Gwillemville emerged as a mining settlement during Colorado’s Silver Boom, developing into a thriving economic center with over 1,000 workers. Positioned dramatically on a 600-foot cliff, it specialized in zinc-lead extraction until toxic contamination caused its decline around 1923-1925. Now a Superfund site, you can observe this ghost town’s decaying structures from Highway 24 west of Vail, but trespassing is prohibited. The town’s fascinating history intertwines with environmental consequences that continue to shape its legacy today.

Key Takeaways

- Gwillemville was a thriving mining settlement established during Colorado’s Silver Boom in the 1880s within the Jerome Park coal district.

- The town’s economy centered on high-grade silver ore mining and coal production, employing over 1,000 workers at its peak.

- Residents abandoned Gwillemville in 1923-1925 due to health concerns from arsenic and lead contamination and declining mining profits.

- The ghost town sits on a 600-foot cliff and has been designated a Superfund site since 1984 due to toxic environmental contamination.

- Visitors can view Gwillemville’s decayed structures from Highway 24 west of Vail, but direct access is prohibited due to safety concerns.

The Lost Mining Settlement of Gwillemville

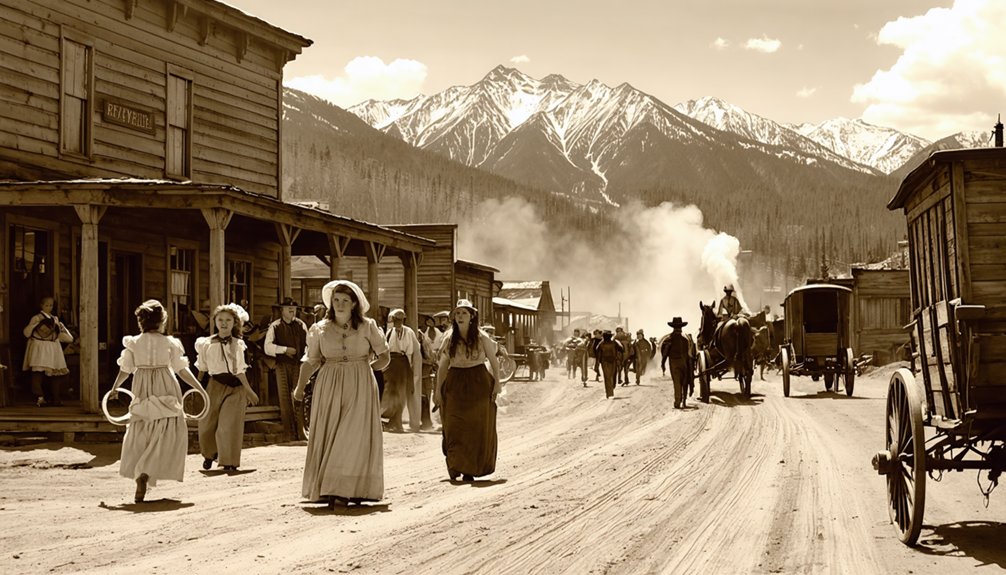

Nestled in the rugged Colorado mountains, Gwillemville emerged as a quintessential mining settlement during the late 19th century, following the pattern of numerous boom-and-bust towns that dotted the western landscape.

You’ll find its remains clustered around what were once productive gold and silver claims, with remnants of cabins, mill sites, and supply depots marking the community’s footprint.

Unlike places preserved in mining folklore, Gwillemville’s story mirrors the harsh reality behind many ghost town legends.

Miners extracted high-grade ore yielding up to 60 ounces of silver per ton through challenging lode mining operations.

Water-powered stamp mills processed these precious metals while seasonal snow dictated operational rhythms.

The town’s prosperity rose and fell with metal prices, ultimately surrendering to the same economic forces that claimed countless Colorado mining communities. At its peak, the settlement operated at a staggering 11,000 feet elevation, similar to other high-altitude mining towns in the San Juan Mountains.

Like nearby Leadville, the town established fair mining regulations to prevent claim disputes and attract more prospectors to the region.

Historical Origins and Discovery

The story of Gwillemville begins with the Colorado Silver Boom that swept through the Rocky Mountains in the 1880s. Prospectors employing rudimentary mining techniques discovered rich mineral veins in this remote, mountainous region, prompting a swift influx of fortune-seekers.

Early settlers established the community around these valuable ore deposits, building a settlement that would soon appear on regional maps. The town’s name likely honored a significant mining investor or local figure, becoming official when the post office opened. Like Gillett, the town was situated at a considerable high elevation with harsh mountain conditions.

Ambitious prospectors transformed virgin mountainside into Gwillemville, immortalizing its namesake through official recognition.

