You’ll find between 15 and 30 documented ghost towns in Delaware, though there’s no uniform definition for what qualifies as one. Sussex County contains the highest concentration, including iron furnace settlements like Pine Grove Furnace and colonial sites such as Saint Johnstown. New Castle County features Glenville (abandoned after 2003’s Tropical Storm Henri) and Fort Delaware, while Kent County includes hurricane-destroyed Woodland Beach and vanished industrial hub Andrewsville. The exact count depends on whether you’re considering completely vanished settlements, partially abandoned communities, or archaeological remnants—each with distinct histories worth exploring further.

Key Takeaways

- Delaware lacks a uniform definition for ghost towns, making exact counts difficult due to varying classification criteria and incomplete records.

- Sussex County contains the highest concentration, including Banning, New Market, Owens Station, Saint Johnstown, Woodland, and Pine Grove Furnace.

- New Castle County features Glenville, Zwaanendael Colonies, Fort Delaware, and Nemours, each with documented histories and verifiable locations.

- Kent County includes Andrewsville and Woodland Beach, both abandoned due to industrial decline and hurricane damage respectively.

- Most Delaware ghost towns resulted from coastal disasters, industrial shifts, colonial failures, and transportation changes rather than mining decline.

Counting Delaware’s Ghost Towns: The Challenge of Definition

Determining how many ghost towns exist in Delaware requires grappling with a fundamental problem: no uniform definition governs what qualifies as a ghost town.

You’ll find classifications vary wildly by source, complicating any accurate count.

While historians estimate up to 50,000 ghost towns across America, Delaware’s specific tally remains elusive.

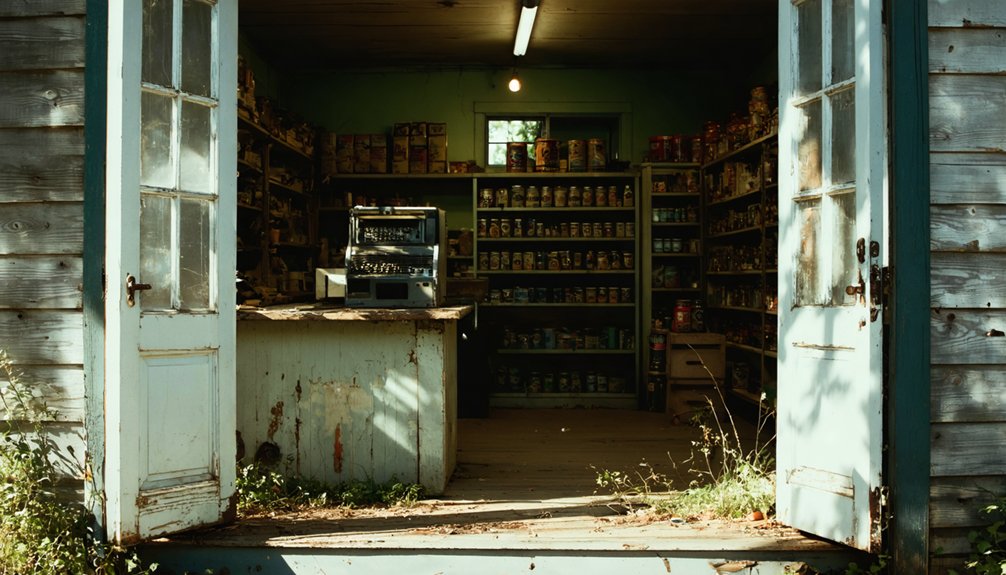

The state’s abandoned sites don’t fit stereotypical images—they’re rooted in manufacturing, fishing, and agriculture rather than mining booms.

Many faded communities still house skeleton populations, blurring the line between thriving and ghost.

Urban exploration reveals hidden landmarks like Nemours within New Castle County’s modern country club, but these sites rarely appear on official lists.

Without standardized criteria distinguishing partial habitation from true abandonment, you’re left relying on incomplete compilations and local knowledge rather than definitive state records.

Ghost town classification depends heavily on whether tangible remains exist for visitors to see, such as abandoned buildings or historic cemeteries.

Some Delaware ghost towns emerged from weather-related disasters, such as Banning in Sussex County, which never recovered after Tropical Storm Henri struck in 2003.

Sussex County’s Forgotten Settlements

Sussex County harbors the densest concentration of Delaware’s ghost towns, with documented settlements including Banning, New Market, Owens Station, Saint Johnstown, and Woodland scattered across its rural landscape. These Sussex settlements represent diverse facets of the county’s forgotten past:

- Industrial Sites: Pine Grove Furnace and Old Furnace on Deep Creek marked Delaware’s iron ore processing heritage before economic shifts rendered them obsolete.

- Rural Crossroads: Bethel declined from a thriving 1700s village to merely a church and cemetery, exemplifying how transportation changes abandoned once-vital junctions. New infrastructure like roads and railways bypassed these settlements, reducing their importance for trade and travel.

- Coastal Communities: Robinsonville southwest of Lewes and settlements near Abbotts Mill reflect agricultural and maritime economies that couldn’t sustain modern populations.

