You won’t find authentic Great Plains ghost towns in classic Westerns like *High Plains Drifter*—filmmakers consistently bypassed historically accurate prairie landscapes for California and Nevada’s dramatic terrain. Eastwood scouted 300 miles from Hollywood, choosing Mono Lake’s rocky southern shore over flat Texas or Dakota plains. His crew built Lago from scratch in 18 days using 150,000 feet of lumber, creating 14 fully functional structures painted with 380 gallons of red paint. The production wrapped two days early, then dismantled everything. The following details reveal why Hollywood prioritized visual impact over geographic authenticity.

Key Takeaways

- Great Plains locations like Texas High Plains and South Dakota provide expansive flat vistas ideal for recreating large Western settlements.

- Central Plains terrain supports period-specific sets with easier management of extras and uniform sunlight for consistent filming conditions.

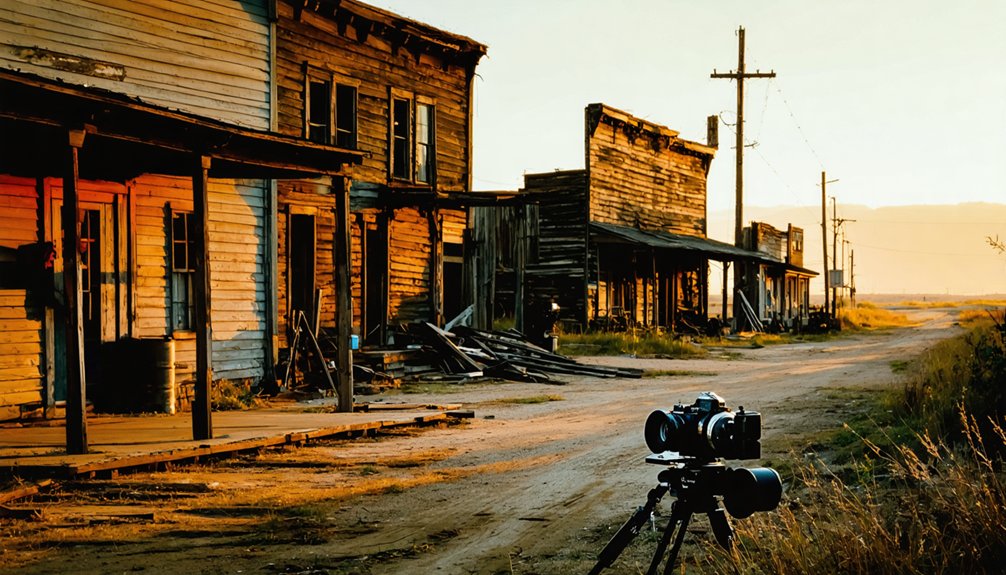

- Plains ghost towns offer authentic structures that reduce construction needs while maintaining historical accuracy for Western film atmospheres.

- Flat terrain facilitates efficient set relocation and accommodates large crowds necessary for recreating frontier town scenes.

- Great Plains sites enable dynamic horizon lines and open landscapes that enhance traditional Western cinematography and storytelling.

The Iconic Filming Location of High Plains Drifter

When Clint Eastwood scouted filming locations across Oregon, Nevada, and California in a pickup truck, he ultimately chose Mono Lake’s southern shore for its stark, photogenic qualities that would amplify the film’s vengeance narrative.

You’ll find the coordinates at 37°56’42.5″N 119°02’26.9″W, where 150,000 feet of lumber built fourteen houses, a church, and a two-story hotel in just eighteen days. The crew constructed full three-dimensional structures rather than facades, enabling complete interior filming freedom. However, historical preservation wasn’t prioritized—no structures survive today.

The production’s environmental impact remains minimal since everything was dismantled post-filming. The entire set was transformed using 380 gallons of paint to achieve the town’s fiery red exterior, symbolizing the film’s themes of retribution and moral reckoning. Near Lee Vining off CA-120, the site showcases Mono Lake’s distinctive tufa formations, offering unrestricted exploration of where cinema transformed California’s wild landscape into an unforgettable Western backdrop. Eastwood completed the six-week production ahead of schedule, finishing two days early and under budget.

