Delaware’s abandoned industrial sites reveal nature’s relentless reclamation of human enterprise. You’ll find over 15 mill ruins near Millsboro disappearing beneath vegetation, while Garrett Snuff Mill’s 14 buildings in Yorklyn succumb to overgrowth. Fort DuPont, once hosting 300 WWII structures, now retains just 65 deteriorating buildings as forests consume parade grounds and fortifications. Vanished settlements like Andrewsville and Old Furnace exist only in historical records, their foundations buried under thick woodland. These forgotten places demonstrate how wilderness aggressively erases industrial heritage, transforming manufacturing centers into wildlife habitats where scattered foundations mark displaced communities’ former existence.

Key Takeaways

- Garrett Snuff Mill’s 14 buildings in Yorklyn succumb to overgrowth, demonstrating nature’s power to reclaim abandoned industrial sites.

- Over 15 mill remnants near Millsboro blend into natural surroundings as vegetation aggressively consumes Delaware’s forgotten industrial places.

- Fort DuPont’s wooden barracks and military structures deteriorate under vegetation after 1945 decommissioning, with only 65 buildings surviving.

- Andrewsville and Old Furnace vanished mid-1800s, now reclaimed by forests with few traces of their colonial settlements remaining.

- DuPont Powder Mills, abandoned in 1921 after 288 explosions, transforms into wildlife habitat as nature overtakes former industrial grounds.

From Thriving Industries to Abandoned Foundations

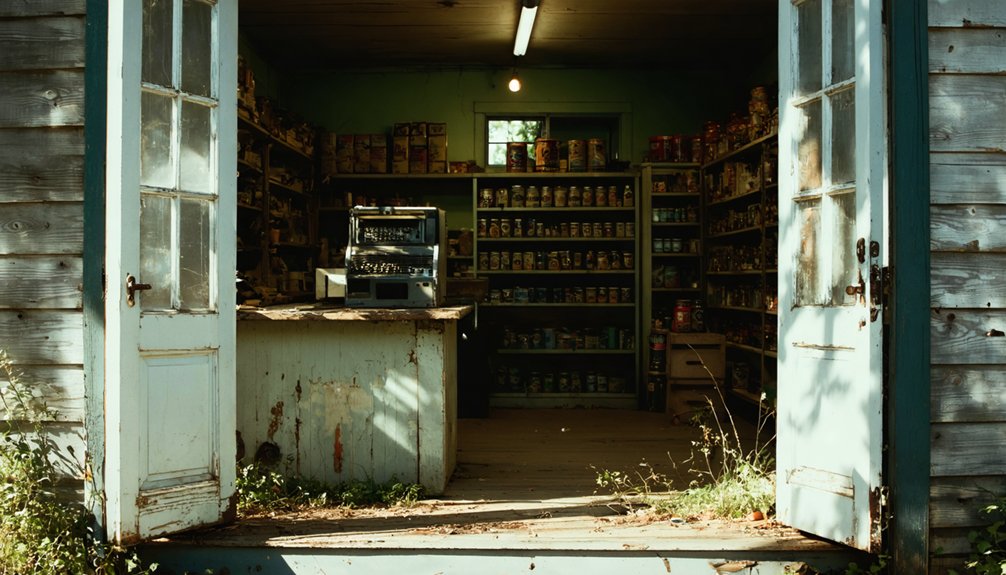

Along Delaware’s waterways, the skeletal remains of industrial complexes tell a story of economic transformation and ecological reclamation.

You’ll find Bancroft Mills, once the world’s premier cotton finishing factory in the 1930s, now crumbling into the Brandywine. The DuPont Powder Mills, which suffered 288 explosions killing 228 workers before abandonment in 1921, stand as monuments to dangerous enterprise.

Garrett Snuff Mill’s 14 buildings decay among overgrowth in Yorklyn. This industrial heritage reveals how quickly nature reclaims what humans build. Abbotts Mill, operating from the early 1800s until the early 1900s southwest of Milford, has been preserved as part of a state nature center since its addition to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. At the headwaters of the Indian River near Millsboro, remnants of over 15 mills that once operated within a 4-mile radius in the early 19th century blend into the natural surroundings.

Nature’s patient conquest of Garrett Snuff Mill proves that human industry, however mighty, remains merely temporary against ecological persistence.

