You’ll find Delaware’s most haunting spring destinations at Zwaanendael near Lewes, where Dutch settlers met their tragic end in 1631, and recently-abandoned Glenville, flooded and demolished after 2003’s Hurricane Henri. Explore Fort Delaware’s medieval gates on Pea Patch Island via seasonal ferry, then venture down Sussex County’s rural highways where collapsing potato barns and vine-choked granaries emerge from winter dormancy. The Brandywine Valley’s powder mill ruins and coastal lighthouse remnants complete your ghost town circuit, with each site revealing deeper stories of Delaware’s forgotten communities.

Key Takeaways

- Glenville, Delaware’s most recent ghost town, was abandoned in 2003 after Hurricane Henri flooding and demolished in 2005.

- Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island offers spring ferry access to Civil War-era ruins and military fortifications.

- Sussex County features abandoned agricultural communities with collapsing barns, granaries, and potato houses near rural highways.

- Zwaanendael Museum in Lewes commemorates Delaware’s 1631 Dutch settlement destroyed within a year, featuring the De Vries Monument.

- Brandywine Valley’s industrial ruins include Eleutherian Mills and powder yard remnants preserved at Hagley Museum.

Zwaanendael: Delaware’s First European Settlement

Long before William Penn set foot in the New World, Dutch settlers were already carving out their dreams along Delaware’s coast. In 1631, they established Zwaanendael—”Valley of the Swans”—near present-day Lewes.

You’ll find this pioneering spirit commemorated at the Zwaanendael Museum, where historical preservation brings their story alive.

The settlement lasted barely a year. Cultural misunderstandings with local tribes sparked violence that destroyed everything. When founder David Pietersz de Vries returned in December 1632, he discovered only charred ruins. The colony’s destruction stemmed from a dispute over a painted tin that led to the killing of a local chief and subsequent revenge attacks.

Today, you’re free to explore this haunting legacy. Visit the museum Wednesdays through Saturdays (admission’s free), then seek out the De Vries Monument on Pilottown Road. This monument was dedicated in 1909 and honors the memory of Delaware’s first European settlers.

It’s Delaware’s original ghost town—proof that America’s quest for independence started right here.

Fort Delaware and Pea Patch Island’s Military History

While paddling across the Delaware River today, you’ll spot Pea Patch Island rising from the water like a fortress from another era. Fort Delaware‘s massive pentagonal walls represent prime military architecture—built between 1848 and 1860 as one of America’s largest coastal defense installations.

French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant first recognized this strategic chokepoint in the 1790s, controlling access to Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Trenton. Foundation construction involved driving nearly 5,000 piles into the island’s soft mud, reaching depths of about 40 feet to support the massive fortification.

During the Civil War, these walls imprisoned over 30,000 Confederate soldiers, with 12,000 confined simultaneously. Extreme weather and inadequate shelter created unsanitary conditions that caused nearly 3,000 prisoner deaths, with victims buried at Finns Point National Cemetery across the river.

You’ll discover haunting industrial archaeology throughout—from medieval-style portcullis gates to World War I gun emplacements scrapped in 1943.

Spring ferry rides transport you directly to this preserved military complex, where escape tunnels and officers’ quarters tell stories of desperate prisoners who once swam toward freedom.

Glenville: The State’s Most Recent Ghost Town

You’ll find Glenville’s haunting remnants in southwest New Castle County, just south of Route 4 near Stanton—Delaware’s newest ghost town, abandoned after Tropical Storm Henri’s floodwaters devastated the community in September 2003.

By 2004, every resident had evacuated this doomed settlement on Bread and Cheese Island, their homes left empty with desperate “For Sale” signs painted on walls before demolition crews arrived in 2005.

When you visit in spring, the flood-scarred landscape along Red Clay Creek tells the story of a modern neighborhood swallowed by nature’s fury.

The town’s deep historical roots traced back to 1679, making its recent abandonment all the more poignant for those who knew its centuries-long legacy.

