You’ll find Golden, a former mining boomtown, nestled in Box Elder County, Utah, where gold was first discovered in 1892. During its heyday, the town supported up to 500 residents with saloons, gambling halls, and brothels typical of Wild West settlements. Today, about five structures remain from the original thirty-plus buildings, including an adobe schoolhouse and mining equipment remnants. The ghost town’s remote location and rugged terrain hold countless stories of Utah’s mining past.

Key Takeaways

- Golden was a notorious Utah boomtown that emerged during the mining boom, characterized by saloons, gambling halls, and lawlessness.

- Located 6 miles west of Park Valley at the Raft River Mountains’ base, the ghost town is accessible but requires a high-clearance vehicle.

- Only five structures remain from the original thirty-plus buildings, including a historically significant adobe schoolhouse and mining equipment remnants.

- The town produced over $100 million in minerals during its peak before declining due to falling ore prices and economic pressures.

- The Panic of 1907 marked Golden’s transformation into a ghost town, with the population dropping from 500 despite brief resurgences.

The Origins of Golden’s Mining Legacy

While Utah’s early settlers focused primarily on agriculture, the arrival of Colonel Patrick E. Connor and his California and Nevada Volunteers in 1862 marked a turning point in the territory’s mining history.

These experienced prospectors began exploring the region’s mountains, leading to Utah’s first gold discovery at Gold Hill in Tooele County in 1858. The establishment of formal mining claims in Bingham Canyon followed in 1863.

Gold seekers ventured into Utah’s peaks, striking gold at Tooele’s Gold Hill before establishing mining claims in Bingham Canyon.

The arrival of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 revolutionized mining techniques by enabling efficient ore transport. British investments peaked between 1871-1873, particularly in ventures like the Emma Mine.

As mining districts organized throughout the territory, prospectors discovered valuable placer gold deposits in Bingham Canyon, which would yield $1.5 million before 1900. The West Mountain district became the first organized mining area in Utah’s history.

The Mercur District’s formation in 1870 introduced advanced mining techniques, particularly the cyanide process, transforming previously uneconomical microscopic gold deposits into profitable ventures.

Life in a Wild West Boomtown

As mining towns exploded across Utah’s rugged landscape, Golden emerged as one of the territory’s most notorious boomtowns, where lawlessness and violence claimed up to 50 lives per day.

The rough-and-tumble saloon culture dominated daily life, with makeshift tents eventually giving way to permanent structures that housed gambling halls, brothels, and watering holes. Similar to Frisco’s peak years, the town boasted over 23 saloons catering to thirsty miners and drifters. The dangerous mining conditions led to a shockingly high childhood mortality rate, evident in the local cemetery’s numerous small graves.

- You’d find hastily built adobe and wooden structures clustering around the main street.

- Law enforcement often took brutal measures, with criminals being shot on sight.

- You could spot wanted posters warning troublemakers to leave town or face hanging.

- Your entertainment options centered around dance halls and card rooms.

Life in Golden revolved around these social hubs, where miners and entrepreneurs gathered in a mainly male society.

The town’s population ebbed and flowed with each new strike, creating a constantly shifting community of fortune seekers.

Mining Operations and Economic Growth

Though Golden’s mining legacy began with individual prospectors, the arrival of Colonel Patrick E. Connor in 1862 transformed Utah’s mining landscape.

You’ll find that early discoveries in Bingham Canyon and Little Cottonwood Canyon quickly attracted foreign investments, particularly British capital between 1871-1873.

The introduction of new mining technologies revolutionized operations, especially at the Golden Gate mill in Mercur, which became America’s largest cyanide facility in 1897. Led by metallurgical superintendent Daniel C. Jackling, the mill pioneered innovative extraction methods. The success of copper mining in nearby Bingham Canyon helped drive further technological advancements in the region.

The economic impacts were substantial, with gold deposits yielding impressive returns from high-grade veins containing 6-20+ g/t gold.

The Getty Oil Company’s 1980s revival and Barrick Gold’s operations until 1995 demonstrated the area’s lasting mineral wealth.

These operations employed modern extraction methods like open pit mining and heap leaching, producing over 100,000 ounces of gold annually before reserves were finally depleted.