Why Mono Lake Was Chosen Over Authentic Great Plains Landscapes

Clint Eastwood’s decision to bypass authentic Great Plains ghost towns in favor of Mono Lake’s California shores hinged on practical filmmaking realities rather than geographical authenticity. You’ll find the location delivered unmatched logistical advantages—120 miles from Lone Pine, accessible via I-395, with minimal environmental impact from temporary construction.

The crew erected 14 structures using 150,000 feet of lumber in just 18 days, finishing two days early. Mono Lake’s cultural significance as a cinematic landscape outweighed Plains authenticity, offering ethereal tufa formations that enhanced the film’s vengeance themes.

The remote basin provided visual flexibility unavailable in flat grasslands, letting Eastwood craft controlled, otherworldly compositions. The Sierra Nevada Mountains backdrop added dramatic peaks ranging from 11,000 to 14,000 feet that flat prairie landscapes couldn’t replicate. Proximity to Los Angeles cut transportation costs while the vast, empty terrain accommodated on-location interiors Universal’s backlot couldn’t match. The emphasis on nature’s raw beauty over studio sets created an immersive experience that shaped the film’s storytelling tone and timeless atmosphere.

Building the Town of Lago From Scratch in 18 Days

You’ll find that over 50 technicians and construction workers transformed 150,000 feet of lumber into a complete frontier town within just 18 days on Mono Lake’s southern shore.

They constructed 14 full houses, one church, and a two-story hotel—not hollow facades, but structurally sound buildings with finished interiors that could accommodate cameras and crew for interior shooting.

This wasn’t set dressing; it was authentic construction at breakneck speed, with every wall, floor, and ceiling built to withstand the demands of a six-week production schedule. The rocky and barren terrain of Mono County provided a stark contrast to the traditional grassland scenery typically associated with Western films.

The set layout featured key buildings positioned strategically, with the hotel and barber shop placed to the left and right respectively as visitors would enter the town.

Massive Labor and Materials

Before a single frame could be shot, Eastwood’s production team faced an extraordinary construction challenge: building an entire Western town from scratch on the remote southern shores of Mono Lake.

You’re looking at a massive operation requiring over 50 technicians and construction workers who hauled 150,000 feet of lumber to coordinates 37°56’42.5″N 119°02’26.9″W.

Construction logistics demanded transporting materials, catering wagons, and equipment across eastern Sierra Nevada terrain to an isolated site.

Labor force management proved critical as crews erected 14 houses, a church, and a two-story hotel in just 18 days.

The mock town included a barber shop and general store among its structures, creating an authentic Western settlement.

The cast and crew initially painted structures fiery red using 380 gallons of paint before professionals finished the job.

This joint Malpaso-Universal production came in under budget despite the scale and remoteness.

Eastwood’s decision to use real landscapes over studio sets provided the authenticity that became central to the film’s gritty tone.

Complete Buildings, Not Facades

Unlike most Hollywood Western sets that relied on false-front facades propped up by wooden braces, Eastwood’s production crew constructed fourteen fully functional houses with working interiors, complete walls, and authentic roofing systems.

This architectural authenticity freed you from studio constraints—cameras could move seamlessly between exterior and interior shots without relocating to soundstages. The set design included a two-story hotel and a church, each built as complete structures rather than theatrical illusions.

You’ll find this approach eliminated the typical boundaries of Western filmmaking. Crews could shoot 360-degree angles, actors could inhabit genuine spaces, and the entire production gained mobility.

The buildings’ structural integrity supported the six-week shoot, which wrapped two days ahead of schedule—proof that authentic construction accelerates rather than hinders creative freedom. After filming concluded, the town of Lago was dismantled, leaving the site as a bare desert patch that still evokes the authentic Western atmosphere it once represented.

Rapid Construction Timeline

When Eastwood’s crew arrived at Mono Lake’s desolate shoreline in early 1972, they faced an 18-day deadline to transform barren terrain into the fully functional Western town of Lago.

