You’ll find entire communities submerged beneath Deep South reservoirs, deliberately flooded during mid-20th century dam construction. Fontana Lake covers towns like Judson with 26 relocated cemeteries, while Lake Hartwell hides Andersonville’s stone foundations and Harris family cemetery. Lake Jocassee preserves Mount Carmel Baptist Church Cemetery at 130–150 feet depth, alongside Attakulla Lodge ruins. Lake Marion buried Ferguson’s industrial infrastructure, displacing 2,500 residents. During drought drawdowns, you can observe foundations, headstones, and architectural remains that surface from these engineered floods. The article below documents what persists underwater and how you access these submerged archaeological sites.

Key Takeaways

- Fontana Lake submerged six Swain County towns during WWII, displacing communities and relocating over 1,000 graves from 26 cemeteries.

- Lake Hartwell flooded Andersonville in 1962, with stone foundations and cemeteries visible during droughts amid ghostly legends.

- Lake Jocassee covers towns like Attakulla Lodge at depths reaching 360 feet, with submerged churches and cemeteries still intact.

- Lake Marion and Lake Murray displaced over 7,500 residents combined, flooding nine communities and creating permanent underwater ghost towns.

- Droughts reveal submerged foundations, roadbeds, and grave markers, allowing divers and boaters to explore underwater historical sites.

Fontana Lake: Submerged Settlements of the Smoky Mountains

During World War II, the Tennessee Valley Authority flooded multiple communities in Swain County, North Carolina, to create Fontana Lake—a reservoir designed to power Fontana Dam’s hydroelectric operations. The dam primarily supplied electricity to the Aluminum Company of America for wartime production of ships, aircraft, and munitions.

You’ll find that entire settlements—Judson, Fontana, Bushnell, Forney, and Kirkland Branch—now rest beneath Western North Carolina‘s largest lake. Judson alone had 600 residents before submersion.

The federal government relocated your ancestors’ communities through eminent domain, moving 243 graves while abandoning 26 cemeteries containing over 1,000 graves. Historical architecture from these towns occasionally surfaces during extreme drawdowns, when steep banks expose foundations and remnants. Boaters can view these remains of Judson during lake drawdowns, including foundations and graves that emerge from the water.

Local folklore persists about the “Road to Nowhere”—an unfinished promise to provide cemetery access that symbolizes governmental betrayal of displaced families. Displaced residents received minimal compensation, with most families paid less than 50 cents per acre for their land before forced evacuation.

Lake Hartwell: The Drowned Town of Andersonville

When you examine Lake Hartwell’s depths in South Carolina, you’ll find Andersonville—a once-thriving river port founded in the early 1800s that vanished beneath 60–90 feet of water after the Army Corps of Engineers completed Hartwell Dam in 1962.

The town’s submersion preserved stone foundations, roadbeds, and the Harris family cemetery with 59 graves now resting on what survives as 400-acre Andersonville Island, marked by navigation buoys LBC1–LBC9. The settlement originally flourished near the confluence of Tugaloo and Seneca Rivers, where trade and travel thrived before the reservoir’s creation.

Drought conditions periodically expose these ruins and fuel persistent reports of apparitions and unexplained phenomena documented by divers, fishermen, and kayakers exploring the site. Locals describe phantom lights beneath the water’s surface, adding to the supernatural mystique surrounding the submerged town.

Andersonville’s Founding and Submersion

The historical record contradicts the premise that Andersonville lies beneath Lake Hartwell.

You’ll find Camp Sumter Prison standing in Macon County, southwest Georgia—nowhere near Lake Hartwell’s waters in the Piedmont region.

Historical preservation efforts transformed this site into a national cemetery in 1865, then incorporated it into the National Park System in 1970.

Archaeological investigations confirm the prison grounds remain intact and accessible above ground.

You can visit Andersonville National Historic Site today, where over 13,800 graves mark the national cemetery, and 150 annual burials continue.

The National Prisoner of War Museum opened there in 1998.

No submersion occurred.

Lake Hartwell’s creation through damming the Savannah River affected different communities entirely, leaving Andersonville’s documented history untouched by reservoir waters.

