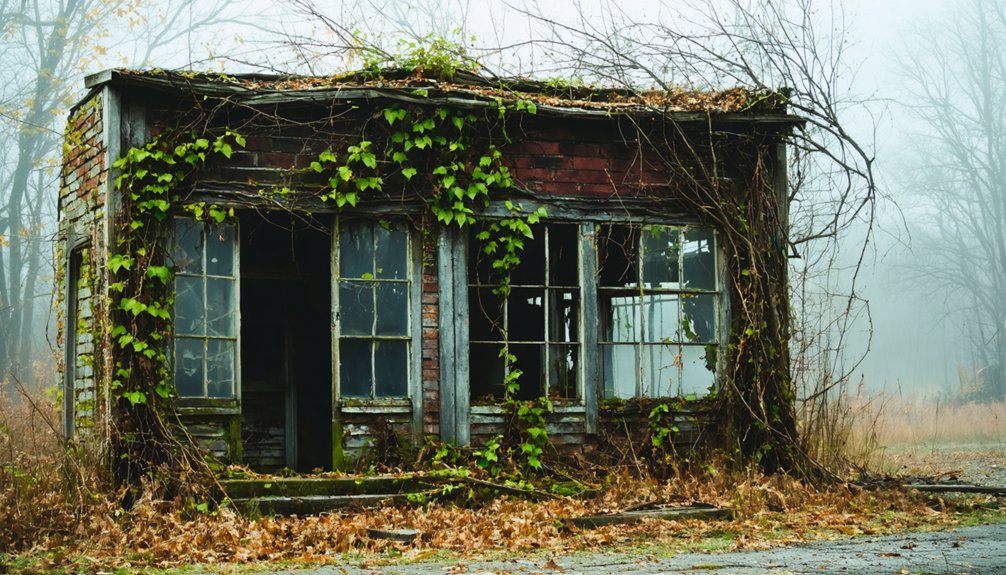

Wisconsin’s ghost towns demonstrate nature’s relentless reclamation as forests consume settlements like Dover, where graves disappear beneath undergrowth since the 1870 abandonment, and Imalone’s Bible camp structures deteriorate along the Chippewa River. You’ll find Paradise Springs’ Gothic ruins sheltered within Kettle Moraine State Forest, while Clifton’s limestone quarries hide behind High Cliff State Park’s advancing vegetation. These sites preserve architectural fragments—from Pendarvis’s restored Cornish cottages to Helena’s isolated cemetery—creating archaeological landscapes where ecological succession systematically erases nineteenth-century ambitions, revealing compelling narratives about Wisconsin’s industrial and social transformations.

Key Takeaways

- Paradise Springs’ elaborate spring house and copper dome were demolished in the 1970s, leaving only Gothic ruins within Kettle Moraine State Forest.

- Dover’s scattered graves have been reclaimed by forest after the entire population departed by 1870 following railroad relocation.

- Helena’s cemetery remains as a remnant after the town experienced three relocations and eventual abandonment due to industry collapse.

- Imalone’s abandoned Bible camp structures and deteriorating taverns face ongoing decay along the Chippewa River since the 1940s era.

- Clifton’s small cemetery lies hidden within brush at High Cliff State Park, marking the abandoned 1870s limestone quarrying settlement.

Paradise Springs: Where Milwaukee’s Elite Playground Meets Gothic Ruins

How does a nineteenth-century Prussian settlement transform into Milwaukee’s premier leisure destination, only to return to wilderness within a century?

You’ll find the answer at Paradise Springs, where fieldstone walls stand as monuments to ambition and abandonment.

Prussian immigrants established this settlement in the 1850s, constructing the elaborate spring house around 1900 with its now-vanished copper dome.

German craftsmanship met American wilderness when Prussian settlers built their ornate spring house crowned with copper beneath Wisconsin skies.

The 1920s brought horse tracks, a massive two-story hotel, and bottling operations that shipped Natural Spring Water across the region.

The spring’s consistent 47-degree temperature made it invaluable for the Pettit family’s estate operations and later commercial ventures.

The natural spring drove this commercial empire by releasing approximately 30,000 gallons of water every hour.

By the 1970s, demolition crews erased the resort infrastructure, leaving only ruins along today’s nature trail.

You’re free to explore these Gothic remnants within the Kettle Moraine State Forest, where nature’s reclamation demonstrates wilderness’s patient power over human enterprise.

Pendarvis: Cornish Mining Heritage Frozen in Time

While most ghost towns crumble into oblivion, Pendarvis stands as southwestern Wisconsin’s deliberate act of memory—a cluster of limestone cottages where Cornish miners’ descendants rescued their ancestors’ architecture from extinction.

You’ll find these Cornish cottages nestled in Mineral Point, constructed from local galena limestone by immigrants fleeing England’s depleted tin mines between 1830 and 1850.

When Robert Neal and Edgar Hellum purchased their first cottage for $10 in the 1930s, they weren’t just saving buildings—they preserved an entire mining legacy. The restoration would eventually expand to include Polperro and Trelawny, additional houses given Cornish names that honored the immigrants’ homeland.

The Ho-Chunk had extracted lead here for centuries before badger-like prospector holes earned Wisconsin its nickname.

Their restoration efforts extended beyond architecture when Neal and Hellum opened a small restaurant in 1935, serving only authentic Cornish pasties to about twenty guests by reservation.

