Girard, California was Victor Kleinberger’s 1920s real estate scheme in the San Fernando Valley. You’d have seen Moorish-themed facades, false-front businesses, and thousands of hastily planted pepper trees creating an elaborate Mediterranean mirage. When the 1929 stock market crashed, the development collapsed, transforming from hundreds of residents to mere dozens by 1932. Unlike many ghost towns, Girard evolved into modern Woodland Hills, though traces of its theatrical past still linger beneath the suburban landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Girard was a speculative real estate development in San Fernando Valley founded by Victor Girard Kleinberger in 1922.

- After the 1929 stock market crash, Girard rapidly declined, with its population dropping from hundreds to dozens by 1932.

- The development featured false-fronted buildings creating an illusion of a thriving business district to deceive potential buyers.

- Girard used deceptive marketing tactics like “sucker buses” and fake amenities to sell small parcels to distant buyers.

- The failed town was later revitalized and renamed Woodland Hills in 1941, transforming from a ghost town into a thriving community.

The Visionary Swindler: Victor Girard’s Grand Plan

While peddling fake Persian rugs door-to-door and feigning tuberculosis to keep potential customers from closing their doors, Victor Girard Kleinberger was perfecting the deceptive sales techniques that would later transform cow pastures into a short-lived real estate empire.

Dropping “Kleinberger” to craft a marketable persona, Girard deployed visionary tactics when he acquired 2,886 acres of San Fernando Valley land in 1922.

Through his Boulevard Land Company, he subdivided agricultural properties into 6,828 small lots—a radical departure from the Valley’s typical 80-acre parcels.

Carving up expansive farmland into thousands of tiny plots—Girard’s first step in transforming agricultural wasteland into profitable fantasies.

His swindle strategies included Moorish-themed architecture, manufactured community amenities, and aggressive marketing to distant Midwestern and Eastern buyers who couldn’t inspect properties before purchase.

You’d recognize his genius in creating the illusion of legitimacy—schools, newspapers, and fire departments—all while hiding financial obligations that would ultimately trap unsuspecting settlers. Girard’s prior development success in West Adams had bolstered his reputation, making his ambitious Valley project seem more credible to potential investors.

He frequently loaded potential buyers onto sucker buses that transported them to his carefully staged development sites, complete with false storefront facades designed to create an illusion of established prosperity.

A Mirage in the San Fernando Valley: Marketing a Fantasy

Imagine attending one of Victor Girard’s moonlight desert soirees where you’d be served exotic refreshments while salesmen whispered promises of wealth into your enthusiastic ears.

You’d marvel at the manufactured Mediterranean oasis with its Turkish-inspired facades and newly planted trees—all carefully staged to hide the parched reality of this San Fernando Valley outpost. Girard’s innovative selling techniques included his infamous sucker buses that transported potential buyers to view properties. The town originally called Gerard was later renamed to Woodland Hills in 1941, erasing much of its questionable origins from public memory.

What you couldn’t see were the empty promises being sold: ocean breezes that couldn’t penetrate mountain ranges, reservoir waters that never flowed, and paper deeds to lots that might’ve been sold fifty times over.

Moonlight Desert Soirees

As the San Fernando Valley shifted from agricultural heartland to sprawling suburb in the mid-twentieth century, enterprising developers and promoters concocted a seductive marketing fantasy known as “Moonlight Desert Soirees.”

These elaborate nighttime gatherings never actually existed in Girard’s brief history, yet they became part of the area’s mythmaking—a fabricated tradition invented to sell an idealized desert lifestyle to prospective homebuyers and tourists. Much like Samuel’s abandoned stories marked as up for adoption, these fictional events were created but never truly realized as intended.

You’d have seen these desert escapism dreams vividly depicted in promotional materials—moonlit parties where urban professionals could escape LA’s congestion for starlit cocktails and exclusive gatherings in the valley’s undeveloped stretches. Similar to the popular Moon Walks at Prime Desert Woodland Preserve that offer authentic nighttime desert experiences today, these fictional soirees promised magical evening encounters with nature.