- Colonial Settlements: Zwaanendael was founded in 1631 by Dutch settlers, representing one of the earliest European colonies in Sussex County before its eventual abandonment.

Ghost town preservation efforts remain minimal here, requiring independent research to document these sites before they’re completely erased from collective memory.

New Castle County’s Abandoned Communities

While Sussex County contains Delaware’s highest concentration of ghost towns, New Castle County presents a more complex portrait of abandonment—ranging from colonial-era settlements to twentieth-century communities destroyed by natural disasters.

You’ll find Glenville, a settlement that never recovered from Tropical Storm Henri’s 2003 devastation, abandoned by 2004. Zwaanendael Colony represents Delaware’s first European settlement, now reduced to historical footnotes.

Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, constructed starting 1813 and destroyed by 1831 fire, has transformed from military installation into ghost-hunting destination featured on SyFy’s Ghost Hunters. The fort served as a Civil War prison camp, holding approximately 33,000 Confederate prisoners throughout the war. Similar to Fort Jefferson in Florida, Fort Delaware functioned as both a defense site and prison during the Civil War era.

Nemours, positioned within Dupont Country Club grounds north of Wilmington, stands as another abandoned community.

Unlike Sussex County’s urban legends and old mythology surrounding vanished towns, New Castle’s ghost settlements offer documented timelines and verifiable locations—though their stories remain equally compelling.

Kent County’s Vanishing Towns

You’ll find Kent County’s ghost town record centers on two distinct settlements: Andrewsville, tied to Delaware’s early industrial furnace operations, and Woodland Beach, a coastal community that succumbed to economic shifts and natural forces.

Andrewsville’s history connects to the state’s 18th and 19th-century iron manufacturing corridor, though specific operational dates for its furnace remain undocumented in standard ghost town inventories.

Woodland Beach represents the county’s most consistently cited vanished settlement, appearing across multiple Delaware ghost town catalogs as a primary example of coastal decline tied to fishing industry collapse and hurricane flooding. The area near the old boardwalk site is known for moonlit apparitions that wander where the 1900s-era entertainment district once stood.

Andrewsville’s Forgotten Furnace History

Deep in Kent County’s agricultural heartland, Andrewsville once thrived as a small industrial hub before vanishing from Delaware’s modern maps. This tiny settlement’s industrial relics tell a story of economic ambition that couldn’t withstand changing times.

Evidence of Andrewsville’s Industrial Past:

- Furnace remnants suggest metalworking operations existed here, though precise operational dates remain undocumented in available historical records.

- Kent County location placed it within Delaware’s agricultural zone, where small manufacturing operations supplemented farming economies throughout the 19th century.

- Complete abandonment occurred as industrial consolidation drew workers toward larger manufacturing centers, leaving behind only structural traces and archival mentions. The Delaware Railroad connected Porter to Seaford starting in 1855, establishing new trade routes that bypassed smaller settlements like Andrewsville. Similar to other abandoned industrial towns, the decline was rapid once primary economic activities ceased and funding to sustain operations disappeared.

You’ll find Andrewsville listed in historical registries as a Kent County hamlet, yet physical evidence of its furnace operations has largely disappeared beneath farmland.

Woodland Beach’s Coastal Decline

When Woodland Beach emerged as Delaware’s premier coastal resort during the 1880s, few could have predicted that nature would twice rewrite its destiny. The October 1878 hurricane sent a ten-foot tidal wave crashing across 35 miles of coastline, destroying the town’s hotels, pavilions, and steamboat infrastructure.

You’d witness determined investors rebuild everything—boardwalks, orchestras, and daily Thomas Clyde steamboat service from Philadelphia.

The reconstructed resort thrived until 1914, when a winter nor’easter delivered the final blow. Coastal erosion and infrastructure devastation proved insurmountable this time. The steamboat pier vanished, buildings crumbled, and tourism decline became permanent.

Today, you’ll find a quiet fishing village where photographers chase Delaware Bay sunrises—a frozen moment replacing what was once Delaware’s top coastal destination. Only a handful of residents remain in what historians now recognize as one of Delaware’s lost towns.

Colonial Failures and Early Massacres

Delaware’s colonial landscape bears the scars of ambitious settlements that crumbled under the weight of intercultural conflict, disease, and economic collapse. You’ll find evidence of these failures throughout the region’s archaeological record, where Native rebellions and colonial massacres left entire communities abandoned.

Three primary factors destroyed early Delaware settlements:

- Violent territorial disputes between Swedish, Dutch, and English colonizers created unstable conditions that forced settlers to flee established towns.

- Indigenous resistance movements targeted vulnerable outposts, particularly during the 1640s-1660s conflicts over land encroachment.

- Economic isolation combined with epidemic diseases decimated populations faster than reinforcements could arrive.

These colonial massacres and subsequent retaliations transformed promising settlements into abandoned ruins. Understanding this violent foundation helps you comprehend why certain Delaware communities vanished completely, leaving only fragments in historical documents.

Iron Furnaces and Mining Communities That Disappeared

Throughout the mid-18th century, iron furnace operations transformed Sussex and Kent Counties into industrial hubs before economic forces erased them from Delaware’s landscape.