Today’s Wisconsin Historical Society site interprets this extraction economy through restored architecture, transforming near-ruins into accessible history.

You’re witnessing preservation as resistance against erasure, where stone outlasts memory’s fragility.

Helena and Dover: Railroad Ghosts of Iowa County

Railroad companies didn’t just bypass Helena and Dover—they erased them from Iowa County’s economic map with surgical precision.

Helena’s ghost town decline began when the lead industry collapsed and tracks veered elsewhere, despite its strategic shot tower location. The settlement had already relocated twice seeking prosperity, only to face abandonment after the Black Hawk War. The town experienced three different locations along the Wisconsin River before its final disappearance.

Dover’s fate proved equally brutal. When farmers demanded excessive prices for depot land, the Milwaukee and Mississippi River Railroad simply chose Mazomanie instead. Residents literally moved their houses to follow the rails, leaving Dover’s population at zero by 1870. The British Temperance Emigration Society had founded Dover in 1844 with 700 settlers seeking new opportunities in Wisconsin Territory.

Today, Helena’s cemetery and shot tower site mark where industrial ambition met transportation reality, while Dover exists only as scattered graves reclaimed by forest.

Imalone: Bible Camp Memories Swallowed by the Wilderness

Born from a moment of linguistic confusion, Imalone emerged when gas station employee Bill Granger’s literal response—”I’m alone”—became a proper noun through a salesman’s transcription.

A gas station worker’s existential answer transformed into geography when someone mistook loneliness for a place name.

You’ll find this Northern Wisconsin settlement reclaimed by wilderness, where Imalone nostalgia centers on Rev. Olaf Newhagen’s 1940 Bible camp that once drew youth from Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota.

Softball fields and tennis courts now surrender to vegetation, while the Bible camp legacy fades alongside abandoned structures documented in 2007 and 2016.

The Chippewa River still flows past deteriorating taverns and a concrete silo—remnants of logging prosperity.

Doctrinal disputes fractured the church after Newhagen’s death, scattering congregants.

Today’s MapQuest confirmation feels ironic: you can pinpoint a ghost town where freedom meant Saturday dances and summer retreats, now returned to solitude.

Clifton: Limestone Legacy Within High Cliff State Park

Where the Niagara Escarpment meets Lake Winnebago’s western shore, Clifton’s limestone quarries carved deep into bedrock before forest reclaimed the scars.

This ghost town flourished through the 1850s-1870s, extracting building materials that fueled Wisconsin’s infrastructure expansion. When deposits exhausted by the late 1870s, workers abandoned their settlement to nature’s patient advance.

Today’s High Cliff State Park preserves this quarry history through accessible trails where you’ll discover:

- Collapsed kiln foundations buried beneath hardwood canopy

- Overgrown shafts and dugouts reclaimed by native vegetation

- Worker cabin remnants disappearing into forest floor

You’re free to explore these industrial relics transformed into ecological study sites.

The ghost town demonstrates nature’s resilience—limestone extraction zones now support thriving biodiversity, proving abandoned human enterprise becomes wildlife sanctuary when left undisturbed along Wisconsin’s dramatic escarpment terrain. A small cemetery hidden within the surrounding brush marks the final resting place of early quarry workers and their families. Old gravestones still stand sentinel among the undergrowth, weathered testaments to the community that once thrived here.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Wisconsin Ghost Towns Safe to Explore Without a Guide?

You’ll need thorough safety precautions before attempting solo urban exploration. Research ownership status, structural stability, and environmental hazards beforehand. While you’re free to explore public sites independently, private locations require permission to avoid legal consequences.

What Permits Are Needed to Photograph Ghost Town Ruins?

Photography permits aren’t required for abandoned ghost towns on public land, though you’ll face legal considerations if sites are privately owned. About 60% of Wisconsin’s ghost towns remain unprotected, offering you unrestricted photographic freedom.

Can You Camp Overnight Near These Abandoned Wisconsin Sites?

You’ll find overnight camping isn’t permitted directly at abandoned sites due to private property restrictions, but nearby state parks and county forests offer legal primitive camping with proper overnight permits following DNR camping regulations.

Which Ghost Town Is Best for Wheelchair Accessibility?

No Wisconsin ghost towns currently offer wheelchair trails or documented accessibility features. You’ll find these abandoned sites lack ADA compliance due to structural decay, overgrown vegetation, and absence of maintained pathways through reclaimed wilderness areas.

Are There Ghost Tours Available at These Locations?

Like abandoned memories fading into wilderness, you won’t find organized ghost tour experiences at these reclaimed sites. They lack local haunting legends or commercial operations—nature’s quiet reclamation has erased both human stories and structured tourism infrastructure.

References

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/wisconsin/wi-paradise-springs

- https://lakecountrytribune.com/exploring-the-haunting-echoes-of-wisconsins-ghost-towns/

- https://www.wisconservation.org/ghosts-quincy-bluff-wetlands-state-natural-area/

- http://shunpikingtoheaven.blogspot.com/2016/05/a-wisconsin-ghost-town.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Wisconsin

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4E0ZVZTSb4

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/lists/abandoned-places-midwest

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/trip-ideas/wisconsin/ghost-town-fall-wi

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pfGSkH96epE

- https://thesecretgardenatlas.wordpress.com/2013/06/25/paradise-springs-nature-trail-wisconsin-usa/