You’d witness over 50 technicians and laborers tackling massive logistical challenges, hauling 150,000 feet of lumber across 300 miles of California wilderness. The set design demanded complete buildings—14 houses, a two-story hotel, and a church—all with working interiors for on-site filming.

Workers then drenched every structure in 380 gallons of fiery red paint, creating the film’s signature visual impact. The location along Mono Lake’s southern shore provided the dramatic backdrop of salt-encrusted waters and limestone tufa towers that enhanced the film’s dreamlike atmosphere. This breakneck construction schedule supported the six-week filming timeline, ultimately finishing two days early.

No corporate red tape, no bureaucratic delays—just raw determination building a town where none existed before.

Contrasting Terrain: Rocky California Versus Flat Great Plains

The physical geography separating California’s ghost town filming sites from Great Plains locations creates fundamentally different production challenges and visual possibilities. California’s Eastern Sierra offers dramatic vertical relief—Mono Lake’s alkaline shores, Alabama Hills’ eroded boulders, and Cerro Gordo’s steep mining roads demand ATV access while rewarding you with stunning elevation contrasts.

California’s mountainous ghost towns require specialized vehicle access but deliver the dramatic elevation changes impossible to replicate on level plains.

You’ll find landscape manipulation simpler on Texas High Plains and South Dakota prairies, where flat expanses accommodate large extras crowds, period building relocations, and driveable access roads.

This terrain diversity shapes lighting conditions: Sierra canyons create dynamic shadows for chase sequences, while uniform plains sunlight delivers endless horizontal horizons.

When you’re constructing authentic Western sets, mountainous sites like Telluride‘s rocky outcrops enhance dramatic tension.

In contrast, level Colorado flats near Greeley facilitate expansive settlement recreations with minimal logistical constraints.

Secondary Filming Sites Across Nevada and California

Nevada’s desert ghost towns offer production teams immediate access to layered filming environments where authentic historical structures merge with decades of accumulated film props.

You’ll find Nelson Ghost Town maintains an exploded airplane from *3,000 Miles to Graceland*, surrounded by desert vegetation and weathered structures that embed local folklore into every frame.

The Techatticup Mine and Eldorado Canyon provide documented outlaw history, eliminating fictional backstory requirements.

Gold Point’s central Nevada location serves documentary productions exploring authentic haunted narratives.

California’s High Sierra presents contrasting alpine environments—Fallen Leaf Lake’s Tallac House hosted *The Bodyguard* filming, while Highway 89 near Emerald Bay captured intimate character moments.

Silver City maintains active registration with multiple film commissions, ensuring scout network visibility for productions requiring accessible, catalog-ready ghost town backdrops.

Clint Eastwood’s Location Scouting Process

You’ll find Eastwood rejected Universal’s ready-made backlots and instead drove his pickup truck solo across Nevada, Oregon, and California to scout locations firsthand. His reconnaissance prioritized sites 300 miles from Hollywood.

Ultimately, he identified Mono Lake’s soda-crusted shores as the ideal setting for building Lago from scratch. The director’s assessment required evaluating each location’s visual authenticity, construction feasibility, and logistical accessibility before committing to the project.

The build took 18 days and involved constructing fourteen structures plus a two-story hotel and a church.

Solo Scouting by Truck

Clint Eastwood’s truck-based scouting method strips location hunting down to its essentials: one director, one vehicle, and miles of unfiltered terrain assessment. You’ll find him steering Interstate 94 corridors and rural backroads solo, bypassing digital mapping and aerial surveys that distance filmmakers from ground truth.

His truck becomes a mobile command center evaluating whether ghost town ruins accommodate camera dollies and grip trucks before they’re beautiful. Between Augusta’s Central Avenue and Michigan’s veteran routes, he’s confirming asphalt integrity and sight lines—logistics that determine if a visually perfect abandoned Plains settlement remains practical.

This autonomy preserves confidentiality while letting him pivot instantly when a desolate stretch of Oregon’s Treasure Valley or White Sands’ rugged isolation matches his production designer’s Western aesthetic without crew constraints.

