Delaware doesn’t have traditional ghost towns used for filming—instead, you’ll find preserved colonial settlements like New Castle and Lewes serving as authentic period backdrops. Productions favor these intact historic sites because cobblestone streets, 1700s architecture, and original structures minimize set construction costs while maximizing authenticity. Unlike abandoned locations, Delaware’s regulated historic districts offer legal clarity and logistical advantages for crews. Films like *Beloved* and *Dead Poets Society* capitalized on this preserved architecture rather than ruins, and understanding why filmmakers choose maintained sites over decayed ones reveals Delaware’s unique production strategy.

Key Takeaways

- Delaware lacks large-scale ghost towns; most abandoned sites are mills, military installations, or maritime industry remnants like Bancroft Mills.

- Ruins and storm-damaged locations like Glenville exist but are rarely used for filming due to preservation laws and logistical challenges.

- Filmmakers prefer intact historic structures over decayed sites, enabling quicker setup, lower costs, and compliance with strict preservation regulations.

- Military sites like Fort Miles are preserved for historical value but see minimal use as filming locations compared to maintained buildings.

- Well-preserved colonial towns like New Castle and educational campuses like St. Andrew’s School dominate Delaware’s filming landscape over ghost towns.

Delaware’s Historic Towns That Double as Film Sets

When location scouts search for authentic period settings, Delaware’s preserved colonial towns eliminate the need for elaborate set construction and CGI enhancements. You’ll find New Castle’s cobblestone streets and 1700s architecture providing naturally period-appropriate backdrops, as demonstrated when *Beloved* (1998) filmed there.

Technological advances haven’t diminished the value of these authentic environments—they’ve increased demand for them.

CGI can replicate anything, yet productions still seek Delaware’s genuine colonial architecture—proof that authenticity commands premium value in modern filmmaking.

Lewes offers compact coastal settings that streamline filming schedules. The town’s beaches have attracted filmmakers for Hallmark Channel productions and romantic comedies. While Wilmington’s urban infrastructure supports larger productions like *Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game* (2022), these locations give you freedom to capture multiple historical periods within Delaware’s borders without expensive modifications.

Modern festivals occasionally occupy these spaces, but historic preservation organizations prioritize production access, recognizing film work as economic development that maintains these architectural treasures. Delaware’s filming location category currently documents 14 films that have utilized the state’s geographic and architectural assets.

St. Andrew’s School: The Middletown Campus Behind Dead Poets Society

You’ll find St. Andrew’s School’s Gothic Revival buildings standing in for the fictional Welton Academy throughout *Dead Poets Society*. The campus’s stone facades, arched doorways, and slate roofs create the film’s austere New England aesthetic.

Director Peter Weir selected this location from over 200 schools specifically for its architectural authenticity—the same towers and courtyards where Robin Williams delivered his “carpe diem” speeches still anchor the 2,000-acre campus near Middletown. Founded in 1929 by A. Felix du Pont, the private Episcopal boarding school originally educated only boys before becoming coeducational in 1973.

The 1989 production utilized the school’s gym for indoor scenes, Noxontown Pond for lakeside sequences, and various classroom buildings to capture the rigid atmosphere of 1950s preparatory education. The school’s precise coordinates at 39.433308, -75.688805 mark its location among several Delaware filming sites that brought this beloved drama to life.

Gothic Architecture as Welton

Where else could filmmakers authentically capture the atmosphere of a 1950s prep school academy if not at St. Andrew’s medieval-inspired campus? You’ll find that director Peter Weir selected this Middletown location specifically for its Gothic revival stone architecture—irregular massings, mullioned windows with leaded lights, crenellated towers, and cloisters that Turner Construction Company built in 1929.

The architectural authenticity eliminated the need for elaborate set construction or period modifications. Arthur Howell Brockie designed these structures to resemble a medieval village rather than conventional institutional buildings, providing cinematographers with ready-made visual depth. The campus sits near Noxontown Pond, which enhanced the film’s scenic backdrop with its picturesque natural landscape.

You’re looking at 2,200 acres where every stone building reinforces the film’s themes of tradition and conformity. The campus didn’t require transformation into “Welton Academy”—it already embodied that restrictive, old-world educational establishment the narrative demanded. In 2019, the school completed a 29,000 square foot renovation of its science facilities, modernizing spaces originally built in 1967 while maintaining the campus’s historic character.

Robin Williams’ Iconic Scenes

Robin Williams transformed St. Andrew’s quiet campus into cinematic legend through his portrayal of John Keating.

