Greasertown emerged in 1851 during the California Gold Rush as a Hispanic mining settlement along the Calaveras River. You’ll find its history marked by ethnic tensions, as Hispanic miners were forcibly expelled following a fire in 1852. The community declined by the late 1850s as gold deposits dwindled, and ultimately vanished beneath the waters of Hogan Dam in the 1920s. This submerged ghost town reveals the complex racial dynamics that shaped California’s mining frontier.

Key Takeaways

- Greasertown was a Gold Rush settlement established in 1851 on the western banks of the Calaveras River in Calaveras County.

- Originally founded by Mexican miners, the town experienced significant ethnic tensions after an 1852 fire led to Hispanic residents’ expulsion.

- The mining community featured placer mining operations, makeshift housing, and W.C. Mills’ general store until at least 1858.

- Greasertown began declining in the late 1850s as miners abandoned the site for richer diggings elsewhere.

- The ghost town was completely submerged beneath Calaveras River reservoir after Hogan Dam construction in the late 1920s.

The Origins of a Gold Rush Settlement

As gold fever swept through California in the mid-19th century, Greasertown emerged as one of many hastily established settlements catering to fortune seekers.

First appearing in historical records in 1851, this community took root on the western banks of the Calaveras River, just four miles from San Andreas.

You’ll find that Greasertown’s development directly mirrored the rapid influx of miners utilizing various mining techniques along the river.

The settlement’s economy and social structure formed around these transient populations, with businesses focused on supporting prospecting activities. W.C. Mills operated a general store in the settlement until at least 1858, providing essential supplies to the mining community.

Greasertown eventually became one of California’s numerous ghost towns, abandoned as the gold rush waned and populations moved to more prosperous areas.

Unlike nearby Petersburg (established 1858), Greasertown originated earlier amid ethnic tensions that culminated in an 1852 fire blamed on “Spanish incendiaries” – an incident that prompted Hispanic expulsion from the community, revealing the volatile social dynamics that characterized early California gold settlements.

From Boom to Bust: Greasertown’s Brief History

You’ll find Greasertown’s arc followed the classic boom-to-bust pattern of Gold Rush settlements, beginning with the frenzied influx of prospectors who established a vibrant but ethnically divided community.

Tensions between Mexican miners and Anglo settlers erupted frequently, creating a social powder keg that destabilized the town even as mining operations began to falter.

The town experienced rapid population decline in the 1880s as its natural resources depleted, mirroring the fate of other California ghost towns.

In a pattern reminiscent of many ghost town narratives, the settlement’s decline was accelerated when violence against Native Californians in the area contributed to regional instability.

Greasertown’s final chapter came when the construction of a regional reservoir submerged the abandoned settlement beneath rising waters, erasing most physical evidence of its brief but tumultuous existence.

Origins in Gold Rush

Nestled along the west side of the Calaveras River in Calaveras County, Greasertown emerged in 1851 during the height of the California Gold Rush, establishing itself as one of many hopeful settlements that dotted the Sierra Nevada foothills.

This Mexican community, initially called Greaser Ville, attracted settlers seeking fortune in the area’s rich gold deposits.

The settlement’s strategic positioning enabled three key developments:

- Implementation of placer mining techniques along the Calaveras River

- Establishment of trade centers supporting mining operations

- Formation of a primarily Mexican-American community showing remarkable community resilience

Despite its modest size, Greasertown quickly gained recognition as a significant mining hub in Calaveras County.

Its economy thrived on small-scale gold extraction, with miners developing specialized mining techniques adapted to local conditions before demographic shifts dramatically altered the town’s character. Today, the ghost town’s history is preserved through local podcasts that share stories of this once-bustling mining community.

Ethnic Tensions Erupt

The peaceful coexistence in Greasertown would prove short-lived. Just one year after the settlement’s first newspaper mention in 1851, a devastating fire swept through the community, igniting more than buildings. Local Anglo settlers immediately blamed “Spanish incendiaries,” exemplifying the scapegoating dynamics that characterized California’s gold rush settlements.

