You’ll find Delaware’s ghost towns particularly haunting in fall, from Fort Delaware’s granite fortress on Pea Patch Island—where 2,400 Confederate prisoners died—to Glenville, abandoned after 2003’s catastrophic flooding submerged 200 homes under 12 feet of water. Explore Owens Station’s weathered railroad remnants, Saint Johnstown’s 1872 Methodist church ruins, or Zwaanendael’s 1631 colonial site at Cape Henlopen. Mid-October offers perfect weather, vibrant foliage, and fewer crowds as you navigate these sites where history, disaster, and nature converge into Delaware’s most compelling autumn destinations.

Key Takeaways

- Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island offers haunted Civil War prison history with massive brick fortress and large heronry habitats.

- Glenville, Delaware’s youngest ghost town, was abandoned after 2003 flooding with visible weathered roads and reclaimed natural landscapes.

- Zwaanendael Museum in Lewes showcases Delaware’s 1631 Dutch colony through maritime artifacts and colonial history near accessible beaches.

- Fenwick Island Lighthouse, an 1856 decommissioned sentinel, features preserved grounds and museum near the Transpeninsular Marker.

- Mid-October offers optimal visiting conditions with peak fall foliage, fewer crowds, and temperatures ranging from 40°F to 70°F.

Fort Delaware: A Haunted Prison on Pea Patch Island

Rising from the murky waters of the Delaware River like a granite sentinel, Fort Delaware commands Pea Patch Island with the imposing presence of America’s largest brick-and-granite fortress.

You’ll reach this isolated stronghold via ferry, where haunted legends echo through corridors that once imprisoned 33,000 Confederate soldiers during the Civil War.

Over 2,400 souls perished here, their spirits allegedly wandering the medieval-style moat and granite walls completed in 1859.

The isolation appeal draws those seeking authentic encounters with America’s darkest chapter.

You’ll experience hands-on history within Joseph Totten’s Third System masterpiece, where documented escapes and untold suffering left indelible marks.

The fort’s foundations rest on 4,911 wooden piles driven deep into the island’s soft, muddy soil, a remarkable engineering feat that keeps the massive structure stable to this day.

Beyond the fortress walls, the island hosts one of the largest heronries in the Eastern United States, where thousands of wading birds nest in a striking contrast to the site’s dark history.

This autumn, explore the causeway entrance and imagine desperate prisoners plotting freedom while herons now nest where guards once patrolled.

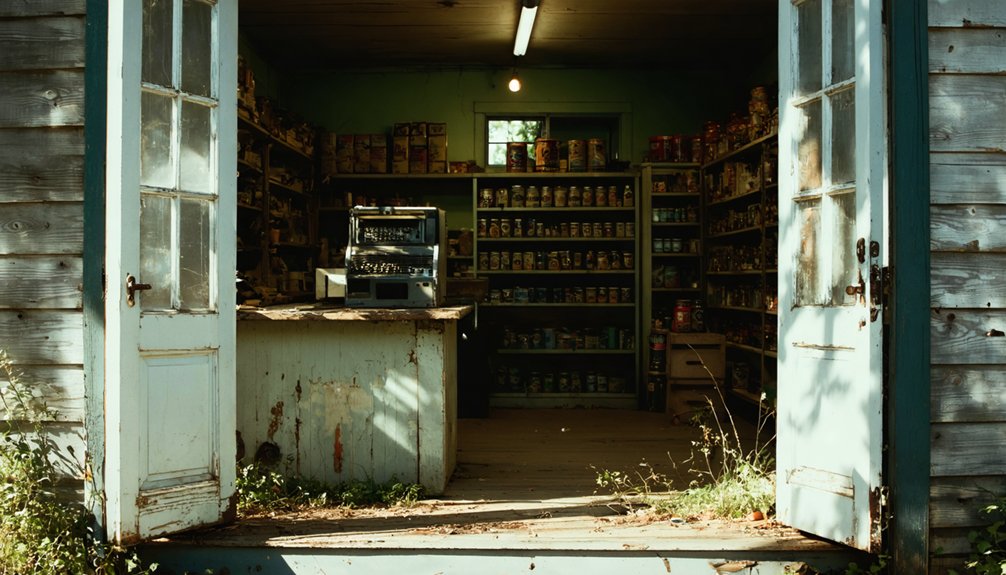

Glenville: Delaware’s Modern Ghost Town

Unlike Delaware’s colonial-era ghost towns, Glenville’s story is heartbreakingly recent—families abandoned their homes here just two decades ago after Tropical Storm Henri’s floodwaters devastated this Red Clay Creek neighborhood in 2003.