The prison was deliberately situated inland to avoid coastal attacks and remained in this remote location throughout its operation.

The stockade’s 15-foot-high wall enclosed the original 16.5-acre site when construction began in early 1864.

Underwater Remnants and Legends

Beneath Lake Hartwell’s surface, stone foundations and chimneys lie scattered across the lakebed at depths ranging from 60 to 90 feet, their positions shifting with seasonal variations in water elevation. These ancient relics from Andersonville’s industrial past attract divers willing to navigate murky conditions and limited visibility.

You’ll find:

- Weathered walls and structural remains documented by exploration teams descending to the old town site.

- Grave markers still visible despite cemetery relocations to Andersonville Baptist Church.

- Time-beaten roads on Andersonville Island marking the community’s former boundaries.

- Exposed highway infrastructure revealed during drought conditions when water levels drop noticeably.

Underwater mysteries persist through local accounts of phantom lights and strange presences. The submerged town shares its name with multiple historical locations, including the infamous Civil War prison camp, though this South Carolina settlement predates the lake’s creation.

Historical artifacts from the Southern Clock Factory occasionally surface at auctions, providing tangible evidence of this submerged settlement‘s preserved archaeological potential. The town’s prosperity ended when railroads bypassed Andersonville, accelerating its decline before the dam’s construction ultimately submerged its remains.

Lake Jocassee: Dive Into South Carolina’s Deepest Secrets

Located in the northwestern corner of South Carolina where Oconee and Pickens Counties meet, Lake Jocassee spans 7,500 acres with 75 miles of shoreline carved into the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Created in 1973 through Duke Power’s 385-foot dam, this reservoir submerged entire communities beneath waters reaching 300-360 feet deep.

You’ll find exceptional visibility of 20-50 feet, rivaling conditions typically associated with ancient shipwrecks and submerged caverns in tropical waters. The Mount Carmel Baptist Church Cemetery rests at 130-150 feet—the same location filmed in 1972’s Deliverance.

Attakulla Lodge sits at 300 feet, while a Chinese Junk lies at 35-50 feet. Year-round temperatures range from 44°F to 80°F, with four mountain rivers feeding the reservoir’s remarkable clarity and preserving these underwater historical sites. The lake sits at 1,100 ft elevation within the Appalachian temperate rainforest, surrounded by lush forests and waterfalls accessible only by boat. Four boat ramps provide access points for divers and boaters exploring these submerged historical sites.

Tellico and Calderwood Lakes: Buried Cherokee Heritage

Where Tennessee’s Little Tennessee River once flowed freely through ancestral Cherokee lands, Tellico and Calderwood Lakes now conceal seven major townsites—Chota, Tanasi, Toqua, Tomotley, Citico, Mialoqua, and Tuskegee—beneath their depths.

You’ll find these waters hide more than government wants acknowledged:

- Morganton ghost town (submerged 1979) where Sherman’s troops crossed in 1864

- Cherokee artifacts from 1762 uncovered during University of Tennessee’s 1978 survey

- Historic fort structures buried beneath Calderwood’s waters

- Submerged myths of unsettled souls haunting sacred sites

Tellico Dam’s gates closed November 29, 1979, after Congress exempted the project from Endangered Species Act protection.

Families received eviction notices November 13, 1979—their final resistance crushed despite Cherokee sacred lands lawsuits.

Today, only Morganton’s hilltop cemetery overlooks these engineered lakes that erased 170 years of river commerce and millennia of indigenous heritage.

