Arizona’s ghost towns offer you visible evidence of nature’s persistent reclamation, where mesquite roots split adobe walls and desert winds erode wooden structures at documented rates. You’ll find Charleston’s ruins vanished within three years, while Gleeson’s 1910 concrete jail endures as surrounding buildings deteriorate. Native flora destabilizes foundations at sites like Stanton and Kentucky Camp, creating dynamic landscapes where human settlement yields to environmental forces. Preservation efforts at Vulture City and Fairbank now balance this ongoing transformation with heritage tourism initiatives that reveal deeper patterns of abandonment.

Key Takeaways

- Adobe structures collapse fastest from wind erosion and flash floods, with Charleston’s ruins vanishing within three years of abandonment.

- Mesquite trees with deep taproots destabilize weakened walls, while native desert flora accelerates the disappearance of isolated ghost town structures.

- Wooden buildings like Ruby’s store deteriorate into lumber piles, while concrete structures like Gleeson’s jail endure longer in arid conditions.

- Sites like Kentucky Camp and Stanton demonstrate desert plants integrating with weathered buildings, with recovery influenced by soil and water availability.

- Agua Caliente’s spring-fed oasis attracts wildlife, while Swansea’s structures collapse along weathered dirt roads as nature reclaims abandoned settlements.

The Rise and Fall of Arizona’s Mining Boomtowns

When the United States acquired Arizona territory through the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, few could have predicted that beneath its desert mountains lay mineral wealth that would transform the landscape within a generation.

You’ll find that gold discoveries near the Colorado River during the 1860s sparked Arizona’s mining heritage, with Rich Hill yielding over 110,000 ounces. The economic impacts intensified as silver deposits around Tombstone attracted thousands after 1877.

However, the 1893 repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act devastated silver prices, forcing miners toward gold prospecting. By 1900, attention shifted to copper, and former boomtowns emptied as workers followed new opportunities. The Clifton-Morenci area, where initial claims were staked in 1872, represents one of the few districts where mining operations have continued to the present day.

The collapse of commodity prices in 1930 briefly revived interest in gold mining, bringing temporary life back to some abandoned camps before base metal mining regained dominance.

This cycle of discovery, exploitation, and abandonment created the ghost towns you’ll encounter today across Arizona’s backcountry.

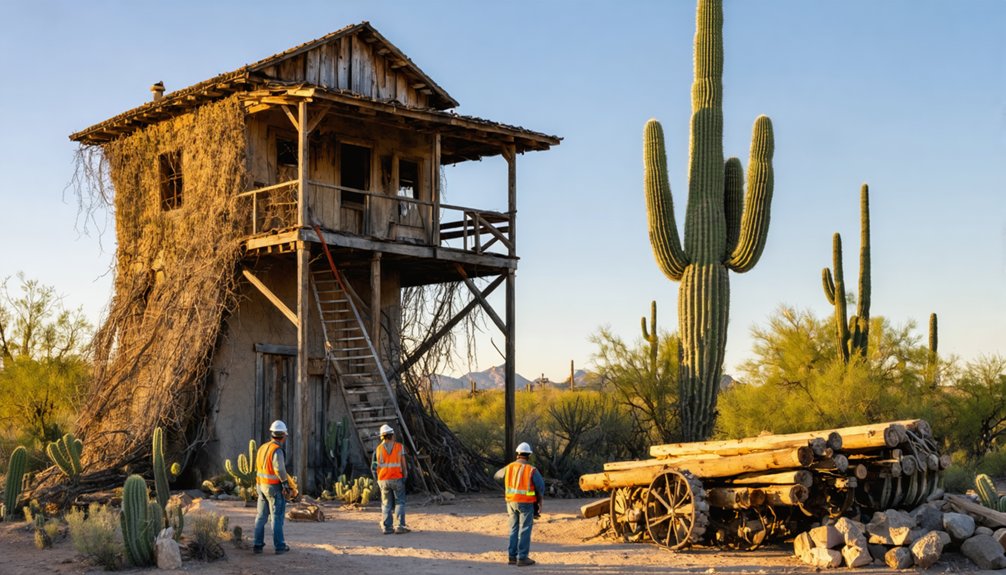

Desert Ruins: Where Crumbling Structures Meet Wild Overgrowth

The abandoned mining infrastructure that remains from Arizona’s boomtown era now exists in a dynamic relationship with the desert environment.