Pine Grove Furnace, also called Deep Creek Furnace, operated around 1750 and earned National Register recognition in 1977 for its historical significance.

The iron industry once employed hundreds at these sites, where enslaved workers performed hazardous smelting tasks under brutal conditions.

Military Fortifications Left to Decay

Beyond the vanished iron furnaces, Delaware’s landscape harbors another category of abandoned sites—military fortifications that once guarded the Delaware River and Bay. You’ll discover these military relics scattered along Delaware’s coastline, remnants of coastal defenses spanning from the 1750s through World War II.

Three Major Abandoned Fort Sites:

- Fort DuPont – Originally built 1863-1864, disarmed and scrapped by 1942. It was later converted to a state park in 1992.

- Fort Saulsbury – Constructed between 1917-1920 near Slaughter Beach, officially deactivated in 1946.

- Fort Miles – Served as Delaware’s primary coastal defense from 1941-1945, with weapons scrapped by 1948.

Most Delaware Bay defenses were abandoned by 1946 after minimal wartime action. Harbor defenses officially inactivated in March 1946.

This left concrete batteries and fire control towers vulnerable to coastal erosion and decay throughout the region.

Natural Disasters That Created Modern Ghost Towns

While military abandonment shaped Delaware’s coastal landscape through the mid-20th century, natural disasters delivered more sudden blows that transformed thriving communities into uninhabitable ruins. Unlike volcanic eruptions or tsunami destruction that devastate other regions, Delaware’s ghost towns fell to hurricanes and floods.

Delaware’s ghost towns emerged not from fire or earthquake, but from the relentless assault of hurricanes and floods.

Tropical Storm Henri and Hurricane Isabel struck Glenville in 2003, destroying structures throughout New Castle County. Most residents evacuated by 2004, never returning.

Woodland Beach in Kent County faced similar abandonment after repeated storm damage left the coastal settlement uninhabitable. Even Delaware’s earliest European presence, Zwaanendael Colony in Sussex County, succumbed partly to environmental hazards.

These disasters didn’t just damage buildings—they eliminated the economic viability that kept communities alive, forcing permanent evacuations where recovery became impossible.

Historic Transportation Hubs Bypassed by Progress

Delaware’s railroad revolution began in 1855 when the Delaware Railroad opened its first line from Porter to Seaford, fundamentally altering the state’s settlement patterns.

By 1859, connections reached Delmar, spawning communities like Greenwood in 1858.

This railroad architecture created economic centers that later became ghost towns when transportation policy shifted toward highways.

The decline followed a predictable pattern:

- Initial Boom (1855-1900s): Towns like Owens Station emerged as essential hubs, with the Queen Anne’s Railroad linking Baltimore to New Jersey.

- Consolidation Era: Pennsylvania Railroad absorbed smaller lines, operating the Junction & Breakwater route between Lewes and Rehoboth.

- Abandonment (1960s-1970s): Trucks replaced freight trains, and passenger services ended, leaving 5.5 miles of abandoned track now converted to rail trails.

Communities that depended on rail commerce simply vanished when tracks were removed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Visitors Legally Explore Delaware’s Ghost Towns and Abandoned Sites?

You’ll find daring exploration varies by location—most historic landmarks require landowner permission before visiting. Delaware’s ghost towns sit on private property, so you must verify access rights. Fort Delaware and Gibraltar Mansion welcome public visitors legally.

Are Any of Delaware’s Ghost Towns Considered Haunted or Have Paranormal Activity?

Delaware’s documented ghost towns lack direct haunted legends or paranormal sightings in archival records. However, you’ll find abundant paranormal activity reported at separate abandoned sites like Old Gumboro Homestead and Black Diamond Road, built on Native American burial grounds.

What Artifacts Have Been Recovered From Delaware’s Abandoned Settlements?

You’ll find historical artifacts like iron mining tools at Iron Hill Museum and maritime rescue equipment at Fenwick Island’s Life-Saving Station. However, archaeological discoveries from Zwaanendael Colony remain largely unrecovered, with most settlement sites yielding minimal documented artifacts.

How Does Delaware Preserve or Protect Its Ghost Town Locations?

Delaware’s historical preservation efforts for ghost towns remain limited and decentralized. You’ll find some sites like Gibraltar Mansion’s gardens actively restored, while most locations lack formal protection programs, requiring local research to identify and safeguard cultural heritage independently.

Which Delaware Ghost Town Offers the Best-Preserved Structures for Photography?

Like frozen frames in time’s album, you’ll find Gibraltar Mansion’s abandoned architecture offers Delaware’s most photogenic ruins. Historical preservation efforts since 1997 haven’t erased its haunting beauty—wisteria-wrapped walls and intact staircases create compelling compositions for your independent exploration.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Delaware

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Delaware

- http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/history/usa/de.htm

- https://ghost-towns.close-to-me.com/states/delaware/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ex8Hld_imPU

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UAkxBOSLhs

- https://www.visitkeweenaw.com/listing/delaware-the-ghost-town/515/

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/delaware/abandoned-places-delaware

- https://westernmininghistory.com/664/what-is-a-ghost-town-wmh-town-classifications-explained/