Oregon holds the distinction of having the most ghost towns in America, with over 256 documented sites scattered from the high desert to coastal ranges. These abandoned settlements emerged between the 1847 Land Act and the 1920s, fueled by gold rushes, timber booms, and wool trading. You’ll find the highest concentrations in Baker, Grant, and Wallowa counties, where resource depletion and economic shifts left entire communities empty. Below, you’ll discover the stories behind these vanished towns and how to explore them safely.

Key Takeaways

- Oregon has 256 documented ghost towns, the highest number of any U.S. state.

- Statewide estimates suggest over 200 ghost towns exist across Oregon.

- More than 80 Oregon ghost town sites are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Baker County leads with 9 ghost towns, followed by Grant, Wallowa, Jackson, and Josephine counties.

- These towns span from 1847 Land Act settlements to 1920s company towns, primarily from mining and lumber industries.

The Total Number of Ghost Towns Across Oregon

According to Professor Stephen Arndt‘s extensive survey, Oregon contains 256 documented ghost towns—the highest concentration of any state in the nation.

You’ll find this impressive count stems from the state’s frontier legacy, where mining strikes and lumber operations created temporary settlements across the wilderness. Several historians corroborate estimates exceeding 200 ghost towns statewide, with over 80 earning spots on the national register through historic preservation efforts.

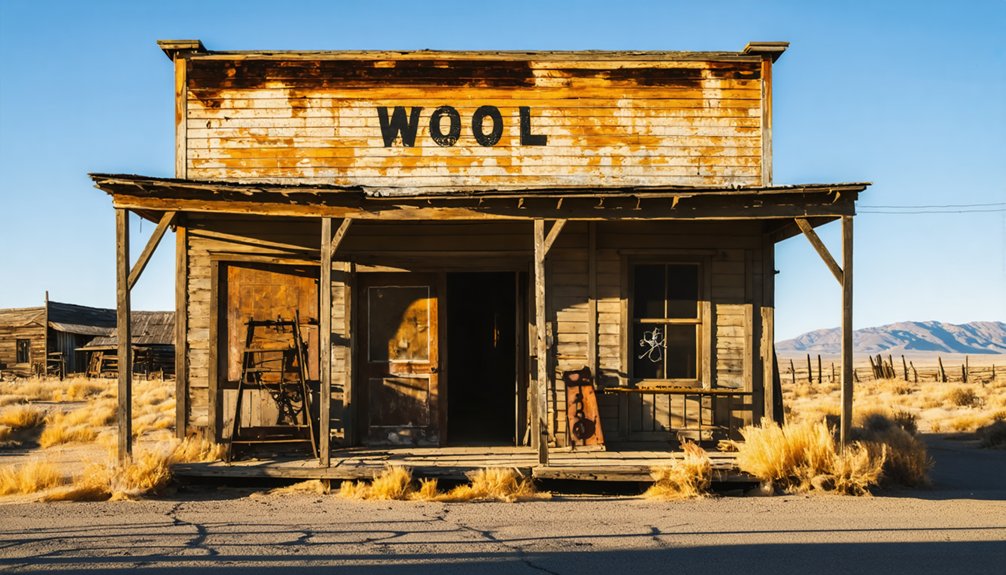

These abandoned communities range from iconic tourist attractions like Shaniko’s wool-trading center to obscure mining camps scattered throughout remote valleys. The sheer volume—spanning from 1847 Donation Land Act claims to 1920s company towns—makes visiting every site nearly impossible.

You’re looking at remnants representing Oregon’s resource extraction economy, where boom-and-bust cycles left architectural evidence of communities that once thrived independently. Towns experienced rapid growth during resource booms such as gold prospecting, wool trading, and lumber operations, only to decline when natural resources were exhausted or transportation routes shifted. These ghost towns are classified by varying degrees of abandonment, from sites with no apparent remains marked only by cemeteries to fully restored settlements now serving as state parks.

What Caused So Many Oregon Towns to Become Abandoned

While Oregon’s 256 ghost towns share a common fate of abandonment, their demise stemmed from five interconnected forces that shaped the state’s settlement patterns between the 1850s and 1950s.

Resource exhaustion devastated single-industry settlements—Waldport West’s sawmill closed in 1938 after accessible timber vanished, while Bohemia’s gold reserves ran dry.

When the resources ran out, entire communities vanished—timber towns and mining camps alike couldn’t survive without their economic lifeblood.

Economic shifts proved equally ruthless; the Great Depression emptied communities by mid-1940s, and railroad bypasses doomed crossroads towns like Peak around 1918.

Natural disasters struck swiftly—the 1948 Columbia River Flood obliterated Vanport, displacing 18,000 residents overnight.