You’ll find the site eerily empty now, transformed from a thriving suburban community into scattered remnants hidden among overgrown vegetation near Stanton.

The town’s vulnerability stemmed from its location on a floodplain near waterways, which made it susceptible to repeated natural disasters.

Several ruined buildings still dot the landscape, offering ghostly evidence of the homes and lives that once flourished here.

The crumbling foundations and cracked driveways you’ll spot today stand as haunting reminders that ghost towns aren’t just relics of the distant past—they’re still being created in modern Delaware.

As you explore these eerie landscapes, you’ll come across colonial ghost towns in the US that tell stories of forgotten lives and aspirations. Each abandoned building whispers tales of the time when bustling communities thrived, now reduced to mere shadows of their former selves. These sites serve as silent witnesses to historical changes, captivating adventurers and history buffs alike with their unique allure.

Recent Abandonment After 2003

While most of Delaware’s ghost towns slowly crumbled over decades, Glenville met a swift and methodical end in the early 2000s. After Hurricane Floyd’s devastating 1999 assault and repeated floods battered Bread and Cheese Island, state authorities launched a thorough community relocation program.

By 2004, every family had accepted buyouts and moved to higher ground, leaving behind painted pleas on vacant homes seeking last-minute buyers.

The floodplain recovery effort transformed this once-thriving neighborhood into Delaware’s newest ghost town.

Demolition crews razed structures throughout 2005, erasing nearly all physical evidence of the community.

Today, you’ll find only weathered roads and security fences blocking access to what remains.

It’s a bittersweet confirmation to government intervention—residents escaped disaster, but at the cost of completely erasing their neighborhood from Delaware’s landscape.

Tropical Storm Henri Damage

On September 15, 2003, Tropical Storm Henri released a catastrophic deluge that would permanently erase Glenville from Delaware’s map.

Ten inches of rain in five hours submerged the subdivision under twelve feet of water, destroying 194 homes.

Red Clay Creek’s flow reached 16,000 cfs—the most extreme flood on record, exceeding 500-year levels.

You’ll find few haunted locations more authentically chilling than abandoned Glenville.

Helicopters plucked residents from rooftops while emergency responders struggled through invisible neighborhoods.

The devastation prompted an unprecedented response: Delaware purchased 171 homes, transforming suburbia into wetlands.

Among the chaos, postal worker Joseph Grabauskas assisted rescue teams by identifying house addresses during the five-hour evacuation effort.

Today, urban legends swirl around these former streets.

Nature’s reclaimed what civilization built, creating Delaware’s youngest ghost town—a haunting reminder of water’s unstoppable power.

Hidden Remnants and Ruins

Though fencing now guards the perimeter, you’ll discover Glenville’s ghostly footprint etched into Delaware’s landscape like a fading photograph. Old roads still snake through the floodplain, their cracked asphalt leading nowhere. You’re witnessing urban decay with a conscience—where demolition crews erased 180+ homes but couldn’t quite erase memory.

Before wrecking balls swung in 2005, desperate messages painted on walls pleaded for buyers, transforming homes into final testimonies.

This historical preservation effort took an unusual form: documentation through intentional removal. Unlike Delaware’s other ghost towns left to rot, Glenville received government intervention and relocation assistance. The Red Cross documented the destruction during disaster relief work, capturing haunting images of abandoned structures before a storm sealed the community’s fate.

