You’ll find Jackson’s ghost town remains in Box Elder County, Utah, west of the Great Salt Lake. This former railroad siding served as the western terminus of the Lucin Cutoff line until a catastrophic dynamite explosion in 1904 destroyed everything within a half-mile radius. Today, you can explore deteriorating rail beds, concrete foundations, and scattered mining artifacts amid the desert landscape. The site’s dramatic history reveals more than meets the eye.

Key Takeaways

- Located in Box Elder County, Utah, Jackson was a railroad siding and mining community west of the Great Salt Lake.

- The town served as the western terminus of the Lucin Cutoff line and supported local mining operations in the late 1800s.

- A catastrophic dynamite explosion in 1904 destroyed most of the town and displaced its 45 residents.

- Today, only scattered foundations, mining remnants, and railroad artifacts remain visible in the desert landscape.

- The site features deteriorating infrastructure, including old shacks, a vault structure, and mine shafts with tailings piles.

The Birth of a Railroad Siding

While countless Western towns emerged from mining rushes or homesteading, Jackson’s story began purely as a railroad siding in Box Elder County, Utah.

You’ll find its strategic location just west of the Great Salt Lake, positioned at the western terminus of the Lucin Cutoff line, where it played an essential role in railroad history.

The siding got its name from a local prospector influence – a mine operator who worked the area.

Unlike typical frontier settlements, you won’t find traces of early commercial districts or residential developments here. Instead, Jackson served a singular purpose: providing a spot where trains could pass or be stored along the expanding network of Southern Pacific and Union Pacific lines. Construction began in 1871 as part of Utah’s growing railroad infrastructure.

Jackson stands as a pure railroad artifact – no shops, no homes, just tracks where trains met in Utah’s expanding rail network.

The area saw rapid development with track-laying progress reaching half a mile per day in early construction phases.

It became a vital part of Utah’s mineral transportation system during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Life in the Western Desert

As residents of Jackson confronted the harsh realities of Utah’s western desert, they faced daily temperatures that could soar above 100°F in summer and plummet below freezing in winter.

Desert survival meant adapting to dramatic temperature swings between day and night, while coping with humidity levels as low as 36% in July.

You’d find the townspeople making arid adaptations in every aspect of their lives – from their shelter designs that maximized shade and airflow to careful water management practices.

They’d battle persistent challenges like dust storms and respiratory issues while dealing with the isolation of desert living.

Their homes and businesses required strategic planning for food and water logistics, as the surrounding landscape offered little beyond drought-resistant sagebrush and juniper.

Limited resources and difficult transportation made self-reliance essential in this unforgiving environment. Living in the Great Basin desert region meant enduring both extremely hot summers and bitterly cold winters.

The harsh conditions were exacerbated by the area receiving less than 5 inches of annual rainfall, making water a precious commodity.

The Great Dynamite Disaster

Beyond the daily struggles of desert life, a catastrophic event would forever alter Jackson’s destiny. On February 19, 1904, two Southern Pacific trains collided on the Lucin Cutoff line, detonating a car loaded with dynamite. The explosion’s devastating force obliterated everything within a half-mile radius, catching officials off guard with its sheer destructive power.

You’ll find no trace of the original town today – the blast’s concussion wave pulverized buildings, scattered debris across the desert, and displaced most of Jackson’s 45 residents. Like other places named Jackson across America, this Utah town held historical significance before its destruction. The devastation was particularly notable as it destroyed one of the many small American towns that shared this common place name.

This catastrophic accident exposed critical flaws in dynamite safety protocols for rail transport, leading to stricter regulations. The explosion’s aftermath proved too severe for the tiny community to overcome, ultimately transforming Jackson into one of Utah’s haunting ghost towns.

Railroad Operations and Mining Activities

Before the devastating dynamite explosion of 1904, Jackson served as a strategic railroad siding on the western end of the Lucin Cutoff, supporting both rail operations and regional mining ventures.

You’d find essential infrastructure here, including water stops, fuel stations, and horse stalls with feed troughs – all crucial for maintaining continuous rail service across Utah’s harsh desert landscape.

Jackson’s railroad significance stemmed from its role in mining transportation, named after a local prospector who operated a nearby mine. The local labor force worked diligently on grading and laying rails, following the established pattern of frontier railroad construction.

The snow transport methods were commonly used in winter to move railroad ties and timber through the area. The siding facilitated the movement of timber, railroad ties, and valuable ores throughout the region.