This ethnic conflict erupted from underlying economic competition and cultural mistrust. You’d have witnessed angry mobs forcibly expelling Hispanic residents, permanently altering the town’s demographic composition.

Despite their significant contributions to the mining community, Hispanics became convenient targets during crisis. The expulsions diminished Greasertown’s cultural diversity and weakened its social fabric, though the settlement persisted into the 1860s.

This violent episode reflects the fragile nature of frontier communities where economic pressures could rapidly transform neighbors into adversaries.

Vanished Beneath Waters

While Greasertown managed to survive ethnic tensions and continued as a functioning settlement into the 1860s, its gold deposits proved disappointingly finite.

By the late 1850s, miners abandoned the site for richer diggings, leaving a shell of its former bustling self. The town’s fate was permanently sealed in the late 1920s with the construction of Hogan Dam, which submerged the settlement beneath the Calaveras River reservoir. Much like hydraulic mining bans affected towns such as North Bloomfield, Greasertown’s history represents how economic and environmental factors shaped California’s ghost towns. Similar to Bodie, the town experienced a rapid decline after its resources were depleted, though without preservation as a historical landmark.

Today, Greasertown remains:

- Completely underwater at coordinates 38°10′54″N 120°46′10″W

- Absent from any historical preservation efforts

- Inaccessible to underwater archaeology due to reservoir conditions

You’ll find no visible remnants of this once-thriving community.

Greasertown exemplifies how infrastructure projects have erased physical evidence of California’s gold rush heritage, trading the preservation of history for water management priorities.

Cultural Tensions and Racial Dynamics

Greasertown’s history reveals stark ethnic tensions, most prominently in 1852 when Hispanic residents were collectively blamed and expelled following a destructive fire that swept through the settlement.

This incident exemplifies the racial hierarchy of Gold Rush California, where Mexican and Native American miners faced discrimination despite their significant contributions to mining techniques and local economies. Similar prejudice occurred in Campo Seco mining camp, where forty different nationalities competed for resources amid escalating cultural conflicts.

You’ll find that these cultural conflicts fundamentally shaped Greasertown’s development and ultimate decline, reflecting broader patterns of ethnic scapegoating that occurred throughout California’s mining communities during the mid-19th century.

Ethnic Displacement Events

Following a brief period of settlement in 1851, Greasertown experienced a devastating fire in 1852 that would permanently alter its ethnic composition and social dynamics.

Local residents hastily blamed “Spanish incendiaries,” triggering systematic ethnic cleansing of Hispanic residents without substantive evidence.

This racial scapegoating followed a predictable pattern seen throughout Gold Rush communities, where resource competition fueled xenophobia.

The aftermath included:

- Forcible expulsion of Hispanic families from their homes

- Demographic transformation favoring Anglo settlers

- Erasure of Hispanic cultural influence in the town’s continued development

Though Greasertown persisted into the 1860s, its character had fundamentally changed.

The displaced Hispanic population never returned in significant numbers, cementing the demographic shift begun through violence and exclusion—a reflection of how racial animosity shaped California’s early mining settlements.

Gold Rush Racial Hierarchy

The ethnic displacement in Greasertown reflected a much broader and more complex racial hierarchy that dominated California’s Gold Rush society. White miners established and violently enforced a rigid mining hierarchy that systematically excluded Black, Indigenous, Chinese, and Mexican laborers from claim ownership and equal participation.

You’ll find that this racial exclusion operated through both informal camp laws and institutional frameworks. White labor organizations like the Knights of Labor deliberately refused membership to non-white miners, ensuring wage disparities persisted.

Legal barriers further entrenched this system—California’s 1850 statutes prohibited non-white testimony against whites in court, effectively sanctioning violence against marginalized groups. Despite this discrimination, African Americans formed mutual-aid societies to provide support and community in these hostile environments. Indigenous women were particularly vulnerable, facing extreme levels of sexual violence and exploitation during this period.

The devastating consequences were clear: Native American populations plummeted by 80%, while Chinese miners faced targeted taxation and violence.