You’ll find the classroom where he leaned forward behind students, whispering “Carpe…” during poetry lessons.

Science teacher Eric Kemer witnessed Williams standing alone between takes, staring at the ground in deep concentration.

The campus lacks traditional haunted legends or urban legends, but Williams’ presence created its own mythology.

He’d gather young actors in circles, delivering improvisational shtick that sparked genuine laughter.

The iconic “Oh Captain, My Captain” moments unfolded across campus exteriors, particularly around Pritchard Hall and Craig Hall.

The school’s location at 350 Noxontown Rd, Middletown serves as the primary address for fans seeking to visit the authentic Welton Academy setting.

St. Andrews School sits on 2,000 acres of farmland, providing the expansive pastoral backdrop that defined Welton Academy’s traditional atmosphere.

These locations now carry Williams’ artistic ghost, forever marking where he inspired both fictional students and real audiences seeking liberation through unconventional teaching.

New Castle’s Colonial Streets in Beloved and Independent Cinema

When you examine Beloved’s 1998 production in New Castle, you’ll find that director Jonathan Demme selected the location specifically for its cobblestone streets and colonial architecture that remain virtually unchanged since the 1700s.

The production team filmed key scenes along Battery Park’s waterfront and throughout the compact historic district, where over 500 preserved buildings from the 17th through 19th centuries eliminated the need for extensive period set construction.

You’ll notice how the town’s Dutch-established grid layout and concentrated four-block National Historic Landmark district provided Oprah Winfrey’s Civil War-era film with authentic 18th-century backdrops that independent filmmakers continue to utilize today. New Castle’s transportation hub status with its regional airport has made it increasingly accessible for film crews and production teams requiring period locations.

Beloved’s 1998 Production Design

New Castle’s colonial architecture became a practical solution for Beloved’s production design team when they needed authentic period streetscapes without extensive set construction.

You’ll find the town’s cobblestone streets and waterfront Battery Park delivered historical accuracy that complemented Philadelphia soundstage work.

Director Jonathan Demme’s crew captured colonial urban scenes here while Oprah Winfrey, Danny Glover, and Thandiwe Newton performed against genuine 18th-century facades.

The compact historic district minimized set restoration costs—preserved buildings already matched the adaptation of Toni Morrison’s novel.

You can trace the production’s strategic location choices: New Castle handled colonial street scenes, Philadelphia’s Old City and Manayunk provided additional urban backdrops, and rural locations supplied plantation fields.

This multi-site approach gave filmmakers maximum visual authenticity with minimal construction budgets.

The production’s local economic impact extended to Cecil County communities, where set constructions and filming activities generated revenue documented in regional articles.

Unchanged 1700s Architecture Appeal

What makes New Castle exceptional for period filmmaking isn’t just its preserved buildings—it’s the unchanged street grid and waterfront configuration that date back to Peter Stuyvesant’s 1651 settlement.

You’ll find sixty Federal-style structures built atop 1700s foundations, plus thirty-six buildings displaying authentic Georgian details from the 18th century. The Dutch House’s exposed ceiling beams and original timber framing provide ready-made colonial interiors without expensive set construction.

Architectural authenticity extends beyond facades—cobblestone streets and the riverfront layout survived the 1824 Great Fire.

While 1930s Colonial Revival restoration techniques prioritized visual charm over strict historical accuracy, they preserved over 600 structures spanning three centuries of occupation.

For filmmakers seeking 1700s America, you’re shooting in genuine colonial streetscapes where courts and assemblies actually convened.

Lewes Coastal Settings for Hallmark and Romantic Productions

Although Lewes hasn’t yet hosted a Hallmark production, its coastal architecture and historic settings position it as an ideal location for romantic films and television. You’ll find the Zwaanendael Museum modeled after a Dutch town hall, lighthouses dotting the coastline, and breakwaters offering cinematic backdrops.

The seaside charm extends to shipwreck sites and Revolutionary War locations accessible through walking tours—perfect for period romantic dramas.

The town’s historic charm proved its production value when “Dead Poets Society” filmed here in 1988-89, employing over 1,000 locals and drawing crowds to beaches hoping to glimpse stars at Lewes restaurants.

More recently, Taylor Sheridan’s “Lioness” brought the largest crew since that Robin Williams production.

Film commissioner TJ Healy calls it “the tip of the iceberg” for Delaware’s growing film industry.

Wilmington’s Urban Locations for Contemporary Storytelling

While Lewes captures period romance along the shore, Wilmington’s urban landscape offers production-ready venues for modern narratives.