You’ll find Gwillemville’s historical footprint in mining company archives, post office records, and occasional newspaper mentions.

Despite challenging conditions at high elevation with limited access routes, miners and their families persevered, creating a community that flourished briefly before its eventual abandonment. Similar to Gilman’s story, the discovery of zinc in the ore initially posed extraction challenges for the early miners.

Mining Operations and Economic Peak

You’ll find Gwillemville’s mining prosperity centered around its extensive coal operations rather than zinc-lead extraction, with daily production reaching an impressive 1,000 tons during the economic zenith of the 1880s-1890s.

The mining infrastructure evolved to include over 240 coking ovens at the Cardiff plant, representing significant technological investment that transformed raw coal into valuable coke for steel production and other industries. Similar to other Colorado mining regions, the completion of Denver railroad connections facilitated efficient coal shipment and expanded market access.

This industrial expansion created economic prosperity throughout Garfield County, employing over 1,000 workers across mining, coke processing, and railroad operations while establishing crucial market connections to Leadville, Pueblo, and Grand Junction. Unlike the gold dust currency used in saloons during Colorado’s Gold Rush era, Gwillemville’s economy operated primarily on standardized payment systems for its workforce.

Zinc-Lead Extraction Methods

Deep beneath the rugged terrain of Gwillemville, complex zinc-lead extraction operations transformed the small settlement into Colorado’s premier metal producer for several decades.

You’ll find the mining legacy etched into the mountainside where underground shafts and tunnels penetrated the Gore Range’s steep cliffs.

Miners employed selective techniques to target high-grade ore zones, using square-set and shrinkage stoping methods for the narrow, steeply dipping veins.

The extracted material required complex timbering due to unstable rock conditions. For zinc processing and lead recovery, ore traveled via tramways to mills at the canyon’s base, where gravity separation initially dominated.

The New Jersey Zinc Company was instrumental in the area’s development when they consolidated multiple mines into the Eagle Mine in 1912.

Later, flotation processes dramatically improved recovery rates from complex ores. The concentrated minerals were then shipped to off-site smelters for final refinement, completing the extraction cycle that fueled Gwillemville’s economy.

Similar to entries on a disambiguation page, the mining claims in Gwillemville often had multiple names and ownership changes throughout their operational history.

Mining Equipment Evolution

As Gwillemville shifted from primitive extraction to industrial mining, equipment evolution transformed operations throughout the canyon’s network of mines.

You’d witness the change from horse-drawn carts and burros to sophisticated rail systems that efficiently transported ore from deep shafts to processing facilities.

The revolution in mining machinery accelerated when:

- Steam engines gave way to electric hoists and 50 HP motors, allowing shafts to reach depths over 1,000 feet

- Wilfley tables, invented locally by Arthur Wilfley, separated ore particles by density during concentration

- Automated ore dumping systems replaced dangerous manual loading methods, reducing labor costs

Ore processing advanced from crude crushing to multi-stage grinding and concentration methods that reduced ore to 25% valuable metal content, drastically cutting transport costs and improving profitability as Gwillemville’s operations matured.

The milling process typically began with the ore being crushed into fine sand using four distinct types of equipment including the Blake jaw crusher, which was essential for the initial breaking down of raw material.

Miners at Gwillemville often navigated treacherous conditions using pneumatic drills to extract precious metals from the hard quartz veins embedded in the mountain.

Community Economic Prosperity

While Gwillemville’s origins began as a modest mining settlement in the late 1880s, the town rapidly evolved into a thriving economic center within the Jerome Park coal district.

The Grand River Coal and Coke Company drove this prosperity, employing over 1,000 workers who produced up to 1,000 tons of coal daily.

You’d have witnessed remarkable economic diversification as businesses sprouted to serve the growing population—general stores, boarding houses, and saloons flourished alongside mining operations.

Though lacking community resilience due to dependence on coal, Gwillemville’s peak prosperity between 1887 and the early 1900s created a vibrant social fabric with several hundred residents.

The Colorado Midland Railway extension connected this boom town to larger markets in Leadville, Pueblo, and Grand Junction, sustaining its growth until demand waned in the early 20th century.

Daily Life in Gwillemville’s Heyday

During Gwillemville’s peak years, daily life revolved almost entirely around the mining operations that defined this small Colorado community. Your daily routines would have been dictated by long work shifts extracting silver, zinc, and lead from the Eagle Mine.

You’d return to your modest, company-built cabin, designed for practicality rather than comfort, often crowded and poorly insulated against harsh mountain weather.