Industry declines accelerated abandonment as old-growth forests disappeared and mining operations turned unprofitable.

Environmental restrictions further contributed to closures, compounding the challenges faced by resource-dependent communities in Oregon’s lumber regions.

Many of these settlements were built by international settlers seeking fortune, drawn to Oregon’s abundant natural resources and economic opportunities.

Today, these preservation challenges create eco tourism opportunities, letting you explore Oregon’s authentic frontier history through weathered structures and forgotten cemeteries that document western settlement’s boom-and-bust reality.

Which Oregon Counties Have the Most Ghost Towns

Baker County claims the highest concentration with 9 documented ghost towns, rooted in its 1860s gold rush that spawned settlements like Sumpter and Greenhorn across its mountainous terrain.

Eastern Oregon’s mining belt extends through Grant and Wallowa counties, where extraction booms created temporary population centers that collapsed with depleted ore deposits.

You’ll find Granite (1867) and Susanville (1864) among Grant County’s abandoned sites, while the remote geography of these eastern counties preserved structural remnants that coastal settlements lost to development pressure. Cornucopia alone produced $20 million in gold during its peak before declining significantly by the 1970s.

Southern Oregon contributes notable ghost towns in Jackson and Josephine counties, with Buncom founded by Chinese miners in 1851 and Golden emerging from the 1840s gold rush as a peaceful woodland settlement.

Baker County Mining Legacy

Deep in Oregon’s northeastern corner, the rugged peaks and valleys of Baker County conceal one of the state’s richest concentrations of abandoned settlements. Gold rushes transformed this remote territory during the 1880s, spawning towns like Cornucopia—which alone produced 66% of Oregon’s gold by 1939—and Bourne, where 1,500 fortune-seekers carved communities from wilderness.

You’ll find evidence of their ambition in 36 miles of tunnels still threading through mountainsides, remnants of operations that extracted $18 million in precious metals before federal wartime closures ended the boom in 1942.

The shift from placer to lode mining created lasting infrastructure: electrified mills, cable trams, and horizontal shafts that accessed veins more reliably than neighboring districts. Originally known as Cracker City, Bourne was renamed in 1900 after Massachusetts lawyer Jonathan Bourne. The town’s name itself references the horn of plenty, drawing from ancient mythology’s symbol of prosperity and abundance that miners hoped to discover in these mountains. Today, rusty ore carts and rotting timbers mark where entire populations once labored beneath unforgiving peaks.

Eastern Oregon Ghost Concentration

Beyond Baker County’s mining corridors, Eastern Oregon’s high desert sprawl harbors the state’s densest concentration of abandoned settlements—over 200 ghost towns scatter across counties where gold strikes, wool markets, and stagecoach routes once sustained isolated populations.

You’ll find distinct regional clusters worth exploring:

- Wasco County: Shaniko (1901-1911) preserves wool-era structures resisting urban decay

- Umatilla/Gilliam: Hardman and Lonerock mark ranch service hubs along Highway 395

- Malheur County: Remote Danner, Arock, and Rome anchor southeastern stagecoach corridors

- Jackson County: Four documented sites including operational Pinehurst school

- Sherman County: A-class preservation sites overlapping Wasco’s northern boundary

Historical preservation varies dramatically—from Shaniko’s maintained facades to Malheur’s crumbling pioneer outposts. Milikin became a ghost town in 2005 after its last store closed, following decades of decline triggered by a 1988 robbery and murder that scattered its remaining residents. Visitors should consult local historical societies for verification of site accessibility and detailed background information before planning expeditions.

Remote backroads connect these frontier remnants, offering unregulated access to Oregon’s abandoned past.

Wallowa and Grant Highlights

Where Wallowa and Grant counties converge along the Blue Mountain ridgeline, two distinct ghost town narratives emerge from Oregon’s mineral-rich interior.

You’ll find Wallowa’s lumber legacy at Maxville, established in 1923 and abandoned by 1933, where nothing remains of Oregon’s only African American company town that once housed 15% minority residents.

Grant County showcases earlier gold rush sites—Greenhorn’s seven standing homes date to 1860s prospecting, while Susanville and Galena preserve 1864-1865 mining camps as type B and C classifications.

Ghost town preservation efforts face abandoned building materials challenges across both regions.

Zumwalt’s 2009 documentation captures deteriorating structures, while Flora maintains iconic status despite sparse population.

You’re exploring territories where mineral extraction and timber processing created communities that vanished when resources depleted, leaving skeletal remnants throughout Eastern Oregon’s remote landscape.

Famous Ghost Towns Worth Exploring

Oregon’s most accessible ghost towns cluster along historic mining and transportation corridors, each preserving distinct chapters of the state’s boom-and-bust frontier economy. You’ll find authentic remnants of pioneer life without manufactured tourism experiences.