As you navigate the fenced boundary at twenty feet above sea level, you’re standing where fourteen catastrophic floods finally defeated human stubbornness. The silence speaks volumes about nature’s patient power.

Owens Station: A Forgotten Sussex County Settlement

You’ll find remnants at Beach Highway and Owens Road’s intersection, where weathered houses stand as silent witnesses to population decline that followed the railroad’s closure.

When tracks disappeared and land returned to original owners, economic lifeblood drained away.

The settlement began as a post village on the Queen Annes Railroad, established in 1894 to connect Queenstown and Lewes during summer months.

Today’s Owens Station Sporting Clays facility preserves the name, offering concealed carry classes and tournaments where trains once whistled through—a fitting tribute to Delaware’s independent spirit.

Saint Johnstown: Relics of a Vanished Community

Where railroad tracks once carried travelers between Ellendale and Greenwood, Saint Johnstown now exists as whispers and weathered wood. You’ll find its soul at 13471 St. Johnstown Road, where St. Johnstown Methodist Church stands as the community’s last witness.

Since Francis Asbury organized believers here in 1779, this ground has held faith through transformation and loss.

The 1872 church replaced an earlier structure, its walls echoing community legends from a time when the Queen Anne’s Railroad breathed life into settlements. Before any permanent structure existed, early Methodist gatherings took place in members’ homes and woodland clearings.

When the trains stopped, Saint Johnstown faded—tracks pulled up, railroad property returned, neighbors scattered.

Among Delaware’s historical landmarks, this ghost town rewards autumn visitors who appreciate freedom found in forgotten places. Like Michigan’s Delaware, where deteriorating structures now stand abandoned after the mining industry’s decline, Saint Johnstown represents the fragile nature of communities built on single industries.

A historical marker guides you to where determination built churches in wilderness, before progress moved on.

Zwaanendael: Delaware’s First Failed European Colony

Long before Saint Johnstown’s church bells rang or railroad tracks scarred Delaware’s soil, thirty-two Dutch settlers stepped ashore at Cape Henlopen with dreams of whale oil fortunes and beaver pelts. They called it Zwaanendael—”swan valley”—Delaware’s inaugural chapter in Dutch colonization.

By 1632, Native American conflicts ended their enterprise violently after settlers displayed a chief’s relative’s head on their fort gate. The Lenape left no survivors. The Dutch beaver fur trade with Native Americans had initially shown promise before the fatal disagreement destroyed the settlement.

Today, you’ll find Zwaanendael Museum in Lewes, a replica of Hoorn’s Dutch town hall, standing where ambition met catastrophe:

- Red-tiled architecture echoing 1631’s original palisaded fort

- Maritime artifacts from Delaware’s earliest European foothold

- Free admission to explore shipwreck relics and colonial history

- Walking distance to Cape Henlopen’s windswept beaches

The “First Town in the First State” remembers those who dared claim untamed shores—and paid dearly.

Fenwick Lighthouse: Abandoned Maritime Heritage

While Zwaanendael’s settlers met their fate defending a wooden palisade, another structure would later pierce Delaware’s coastal skyline with a singular purpose—to save lives rather than claim land.

You’ll find Fenwick Island Lighthouse standing 89 feet tall, born from shipwreck stories that plagued the treacherous Fenwick Shoals. Congress authorized its construction in 1856 after too many vessels met watery graves six miles offshore.

The lamp first blazed on August 1, 1859, its French lens burning whale oil while two keepers maintained lonely vigils with their families.

Though decommissioned in 1978, public outcry sparked lighthouse preservation efforts. Today you can explore the grounds and mini-museum, standing where the Transpeninsular Marker meets this sentinel of survival—a ghost tower relit, watching over waters it once tamed.

Planning Your Fall Ghost Town Adventure in Delaware

You’ll want to pack layers for Delaware’s unpredictable fall weather—mornings at Fort Saulsbury’s crumbling bunkers hover around 40°F while midday explorations of Sussex County ruins can warm to 70°F.

Sturdy boots are non-negotiable on the uneven terrain of sites like Old Furnace, where centuries-old foundations hide beneath fallen leaves and twisted roots.