Social gatherings provided essential respite from grueling labor:

- Evening gatherings at the local saloon for card games and storytelling

- Communal dances organized by fellow residents in multipurpose buildings

- Seasonal celebrations and holidays that fostered community bonds

Despite minimal infrastructure and services, you’d find a strong sense of mutual dependence typical in isolated mining towns, with residents relying heavily on the company store and limited rail connections.

The Decline and Abandonment

You’ll notice Gwillemville’s decline began abruptly in 1923 when tests revealed dangerous levels of arsenic and lead contamination from decades of unregulated mining operations.

Most families left within an eighteen-month period between 1924-1925, abandoning homes and businesses as health concerns mounted and mining profits simultaneously dwindled.

Toxic Mining Remnants

As Gilman’s mining operations expanded throughout the early 1900s, they left a devastating toxic legacy that would eventually contribute to the town’s abandonment.

The extensive zinc extraction processes, which relied on roasting and magnetic separation, generated massive amounts of waste containing heavy metals that seeped into local groundwater and soils.

This toxic legacy created an environmental impact you can still see today:

- Acid mine drainage transformed nearby waterways, dissolving deadly metals into streams

- Vegetation withered from soil contamination, leaving barren, unusable landscapes

- Airborne heavy metals and contamination posed serious health risks to residents

Even after mining ceased in the late 1980s, remediation efforts struggled against the sheer scale of pollution, leaving Gilman uninhabitable and complicating any potential for economic change or redevelopment.

Population Exodus Timeline

While toxic contamination was silently destroying Gwillemville’s environment, its population followed a parallel trajectory of decline.

You’d have witnessed the town’s gradual emptying throughout the mid-20th century as mining profitability waned and the environmental legacy of heavy metals poisoned groundwater and the Eagle River.

The population impact accelerated dramatically in the early 1980s. After Glenn Miller’s purchase briefly kindled hope in 1983, the EPA’s Superfund designation crushed any revival dreams.

By 1984, the agency ordered complete evacuation due to toxic contamination, and June 1985 marked the final exodus as remaining residents departed forever.

The town entrance was chained off, services terminated, and Gwillemville became truly a ghost town—abandoned, contaminated, and locked in legal battles over its poisonous inheritance.

Visiting the Remains Today

Despite being one of Colorado’s most visually striking ghost towns, Gilman remains tantalizingly out of reach for modern explorers.

Gilman stands hauntingly beautiful on Colorado’s cliffs, forever visible yet permanently forbidden to today’s adventure seekers.

You’ll find this former mining community perched dramatically on a 600-foot cliff above Eagle River, visible from Highway 24 west of Vail. As a designated Superfund site since its 1984 EPA closure, trespassing is strictly prohibited and prosecuted.

Your ghost town accessibility options include:

- Pulling over at designated highway viewpoints accessible year-round with standard vehicles

- Observing the decayed structures and mining relics from a safe, legal distance

- Exploring nearby towns like Minturn for amenities while respecting Gilman’s boundaries

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous Outlaws Associated With Gwillemville?

You might expect Wild West tales, but no famous outlaws have historical significance in Gwillemville. Unlike other mining towns where desperados roamed, this Colorado settlement maintained a law-abiding, corporate-controlled mining community.

What Natural Disasters Affected Gwillemville Throughout Its History?

You’d find flood damage from mine tunnel seepage particularly devastating, with contaminated waters turning the Eagle River orange. Fire incidents were secondary concerns compared to the environmental disasters caused by mining activities.

Are There Any Reported Hauntings or Paranormal Activity?

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire. You won’t find documented ghost sightings or paranormal investigations at this location, as records show no verified supernatural activity despite its abandoned, atmospheric setting.

What Happened to Gwillemville’s School and Church Buildings?

You’ll find the church and school buildings have been dismantled, their materials repurposed by locals. These abandoned structures held significant historical value before their eventual demolition in the early 1940s.

Did Gwillemville Have Connections to Native American Tribes?

You’ll find evidence of Native tribes like the Ute, Arapaho, and Cheyenne in the region, though specific cultural exchanges with Gwillemville weren’t documented beyond typical frontier interactions of the 1800s.

References

- https://www.uncovercolorado.com/ghost-towns/gilman/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e07GnE8W9nQ

- https://www.denver7.com/news/local-news/colorado-ghost-towns-their-past-present-and-future-in-the-rocky-mountains

- https://abandonedforgottendecayed.com/2016/07/09/the-abandoned-mining-town-of-gilman-colorado/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilman

- https://www.vailmag.com/news-and-profiles/2019/10/a-look-back-at-gilman

- https://ruralresurrection.com/ghost-towns-gilman-colorado/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CCXuJJiQDfA

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/colorado/summitville/

- https://digitalcommons.du.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4209&context=dlr