Despite California’s “free state” status, approximately 300 enslaved Black individuals still labored in the gold fields by 1852.

Hispanic Mining Contributions

While Hispanics made essential contributions to Greasertown’s mining economy, their presence became increasingly threatened by escalating cultural tensions and racial hostilities.

Hispanic heritage infused the early settlement with traditional mining techniques from Mexican mining culture, providing valuable expertise during the Gold Rush era.

The 1852 fire catalyzed violent exclusion when Anglos blamed “Spanish incendiaries,” destroying the community’s fragile coexistence.

You can trace the rapid deterioration through:

- Initial scapegoating of Hispanics for the fire

- Organized expulsion campaigns targeting Hispanic residents

- Systematic exclusion from white-dominated mining operations

Despite this persecution, Hispanic miners persisted in the region through the 1860s, though their population never recovered from the violent displacement.

This cultural fracturing ultimately contributed to Greasertown’s abandonment before its submergence under Hogan Dam in the 1920s.

Life in a Mining Community

As Mexican miners established Greasertown along the Mokelumne and Calaveras rivers in the mid-19th century, they created a community that exemplified the typical mining settlement’s diverse and transient nature.

The community dynamics were characterized by ethnic tensions, particularly after enforcement of the “foreign miners tax” drove many Mexican residents away.

Mexican miners faced systematic displacement through discriminatory taxation, reshaping the cultural landscape of Gold Rush settlements.

Daily life centered around labor-intensive mining work yielding $5-10 daily when successful.

You’d find yourself living in makeshift housing, from tents to simple cabins, while working long hours in physically demanding conditions. The mining lifestyle required participation in water management systems essential for successful operations.

As the settlement developed, you’d patronize the emerging social institutions—saloons, trading posts, and hotels—while steering through an informal justice system based on self-made rules rather than official California law enforcement.

The Calaveras River Valley Before the Dam

Before dam construction forever altered its landscape, Calaveras River Valley existed as a dynamic watershed characterized by complex hydrology and diverse ecosystems. The fertile floodplains supported thriving agricultural practices, producing hay, strawberries, and tomatoes while seasonal river flows maintained critical river ecosystems.

Early water management evolved from mining to agricultural purposes, with three major developments:

- Establishment of the Calaveras County Water Company in 1856

- Construction of the Mokelumne Hill Canal in 1852, extending 60 miles by 1859

- Gradual infrastructure improvements throughout the late 19th century

Limestone deposits near the valley enabled industrial growth, particularly with the Calaveras Cement Company’s founding in the 1920s.

This industrial expansion, alongside agricultural development, positioned the valley as a regional economic hub before reservoir construction submerged farmland to satisfy growing urban water demands.

Beneath the Waters: Submersion and Disappearance

Once the construction of Hogan Dam began in the late 1920s, Greasertown’s fate was sealed beneath the rising waters of the new Calaveras River reservoir.

Unlike ghost towns abandoned due to economic decline, Greasertown was deliberately sacrificed for infrastructure impacts deemed necessary for regional development. The settlement that had stood since at least 1851 vanished as the dam filled, transforming the river valley’s geography forever.

You’ll find no archaeological excavations of this former Gold Rush community—its buildings, artifacts, and physical legacy lie preserved but inaccessible underwater.

This submersion represents the tension between progress and historical preservation that characterized early 20th-century America. While other towns relocated, Greasertown simply disappeared, leaving only written records and oral histories to document its existence approximately 4 miles west of San Andreas.

Remembering Lost Towns of the California Gold Rush

While Greasertown vanished beneath Calaveras Reservoir’s waters, it represents just one among hundreds of California Gold Rush settlements that disappeared under different circumstances.

The mining heritage of these forgotten communities follows a predictable pattern you’ve seen throughout California’s history—rapid growth followed by devastating decline when gold deposits were exhausted.