Top destinations for independent exploration:

- Shaniko – Wasco County’s wool shipping capital showcases urban decay with rusted trucks and weathered buildings; 30 residents host annual events.

- Sumpter – Baker County’s gold town offers hands-on panning at the Sumpter Valley Dredge; gateway to Bourne, Granite, and Greenhorn.

- Golden – Oregon State Heritage Site preserving 1840s mining structures in Josephine County.

- Buncom – May’s Buncom Day Festival funds ghost town preservation through community support.

- Hardman – Morrow County’s agricultural hub displays multiple historical identities across northern grasslands.

Each site rewards visitors who venture beyond sanitized attractions.

Understanding the Different Categories of Ghost Town Preservation

Ghost town classification systems reveal how preservation experts assess site integrity and historical value across Oregon’s abandoned settlements. You’ll find Class A through E rankings measure everything from barren sites to partially populated communities.

Class F designations identify restored locations like Golden, where state intervention combats preservation challenges through Parks and Recreation Department oversight.

Ghost town economics shift dramatically when communities evolve from abandonment to tourist attractions—Buncom’s annual May festival demonstrates how minimal populations sustain heritage sites.

True preservation requires understanding whether you’re encountering completely abandoned ruins or maintained historical structures. Sites receiving National Register status, like Golden since 2002, balance authentic decay against public access needs.

Oregon’s classification framework helps you distinguish between naturally reclaimed landscapes and actively curated heritage properties, each representing different approaches to conserving frontier history.

Shaniko: The Wool Capital That Time Forgot

You’ll find Shaniko’s remarkable story begins in 1903 when it earned the title “Wool Capital of the World” after three record-breaking sales totaling an estimated five million dollars annually by 1904.

The Columbia Southern Railroad’s terminus brought prosperity to this central Oregon hub until 1911, when the Oregon Trunk Railway’s competing route up the Deschutes River Canyon diverted commerce away from the town—a blow compounded by devastating fires in 1910 and 1911 that destroyed much of the business district.

Today, roughly 23 residents maintain this National Register site, where the recently refurbished Shaniko Hotel and seasonal shops attract up to 400 visitors during August weekends.

The Shaniko Preservation Guild hosts events like the annual Wool Gathering amid authentic boardwalks and original sheep sheds.

Rise of Wool Empire

When the first train rolled into Shaniko on May 13, 1900, it transformed a modest stagecoach stop into Oregon’s most ambitious wool-trading empire. The Dalles businessmen envisioned something unprecedented—a railroad terminus that’d channel central Oregon’s wealth through their warehouses.

Infrastructure rose from desert dust with remarkable speed:

- B.F. Laughlin and W. Lord’s warehouse became Oregon’s largest, storing 4 million pounds of wool.

- The Shaniko Hotel’s 18-inch handmade brick walls still stand against urban decay, earning National Register status.

- A 10,000-gallon wooden water tower pumped life from Cross Hollow Canyon.

- Three annual wool sales drew ranchers from Burns to California.

Historic preservation efforts now protect the 1900 structures.

Railway’s Devastating Impact

The Oregon Trunk Railway’s completion through Deschutes River Canyon in 1911 shattered Shaniko’s monopoly on central Oregon commerce with surgical precision. James J. Hill’s direct Portland-to-Bend route diverted 70% of freight traffic overnight, transforming your once-thriving wool capital into a dead-end terminus.

The Columbia Southern Railway couldn’t compete—passenger service ended by the early 1930s, with complete abandonment following 1964’s catastrophic floods near Grass Valley.

Compounding fires in 1910-1911 destroyed 80% of downtown, including critical wool storage facilities. Population plummeted from 600 to 124 within a decade.

Modern-Day Attractions and Events

Despite its official 1959 ghost town designation, Shaniko maintains a pulse through 20-25 year-round residents who’ve transformed abandonment into preservation.

The Shaniko Preservation Guild operates museums within historic structures, ensuring architectural authenticity remains intact.

You’ll discover these modern attractions:

- Shaniko Hotel: Reopened August 2023 after extensive refurbishment, listed on the National Register of Historic Places

- Ghost town festivals: Annual Wool Gathering, Tygh Valley Bluegrass Jamboree, and Ragtime Festival draw 400+ visitors on August weekends

- Imperial Stock Ranch: Offers tours featuring hand-crafted meats, yarn, and wool apparel (their yarn clothed 2014 Olympic Team USA)

- Summer shops: Antiques dealers and End of the Trail Ice Cream operate seasonally

- Preservation efforts: Wood-plank sidewalks and false-front buildings maintain authentic Old West character

Highway 97 travelers consistently stop for photography and historical immersion.