Notable Structures and Remaining Landmarks

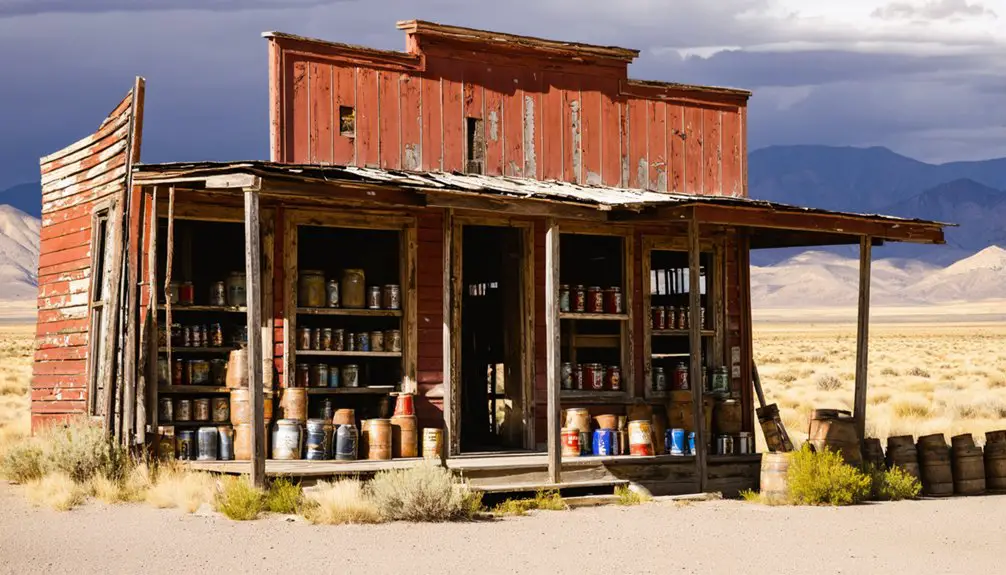

You’ll find several remaining buildings among Golden’s deteriorating landscape, with only about five structures standing from the original thirty-plus that once formed this mining settlement.

During its peak, the town produced over $100 million in minerals, reflecting the tremendous wealth generated by Utah’s mining industry.

Similar to other mining communities like Silver Reef in 1879, devastating fires swept through parts of Golden, contributing to its eventual decline.

Stone foundations and crumbling walls mark where other buildings once stood, while rusting mining equipment and scattered tool collections provide evidence of the town’s industrial past.

The adobe schoolhouse stands as one of the most historically significant surviving structures, featuring preserved original elements like its roofing and windows.

Mining Equipment Remnants

While exploring the Bully Boy Mill area of Golden, you’ll discover significant mining equipment remnants that paint a vivid picture of the town’s industrial past.

The mining equipment evolution is evident through preserved components that showcase the era’s industrial ingenuity. Pneumatic drills and blasting equipment used for dynamite placement were essential tools of the trade. The old train station once facilitated the transportation of valuable ore and mining equipment to and from the area.

- A well-preserved miners’ cabin features an intact drill press and tool sharpening station, demonstrating early machinery preservation techniques.

- The vertical mine shafts still contain ore buckets used for mineral extraction, alongside a nearly complete steam boiler system.

- A sophisticated 24-inch wooden pipe system remains, which once powered the stamp mill operations.

- Large geared wheels and sifting devices illustrate the ore processing sequence, designed for crushing and screening minerals.

These remnants reveal the interconnected nature of mining operations, from extraction to processing, that once drove Golden’s prosperity.

Abandoned Building Foundations

Scattered across Golden’s landscape, numerous building foundations reveal the town’s once-thriving commercial and civic infrastructure. You’ll find these abandoned foundations constructed primarily from local stone, with some featuring distinctive purplish-pink hues characteristic of Utah ghost town architecture.

The most substantial remains include former store foundations and partial walls, typically clustered near what was once the town’s main thoroughfare.

Along the settlement’s perimeter, you’ll discover residential foundation ruins, many still displaying remnants of fireplaces and heating stove footprints that hint at domestic life in this harsh mining environment.

These stone footers and scattered wall segments paint a picture of Golden’s layout, while civic building foundations, including a weathered schoolhouse foundation, stand as evidence of the community’s former social organization and development.

The Decline and Abandonment Era

Mining operations in Golden faced significant challenges during the early 20th century, as declining ore prices and increased operational costs forced many mines to scale back or shut down completely.

You’ll find that these economic pressures, combined with management changes typical of Utah’s mining towns, led to widespread worker dissatisfaction and a steady exodus of miners and their families.

The town’s population dwindled rapidly as residents sought opportunities elsewhere, following patterns similar to other mining communities like Kimberly, where populations dropped from hundreds to single digits within a decade.

Mining Operations Cease

As economic challenges mounted in the late 20th century, Golden’s once-thriving mining operations faced a series of insurmountable obstacles.

The economic impacts of declining surface deposits forced deeper, more capital-intensive mining methods, while technological advancements couldn’t offset the rising costs.

