Greenwater was a copper boomtown in Death Valley that flourished briefly from 1906-1909. You’ll find a dramatic story of speculation where water cost $15 per barrel and temperatures swung from 120°F to below freezing. Charles Schwab’s investment triggered a $30 million speculation frenzy before the town collapsed completely by 1908. Only scattered debris remains today where 2,000 people once chased copper dreams in the harsh desert landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Greenwater was a copper mining boomtown established around 1904-1905 in Death Valley that grew to over 2,000 residents across four settlements.

- Water scarcity was extreme, with costs reaching $15 per barrel, making it more valuable than whiskey in the harsh desert climate.

- The town experienced a meteoric rise with $140 million in investments after Charles Schwab’s involvement triggered a copper speculation frenzy.

- Mining operations failed to meet expectations by 1907, causing rapid abandonment and complete desertion by 1909.

- The post office closed in August 1908, marking the official end of Greenwater, which had vanished just a few years after its founding.

The Copper Rush That Created a Desert Boomtown

Though the original discoverer remains disputed, copper was first found in Greenwater Valley around 1904-1905, igniting what would become one of California’s most explosive mining booms. Several prospectors—Arthur Kunze, Shorty Harris, Phil Creasor, and Fred Birney—all claimed credit for the copper discovery that transformed this remote desert region.

Surface indications proved so promising that investors dubbed it “the world’s greatest copper deposit,” attracting major mining magnates despite severe water shortages and transportation challenges. By May 1906, surveyors confirmed the copper belt extended at least seven miles.

Mining techniques evolved rapidly as shafts were sunk and round-the-clock operations began. Within eighteen months, the area boasted four bustling towns with over 2,000 residents and 73 incorporated mining companies representing an astonishing $140 million in capital investment. The district experienced the shortest lifespan of any mining boom of its size in recorded history. Unfortunately, most operations yielded little valuable ore, and by early 1909, the boom collapsed with less than $100,000 in profit.

Life in a Waterless Frontier: Daily Struggles

In Greenwater’s parched desert landscape, you’d pay up to $15 per barrel (about $450 today) for water transported by mule teams across miles of scorching terrain.

Your canvas tent offered minimal protection against extreme temperature swings, with daytime heat exceeding 120°F and nighttime temperatures plummeting below freezing. Similar to modern California’s water scarcity struggles, residents faced constant uncertainty about when the next shipment would arrive. The crisis echoed California’s historical pattern of water claims dramatically exceeding available resources, a problem that persists today.

Mining copper ore exposed you to deadly risks including cave-ins, toxic dust inhalation, and explosive accidents—hazards compounded by the absence of medical facilities in this remote outpost.

Liquid Gold Economics

Water became the ultimate commodity in Greenwater, often commanding higher prices than whiskey in this parched Death Valley outpost.

You’d find your mining profits quickly drained by the relentless demands of the water trade, as wagon deliveries from distant sources imposed severe economic burdens on daily operations.

The harsh economics transformed water into a business liability. Mining logistics became nightmarishly complex when every drop needed for ore processing had to be hauled in at premium rates. Like modern California’s State Water Project, Greenwater’s water distribution system was fundamentally linked to economic survival. This struggle mirrored the conflicts seen when armed ranchers dynamited parts of the Los Angeles Aqueduct to restore water flow to their lands.

Your ability to invest in equipment, pay workers, or expand operations diminished with each water shipment.

Without reliable water infrastructure, Greenwater couldn’t diversify beyond mining.

Any disruption in delivery routes meant immediate economic hardship for you and fellow residents.

This fundamental resource instability ultimately rendered the town’s economy unsustainable, contributing to its abandonment and ghost town fate.

Canvas Living Challenges

Life in Greenwater typically meant pitching your canvas tent amidst swirling dust and relentless heat, where the struggle for daily survival extended far beyond mining operations. Your canvas living quarters offered minimal protection from frequent dust storms that intensified dehydration risks in this waterless frontier.

Basic survival strategies revolved around water conservation. You’d prize canned tomatoes over costly water for quenching thirst, with prices reaching $20 per barrel when supply wagons broke down. Your daily routine included hauling water not just for drinking, but cooking and minimal washing. The town’s peak population of around 1,000 people intensified competition for limited water resources.

Without infrastructure, sanitation challenges threatened community health. The absence of reliable water prevented livestock keeping or gardening, forcing complete dependence on imported supplies.

When water wagons failed to arrive, the entire community faced immediate crisis—a harsh reality that ultimately contributed to Greenwater’s abandonment.

Deadly Mining Hazards

Mining in Greenwater exposed you to deadly hazards extending far beyond the mere absence of water. The toxic legacy persists in mercury and cyanide-laden soils, with heavy metals like arsenic and lead contaminating limited water supplies and creating airborne dust particles you’d inevitably breathe.

Physical mining dangers lurked everywhere – unstable tunnels prone to collapse, flooded shafts mixing toxic chemicals with groundwater, and precarious ruins of mining structures that could give way without warning.