Plan your route along US 13 and SH 9 for weekday visits in mid-October, when the northern counties blaze with foliage and you’ll have these forgotten places mostly to yourself.

Essential Gear and Safety

As October’s chill settles over Delaware’s forgotten corners, proper preparation transforms from suggestion to necessity. You’ll need waterproof hiking boots with aggressive tread for traversing muddy trails around sites like Glenville and Owens Station, where historical relevance outweighs comfort.

Delaware’s preservation efforts haven’t reached these abandoned places—you’re entering raw, unforgiving territory.

Pack strategically for Delaware’s unpredictable coastal weather:

- Navigation essentials: GPS with offline maps, compass, and headlamp for cell-dead zones around Woodland Beach

- Weather protection: Layered waterproof clothing for 50-65°F days dropping to 35°F nights, plus emergency blanket

- Safety fundamentals: First aid kit, whistle, multi-tool for dilapidated structures

- Communication backup: Portable charger and written itinerary shared with others before exploring isolated sites

Remember—nor’easters strike fast, transforming accessible ghost towns into genuine survival situations.

Best Routes and Timing

With your emergency supplies secured, Delaware’s ghost town circuit awaits strategic planning—and timing determines whether you’ll photograph atmospheric ruins bathed in golden light or stumble through pitch-dark shells at 4:30 PM. Target mid-October weekdays when fall foliage peaks across New Castle County’s northern corridor—you’ll dodge weekend crowds while capturing maples ablaze against crumbling foundations.

Start Wilmington mornings, driving US 202 west toward Nemours before looping SH 141 to Pea Patch Island’s fort ruins (15 miles total). Central Kent County offers compact exploration: Smyrna to Leipsic spans just 9 miles of 18th-century plantation remnants.

Southern Sussex routes connect Lewes to Pine Grove Furnace through 25-minute rural stretches. Between sites, detour for local cuisine in thriving towns—Delaware’s apple cider and pumpkin fare fuels authentic autumn exploration.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Ghost Town Visits in Delaware Safe for Children and Families?

Yes, Delaware’s ghost towns offer safe family exploration where you’ll discover haunted legends through peaceful trails and historical preservation sites. You’re free to wander abandoned settlements without physical dangers, making them perfect for curious adventurers of all ages.

Do I Need Special Permits to Explore Abandoned Sites in Delaware?

Most Delaware ghost towns don’t require permits—you’ll find public roads lead to Woodland Beach and Saint Johnstown freely. However, respect legal restrictions on private properties and historical preservation sites. State parks charge standard fees, not special permits.

What Photography Equipment Works Best for Ghost Town Exploration in Fall?

You’ll want a wide-angle lens like the 16-35mm f/2.8 to capture haunting historical photography in cramped ruins, while autumn lighting demands a sturdy tripod for longer exposures. Don’t forget your flashlight—darkness hides secrets and hazards alike.

Are There Guided Tours Available for Delaware’s Ghost Towns?

Delaware doesn’t offer traditional ghost town tours, but you’ll find haunted historical tours exploring local legends instead. These experiences feature historical signage, colonial-era sites, and paranormal investigations that’ll satisfy your craving for mysterious, off-the-beaten-path adventures.

Can I Camp Overnight Near Any of Delaware’s Ghost Town Locations?

You’ll find campgrounds within minutes of Delaware’s haunted sites, though not directly in ghost towns. Cape Henlopen and Lums Pond offer the closest access. Make campground reservations early—fall weather draws peak crowds seeking paranormal adventures near historic locations.

References

- http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/history/usa/de.htm

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Delaware

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ex8Hld_imPU

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.farmweddingde.com/wedding-blog/haunted-history-in-delaware-city-tourism-in-the-first-state

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/delaware/abandoned-places-delaware

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UAkxBOSLhs

- https://delawarestateparks.blog/2020/05/04/history-of-pea-patch-island/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Delaware

- https://www.battlefields.org/visit/heritage-sites/fort-delaware-state-park