You’ll find several key factors that led to the eventual shutdown:

- The exhaustion of economically viable ore reserves made continued operations unsustainable

- Complex ore bodies required expensive extraction and processing techniques

- World War II regulations forced some operations to close permanently

- Fluctuating gold prices and corporate consolidations disrupted mining traditions

The combination of these challenges, along with stricter environmental regulations and the need for costly reclamation efforts, ultimately sealed Golden’s fate.

Large corporations withdrew their interests, and the once-bustling mining town fell silent.

Population Exodus Patterns

The Panic of 1907 sparked a dramatic exodus from Golden, Utah, marking the beginning of the town’s transformation into a ghost town. The financial crisis devastated the mining industry, forcing businesses to relocate and leaving miners with worthless scrip instead of legal tender.

Population trends show the town’s decline from its peak of 500 residents as families sought opportunities elsewhere.

You’ll find that migration patterns followed the boom-bust cycle of mining operations. While brief resurgences in 1910 and 1920 brought the population back to around 300 workers, these temporary revivals couldn’t sustain long-term settlement.

Most residents moved to neighboring towns like Park Valley and Rosette, taking their possessions and economic activity with them. The exodus continued until Golden’s infrastructure crumbled, leaving only abandoned buildings as evidence of its former liveliness.

Exploring the Ghost Town Today

Located 6 miles west of Park Valley at the southern base of Utah’s Raft River Mountains, Golden stands today as a remote ghost town waiting to be explored.

For ghost town photography enthusiasts and adventurers, the site offers a raw, unfiltered glimpse into Utah’s mining past, though visitor safety requires careful preparation.

When exploring Golden’s remains, you’ll find:

- Abandoned mine shafts and weathered foundations scattered across the rugged terrain

- Old tramway routes and mill foundations near the historic Vipont Mine area

- Natural desert vegetation reclaiming the former townsite

- Opportunities for self-guided exploration among the ruins

You’ll need to bring your own supplies and a high-clearance vehicle to access the site.

With no cell service or amenities available, proper preparation is essential for a safe visit to this remote location.

Historical Significance in Utah’s Mining Heritage

Beyond the physical remnants you’ll find today, Golden holds deep historical importance in Utah’s mining narrative. The town’s 1899 discovery of gold-rich ore helped establish Utah’s reputation as a major precious metals producer, eventually ranking sixth in U.S. gold production through 1960.

You’ll see Golden’s cultural impact reflected in its diverse community, including Chinese workers whose presence archaeologists have documented through recovered artifacts and currency.

The town exemplifies the quintessential mining heritage of Utah through its dramatic boom-and-bust cycles, technological innovations like the 1920s tramway, and adaptation to changing mineral discoveries.

Golden’s story captures the broader socio-economic dynamics of mining communities, from labor relations to immigration patterns, making it a valuable window into Utah’s complex mining history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Documented Paranormal Activities or Ghost Sightings in Golden?

80% of paranormal investigators report activity here. You’ll find documented ghost stories of shadow figures, aggressive entities, and unexplained voices throughout haunted locations, especially during dusk-to-dawn investigations on Golden’s grounds.

What Wildlife Species Can Visitors Commonly Encounter Around the Ghost Town?

You’ll likely spot mule deer and coyotes during twilight hours, while hawks soar overhead during day. Wildlife observation opportunities include desert cottontails, various songbirds, and lizards for species identification.

Was Golden Ever Featured in Any Western Movies or Television Shows?

Preciously preserved records don’t show Golden featuring in any Western films or TV shows. You’ll find nearby Utah towns like Kanab and Johnson Canyon served as popular Western locations instead.

Did Any Famous Outlaws or Historical Figures Visit Golden During Its Heyday?

You won’t find any confirmed outlaw legends or historical visits by famous figures in Golden’s history. The town’s isolation and mining-focused economy didn’t attract well-known outlaws during its peak years.

How Many Deaths Occurred in Golden’s Mines During Its Operational Years?

Like secrets buried in time’s depths, you won’t find exact death counts from Golden’s mines. Historical records on mine safety are incomplete, though crushing accidents and cave-ins likely claimed lives there.

References

- https://www.valleyjournals.com/2024/10/02/507818/exploring-utah-s-ghost-towns-seven-abandoned-settlements-with-fascinating-histories

- https://www.roadtripryan.com/go/t/utah/westdesert/gold-hill-and-clifton-ghost-towns

- https://digging-history.com/2014/05/21/ghost-town-wednesday-kimberly-utah/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enJ7WoZuGLc

- https://www.utahoutdooractivities.com/goldhill.html

- https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/m/MINING.shtml

- https://geology.utah.gov/popular/rocks-minerals/utah-gold/

- https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1357/report.pdf

- https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/survey-notes/the-mercur-district-a-history-of-utahs-top-gold-camp/

- https://www.deseret.com/1989/11/26/18834123/legends-of-utah-gold/