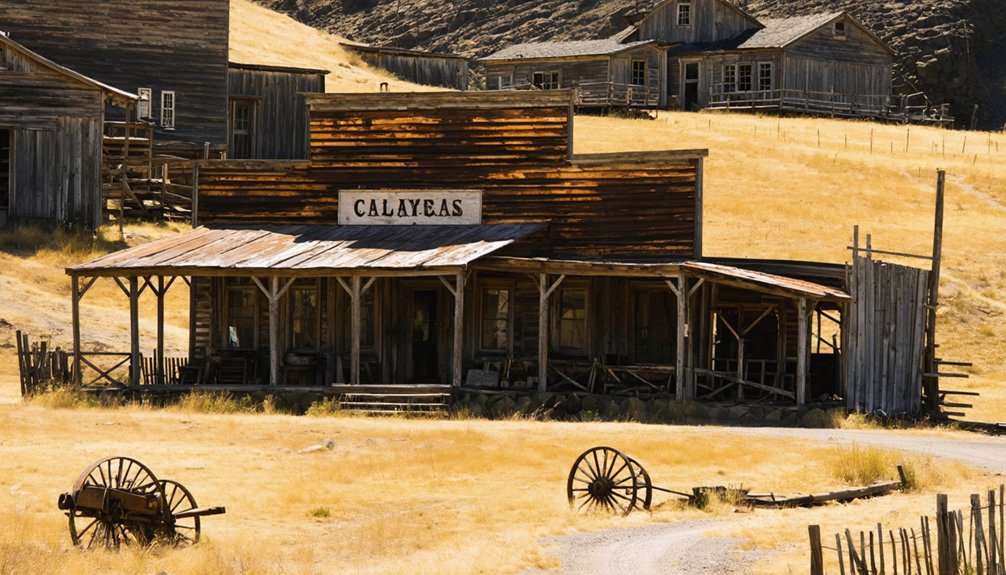

Today, ghost town restoration efforts preserve this legacy through:

Preserving California’s Gold Rush heritage gives us tangible connections to the fleeting dreams of frontier prosperity.

- State parks like Bodie, maintained in “arrested decay”

- Open-air museums such as Silver City, featuring relocated historic structures

- Converted tourist attractions like Calico, now a California State Historic Landmark

These preservation projects serve as physical reminders of the boom-bust cycle that defined the Gold Rush era, offering you glimpses into the transient nature of prosperity built solely on resource extraction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Artifacts Recovered Before Greasertown Was Submerged?

No documented artifacts were recovered before submersion. You’ll find this gap in underwater archaeology significant, as valuable historical material remains inaccessible beneath Hogan Dam’s waters since the 1920s.

Can Divers Explore the Underwater Remains of Greasertown Today?

Beneath murky depths, this forgotten ghost town awaits. You likely can’t legally explore Greasertown’s underwater remains today due to reservoir regulations, archaeological preservation laws, and permit requirements governing underwater exploration of historic sites.

Did Any Greasertown Buildings Get Relocated Before Flooding?

No evidence suggests any buildings were relocated. You’ll find no record of building preservation efforts despite Greasertown’s historical significance—a stark contrast to some ghost towns that maintained their structural legacy.

Are There Any Living Descendants of Original Greasertown Residents?

While you’d expect extensive Greasertown genealogy records, there’s no documented evidence of living descendants. Historical research hasn’t identified family reunions or lineages connecting modern individuals to the ghost town’s original inhabitants.

Does Hogan Lake’s Water Level Ever Drop Enough to Reveal Ruins?

No definitive evidence suggests Hogan Lake’s water level fluctuations expose submerged ruins. Even during significant drawdowns like 2015’s historic low, records don’t document any revealed structures beneath the reservoir.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greasertown

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD9M6MP6RRU

- https://www.camp-california.com/california-ghost-towns/

- https://www.californist.com/articles/interesting-california-ghost-towns

- http://cali49.com/hwy49/tag/Ghost+Town

- https://dornsife.usc.edu/magazine/echoes-in-the-dust/

- https://www.historicalcalaveras.com/_files/ugd/f6d3c3_e9fe2b85908f48ce83cf6b3127c2f63f.pdf?index=true

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://parks.sbcounty.gov/opinion-beyers-byways-a-brief-history-of-calico-ghost-town/

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Greasertown