Urban decay here isn’t merely aesthetic—it’s Delaware’s industrial backbone returning to earth. The ivy-covered ruins, fire-damaged walls, and collapsed structures demonstrate that your freedom from obsolete systems comes with visible consequences: abandoned foundations slowly disappearing into forests and riverbanks.

Fort DuPont: A Military Complex Lost to Time

If you walk through Fort DuPont today, you’ll encounter the physical evidence of sequential abandonment—from its decommissioning in 1945 through its transformation into the Governor Walter W. Bacon Health Center in 1948, using the very structures that once housed coastal artillery soldiers.

The site’s dramatic deterioration becomes apparent when you consider that approximately 300 buildings stood here during World War II, yet only 65 survived transfer to state ownership in 1946.

What remains now reflects a landscape caught between preservation and decay, where intact brick officers’ quarters exist alongside rotting wooden barracks, documenting how military infrastructure dissolves when strategic purpose disappears. Among the surviving structures, the Commanding Officers Quarters, constructed in 1910, stands as a testament to the fort’s hierarchical military past. The fort’s ten-gun battery, constructed between 1863 and 1864, represents the earliest physical remnant of this military installation’s transformation from Civil War-era earthworks to abandoned twentieth-century infrastructure.

World War II Healthcare Center

When Fort DuPont transformed from a coastal defense installation to a major World War II mobilization center, its military infrastructure took on urgent new purposes that would ultimately reshape its legacy.

You’ll find the 1909 Engineers’ Barracks became the foundation for military healthcare expansion, with a Medical Center constructed between 1906 and 1922 serving both garrison troops and an unexpected population.

By May 1944, temporary wooden structures housed 3,000 German POWs, including U-858 submarine crew members. Their POW experiences within these hastily constructed barracks represented a strange intersection of captivity and medical necessity.

When the state acquired 65 buildings in 1946, that same three-story brick barracks transformed into Governor Bacon Health Center, treating disturbed adolescents and adults requiring intermediate care until 1984. The state had purchased the site at a 100% discount from the federal government for its healthcare reuse.

The facility operated dual treatment units until the adolescent unit closure in 1984, after which the adult unit continued under the Department of Public Health’s supervision from 1987 onward.

Dramatic Decline of Structures

From its 1945 peak of 300 buildings, Fort DuPont’s architectural landscape began an irreversible collapse that would erase nearly all evidence of its eight-decade military presence.

When you walk through today’s remnants, you’ll find only 65 structures survived the initial 1946 transfer to Delaware. The forgotten history accelerated through decades of abandonment—officers’ quarters crumbled, batteries deteriorated, and masonry fortifications surrendered to vegetation.

By the time preservation efforts emerged, urban decay had claimed the parade ground, headquarters complex, and most Endicott-era emplacements you’d expect from a once-critical coastal defense installation. The site’s transformation from prisoner of war camp housing 3,000 POWs during World War II to abandoned ruins occurred with stunning rapidity.

Nature reclaimed what bureaucracy abandoned, transforming this sprawling military command into scattered foundations and overgrown concrete—a cautionary tale of institutional memory lost to time’s relentless advance.

Current State and Remnants

Though established as the Ten Gun Battery during the Civil War to protect Fort Delaware, Fort DuPont’s present landscape reveals only fragments of its transformation into a fully commissioned coastal defense installation in 1898.

You’ll find permanent brick buildings from the 1930s standing amid deteriorating fortifications history that spans multiple construction periods. The parade ground‘s commemorative flagpole marks where military ceremonies once unified the complex.

Officers’ quarters demonstrate remarkable architectural salvage—floated across from Fort Mott, New Jersey—while the theater incorporates bricks from Lord Fairfax’s 1736 Virginia mansion.

The Endicott-era gun pits and 1876 mine control casemates persist as concrete evidence of layered defense systems. The complex’s main armament, including the “Abbot Quad” with its sixteen 12-inch coastal defense mortars distributed across four gun pits, never engaged enemy forces and was deemed obsolete before World War II.

Today, Delaware’s Surplus Services Store and National Guard occupy repurposed quartermaster buildings, yet hastily constructed World War II structures have vanished completely.

