You’ll discover Golden, New Mexico along State Road 14’s Turquoise Trail, where America’s first gold rush west of the Mississippi began in 1825. Two mining camps merged by 1839 to form this historic settlement, blending Native American, Spanish colonial, and American mining heritage. Today, this semi-ghost town of 21 residents features the restored San Francisco Catholic Church, Henderson Store ruins, and remnants of its mining heyday. The story of Golden’s rise and fall holds countless treasures for history enthusiasts.

Key Takeaways

- Golden is a semi-ghost town in New Mexico with only 21 residents, featuring remnants of America’s first gold rush west of Mississippi.

- The restored San Francisco Catholic Church, founded in 1839, stands as the town’s most prominent preserved historical structure.

- Visitors can explore mining remnants, Henderson Store ruins, and historic buildings along New Mexico State Road 14.

- The town emerged from two mining camps that merged in 1839, following gold discoveries along Tuerto Creek in 1825.

- Located along the Turquoise Trail Scenic Byway, Golden offers authentic ghost town exploration with no modern amenities or facilities.

The First Gold Rush West of the Mississippi

While most Americans associate the nation’s first major gold rush with California in 1849, the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828 by Benjamin Parks actually marked America’s initial significant gold rush.

When Parks stumbled upon a large gold-bearing rock, you’d have witnessed a swift transformation of the region as 15,000 miners flooded the area within just one year.

The early mining techniques were relatively simple, as much of the gold lay near or on the surface. The Consolidated Gold Mine became the largest mining operation east of the Mississippi River.

You’ll find it interesting that French explorers had documented Native Americans panning for gold in the Appalachians as early as 1564.

The cultural influence of this rush was immediate and lasting, establishing boomtowns like Auraria and Dahlonega while forever changing the demographic makeup of northern Georgia.

Like many who joined the California Gold Rush, most miners faced harsh conditions and returned home with little to no gold.

Birth of a Mining Town: 1825-1839

You’ll find Golden’s origins in the first gold rush west of the Mississippi, predating both California’s and Colorado’s famous discoveries when gold was found on Tuerto Creek in 1825.

Two distinct mining camps, El Real de San Francisco and Placer del Tuerto, emerged on the southwest side of the Ortiz Mountains as prospectors sought their fortunes through placer mining. The area’s rich resources attracted both Native Americans and Spaniards who had inhabited the region long before American settlers arrived.

These communities steadily grew and merged by 1839, creating the larger settlement of Golden, which established itself around the newly built San Francisco Catholic Church. The historic church became an architectural centerpiece featuring a 200-year-old painting that remained there until its recent theft during restoration work.

First Gold Rush West

In 1825, the discovery of gold along Tuerto Creek near the Ortiz Mountains marked the first significant gold rush west of the Mississippi River.

You’ll find that this historic event predated California’s famous rush by over two decades. The initial gold discovery consisted of placer deposits – loose gold fragments in stream gravels that you could extract through simple mining techniques like panning and sluicing.

This area would eventually become a symbol of achievement for early prospectors in the American West.

Two mining camps quickly emerged: El Real de San Francisco and Placer del Tuerto.

These settlements grew as prospectors worked the narrow gulches and streambeds, focusing on shallow gravels where gold had naturally concentrated in crevices.

Two Communities Unite Together

Long before Golden earned its name, two distinct mining camps – El Real de San Francisco and Placer del Tuerto – flourished along Tuerto Creek during the 1820s.

Similar to Kingston’s story, which began as Purchase City, these settlements emerged around valuable mineral deposits.

These settlements shared a common mining heritage, extracting placer gold from the rich deposits around the Ortiz Mountains. The area marked the location of the first gold rush west of the Mississippi River.

By 1830, the San Francisco Catholic Church emerged as a unifying force, bringing both communities together for worship and celebrations like the Fiesta de San Francisco de Assis.

You’ll find that the church, with its locally crafted stained-glass windows, became the heart of their growing community identity.

As gold continued flowing from Tuerto Creek throughout the 1830s, these camps grew increasingly interconnected.

Merging of Two Communities

During the early years of New Mexico’s mining history, two bustling communities – Placer del Tuerto and Real de San Francisco – joined forces to establish the village of Golden. The 1825 discovery of precious metals sparked a transformative merger that would create the first gold rush west of the Mississippi. The town’s fate mirrored many others that became ghost town sites due to depleted resources.