The imaginary events leveraged California’s romanticized desert mystique, promising transformative experiences just a short drive from the city.

These fictional soirees became powerful marketing tools, turning barren land into canvases for projected fantasies of freedom and luxury.

Manufactured Mediterranean Oasis

The fabricated Moonlight Desert Soirees weren’t the only fantasy peddled to would-be San Fernando Valley residents—they were merely one act in a larger spectacle of illusion.

Victor Girard conjured a Mediterranean mirage amid rural pastures, promising a Moorish-themed paradise where Southern California’s fascination with exotic locales would find satisfaction.

You’d have discovered curved streets lined with promised trees, but little substance behind the façade. Those miniature lots—often purchased sight unseen—barely accommodated the shoddily constructed cabins that replaced the elegant villas in glossy brochures.

The celebrated nursery existed, but the Mediterranean oasis remained firmly on paper.

Behind this theater of development, Girard’s Boulevard Land Company buried buyers in hidden infrastructure costs while building a town of false-fronted structures—a cardboard fantasy that would collapse under the weight of lawsuits, market crashes, and broken promises, reminiscent of how Ohio became state in 1803 while Girard, Ohio was still being settled.

Empty Promises Sold

Marketing materials for Girard, California, depicted a paradise that never fully materialized. You’d have been shown glossy brochures of Mediterranean villas nestled among lush greenery—a promised paradise just a short drive from Los Angeles.

Victor Girard’s salesmen painted deceptive dreams of a self-contained community where city-dwellers could escape to country comfort.

What they didn’t tell you:

- Lots were often too small for actual construction

- “Low prices” excluded hidden infrastructure costs

- Many amenities existed only in brochures

- Cabins were hastily constructed with subpar materials

- The Mediterranean oasis required constant maintenance you’d fund

The reality buyers discovered was starkly different—barren plots in undeveloped land, unexpected fees, and incomplete facilities.

Your dream home would become a financial nightmare as Girard’s promises evaporated into the San Fernando Valley heat.

Behind the Moorish Facades: The Reality of Girard’s Community

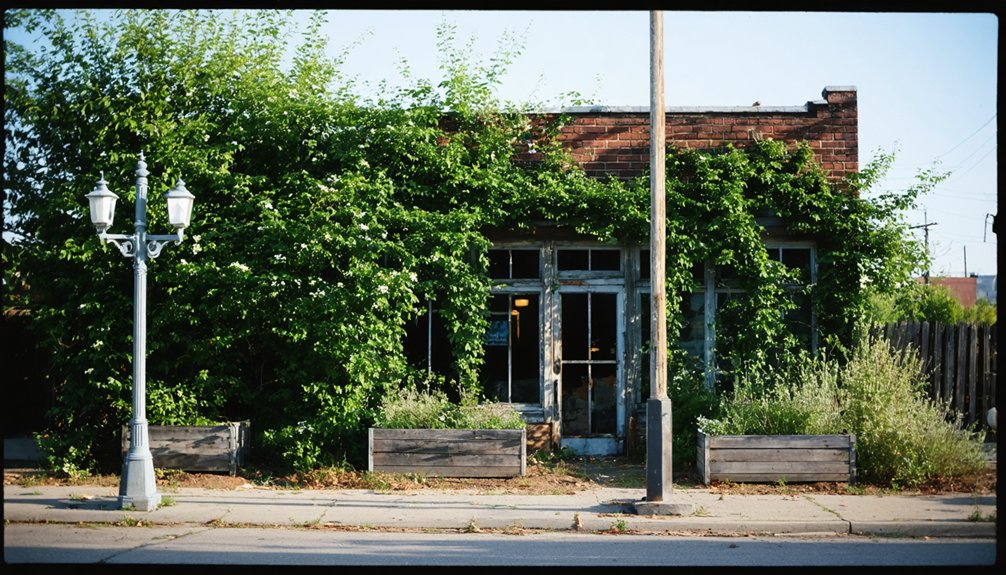

Behind Girard’s ornate Moorish facades and towering minarets lay a stark contrast between fantasy and reality that defined this ambitious California development.