Wilmington’s gritty urban settings deliver contemporary storytelling potential while coastal Lewes preserves historic charm for period productions.

You’ll find transformative locations like the Urban Artist Exchange Amphitheater at 16th and N. Walnut Streets—former police stables converted into event space showcasing urban decay aesthetics. Downtown delivers contemporary backdrops through Betsy’s Crêpes, Old Books on Front St, and Cotton Exchange establishments.

Modern infrastructure includes Cinespace Studios and Dark Horse Stages supporting 400+ productions since the 1980s, earning “Hollywood East” status.

Peerspace rentals average $108 hourly with daylight studios, lofts, and apartments booking 5-hour blocks. Productions typically accommodate 8 attendees starting midday.

Cameron Art Museum galleries and Brandywine Park’s fountain area provide polished alternatives.

You’ll access self-guided tours covering *One Tree Hill* and *Dawson’s Creek* sites across this production-friendly cityscape.

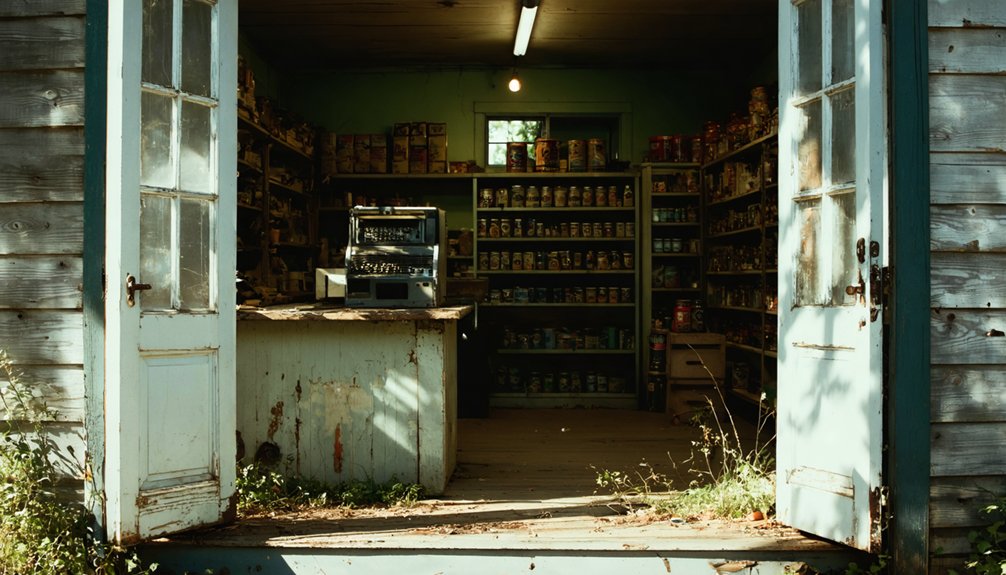

Why Delaware Has No Traditional Ghost Towns for Filming

Delaware’s abandoned landscape consists of industrial mills, agricultural structures, and maritime facilities rather than the expansive mining camps or boomtown settlements you’d find across Western states.

You’ll discover hundreds of small-scale abandonments—Bancroft Mills, Garrett Snuff Mill, Warren’s Mill remnants—but none match Rhyolite’s cinematic scale.

Historical preservation efforts focus on military sites like Fort Miles’ World War II bunkers, prioritizing documentation over filming access. Urban modernization eliminated most ruins through condo conversions or natural disaster damage.

Tropical Storm Henri destroyed Glenville by 2004, while Superstorm Sandy claimed Battery Park’s pier.

The eight ghost towns Wikipedia lists lack specific abandonment dates or preserved structures.

Fire damage at Bancroft Mills and nature-reclaimed sites like Reedy Island Range Light offer limited visual appeal.

You won’t find Delaware locations on national filming registries.

Preserved Architecture Versus Abandoned Locations in Film Production

Production companies choosing Delaware filming locations prioritize intact historical architecture over decayed structures, reversing the ghost town appeal found in Western film markets. You’ll find *Dead Poets Society* utilized St. Andrew’s School’s Gothic Revival buildings without modifications. Meanwhile, *Beloved* captured New Castle’s 1700s cobblestone streets immediately, eliminating set construction delays.

Natural landscapes at Lewes beaches and Fort Miles offer WWII ruins, yet no productions documented their use—filmmakers consistently select preserved sites over abandoned alternatives. This preference stems from logistical advantages: existing structures provide immediate backdrops, reducing budget constraints and permitting complications.