New Mexico’s Gold Rush began when two villages united to form Golden after discovering precious metals in 1825.

Situated 10 miles south of Madrid, Golden became a key mining settlement in the central region of New Mexico.

You’ll find that this union wasn’t just about mining – it represented a remarkable blend of community dynamics and cultural exchange.

The merger proved strategically brilliant, as both settlements pooled their resources and workforce. Together, they built shared infrastructure, including stores and churches, while combining their unique traditions.

The unified town’s location along what’s now the Turquoise Trail Scenic Byway strengthened its position as a thriving hub until gold deposits waned in 1884, shaping the region’s mining legacy.

Native American and Spanish Heritage

Before Gold Rush settlers arrived, you’ll find evidence of Paa-Ko Pueblo‘s inhabitants who lived in this area between 1300-1670 CE, establishing a significant Native American presence.

Spanish colonial prospectors later discovered promising mineral deposits here, leading to mining activities that would shape the region’s future development.

The convergence of these two cultures – the indigenous Pueblo peoples and Spanish miners – left an indelible mark on Golden’s early history, visible in archaeological remains and historical records. The Pueblo peoples had developed sophisticated irrigation techniques and farming methods long before European contact in the region.

Early Paa-Ko Pueblo Settlement

Nestled in the fertile landscape between the Rio Grande and Estancia Valley, the Paa-Ko Pueblo emerged around 1300 A.D. as a thriving Ancestral Pueblo settlement.

You’ll find evidence of impressive Paa-Ko architecture in its 26 room blocks, arranged across eight plaza groups, where about 1,500 interconnected rooms once housed a bustling community. The pueblo’s inhabitants mastered Native agriculture, cultivating corn, beans, and squash in the well-watered floodplains.

What began as simple jacal-style dwellings in 1200 CE evolved into grand stone buildings by the 1300s.

The settlement’s strategic location fostered trade between the Plains and Rio Grande regions, while nearby springs and timber resources sustained the community until its primary abandonment in the 1400s, when residents moved closer to the Rio Grande floodplains.

Spanish Colonial Mining History

The Paa-Ko Pueblo’s decline in the 1400s left the region relatively quiet until Spanish settlers discovered the area’s rich mineral deposits in the early 1600s.

Spanish influence quickly transformed the mining landscape at El Real de los Cerrillos, where they shut down native turquoise operations and established lead and silver mines under formal colonial oversight.

You’ll find evidence of both Spanish and Indigenous mining techniques in the area, including primitive smelting methods and the advanced patio process.

The Spanish relied heavily on Indigenous labor, bringing in specialized Tlaxcalan miners from central Mexico and exploiting local Pueblo workers through forced labor systems.

This exploitation ultimately contributed to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, after which many mines were abandoned or concealed as natives refused to reveal their locations.

Golden’s Peak and Decline

During its heyday in the mid-19th century, Golden flourished as a bustling mining hub after establishing itself as the site of America’s first gold rush west of the Mississippi.

You’ll find that the economic impacts transformed two separate mining communities, Placer del Tuerto and Real de San Francisco, into a thriving town with stores, homes, and a post office by 1839.

The community evolution brought diverse settlers, from Native Americans to Spanish colonists and American miners.

Exploring the San Francisco Catholic Church

You’ll find the San Francisco Catholic Church has served Golden’s faithful since 1830, surviving both the town’s mining heyday and its eventual decline into a ghost town.

The church’s most significant transformation came in 1960 when historian Fray Angélico Chávez led a restoration that converted its “drab and inconspicuous” structure into a mission-style landmark.

Today, you can capture stunning photographs of the historic church perched dramatically on its precipice along Route 14, especially during the golden hours of sunrise and sunset when the adobe walls take on warm, distinctive hues.

Church History Since 1839

Founded in 1839 near the mining camps of El Real de San Francisco and Placer del Tuerto, San Francisco Catholic Church stands as a tribute to New Mexico’s early Spanish colonial heritage.

The church’s architecture reflects rural New Mexican mission design, built with adobe bricks and minimal ornamentation to serve the growing mining population.

You’ll find this historic church perched on a hill along the Turquoise Trail, where it’s weathered over a century of challenges.

After suffering severe storm damage in 1959-1960 and impacts from Route 14’s expansion, the church has undergone various restoration efforts.