Glenville was originally developed as a 20th-century housing development before the catastrophic flood sealed its fate.

Its empty foundations serve as stark reminders that ghost towns aren’t just relics of the Old West.

Tropical Storm Henri Devastation

On September 15, 2003, Tropical Storm Henri released a catastrophic deluge that would erase an entire Delaware community from the map. You’d struggle to comprehend how five hours of rainfall—over 10 inches—transformed Red Clay Creek into a raging torrent that swallowed Glenville beneath 12 feet of water.

Residents trapped in their homes watched helplessly as helicopters plucked neighbors from rooftops while 194 houses disappeared underwater.

This wasn’t just poor hurricane preparedness—Glenville’s location on a floodplain practically invited disaster.

The $19.6 million devastation prompted unprecedented government buyouts of 171 homes, the largest storm-damage acquisition in Delaware’s history. Among those who responded to the crisis was local postal carrier Joseph Grabauskas, who spent over five hours helping emergency responders identify house addresses and rescue trapped residents, including two children and two Great Danes from the murky floodwaters.

Today, where families once barbecued and kids played, you’ll find wetlands dedicated to flood mitigation, a sobering reminder that nature eventually reclaims what shouldn’t have been developed.

2004 Mass Resident Exodus

Unlike the slow abandonment that characterizes most ghost towns, Glenville’s transformation happened with bureaucratic precision. You won’t find typical urban decay here—state and local governments orchestrated a complete buyout program following the catastrophic 2003 flooding.

By 2004, population decline reached absolute zero as families accepted relocation assistance to escape the floodplain’s perpetual threat.

This wasn’t organic abandonment; it was managed exodus. Residential buildings came down systematically starting in 2005, erasing the 20th-century subdivision from Bread and Cheese Island.

The government’s intervention created Delaware’s most recent ghost town, though “ghost town” feels wrong when residents didn’t flee poverty or disaster—they were compensated and relocated.

You’ll find hints of community history remain, but this bittersweet ending proved far gentler than decay-driven abandonment.

Southwest Newcastle County Location

Glenville sits tucked away in southwest New Castle County, on a piece of land locals call Bread and Cheese Island—a name that feels almost whimsical for a place with such a tragic recent history. You’ll find it along Red Clay Creek‘s eastern bank, just south of Route 4 near Stanton, where environmental restoration has reclaimed what urban decay left behind.

Navigate to this ghost town by noting:

- Elevation at 20 feet makes flooding inevitable during heavy rains

- 302 area code marks Delaware coordinates (UTC-5, EST)

- Red Clay Creek’s proximity caused 14 catastrophic floods since 1937

- All 180+ homes demolished after 2003’s final disaster

Unlike century-old ruins elsewhere, Glenville‘s emptiness feels raw. You’re witnessing government-assisted escape rather than slow abandonment—a bittersweet freedom from nature’s relentless power.