Rejecting Universal’s Backlot

Why would a director with guaranteed studio access abandon controlled backlot environments for unpredictable Plains locations? You’d understand if you’d experienced Universal’s restrictions firsthand.

Studio sets meant film censorship through executive oversight, constant interference in creative decisions, and casting controversies that derailed authentic visions. Eastwood recognized backlots couldn’t replicate the weathered grain elevators, crumbling homesteads, and wind-carved storefronts that real ghost towns offered.

These abandoned settlements provided textural authenticity no soundstage could manufacture—peeling paint revealing decades of prairie sun, floorboards sagging under genuine structural decay, horizons stretching uninterrupted for miles.

Selecting Mono Lake Location

Two months before cameras rolled, Eastwood loaded his pickup truck and drove solo through Nevada, Oregon, and California’s eastern spine. He’d rejected conventional Western plains, seeking terrain contrast that matched his vision.

At Mono Lake’s southern shore off CA-120, he found it—a saline soda lake where tufa towers rose like skeletal fingers from alkaline waters. The desolate canvas offered exactly what Lago reconstruction demanded: haunting emptiness 300 miles from Hollywood’s constraints.

Walking the shoreline, Eastwood marked three boulders behind today’s scenic viewpoint, noting a fallen log and wood barrier. The coordinates 37°56’42.5″N 119°02’26.9″W became his construction zone.

That 1970s access road, now vanished, brought equipment down from the 1,000-foot-high viewpoint near Lee Vining for complete on-location interiors.

The Complete Construction Method and Its Impact on Filming

When production crews needed to transform remote locations into convincing Old West settlements, they employed three distinct construction approaches that fundamentally shaped filming logistics.

1. Rapid Custom Constructions: You’d witness 50 technicians assembling complete towns in 18 days using 150,000 feet of lumber, constructing full interiors beyond false fronts for seamless interior-exterior transitions that eliminated transportation delays.

2. Authentic Relocations: Crews physically moved abandoned prairie structures from real ghost towns, reassembling them roadside to achieve unmatched historical authenticity.

They also integrated purchased props like *Dances with Wolves* teepees for enhanced period accuracy.

3. Direct Repurposing: Production teams capitalized on existing mining communities’ original wooden storefronts and poplar-lined streets, applying minimal modifications to preserve construction technology and atmospheric textures.

These methods optimized your production schedules while delivering the visual freedom remote landscapes demanded.

What Happened to the Movie Set After Production Wrapped

Production crews faced drastically different post-filming scenarios depending on whether they’d built temporary sets or utilized existing ghost towns. You’ll find that Big Country’s one-street construction didn’t vanish into thin air—workers dismantled it and trucked everything to Pollardville’s tourist attraction, where these film relics stood until 2010’s demolition.

The High Plains Drifter team assembled Lago’s 14 buildings using 150,000 feet of lumber in just 18 days, though their current fate remains undocumented. Meanwhile, Bodie ghost town required zero demolition since it was already standing—you’re free to visit this preserved mining hub today.

Groom, Texas transformed into Rustwater with temporary storefronts, but restoration records haven’t surfaced. Most abandoned towns either absorbed or erased these Hollywood footprints entirely.

The Film’s Accelerated Production Timeline and Budget Success

You’ll find that *High Plains Drifter* wrapped its entire six-week filming schedule ahead of its projected timeline, thanks to the 18-day Mono Lake set construction that put cameras rolling faster than typical western productions.

The budget stayed under its $5.5 million allocation because Eastwood’s pickup truck location scouting eliminated expensive aerial surveys. The 50-person construction crew built all 14 buildings, the church, and two-story hotel without overtime delays.

This accelerated approach meant no weather-related overruns, no extended crew lodging costs, and immediate filming integration with the Sierra Nevada backdrop once hammers stopped swinging.

Six-Week Filming Completion

Three factors accelerated completion:

- 1880 Town’s salvaged buildings eliminated weeks of carpentry work, providing instant Western storefronts.

- Regional clustering across South Dakota and Alberta sites reduced crew relocation downtime between shoots.