Today, you’ll see preservation work continuing through Nuevo Mexico Profundo and St. Joseph Parish, who’ve partnered with Mudd Brothers Construction to protect this enduring symbol of community significance and religious perseverance.

Chavez’s 1960 Restoration Project

A pivotal moment in the church’s history arrived when Fray Angélico Chávez launched his ambitious restoration project in 1960.

After storms ravaged the church’s roof in 1959-1960, Chávez’s vision transformed the once-drab structure into a “sermon in stone” along the newly paved Route 14. As both a scholar and Franciscan priest who’d studied at the Vatican and Oxford, he understood the significance of architectural authenticity in preserving New Mexican heritage.

The restoration focused on repairing storm damage while enhancing the building’s mission-style features.

You’ll notice how Chávez strategically positioned the church to catch travelers’ eyes from its precipice location. His work maintained the original adobe structure while incorporating essential improvements like waterproofing and stucco stabilization, ensuring the church would remain a tribute to New Mexico’s Catholic missionary legacy.

Photography Tips and Views

Whether you’re a seasoned photographer or casual visitor, the San Francisco Catholic Church offers fascinating opportunities for dramatic shots along the Turquoise Trail.

Perched on a precipice alongside Route 14, this 1830s adobe mission stands as a symbol of New Mexico’s Spanish Colonial heritage.

For the most intriguing photographic techniques at this historic site:

- Position yourself during golden hour when the sun’s angle highlights the adobe’s warm tones and creates dramatic silhouettes.

- Use wide-angle lenses to capture the church’s relationship with the surrounding high desert landscape.

- Frame shots incorporating both the church and nearby mining ruins for historical context.

- Set up at scenic viewpoints along the highway, using the winding road as leading lines toward the mission.

Remember to bring a tripod for low-light conditions and polarizing filters to manage adobe surface glare.

Notable Historic Structures and Ruins

Standing as Golden’s most prominent landmark, the San Francisco Catholic Church anchors a compelling collection of historic structures and mining remnants that tell the story of this once-bustling New Mexico town.

Restored in 1960 by Fray Angelico Chavez, the church’s historical significance and architectural features make it the area’s most photographed building.

You’ll find fascinating ruins scattered throughout the landscape, including foundations of miners’ homes, abandoned mining facilities, and mysterious structures across the highway.

The ancient Paa-Ko pueblo ruins, dating to 1300 A.D., add another layer to Golden’s rich history.

While many buildings have succumbed to time and vandalism, these surviving structures provide a tangible connection to multiple eras – from Native American settlements to the town’s gold rush heyday and eventual decline after 1928.

Life Along the Turquoise Trail

Beyond the weathered structures and mining remnants, the Turquoise Trail holds a rich cultural tapestry spanning over a millennium. The Trail’s cultural significance extends from ancient Pueblo peoples to Spanish explorers and Anglo settlers, each adding their distinct mark on the region’s heritage.

Ancient footprints merge along the Turquoise Trail, where Pueblo, Spanish, and Anglo cultures weave an enduring legacy through time.

You’ll discover a fascinating history of turquoise craftsmanship, where the precious “sky stone” shaped local economies and traditions.

- Native Puebloans established extensive trade networks, with turquoise from Cerrillos Hills reaching as far as Mesoamerica.

- Spanish settlers integrated local mining techniques while introducing European jewelry designs.

- Mining towns like Golden fostered tight-knit communities of miners, ranchers, and artisans.

- Local economies adapted from pure mining to include ranching, farming, and tourism as times changed.

Modern-Day Preservation Efforts

As Golden’s historic structures face the relentless march of time, dedicated preservation initiatives have emerged to protect this essential piece of New Mexico’s mining heritage.

You’ll find heritage conservation efforts focusing on salvaging weathered adobe buildings while maintaining their authentic character, rather than completely reconstructing them.

Today’s preservation work combines archaeological assessments with sustainable tourism practices.

Local historical societies coordinate with volunteer groups to document the site through photographs and oral histories, while implementing solar energy solutions that respect the ghost town’s ambiance.

You’ll see carefully placed interpretive signs and stabilized trails that enhance visitor access without compromising historical integrity.

State grants and academic partnerships support ongoing research, ensuring that Golden’s mining legacy endures for future generations to explore and understand.

