ecosystems harbor local wildlife active during dawn and dusk hours.

- Elevation readiness: Connors Pass (7,729 feet) and multiple summits require engine performance consideration.

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park offers established camping facilities, while dispersed camping throughout BLM lands provides complete solitude for self-reliant travelers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Any Ghost Towns Along Route 50 Privately Owned or Restricted?

You’ll find private ownership issues at Osceola, where residents maintain homes, and Belmont Mill’s unregulated status creates uncertain access restrictions. However, Berlin-Ichthyosaur and Ward Charcoal Ovens remain publicly accessible through state park management systems.

What Photography Equipment Works Best for Capturing Abandoned Buildings?

You’d think historic camera options matter most, but they don’t—lighting techniques trump gear. You’ll need wide-angle lenses (16-35mm), sturdy tripods for bracketing exposures, and cameras handling high dynamic range to capture Route 50’s decaying freedom.

Can Visitors Stay Overnight in Any Route 50 Ghost Towns?

You can’t stay overnight in Route 50’s actual ghost towns due to preservation efforts protecting historic ruins. However, you’ll find authentic lodging nearby in Austin, Eureka, and Ely that respect these fragile sites while providing convenient access.

As twilight descends, the dark sky preserves near ghost towns, casting an enchanting atmosphere that invites exploration. The surrounding landscapes tell stories of a bygone era, where the whispers of history resonate among the remnants of abandoned structures. It’s a perfect setting for photographers and adventurers eager to capture the haunting beauty of these forgotten places.

Which Ghost Towns Have Reliable Cell Phone Service or Connectivity?

You’re out of luck—no Route 50 ghost towns offer reliable cell service coverage. T-Mobile provides connectivity hotspots only in larger towns like Ely, Austin, and Eureka, while abandoned settlements remain communication dead zones requiring complete offline preparation.

Are There Guided Tours Available for Route 50 Ghost Towns?

Yes, you’ll find several guided tours exploring Route 50’s ghost towns, from Jackson House Hotel’s weekend ghost tours featuring local legends to Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park’s historical preservation tours showcasing mining structures and underground tunnel systems through Afterlife Antiques.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hDJVlbTVs8

- https://travelnevada.com/road-trips/loneliest-road-in-america/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Route_50_in_Nevada

- https://visitusaparks.com/surviving-the-loneliest-road-in-america/

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.ocweekly.com/the-shoe-trees-forbidden-caves-and-ghost-towns-of-nevadas-highway-50-7260997/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/users/lonecourier/lists/hwy-50

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fegh_yRyorY

- https://www.hotelnevada.com/blog/the-history-of-highway-50-americas-loneliest-road

- https://loneliestroad.us/history/