When Vines and Nettles Bury History

Nature doesn’t simply reclaim Delaware’s forgotten places—it devours them with aggressive precision.

Five feet of stinging nettles and strangling vines buried Crowninshield Garden Ruins until crews executed controlled burns in 2019, revealing tunnels transformed into grottoes and foundations into pools.

Fort DuPont’s 300 buildings dwindled to fewer than 80 structures by 2011, overtaken by relentless vegetation that obscures entire streets.

Gibraltar Mansion’s terraces vanish beneath verdant overgrowth, while coastal woods consume Fenwick Lighthouse’s 1858 foundations.

Old Furnace’s remnants hide beneath regional flora along Deep Creek.

The site’s restoration has introduced new wildlife habitats where powder mill machinery once stood, transforming industrial devastation into ecological sanctuary.

Families displaced by dam construction return to find only scattered rocks and barn foundations beneath the encroaching wilderness, their homesteads now archaeological puzzles requiring careful excavation to locate.

This nature’s reclamation creates both beauty and erasure—you’ll find hidden histories entombed beneath bark and bramble, inaccessible until someone decides liberation matters more than wilderness.

Vanished Settlements Across Kent and Sussex Counties

You’ll find Kent and Sussex Counties harbor settlements that vanished so completely, even their founding dates blur into archival uncertainty.

In similar fashion, the vanished fishing towns in New England bear witness to the shifting tides of industry and culture. Once bustling with activity, these maritime communities now echo with memories of a bygone era, where life revolved around the sea. Each ghostly harbor tells a story of resilience and change, leaving behind only whispers of their past.

Andrewsville exists only as a name in scattered records, leaving no physical trace for you to examine, while Old Furnace five miles northeast of Deep Creek’s SH 46 crossing retains just enough geographic specificity to mark where iron manufacturing once sustained a community.

The forest has reclaimed both sites, transforming industrial landscapes back into the wilderness that preceded them.

Andrewsville’s Mysterious Disappearance

When Andrewsville vanished from Kent County’s landscape sometime in the mid-1800s, it left behind only scattered references on historical maps and fragments of pottery beneath the soil.

You’ll find few traces of this colonial settlement today—nature’s reclaimed what farmers once cultivated through backbreaking labor.

The Andrewsville history reveals a pattern you’d recognize across Delaware’s vanished communities:

- Poor soil conditions doomed colonial agriculture efforts despite settlers’ determination

- Migration toward industrializing cities drained populations from isolated rural outposts

- Lack of rail access sealed the town’s fate while neighboring settlements thrived

Now deciduous forests blanket foundations where families once pursued independent livelihoods.

The settlement’s disappearance wasn’t dramatic—just gradual abandonment as residents sought better opportunities elsewhere, leaving their agricultural dreams to forest overgrowth and wildlife.

Old Furnace Settlement Ruins

Three miles east of Seaford, the Old Furnace settlement tells a different story of abandonment—one driven not by agricultural failure but by industrial obsolescence. From 1750 to 1799, this iron furnace complex thrived alongside grist and lumber mills near Old Forge stream.

You’ll find its bloomery furnace remnants submerged underwater, preserved for over two centuries beneath accumulated mud and forest debris.

The industrial relics reveal themselves sporadically—slag heaps, charcoal deposits, foundation outlines emerging from plowed fields.

Thick stands of pine, sassafras, and bald cypress now reclaim what was once a bustling manufacturing center. The site’s shift from industry to farmland exposed scattered bricks and debris, evidence of Delaware’s early ironworking heritage slowly disappearing into Sussex County’s woods, rarely disturbed by human presence.

Maritime Relics Along Delaware’s Coastline

Long before Fort Miles stood sentinel over Cape Henlopen’s strategic waters, Native American communities left their mark through shell middens—ancient refuge heaps that reveal a thousand-year relationship with Delaware’s coastal resources.

These massive deposits, some measuring 90 feet long and 6 feet deep, span 1,000 to 1,600 AD beneath marshes and relict dunes.

Delaware’s maritime heritage persists through multiple eras:

- Fort Miles’ WWII artillery batteries now crumble within state parkland, their once-vital defenses rendered obsolete by missile technology

- Bowers Beach Maritime Museum preserves watermen’s artifacts from vanishing coastal traditions

- New Castle’s seven ice piers (1803-1880) stand as industrial maritime skeletons along the waterfront

Coastal preservation efforts struggle against nature’s relentless reclamation, as centuries of human endeavor dissolve back into sand and sea.