Visiting Golden Today

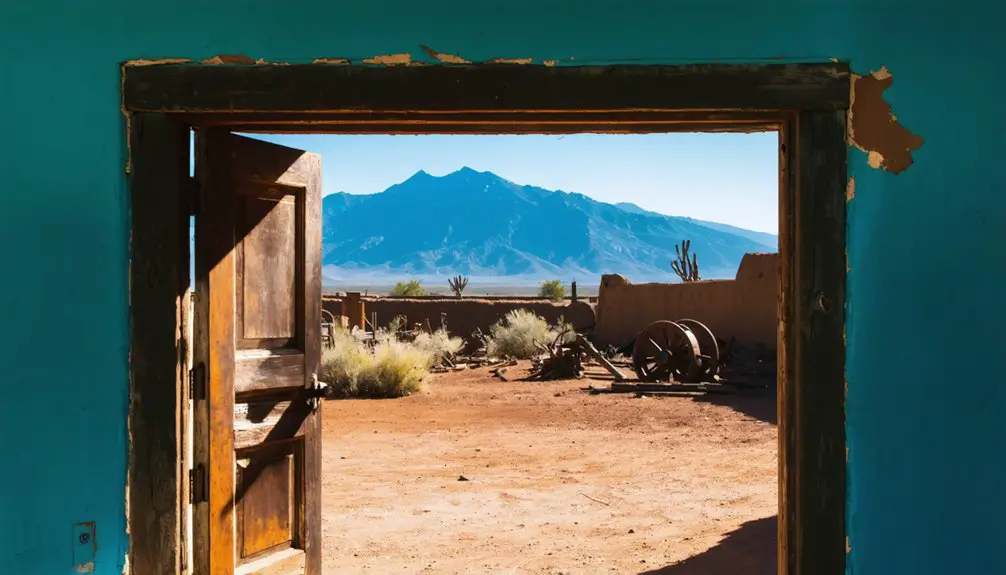

Today’s visitors to Golden will find this historic mining settlement nestled along New Mexico State Road 14, known as the Turquoise Trail Scenic Byway.

This semi-ghost town, with only 21 residents, offers authentic ghost town exploration opportunities amid the stunning Ortiz Mountains backdrop.

For the best experience during your visit:

- Start at the restored San Francisco de Asis Catholic Church, the town’s most photogenic landmark for scenic photography.

- Explore the Henderson Store ruins and mining remnants along the highway.

- Venture west of the church to discover additional historic structure ruins.

- Take advantage of hiking trails in the surrounding mountains.

You’ll need to be self-sufficient as there aren’t any visitor facilities in Golden.

The town’s accessible location, just 37 miles from Santa Fe, makes it perfect for an independent day trip adventure.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Dangerous Abandoned Mine Shafts Visitors Should Avoid?

You’ll find hazardous mine shafts scattered throughout the area’s mining ruins. While these sites spawn fascinating ghost stories, they’re unstable and deadly. Stay on marked paths for your safety.

What Are the Current Property Prices and Availability in Golden?

Like finding a vintage iPhone in a ghost town, your real estate options are extremely limited. There’s just one property listed at $3.2 million, reflecting unique property trends in this historic area.

Is Camping or Overnight Parking Allowed in the Golden Area?

You’ll need to camp outside Golden, as there’s no designated camping within town. BLM lands nearby allow dispersed camping for up to 14 days, while El Morro offers established campgrounds with basic amenities.

Does Golden Have Any Annual Festivals or Community Events?

You won’t find any regular community traditions or local celebrations in Golden today. As a ghost town, it doesn’t host annual festivals, though you can explore nearby regional events in active New Mexico communities.

Are Metal Detecting and Artifact Collecting Permitted in Golden?

You can’t legally metal detect or collect artifacts in Golden without proper permissions. On private land, you’ll need landowner consent, while public areas are protected by strict federal regulations.

References

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/nm-golden/

- https://www.newmexicoghosttowns.net/golden-nm

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/

- http://coloradosghosttowns.com/Golden NM.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_New_Mexico

- https://npshistory.com/publications/jeff/newsletters/museum-gazette/gold-rush-1.pdf

- https://www.voanews.com/a/a-13-2007-07-05-voa33-66565792/555173.html

- https://knowingnewark.npl.org/all-that-glittered-wasnt-california-gold-for-49ers-from-newark/

- https://historylizzie.co.uk/2020/08/18/the-first-american-gold-rush/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_rush