Lake Marion: Ferguson’s Industrial Past Beneath the Waves

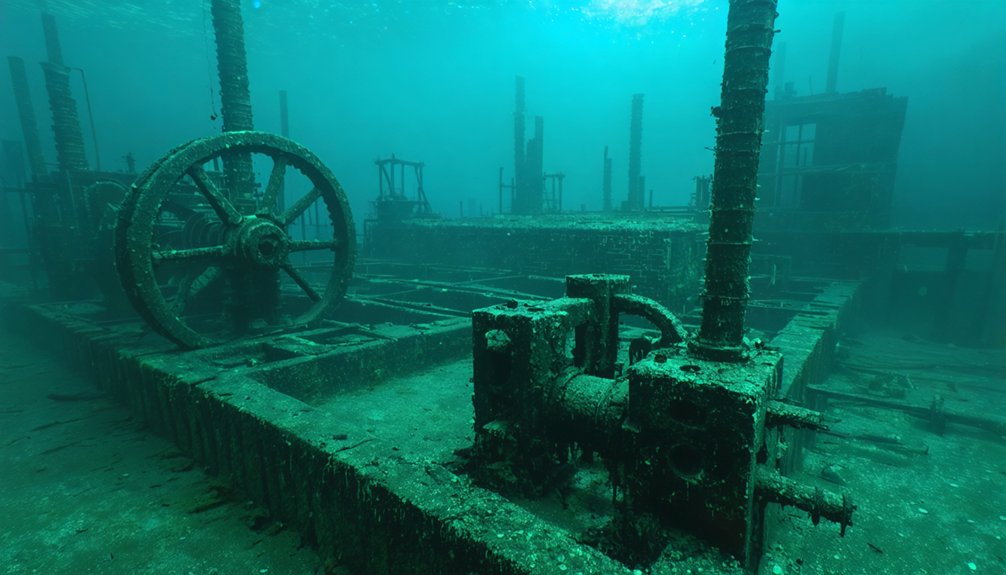

South Carolina’s Lake Marion conceals Ferguson, a sophisticated lumber-mill town that processed old-growth bald cypress from 165,000 acres of blackwater swamps between 1890 and 1915.

You’ll find remnants of historical architecture including steel bridges and mill structures above the waterline, evidence of Northern capitalists Beidler and Ferguson‘s 2,500-resident company town.

The operation employed innovative Lidgerwood pullboats and Duplex cableway systems for swamp extraction, producing creosote-treated railroad ties and finished lumber products.

Workers received company-store currency, binding them to Santee Mercantile Co.

The economic impact proved significant: timberland acquired at $2.00 per acre generated substantial profits as the South’s largest cypress operation.

The 1941 Santee-Cooper dam flooded this industrial site, displacing 2,500-3,000 residents while creating Depression-era hydroelectric infrastructure.

Lake Murray: Lost Communities of the Saluda River Valley

The Saluda River Valley attracted German, Swiss, and Dutch immigrants beginning in the 1750s, who established settlements including Dutch Fork and Saxe Gotha.

When South Carolina Electric & Gas Company purchased the land in the 1920s, they created Lake Murray—then the world’s largest man-made lake at 50,000 acres.

This construction displaced nearly 5,000 residents and submerged at least nine communities, transforming 75% wooded terrain into a reservoir that buried schools, churches, and entire town centers beneath its waters.

Early European Settlement History

During the 1700s, German, Dutch, and Swiss immigrants established foundational settlements throughout the Saluda River Valley, displacing Cherokee populations who’d farmed the fertile riverbanks for generations and designated the waterway as “river of corn.” These European settlers concentrated their communities adjacent to the river, capitalizing on transportation access and agricultural productivity that the valley’s soil conditions provided.

The settlement infrastructure developed systematically:

- Transportation corridors emerged connecting Hope Ferry and Dreher Ferry by the early twentieth century.

- Agricultural networks facilitated early colonial trade between backcountry producers and Charleston markets.

- Mill construction began with the 1830s Saluda Factory, South Carolina’s largest cotton operation.

- Canal systems enabled efficient cotton transport while Native American artifacts remained scattered throughout archaeological sites.

This European occupation fundamentally transformed the valley’s economic landscape.

Dutch Fork and Saxe Gotha

Beneath Lake Murray’s 500 miles of shoreline rest the submerged remnants of Dutch Fork and Saxe Gotha, settlements where approximately 5,000 German-speaking inhabitants established communities between the Broad and Saluda Rivers from the early 1700s forward.

The term “Dutch Fork” derives from *deutsch Volk*, reflecting the chiefly German-speaking settlers, alongside Swiss and Dutch immigrants who maintained their cultural identity into the early twentieth century.

These populations engaged in colonial trade networks while developing distinct material cultures, evidenced by ancient pottery fragments and architectural remains now documented through sonar technology.