Tailings piles remained unstable, threatening landslides during rare but intense desert storms. Similar to the estimated 47,000 abandoned mines scattered throughout California, Greenwater’s neglected sites posed ongoing environmental threats long after operations ceased.

At $15 per barrel for imported water, dust suppression was impossible, forcing you to inhale contaminated particles daily. These conditions mirrored the widespread ecological damage that mining activities inflicted throughout California.

Even abandoned sites harbored hidden threats – old explosives, chemical drums, and contaminated debris dams that could suddenly release their poisonous contents.

The Merger of Kunze and Ramsey: Birth of Greenwater

Two competing camps, established separately by Arthur Kunze and Harry Ramsey, formed the foundation of what would become Greenwater.

Each entrepreneur had developed their own infrastructure—Kunze with his lodging house, store and assay office, while Ramsey incorporated the Greenwater Townsite Company with his restaurant, saloons and hotel.

The competition ended when railroad surveyors favored Ramsey’s lower elevation site.

Jack Salisbury and mining investors orchestrated a townsite consolidation backed by substantial mining capital approaching $25 million.

You’d have witnessed a carnival-like atmosphere as businesses physically relocated downhill, operating in both locations during the shift. Charles Schwab’s Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company had invested heavily in the region’s copper mining prospects.

The merged town adopted the name Greenwater, with equivalent lots provided to previous owners.

Despite ambitious plans for infrastructure and a $60,000 hotel, water supply remained a critical challenge, costing $15 per barrel.

Economic Rise and Spectacular Collapse (1906-1909)

You’ll find Greenwater’s economic trajectory defined by Charles Schwab’s 1906 investment, which triggered a copper speculation frenzy that drew 2,000 residents, a dozen saloons, and established transportation links to this remote Death Valley outpost.

By 1907, mining operations failed to produce expected yields, prompting rapid business closures, population exodus, and newspaper coverage that shifted from promotional to reassuring as investors lost confidence.

The town’s spectacular collapse culminated with the post office closure in August 1908, leaving no physical structures visible today within what’s now Death Valley National Park boundaries.

Copper Fueled Speculation

The copper discoveries at Greenwater sparked one of the most frenzied mining booms of the early 20th century, turning a barren Death Valley location into a hotbed of speculation between 1906 and 1909.

You’d have witnessed copper speculation reaching extraordinary heights as industry titans like Charles Schwab, F. August Heinze, and the Amalgamated Copper Company poured millions into claims.

Mining investors rushed to secure stakes in what newspapers heralded as America’s next great copper district, with estimates of $30 million invested during peak months.

Despite scarce water costing $15 per barrel and challenging transportation, the promise of seven miles of copper-rich terrain drove stock prices skyward.

Rapid Fall, Total Abandonment

While many Western boomtowns experienced slow decline, Greenwater’s collapse came with stunning speed and totality. By spring 1907, the copper dream was already unraveling, triggering an unprecedented population exodus.

What had been a thriving town of 2,000 dwindled to just 50 souls by January 1908, with complete abandonment following by 1909.

The signs of economic despair were everywhere:

- Stock prices plummeted from $5.25 to under 50 cents per share

- Mining operations ceased, with idle shafts dotting the landscape

- Businesses shuttered, leaving just one saloon operating by early 1908

- The post office—the final vestige of civilization—closed in August 1908

Today, virtually nothing remains of this “monumental mining-stock swindle of the century,” with even the ruins now largely disappeared.

Desert Infrastructure: Building a Town From Nothing

Emerging from the barren desert landscape of eastern California in 1906, Greenwater faced extraordinary logistical challenges that defined its brief existence as a mining boomtown.

You’d pay dearly for water management necessities—$15 per barrel initially, later dropping to $10, with canned tomatoes serving as a cheaper alternative from tent stores.

Construction techniques reflected the settlement’s uncertain future, with most structures built for easy relocation. The Tonopah Lumber Company supplied 150,000 feet of lumber as twenty wooden buildings emerged alongside temporary tents.

Three competing townsites eventually consolidated under the Greenwater Townsite Company, moving operations to the valley floor.

Transportation evolved from footpaths to graded roads, with over 100 freight wagons observed in a single day. The Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad planned a spur line, while essential services—post office, newspaper, and businesses—quickly established roots.

Newspapers and Culture in an Isolated Mining Camp

Beyond the physical infrastructure that sprouted from the harsh desert terrain, Greenwater’s cultural foundation took shape through its newspapers, which became the lifeblood of community identity and commerce. The Greenwater Times launched on October 23rd, followed by the Greenwater Miner, together documenting the town’s evolution while fostering cultural identity in this remote outpost.

- The Times’ pages filled with advertisements from businesses like Greenwater Brokerage Company and Do Drop Inn, revealing the economic pulse of the community.