You’ll find nature’s encroachment transforming sites like Bisbee’s Galena stockpile, where vegetation claimed slopes in 2012. Urban decay manifests differently here than in wetter climates—with less than 10 inches annual rainfall, deterioration progresses through wind erosion and sporadic storms rather than lush overgrowth.

At Swansea, restored roofs protect single-men’s quarters along interpretive trails, while Stanton’s few original buildings stand with shored walls awaiting further preservation.

Jerome’s brick walls and slag piles mark the Main Street smelter site, now under EPA Superfund study. At Courtland, visitors must exercise caution due to open mining shafts scattered throughout the townsite. These landscapes reveal how desert reclamation operates: juniper and oak colonize north-facing slopes, establishing wildlife habitat amid mining remnants. Researchers can access historical documentation through multipage TIFF format archives, which preserve detailed records of these sites for ongoing environmental assessment.

Five Ghost Towns Vanishing Into the Landscape

Arizona’s most vulnerable ghost towns now dissolve into the landscape at accelerated rates, their trajectories documented through archival photographs and field surveys conducted by preservation organizations.

You’ll find ghostly legends and forgotten histories merging with mesquite and creosote as adobe walls surrender to wind erosion and flash floods.

These sites demonstrate nature’s reclamation patterns:

- Swansea’s sun-baked structures collapse incrementally along weathered dirt roads

- Agua Caliente’s spring-fed oasis attracts wildlife while walls crumble into foundation lines

- Courtland’s mining infrastructure rusts into unrecognizable forms across windswept terrain

Canyon Diablo and Dos Cabezas represent opposite trajectories—complete abandonment versus minimal human presence.

Each location offers unmediated access to historical decay, where you can witness architectural dissolution without interpretive barriers or regulated pathways.

Ruby’s remote location near the Mexican border has accelerated its deterioration, with more than two dozen structures including a jailhouse and schoolhouse gradually succumbing to the elements.

At Charleston, mesquite trees grow through the foundations of former buildings, demonstrating how the San Pedro River corridor’s vegetation aggressively reclaims abandoned settlements.

Adobe Walls and Weathered Wood: How Nature Reclaims Abandoned Settlements

When you examine Arizona’s ghost towns, you’ll notice adobe walls cracking from root intrusion while wooden frames enter arrested decay in the arid climate.

At sites like Harshaw, lost tin roofs expose brick residences to erosion, whereas Vulture Mine’s wooden structures demonstrate how desert conditions slow deterioration compared to humid environments.

This preservation paradox creates a laboratory where you can observe how moisture cycles, livestock impact, and vegetation reclaim human settlements at varying rates across the Sonoran landscape.

The recovery timeline depends on soil type and water accessibility, with coarse soil areas potentially seeing vegetation recovery within five years while fine-textured soils show minimal growth.

Preservation efforts at locations like Vulture City have utilized original materials from reconstructed buildings to maintain historical accuracy while protecting structures from complete natural reclamation.

Crumbling Structures Overtaken

Across Arizona’s abandoned settlements, nature wages a methodical war against human construction, with adobe and wood surrendering at vastly different rates to the desert’s harsh reclamation process.

You’ll find abandoned architecture deteriorating through distinct patterns:

- Adobe structures collapse fastest—Charleston’s ruins vanished within three years after 1886 flooding, while Harshaw’s dwellings crumble under sporadic storms in areas receiving under 10 inches annual rainfall.

- Wooden buildings succumb to desert elements—Ruby’s Clarke store became lumber piles by the 1970s, and Vulture City’s 1863-1942 structures disappear beneath shifting sands.

- Concrete and stone endure—Courtland’s jail stands prominently while wooden stores collapse nearby, demonstrating nature’s reclamation favors certain materials. Gleeson’s jail built in 1910 maintains its original structure while nearby wooden buildings have long since deteriorated. In modern Arizona communities like Casa Grande, entire subdivisions remain unsold as neighborhoods become dotted with abandoned construction projects showing early signs of nature’s encroachment.