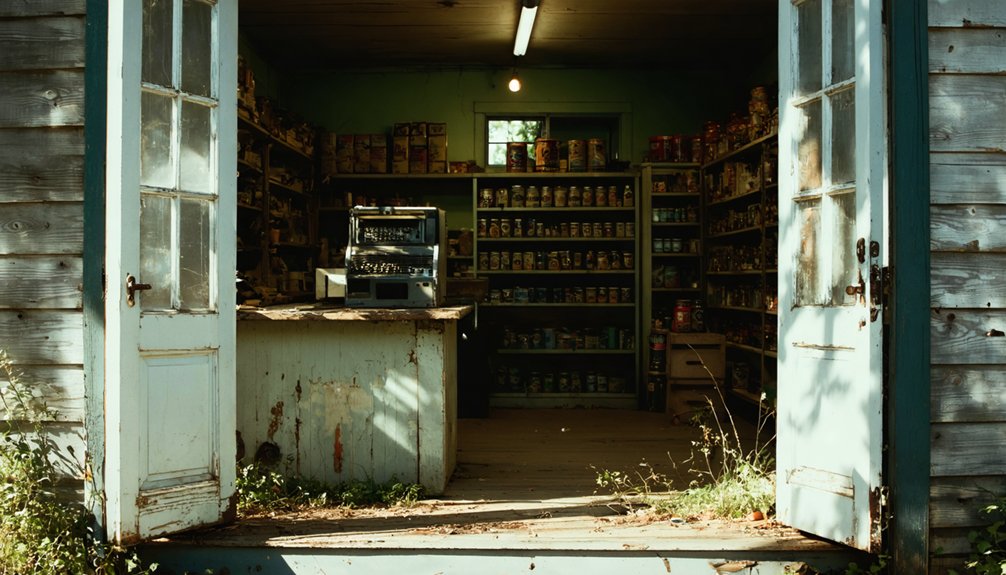

Sussex County’s Forgotten Agricultural Communities

You’ll find Sussex County’s most haunting agricultural ruins scattered across its western reaches, where collapsing barns and vine-choked granaries mark farms abandoned during the county’s economic pivot from grain cultivation to coastal development.

Start your exploration near Robinsonville, where crumbling silos rise from overgrown fields like skeletal sentinels. Their rusted metal skin peeling away to reveal the timber bones beneath. These ivy-covered structures throughout Sussex County showcase the state’s deep agrarian history, standing as visual evidence of rural decline and aging infrastructure.

Pack sturdy boots for these sites—springtime vegetation conceals uneven ground around deteriorating mill foundations and forgotten iron furnace operations that once powered the region’s 19th-century prosperity. The landscape transformation reflects how 43,000 acres of forestland vanished between 1998 and 2021 as development replaced natural terrain with housing and commercial structures.

Robinsonville’s Rural Remnants Today

Tucked away at the three-way junction where Robinsonville Road meets Kendale Road in southwestern Sussex County, this forgotten agricultural settlement exists now as whispers in the landscape. You’ll find rural landscape preservation has left scattered clues of Robinsonville’s existence across plowed fields and wooded terrain.

Spring’s your ideal window for discovering ancient settlement traces:

- Foundation outlines emerge from winter’s decay in surrounding woods

- Cellar holes reveal themselves before summer vegetation obscures them

- Aerial patterns show dispersed homestead locations across farmland

- Road networks connect remnants between State Highways 23 and 24

You can access the site easily via maintained rural roads, exploring freely where agriculture once thrived. The settlement’s location southwest of Lewes marks it as part of a scattered rural dwelling pattern visible in historical aerial surveys. Look carefully—some evidence lies buried beneath modern asphalt, while other fragments wait in overgrown corners for curious explorers seeking Delaware’s vanished communities.

Agricultural Infrastructure in Decay

Across Sussex County’s pastoral landscape, crumbling potato houses stand sentinel over fields that once fed America’s sweet potato obsession. You’ll recognize these tall, narrow structures by their distinctive arched roofs and multi-layered siding—relics of Delaware’s agricultural peak before 1940’s black rot outbreak ended everything overnight.

Farm abandonment accelerated when these specialized crop storage buildings became worthless, their constant fire risks and depressed land values prompting demolitions across the county.

The Hunter Farm Complex offers your best glimpse into this vanished world, though decay threatens its survival. You’re witnessing the death throes of forgotten rural communities where enslaved laborers once worked tobacco fields, later replaced by grain, then sweet potatoes.

Iron Furnace Ghost Sites

- Deep Creek Furnace Site (1763) near Seaford on SH 46, where Jonathan Vaughn’s operation stretched four miles between furnace and forge.

- Farmer’s Delight along Cedar Creek Road—Delaware’s first archaeologically confirmed bloomery with visible slag pits.

- Millsborough Furnace remains, which cast railings for Independence Square before closing in 1879.

- Robinsonville’s dispersed settlement at SH 227 and SH 287, where spring wildflowers now reclaim industrial foundations.