The town center’s elaborate Moorish Architecture at Topanga Canyon and Ventura Boulevards was merely an illusion—false storefronts with no actual businesses inside. These empty shells, deliberately distinct from popular Mission style, served only to entice potential buyers into Community Illusions of grandeur.

Meanwhile, reality took shape in 100-120 spartan cabins scattered throughout the Girard Tract. The area was eventually annexed to Los Angeles in 1917, following the pattern of neighboring communities like Owensmouth that faced similar water supply challenges. Most lacked basic amenities like running water and electricity despite the minimum 500-square-foot requirement. After the stock market crash of 1929, land speculation and sales came to an abrupt halt, further impeding development.

A devastating fire in the late 1920s destroyed many original structures, leaving only about a dozen survivors that have since been extensively remodeled.

Today’s Woodland Hills bears little resemblance to Girard’s grand vision, save for his legacy of 120,000 trees.

The Boulevard Land Company’s House of Cards

With a foundation built entirely on deception, Victor Girard Kleinberger’s Boulevard Land Company engineered one of Southern California’s most brazen real estate schemes in 1922.

After the land acquisition of 2,886 acres from Harry Chandler’s syndicate, they subdivided it into over 6,000 tiny lots—a stark contrast to the typical 80-acre Valley parcels.

Their marketing tactics included:

- Erecting false-fronted buildings to simulate a thriving business district

- Planting thousands of trees throughout barren land

- Building ornate Moorish-themed gates and towers

- Advertising aggressively in newspapers

- Selling the illusion of “small hillside country estates”

The company’s development radically transformed what had previously been fertile agricultural land that once served as Los Angeles’ breadbasket.

You wouldn’t discover until too late that some parcels were sold multiple times with hidden liens attached.

From Boom to Bust: How the 1929 Crash Sealed Girard’s Fate

You’ve probably heard about ghost towns born from dried-up gold mines or abandoned rail stops, but Girard’s demise came from something more insidious: the sudden collapse of speculative finance.

When Wall Street crashed in October 1929, the already-teetering house of cards that Victor Girard had built came tumbling down with startling speed, revealing that much of the town’s apparent prosperity had been merely financial illusion.

Within months, residents began an exodus that would reduce the population from hundreds to mere dozens by 1932, leaving behind half-built dreams and mortgage papers worth less than the wood they’d been printed on.

Market Crash’s Immediate Impact

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, the fragile economic foundations of Girard, California crumbled almost overnight.

Victor Girard’s grand vision collapsed as investors withdrew and settlers faced devastating personal financial losses. The crash revealed his land schemes as largely fraudulent, triggering waves of community disillusionment.

The economic despair manifested in multiple ways:

- Property values plummeted below purchase prices

- The Boulevard Land Company’s land became unsellable

- Heavy taxation continued on increasingly worthless parcels

- Legal challenges drained remaining resources

- Infrastructure maintenance ceased almost immediately

Financial Illusions Exposed

The elaborate financial mirage constructed by Victor Girard and his Boulevard Land Company dissolved under the harsh light of economic reality following the 1929 crash.

What you weren’t told when purchasing your dream lot was that it came encumbered with substantial liens for infrastructure improvements—debts you’d be legally obligated to repay.

This lack of financial literacy proved devastating as the agricultural San Fernando Valley couldn’t support the speculative investments Girard had promoted through his glossy newsletters and grand promises.

Your property values plummeted while debt obligations remained, exposing the fundamental disconnect between promotional fantasies and economic fundamentals.

The subdivision’s appeal had rested not on sustainable commercial development or industrial growth, but on an artificially inflated real estate bubble.

When credit markets tightened, you couldn’t refinance the loans on properties suddenly worth a fraction of their purchase price.

Final Exodus Unfolds

Black Tuesday’s thunderous impact on Wall Street reverberated through Girard with devastating consequences, triggering the community’s rapid disintegration. The final exodus began almost immediately after the crash, with residents fleeing financial ruin and broken promises.