The Crowninshield Garden: Beauty Rising From Industrial Ruins

While Delaware’s coastline surrenders its human infrastructure to Atlantic tides, inland along the Brandywine River stands a paradox: deliberate ruins built atop accidental ones.

Louise du Pont Crowninshield transformed her family’s demolished black powder mill—where 228 workers died across 288 explosions between 1802 and 1921—into an Italianate fantasy garden.

She deliberately aged her neoclassical colonnades and terraces using chains and chisels, layering fabricated decay over authentic industrial tragedy. Mill tunnels became grottoes, refining kettles turned into planters, and blast foundations morphed into reflecting pools.

This garden aesthetics approach created what archivists call “a ruin within a ruin with a ruin.”

You’ll find no similar landscape worldwide—where industrial heritage and romantic escapism merge so completely that nature reclaims both the catastrophic past and its carefully orchestrated memorial simultaneously.

Communities Displaced and Forgotten

Before Delaware’s beaches claimed vacation cottages or industry claimed mill workers, violence claimed Zwaanendael—the state’s first European settlement and first ghost town. Within one year of its 1631 founding, conflict with the chief’s followers ended in massacre, every settler killed.

Delaware’s first European dream lasted exactly one year before violence erased every settler from Zwaanendael in 1632.

This pattern of displacement echoes through Delaware’s landscape:

- Native conflicts erased entire communities before colonial maps dried

- Industrial collapse abandoned manufacturing towns like Bancroft Mills after 174 years of operation

- Natural disasters forced government buyouts in Glenville by 2004, homes bearing desperate sale pleas

Each abandonment reveals something about community resilience—or its limits.

These sites carry historical significance beyond architecture, marking where human ambition met immovable forces. Nature doesn’t care about your property lines or industrial legacies. It simply reclaims what was always borrowed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Delaware’s Ghost Towns Safe to Visit and Explore Today?

Delaware’s ghost town safety varies dramatically—you’ll face exploration risks from unstable structures, restricted access on private land, and environmental hazards. While some sites like Fort Delaware offer regulated visits, you’re risking trespass and injury at abandoned locations.

What Wildlife Species Now Inhabit Delaware’s Abandoned Ghost Town Areas?

You’ll find limited documentation exists, but wildlife resurgence in Delaware’s sparse abandoned areas typically mirrors statewide patterns—deer, foxes, and songbirds reclaiming spaces where human activity ceased, demonstrating nature’s persistent ecological restoration despite archival gaps.

Can the Public Access Fort Dupont’s Remaining Historic Buildings?

You’ll find public access to Fort DuPont’s grounds and exteriors, though historic preservation efforts limit interior building entry. The redevelopment balances heritage conservation with community revival, letting you explore pathways while protecting structural integrity during ongoing restoration.

How Do Property Rights Work for Abandoned Ghost Town Sites?

Like Fort Delaware’s crumbling walls returning to marsh, abandoned ghost town property ownership remains with original titleholders unless you’ve occupied land continuously for twenty years, paid taxes, and made improvements—but land reclamation through adverse possession never applies to government-owned sites.

What Caused Native American Populations to Decline in Delaware’s Ghost Towns?

You’ll find that disease outbreaks decimated 90% of Delaware’s Native populations between 1600-1700, while colonial expansion through Dutch and English settlements forced systematic displacement. Wars, land seizures, and eventual removal westward emptied their ancestral territories completely.

References

- http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/history/usa/de.htm

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/abandoned-industrial-ruin-garden-wilmington-dupont-crowninshield-180981544/

- https://www.narratively.com/p/the-park-built-on-forgotten-ghost-towns

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ex8Hld_imPU

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UAkxBOSLhs

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/delaware/abandoned-places-delaware

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UT_OjLP_geM

- https://archivesfiles.delaware.gov/ebooks/Wilmington_Delaware_Portrait_of_an_Industrial_City.pdf

- https://www.visitkeweenaw.com/listing/delaware-the-ghost-town/515/

- https://www.fortdelaware.org/Fort DuPont.htm