These sites offer solitary exploration through landscapes where agricultural communities once thrived around furnace fires.

Abandoned Lighthouses Along Delaware’s Coast

Delaware’s coastal lighthouse legacy reads like a chronicle of battles against the Atlantic’s relentless power. You’ll discover maritime legends at every turn—from Cape Henlopen’s 1767 tower that surrendered to erosion in 1925, to the resilient Fenwick Island beacon still guiding mariners since 1859.

Delaware’s lighthouses stand as defiant monuments where human engineering collides with the Atlantic’s unforgiving erosive force.

Start at Delaware Breakwater Lighthouse, where lighthouse preservation efforts saved the 60.5-foot brown tower after its 1996 deactivation.

You can’t miss Mispillion’s relocated wood-frame survivor in Lewes’ Shipcarpenter Square, lightning-scarred but standing proud.

Harbor of Refuge’s 1926 structure remains your most dramatic destination—born from storm-destroyed predecessors, it’s weathered nearly a century of Atlantic fury.

These aren’t sanitized tourist stops. They’re raw testimonies to engineering ambition and nature’s supremacy, perfect for spring exploration before summer crowds arrive.

Industrial Ruins of the Brandywine River Valley

While lighthouses battled the Atlantic, inland foundries and mills waged their own war against economic obsolescence along the Brandywine River Valley.

You’ll discover Delaware’s gritty industrial archaeology at sites where 288 explosions once rattled workers’ homes and shattered windows in Philadelphia.

Essential stops for ruins preservation enthusiasts:

- Eleutherian Mills – Stone walls directed powder blasts toward Brandywine Creek from 1802 to 1921, leaving foundations where 228 workers died.

- Beaver Creek Mill Ruins (39.83993972159399, -75.55698975927805) – Trace mill races through collapsed sawmill stones embedded in streambeds.

- Hagley Museum grounds – Walk among the du Pont powder yards that supplied half the nation’s gunpowder before the Civil War.

- Charles Banks workers’ district – Explore downstream neighborhoods leveled by the catastrophic 1915 blast.

Spring reveals hidden foundations through bare branches.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Safety Precautions Should I Take When Visiting Abandoned Sites in Delaware?

Like Indiana Jones steering through ancient ruins, you’ll need proper hazard awareness and safety gear: sturdy boots, respirators for mold, hard hats for unstable structures, and always inform someone of your location before exploring Delaware’s forgotten places.

Are Any Delaware Ghost Towns Located on Private Property Requiring Permission?

Yes, several Delaware ghost towns sit on private property requiring visitor permission. You’ll need approval before exploring Allee House, Fort at Cedar Beach, and Nemours. Always respect boundaries—trespassing ruins access for everyone seeking historical adventure.

What Is the Best Time of Day to Photograph Abandoned Structures?

When should you shoot? Forget golden hour—midday’s your best bet for abandoned structures. Harsh sunlight creates dramatic interior contrasts through broken windows. Night photography works too, but you’ll need longer exposures to capture haunting details effectively.

Can I Bring My Dog When Exploring Delaware’s Ghost Town Locations?

You’ll need to check individual site policies before visiting, as regulations vary. When exploring dog-friendly trails near ghost towns, always follow pet safety tips: keep your furry companion leashed, bring water, and watch for hazardous debris.

Which Ghost Towns Offer the Easiest Accessibility for Elderly Visitors?

Auburn Valley State Park offers you the easiest access with ADA-compliant bridges and accessible pathways throughout. Zwaanendael Museum provides senior-friendly tours on its wheelchair-accessible first floor, letting you explore Delaware’s maritime heritage comfortably.

References

- http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/history/usa/de.htm

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Delaware

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ex8Hld_imPU

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/delaware/abandoned-places-delaware

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UAkxBOSLhs

- https://history.delaware.gov/zwaanendael-museum/zm_history/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zwaanendael_Colony

- https://abc30.com/videoClip/15784039/

- https://history.delaware.gov/zwaanendael-museum/