This selective destruction creates an unintentional preservation hierarchy, where mining-era concrete foundations outlast the wooden structures they once supported.

Desert Flora Takes Hold

The desert’s patient invasion transforms Arizona’s ghost towns through a strategic deployment of native vegetation that exploits every structural weakness.

You’ll find mesquite trees threading roots through Vulture City’s crumbling adobe, while desert scrub engulfs Courtland’s scattered foundations. Flora encroachment accelerates where isolation prevents human intervention—Charleston’s ruins disappear beneath brush, and Ruby’s buildings yield to advancing shrubs despite their sturdy construction.

Desert adaptation gives native plants distinct advantages in reclaiming these settlements. Mesquite’s deep taproots destabilize weakened walls, while desert flora integrates seamlessly with weathered wood at sites like Kentucky Camp and Stanton.

You’ll witness this process along the Ghost Town Trail, where Gleeson, Courtland, and Pearce demonstrate nature’s systematic dismantling of human ambition. The desert reclaims what you once borrowed.

Fighting Back: Preservation Efforts Across Arizona’s Ghost Towns

While many ghost towns across Arizona crumble into dust, a dedicated coalition of preservationists has mounted an aggressive defense against time’s relentless erosion.

You’ll find ghost town preservation transforming abandoned settlements into accessible heritage tourism destinations. The Bureau of Land Management‘s stabilization of Fairbank’s adobe mercantile and Swansea’s interpretive trails exemplifies public stewardship.

Private efforts shine at Vulture City, where sixteen 1800s structures welcome seasonal visitors, and Stanton, where the Lost Dutchman’s Mining Association added infrastructure while maintaining authenticity.

Three preservation approaches sustaining Arizona’s mining legacy:

- Government management – BLM oversees Fairbank and Swansea with structural reinforcement

- Private restoration – Vulture City’s 2017 revival preserves original buildings

- Nonprofit intervention – Arizona Land Project secures Courtland’s remaining foundations

You’re witnessing history salvaged from desert reclamation.

From Ruins to Renewal: Ghost Towns Finding New Life

You’ll witness Arizona’s ghost towns evolving through three distinct pathways of renewal, where deteriorating structures gain economic purpose without sacrificing historical integrity.

Communities like Oatman and Chloride demonstrate how adaptive reuse transforms abandoned mining camps into viable destinations, while preservation initiatives at Ruby and Vulture City prioritize architectural restoration over commercial spectacle.

These transformations reveal how human intervention intersects with natural landscapes—from the Forest Service maintaining Kentucky Camp’s mountain setting to the Bureau of Land Management protecting Swansea’s desert structures—creating sustainable models that balance tourism revenue with ecological and cultural stewardship.

Historic Preservation Success Stories

Across Arizona’s desert landscape, abandoned mining settlements that once faced certain decay now stand as evidence of dedicated preservation efforts that have transformed crumbling ruins into accessible windows on the past.

You’ll find mining heritage authentically maintained through meticulous restoration work that honors original construction methods and materials.

Historic preservation has revived several significant sites:

- Vulture City – Rescued in 2017 using archival photographs, restoring structures from a mine that yielded $200 million in today’s gold values.

- Castle Dome – Converted 1970s abandonment into living museum with 50+ buildings and authentic artifacts.

- Goldfield – Completely rebuilt from foundations by dedicated preservationists hauling period-correct equipment across the Southwest.

These successes demonstrate how human intervention can capture fleeting moments before nature reclaims what remains.

Modern Tourism and Commerce

Preservation efforts that saved Arizona’s ghost towns from complete ruin have created unexpected economic engines across the state’s remote desert regions.

You’ll find heritage tourism driving substantial revenue, with La Paz County generating up to $216 million in travel spending—rebounding 6.7% after the 2009 downturn. Ghost town preservation transformed abandoned sites like Castle Dome’s mines into museums and Courtland’s structures into public attractions.

These destinations draw you alongside 300,000 annual visitors exploring Jerome and other historic settlements. In Cochise County, 74% of travelers actively participated in Old West experiences, rating their interest at 3.9.