Modern infrastructure surrounding New Castle’s historic district and Wilmington’s urban settings enables rapid crew access, equipment transport, and year-round shooting schedules. Delaware’s hundreds of abandoned locations remain unused, proving maintained architecture outweighs atmospheric decay for production efficiency.

Regional Confusion: Pennsylvania Ghost Towns Often Mistaken for Delaware

Geographic proximity to Pennsylvania creates persistent misidentification of ghost town locations, with Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area serving as the primary confusion point. You’ll find YouTube videos and Atlas Obscura listings incorrectly attributing Pennsylvania’s Minisink Valley ghost towns—Bevans, Layton, Walpack—to Delaware.

Border confusion at Delaware Water Gap leads online sources to routinely misplace Pennsylvania ghost towns into Delaware territory.

The shared Delaware River border fuels these urban legends, particularly when Tocks Island Dam project narratives blur state lines. Eckley Miners’ Village, preserved through Sean Connery’s filming, stands in Pennsylvania near the border yet appears in Delaware ghost town compilations.

Historic myths perpetuate through media misattribution: Pennsylvania’s Centralia, Frick’s Lock, and abandoned Turnpike sections get grouped into mid-Atlantic ghost narratives without state distinction.

You’re encountering deliberate regional marketing that conflates Delaware’s name recognition with Pennsylvania’s actual abandoned sites.

How Delaware’s Active Historic Sites Attract Location Scouts

When location scouts search for authentic period settings, they’ll prioritize sites offering preserved architecture over CGI-dependent alternatives. Delaware’s active historic properties deliver standing 18th-century structures within two hours of Philadelphia and Baltimore production hubs.

Amstel House provides untouched colonial interiors, while Bellevue Hall‘s grand manor aesthetic eliminates construction costs.

Fort Delaware’s Civil War-era masonry on Pea Patch Island offers island isolation without permit complications plaguing urban decay locations.

Historical preservation regulations protect these sites while permitting commercial filming. You’ll navigate clearer contracts than abandoned properties lacking ownership documentation.

Fort DuPont’s 80 remaining structures from its 300-building peak provide diverse backdrops within single locations.

Scouts appreciate Delaware’s compact geography: multiple period-correct sites exist within a 30-mile radius, reducing transportation budgets while maintaining visual continuity across shooting schedules.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Permits Are Required to Film in Delaware’s Historic Districts?

You’ll need a Historic Review Certificate from local commissions before filming in Delaware’s historic districts. Permit regulations guarantee historical preservation while protecting resources. Submit applications early, provide insurance proof, and notify nearby residents per district requirements.

How Much Does It Cost to Rent Filming Locations in Delaware?

Specific rental costs for Delaware filming locations aren’t publicly available. You’ll need to contact property owners directly and secure film permits through local municipalities, especially when working in historic districts where fees vary by location and production scope.

Which Delaware Tax Incentives Attract Film Production Companies?

Delaware’s new 30% transferable tax credit attracts productions through location subsidies capped at $1 million per project. You’ll access these tax incentives with minimum $100,000 spend, covering commercials through features while maintaining creative control.

Can Independent Filmmakers Access the Same Delaware Locations as Major Studios?

Yes, you’ll access Delaware’s studio-proven locations independently. Secure permits through local districts, coordinate your remote crew logistics, and arrange equipment rental from Wilmington vendors. Historic sites, beaches, and urban backdrops welcome your production scale equally.

What Time Periods Can Delaware’s Architecture Authentically Represent on Film?

You’ll find Delaware’s architectural styles authentically represent 1700s colonial through contemporary 2020s periods with historical accuracy. Colonial districts, 1950s Gothic Revival campuses, and modern urban landscapes let you capture any era between pre-Revolutionary America and today’s settings.

References

- https://www.worldatlas.com/cities/4-delaware-towns-where-famous-movies-were-filmed.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwOoDhWFvTI

- https://goosebumps.fandom.com/wiki/Madison

- https://www.farmweddingde.com/wedding-blog/haunted-history-in-delaware-city-tourism-in-the-first-state

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Films_shot_in_Delaware

- https://www.latlong.net/location/dead-poets-society-locations-176

- https://www.sceen-it.com/sceen/3354/Dead-Poets-Society/St-Andrew-s-School

- https://movie-locations.com/movies/d/Dead-Poets-Society.php

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWll2sdmAYw

- https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/DE-01-LN19