Sumpter and Its Gold Mining Heritage

In 1862, five prospectors from South Carolina struck gold near Cracker Creek in Oregon’s Blue Mountains, setting off a rush that would transform the Sumpter Valley into one of the state’s most productive mining districts.

You’ll find the valley’s landscape permanently altered by three massive Yuba-style dredges that operated between 1913 and 1954, collectively extracting $10-12 million in gold.

The final dredge, Sumpter No. 3, weighed 1,250 tons and processed 9 cubic feet of material per minute using 72 one-ton buckets.

This mining technology revolutionized gold recovery, but its environmental impact remains visible today—miles of tailings stacks document the transformation.

After a devastating 1917 fire and the railroad’s 1947 closure, Sumpter declined.

The preserved dredge now anchors a state heritage area where you can explore this industrial archaeology.

Lesser-Known Ghost Towns Off the Beaten Path

Beyond the well-documented mining centers like Sumpter, Oregon’s vast southeastern desert conceals dozens of settlements that vanished as quickly as they emerged from the sagebrush plains.

You’ll find authentic ghost town architecture standing silent along seldom-traveled highways, where weathered post offices and stagecoach stops remain untouched by tourist crowds.

These forgotten communities demand your commitment:

- Andrews exists as a true ghost town with zero permanent residents and crumbling historic structures

- Rome sits near the Pillars of Rome, a 100-foot geological formation spanning five miles

- Millican offers the closest registered ghost town to Bend, just 26 miles east

- Golden challenges adventurers with only four original buildings surviving in extreme remoteness

- Waldport West hides 10 miles inland through winding Coast Range forest roads

Locals share Native legends and settlement stories that archival records never captured.

Planning Your Oregon Ghost Town Adventure

Your exploration of Oregon’s 256 documented ghost towns demands careful preparation before you venture onto remote desert highways and mountain backroads.

Pack essential supplies including fuel, paper maps, and provisions—cellular service disappears quickly in eastern Oregon’s high desert.

Highway 207 provides access to multiple mining sites, while Sterling Creek Road leads to Sterlingville’s 1863 cemetery where ghost town legends persist.

Research Stephen Arndt’s classifications and Gary Speck’s documentation before departure.

Towns like Condon offer final supply points near haunted landmarks such as Hardman and Lonerock.

Winter snows close mountain routes to sites like Granite and Sumpter, so plan visits between May and October.

Download offline maps and notify someone of your itinerary when exploring Oregon’s most isolated historical settlements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Oregon’s Ghost Towns Safe to Visit and Explore?

Many Oregon ghost towns are safe to visit as designated tourist attractions with historical preservation efforts. You’ll find accessible sites like Shaniko and Sumpter welcoming exploration, though remote locations require caution regarding structural decay and limited emergency services nearby.

Can You Take Artifacts or Souvenirs From Ghost Town Sites?

No, you can’t legally take artifacts or souvenirs from Oregon’s ghost towns. With over 80 sites federally protected, artifacts legality is strict—souvenir policies prohibit removals under state law and the 1906 Antiquities Act, risking $10,000 fines.

Which Ghost Towns Allow Overnight Camping or Accommodations?

You won’t find overnight camping at Golden Ghost Town, but you’ll discover nearby Wolf Creek Campground. Most Oregon ghost town histories emphasize day-use preservation efforts, protecting these sites while letting you explore freely during designated hours.

Do You Need Permits to Visit Ghost Towns on Private Property?

You’ll absolutely need permission—not just a casual nod—to explore Oregon’s private property ghost towns. Written permits from landowners aren’t legally required but prove essential when trespassing charges loom. Skip the paperwork, risk arrest, fines, and immediate removal from historic sites.

What’s the Best Season to Visit Oregon’s Ghost Towns?

Late summer through early fall offers you the best conditions for exploring Oregon’s ghost towns. You’ll find clear seasonal weather, accessible scenic routes through high desert terrain, and preserved structures—all without winter’s snow blocking your path to forgotten settlements.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oregon

- https://www.deviantart.com/austinsptd1996/journal/Six-Iconic-Ghost-Towns-Within-Oregon-1109696435

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Oregon

- https://www.visitoregon.com/oregon-ghost-towns/

- https://www.pdxmonthly.com/travel-and-outdoors/oregon-ghost-towns

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBCOeX8_ItY

- http://www.photographoregon.com/ghost-towns.html

- https://traveloregon.com/things-to-do/culture-history/ghost-towns/

- https://theashlandchronicle.com/oregon-has-an-abandoned-town-that-most-people-dont-know-about/

- https://lostoregon.org/2019/09/20/rust-rot-ruin-stories-of-oregon-ghost-towns/