Word-of-mouth accounts for 50% of visitor awareness, while authentic offerings like Jackie Boyz Little Italy restaurant demonstrate how commerce adapts within preserved historic frameworks, sustaining communities worldwide visitors now discover.

Sustainable Development Initiatives

While preservation rescued Arizona’s ghost towns from physical collapse, sustainable development initiatives now transform these sites into economically viable communities through targeted environmental remediation.

You’ll find programs like Superior’s EPA-funded “clean and lien” initiative addressing contaminated properties, creating shovel-ready sites for eco-friendly tourism ventures. The SEAGO Brownfields Program extends this approach across Clifton, Nogales, and mining-dependent communities through 2027.

These initiatives prioritize sustainable architecture principles:

- Infill development utilizing existing infrastructure rather than sprawl

- Revenue-generating properties that protect public health while attracting investment

- Historic building restoration for adaptive reuse and employment creation

From Agua Caliente’s hot springs to Kentucky Camp’s Forest Service cabins, you’re witnessing environmental stewardship replace extractive industries—transforming mining-era ruins into diversified economic opportunities that honor natural resources without exploiting them.

Environmental Restoration and Mine Reclamation Projects

Arizona’s landscape bears the physical imprint of more than a century of mineral extraction, with field surveys documenting mines across the state’s 72.9 million acres and creating an evolving archive of human impact on the desert terrain.

You’ll find the Mined Land Reclamation Program addressing environmental impact through restoration techniques that’ve transformed over 250 sites since 2007.

Freeport-McMoRan’s reclamation of 37 historic locations removed 227,000 cubic yards of waste rock while restoring 50 acres to native conditions.

Voluntary initiatives now span 1,100 acres, with advanced lidar and aerial imagery enabling precise monitoring of remediation progress.

The state maintains 100% inspection rates across 715 regulated operations, ensuring financial assurance mechanisms protect against future abandonment while systematically closing sites that previous generations left behind.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Arizona’s Ghost Towns Safe to Visit on Your Own?

Walking a tightrope between adventure and danger, you’ll find solo exploration risky without proper safety precautions. Verify land ownership, avoid unstable structures, and respect nature’s reclamation—trespassing and structural collapse threaten your freedom.

What Should I Bring When Exploring Ghost Towns in the Desert?

You’ll need exploration essentials like navigation tools, high-clearance vehicles, and first aid supplies. Desert safety requires abundant water, sun protection, sturdy boots, and emergency communication devices since you’re venturing into isolated, potentially hazardous terrain independently.

Can You Legally Remove Artifacts or Souvenirs From Ghost Town Sites?

No, you can’t legally remove artifacts from ghost town sites. Legal regulations protect archaeological resources on public lands, and artifact preservation requires items remain in their original context. Violations carry significant fines and potential imprisonment.

Which Ghost Towns Are Best for Photography and When Should I Visit?

You’ll find the best photography spots at Ruby’s dawn-lit ruins and Vulture City’s restored facades during golden hour. Ideal visiting times span October through April, when cooler temperatures let you explore nature’s gradual reclamation without summer’s oppressive heat.

Do Any Ghost Towns Offer Overnight Camping or Accommodations Nearby?

You’ll find camping options at Kentucky Camp ($75/night cabins) and Goldfield Ghost Town ($30-50/night), while nearby lodgings exist near Jerome. These preserved sites let you experience Arizona’s wilderness heritage on your own terms.

References

- https://mossandfog.com/abandoned-to-adored-creative-reuse-in-arizonas-forgotten-properties/

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/article/arizona-ghost-towns

- https://takingthekids.com/explore-abandoned-arizona-ghost-towns-with-an-eerie-kind-of-beauty/

- https://www.blm.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/AML_PUB_DecadeProgress.pdf

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/itineraries/these-8-arizona-ghost-towns-will-transport-you-to-the-wild-west

- https://webapp-new.itlab.stanford.edu/abandoned-towns-in-arizona

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2017-01/documents/navajo_nation_aum_screening_assess_report_atlas_geospatial_data-2007-08.pdf

- https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/1/1/11.3.25_TNC_Mining_the_Sun_Report.pdf

- https://winfirst.wixsite.com/arizonamininghistory/history

- https://westernmininghistory.com/library/37945/page1/