By 1932, you’d find only 75 families where hundreds once lived—a stark indication of community collapse.

As families departed, they left behind:

- Abandoned cabins deteriorating into the landscape

- Unpaid tax bills piling up at the county office

- Empty storefronts where businesses once thrived

- Silent streets stripped of neighborly sounds

- Overgrown lots reclaiming Victor Girard’s manicured vision

The exodus transformed Girard from a bustling development to a near-ghost town in just three years—victims of both national economic forces and local deception that left them no choice but abandonment.

The Ghost Town That Never Quite Died

Unlike most ghost towns that completely vanish into the California desert, Girard clung to life despite its spectacular collapse as a real estate scheme. By 1932, only 75 families remained, surviving among the empty streets and abandoned dreams of what was once promoted as a Moorish paradise.

In the skeleton of Girard’s grandiose vision, resilient families forged lives amid vacant boulevards and faded Moorish fantasies.

While Victor Girard fled and his Boulevard Land Company crumbled under lawsuits and debt, these resilient few weathered the Great Depression in this speculative venture’s shell.

In 1941, they officially broke with their troubled past, voting to rename the community Woodland Hills—a nod to the thousands of trees that outlasted their planter’s grand deception.

You can still walk these curving streets today, though little evidence remains of the ghost town that refused to disappear completely.

Woodland Hills Rising: How Residents Reclaimed Their Community

After years of living in the shadow of Girard’s failed real estate dreams, residents took their community’s fate into their own hands in 1941 by forming a chamber of commerce with a transformative mission.

They officially renamed the area Woodland Hills, a strategic move that galvanized neighborhood cohesion and established a fresh community identity.

What began as 75 families in the 1930s blossomed into a thriving community of 4,500 by 1950, with residents united by:

- Tree-lined streets featuring 120,000 planted trees

- Well-planned residential developments blending with natural hillsides

- Shift from agricultural land to diverse economic sectors

- Preservation of natural contours and scenic views

- Strategic development of Warner Center as a commercial hub

You’re witnessing not just a renamed town, but a complete reinvention—locals transforming Girard’s ghost into Woodland Hills’ reality.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Celebrities or Notable Figures Residents of Girard?

Frankly, famous faces were few in Girard. You won’t find any celebrity sightings or notable residents during the town’s brief existence—research reveals only about 75 ordinary families remained by 1932.

What Happened to Victor Girard After the Town’s Collapse?

After Girard’s town collapsed, you’d find Victor lived until 1954, witnessing Woodland Hills’ growth from afar. His legacy remained controversial, with locals erasing his name while he watched his vision transform without him.

Are Any Original Girard Buildings Still Standing Today?

You won’t find any original structures from Girard standing today. Unlike other ghost towns with historical preservation efforts, Girard’s false storefronts and Moorish buildings were absorbed into modern Woodland Hills without a trace.

Did Girard Have Its Own Unique Architectural Style?

Like a Turkish mirage in California’s desert, Girard’s architecture blossomed with distinctive Moorish-themed buildings and towers. You’d recognize this unique style that deliberately contrasted with Mission influences, creating an exotic architectural identity all its own.

How Did Local Native American Communities View Girard’s Development?

You won’t find recorded indigenous perceptions of Girard specifically, as Native Americans had already faced displacement and cultural impact long before its 1922 development through colonial and state policies.

References

- https://valleyrelicsmuseum.org/general-museum-news/valley-relics-early-history-scandals-of-the-1920s/

- https://la.curbed.com/2014/4/16/10115040/how-a-visionary-scoundrel-created-woodland-hills-in-the-1920s

- https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/tv/a33079270/perry-mason-episode-3-girard-meaning-true-story-woodland-hills/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PgJVpp0aSBI

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.inletny.com/story/2015/08/ouida-girard

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=65944

- https://www.thetravel.com/california-gold-rush-town-underrated-adventure-destination/

- https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-feb-10-re-guide10-story.html

- https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll2/id/19429/