- On-site buffalo herds at nearby Turner ranches removed animal transport complications.

You’re witnessing efficiency born from respecting what’s already there—abandoned structures reborn without bureaucratic delays.

Ahead of Schedule Finish

When pre-production concludes two weeks early, you’re already banking time that compounds through every subsequent phase. Your settled locations and confirmed cast availability let you experiment with lighting techniques that’d normally get scrapped under pressure.

Buffer times in your shooting schedule absorb technical delays without bleeding into contingency days. The First AD’s disciplined timeline management keeps complex camera angles from ballooning setup hours.

Your equipment lists prevent wasteful downtime, while shot lists refined during those extra pre-production weeks eliminate guesswork on set. Day-out-of-days tracking ensures you’re not paying idle actors.

When the final cut emerges three days ahead of deadline, it’s not luck—it’s front-loaded efficiency materializing exactly as planned, leaving budget surplus intact.

Under Budget Achievement

2. Environmental impact minimized: Groom, Texas was transformed into Rustwater using temporary tent revivals and facades. This approach left the landscapes undisturbed.

3. Local infrastructure leveraged: Claude’s small-town buildings and Amarillo’s Barfield Hotel basement required zero modifications for period-authentic scenes.

Historic Landmarks Near the Filming Locations

Beyond the film sets themselves, each ghost town location sits within reach of significant historical sites that shaped the regions long before cameras arrived. You’ll find Mark Twain’s 1861 island stranding at Mono Lake documented in “Roughing It,” predating Clint Eastwood’s “Lago” set by over a century.

Near Ghost River, Alberta’s Rocky Mountain front ranges offer trails connecting Calgary to Canmore—paths carved long before World War I trench scenes appeared in Legends of the Fall. While lacking Medieval architecture or modern urban development, these prairie and mountain landscapes preserve authentic frontier history.

The Cerro Gordo mining district near Lone Pine reveals California’s silver rush era, with Alabama Hills‘ natural formations serving countless Westerns since the 1920s.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Actual Ghost Towns From the Great Plains Used in Filming?

You’d think Hollywood would embrace authentic Great Plains ghost towns for historical preservation and local economic impact, but they haven’t. Filmmakers built sets or chose safer locations instead, bypassing real abandoned towns despite their visual authenticity and freedom from modern intrusions.

How Did Locals React to the Film Production Near Mono Lake?

The background information doesn’t document local reactions to the Mono Lake production. You’ll find details about construction scale and regional film history, but specific community responses regarding local economic impact or community preservation concerns aren’t recorded here.

What Other Western Films Have Been Shot at Mono Lake?

Mono Lake’s film history includes four major Westerns beyond High Plains Drifter: True Grit, Nevada Smith, and North to Alaska all captured its stark desert landscapes. You’ll find these productions chose freedom in remote locations over studio constraints.

Can Visitors Access the Original Filming Location at Mono Lake Today?

You can access the original filming location at Mono Lake’s shore today without filming permits, though tourist access requires four-wheel drive vehicles. Nothing remains of the Lago set, but you’re free to explore the atmospheric tufa-studded terrain.

Did the Cast and Crew Stay in Lee Vining During Production?

You’d think production records would chronicle every detail about lighting techniques and costume design logistics, but there’s absolutely no documented evidence confirming the cast and crew actually stayed in Lee Vining during filming at Mono Lake.

References

- https://giggster.com/guide/movie-location/where-was-high-plains-drifter-filmed

- https://screenrant.com/where-was-high-plains-drifter-filmed/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3_SutYarWg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Plains_Drifter

- https://movie-locations.com/movies/h/High-Plains-Drifter.php

- https://epicalab.com/where-was-high-plains-drifter-movie-filmed/

- http://the-great-silence.blogspot.com/2008/10/high-plains-drifter-location-at-mono.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VbpQEWL1_rg

- https://travelnoire.com/where-was-high-plains-drifter-filmed

- https://www.oreateai.com/blog/exploring-the-filming-locations-of-high-plains-drifter/f8aa932d0a55440642ba02f7d3c577ec