- Newspaper influence extended beyond information—they shaped perception with Greenwater Townsite Company’s bold claim as “The Greatest Copper City of the Century.”

- Union activities received significant coverage, highlighting the organized labor movement that reached even this isolated desert locale.

- Newspapers warned newcomers about harsh realities of desert life, including critical water shortages.

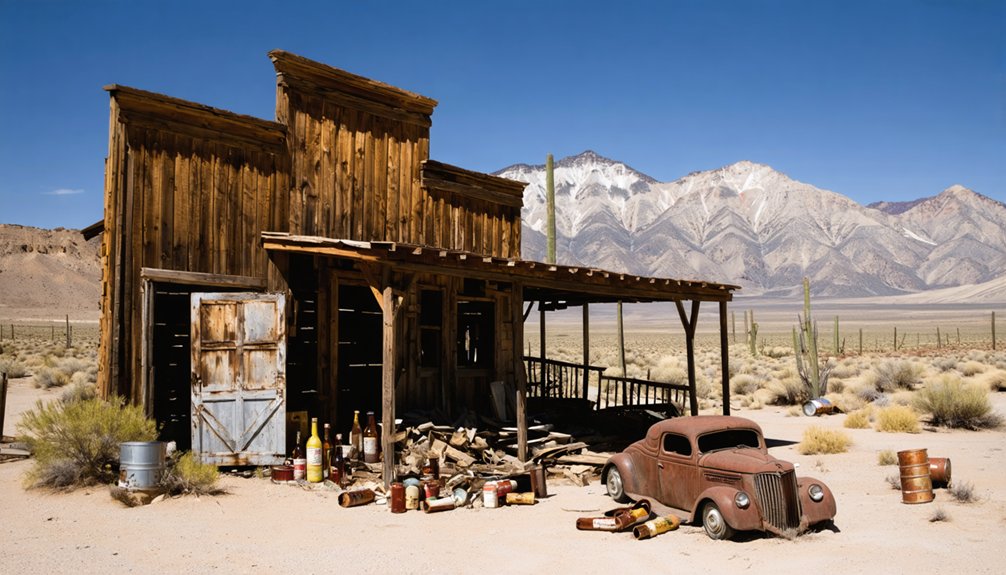

What Remains Today: Visiting Greenwater’s Ghost

Today, when you journey to Greenwater’s former location south of Dante’s View in Death Valley, you’ll encounter a stark reality that challenges historical imagination.

The empty desert where Greenwater once stood speaks volumes about time’s power to erase human endeavors completely.

The ghost town exploration reveals nothing tangible—no standing structures, visible foundations, or interpretive markers commemorate its historical significance.

You’ll reach this remote site via unpaved Greenwater Valley road, where standard vehicles can typically manage, though high clearance may prove beneficial.

The National Park Service acknowledges Greenwater’s existence but confirms no ruins remain visible. Desert winds and time have reclaimed all evidence.

You’re free to wander this undeveloped landscape without restrictions, though you’ll find no amenities or facilities.

Bring your own water, information, and keen eye for the subtle ways nature transforms human ambition into quiet desert once again.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous People Associated With Greenwater During Its Existence?

Yes, you’ll find famous historical figures like steel magnate Charles Schwab, who invested considerably in Greenwater’s mines, and notable residents like Arthur Kunze and Shorty Harris who discovered the original copper deposits.

What Happened to Residents After the Town’s Abandonment?

Drifting desperately after dreams dissolved, you’d have scattered to surviving settlements nearby. Residents’ migration followed predictable patterns—seeking new mining opportunities or stable towns, leaving nothing but ghost town legacy behind.

Did Any Criminal Activity or Lawlessness Plague Greenwater?

You’ll find little evidence of significant criminal activity. Historical records show no organized crime, notable arrests, or high crime rates. The absence of extensive law enforcement reflected low lawlessness rather than lawless conditions.

Were There Any Major Accidents or Disasters in Greenwater?

You won’t find major accident reports or disaster impacts in historical records. Mining hazards existed with deep shafts nearby, but Greenwater’s decline stemmed from economic failure rather than catastrophic events.

How Did Indigenous Peoples Interact With Greenwater’s Mining Community?

You’ll find indigenous peoples had limited cultural exchange with Greenwater miners. Their interactions primarily centered around strained resource sharing, as mining operations disrupted traditional land use and water access, marginalizing native communities in the process.

References

- https://digital-desert.com/greenwater/

- https://www.destination4x4.com/greenwater-california-ghost-town/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ca-greenwaterdistrict/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/california/greenwater/

- https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/nature/greenwater-valley-mining-history.htm

- https://mojavedesert.net/desert-fever/greenwater.html

- https://dvnha.org/info-trip-planning/ghost-towns/

- https://digital-desert.com/greenwater/dv-history.html

- https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/deva/section4c3.htm

- https://adventuretaco.com/greenwater-valley-has-copper-no-silver-no-gold-or-not-blacks-2/