Granby Village, established before 1774 as a Congaree River ferry settlement, served as a commercial hub.

Today’s exploration reveals churches, schools, and cemeteries across what became Newberry, Lexington, and Richland counties—physical evidence of autonomous communities claiming territory independent of external control.

Lake Creation and Transformation

When Thomas Clay Williams first proposed harnessing the Saluda, Santee, and Cooper rivers for hydroelectric power in 1916, he initiated a transformation that would permanently alter the region’s geographic and social landscape. Engineer William Spencer Murray expanded these plans, culminating in the Federal Power Commission‘s license grant to Lexington Water Power Company on July 8, 1927.

The construction’s environmental impact was profound:

- 100,000 acres purchased from approximately 5,000 residents

- Nearly dozen communities abandoned and submerged

- 65,000 acres covered by reservoir (75% woodland)

- 2,000 workers cleared land at 50 cents daily

Exploring Underwater Ghost Towns: What Remains Below

Although currents and sediment have claimed many artifacts, structural remains persist in remarkable condition across these submerged settlements.

At Lake Jocassee, you’ll find Attakulla Lodge’s foundations resting 300 feet down, while Mount Carmel Cemetery’s tombstones retain readable inscriptions.

Divers at Lake Hartwell document weathered walls and grave markers throughout Andersonville’s ruins.

Ferguson’s lumber kiln stands exposed on its island, with additional foundations emerging during low water events.

You can access Proctor’s remnants via backcountry trails, though Judson’s structures require extreme drawdowns for visibility.

These sites offer unique opportunities for underwater fishing and submerged navigation, but you’ll need proper authorization.

Pontoon boats provide surface reconnaissance, while technical divers conduct detailed documentation of intact architectural elements, cemetery markers, and industrial infrastructure preserved beneath Southern reservoir systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Other Underwater Ghost Towns in the Deep South?

Yes, you’ll find Butler, Tennessee submerged beneath Watauga Lake since 1948. These sites hold cultural significance for historical preservation efforts, documenting Appalachian heritage. You’re free to explore documented remnants through diving expeditions, revealing community foundations and architectural evidence.

Can Civilians Legally Dive to Explore These Submerged Structures?

Legal restrictions severely limit your access. You’ll need diving permits from agencies like NPS, TVA, or Army Corps before exploring most submerged structures. Federal reservoirs generally prohibit unauthorized dives, risking fines under archaeological protection laws.

Were Residents Compensated When Their Towns Were Flooded?

Compensation varied drastically across projects. You’ll find resettlement policies were inconsistently applied, with compensation disputes common among displaced residents. African American communities particularly faced inadequate payments, while documentation gaps prevent verification of equitable settlements in most cases.

How Long Did It Take to Relocate Entire Towns?

Town relocation timelines varied dramatically—you’d see St. Thomas’s seven-year flooding duration versus Loyston’s rapid five-year displacement. Each project’s scope determined your autonomy loss timeline, with most residents forced out within 3-7 years before complete submersion occurred.

Do Fish Inhabit the Old Buildings Underwater?

Yes, you’ll find marine biodiversity thriving around submerged underwater architecture. Divers document fish populations inhabiting flooded buildings, foundations, and structures in Deep South reservoir ghost towns, where ruins create shelter and feeding grounds for aquatic species.

References

- https://www.blueridgeoutdoors.com/go-outside/sunken-secrets-the-underwater-ghost-towns-of-the-blue-ridge/

- https://www.thewanderingappalachian.com/post/the-underwater-towns-of-appalachia

- https://lakehartwellguide.com/exploring-the-ghost-town-of-andersonville-lake-hartwells-sunken-mystery/

- https://clui.org/newsletter/spring-2005/immersed-remains-towns-submerged-america

- https://www.randomconnections.com/the-ghost-towns-of-lake-marion/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6gy0y6XFAo

- https://www.thesmokymountaintimes.com/local-news/under-water-stories-towns-lost-fontana-lake

- https://wlos.com/news/local/north-carolina-fontana-lake-proctor-town-submerged-underwater-history-100-years-ancestors-families-shorelines-world-war-2-lee-woods-historian

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CE3cdihJ0Y

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kx4_OBwu8k0