While no major town developed at the site, Jackson’s position along the Lucin Cutoff made it an important logistical point for both the railroad’s expansion and the area’s mining operations during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Daily Life in Early Jackson

Life in early Jackson revolved around more than just its railroad and mining operations. You’d find residents living in simple wooden cabins, built from local timber and designed to withstand Utah’s harsh winters. Daily routines centered around communal living, with neighbors supporting each other through bartering and shared resources.

While miners descended into the depths, others kept the town running through essential trades like blacksmithing and carpentry. Small farms and gardens dotted the landscape, while livestock barns provided shelter for vital work animals. Similar to towns like Saro Gordo which yielded $500 million in minerals, Jackson’s mines drove the local economy.

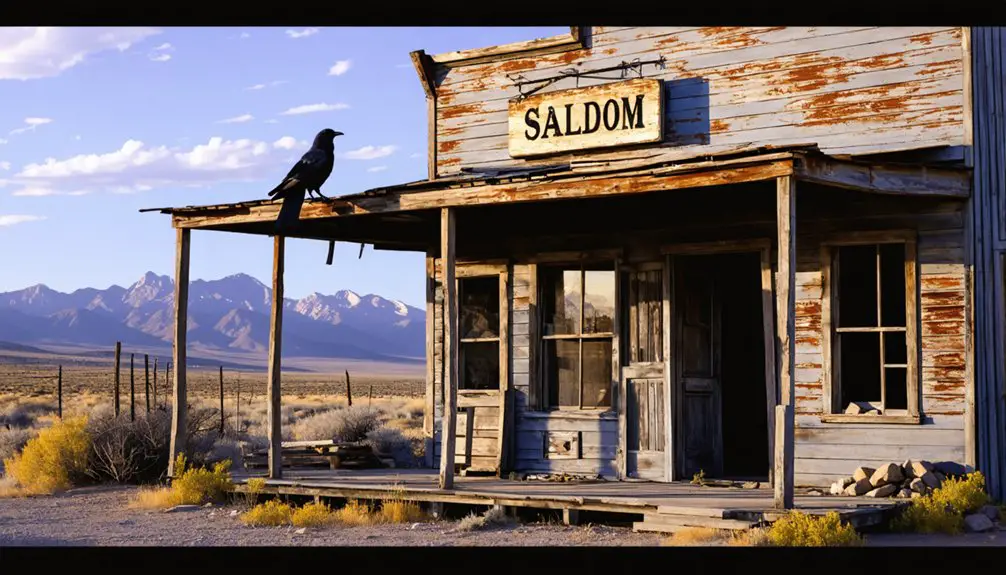

The town’s social fabric wove through its saloons and multi-purpose buildings, where you’d catch up on local news or attend religious gatherings. Despite the isolation and environmental challenges, Jackson’s residents created a self-sustaining community where both legitimate businesses and red-light districts coexisted. Like many mining towns, powder houses were built at a safe distance to store explosives.

The Town’s Slow Decline

While Jackson’s early prosperity hinged on its railroad and mining activities, a catastrophic event in 1904 marked the beginning of its decline. When two Southern Pacific trains collided, causing a devastating dynamite explosion that destroyed everything within a half-mile radius, the town’s fragile community resilience was put to the ultimate test.

You’ll find that Jackson’s isolation in Box Elder County’s western desert made recovery particularly challenging. The town’s economic stagnation intensified as mining yields decreased and railroad traffic diminished.

With only 45 residents at its peak and limited options for diversification in the harsh desert environment, Jackson couldn’t sustain itself. The lack of agricultural possibilities and the high costs of rebuilding in such a remote location ultimately led to its abandonment, transforming this once-bustling railroad siding into the ghost town you’ll discover today.

What Remains Today

If you visit Jackson’s former townsite today, you’ll find virtually no remaining structures due to the devastating 1904 train explosion and subsequent desert reclamation.

The remote location in western Box Elder County reveals only desert terrain typical of Utah’s Great Salt Lake region, with natural processes having erased most traces of human habitation.

The site lacks historical markers or preserved infrastructure, making it challenging to distinguish from the surrounding desert landscape near the Lucin Cutoff.

Physical Site Features

Today’s visitors to Jackson’s ghost town ruins will find several partially intact structures scattered across the harsh Utah desert landscape.

You’ll discover the remnants of classic ghost town architecture, including old shacks with tin roofs and a formidable vault structure distinguished by its windowless, heavy walls that once protected precious metals.

Among the mining camp features, you’ll notice a unique underground building with thick walls, designed specifically for storing explosives and dynamite.

Throughout the site, collapsed walls and foundations outline where buildings once stood, while metal debris and stone rubble tell the story of the town’s violent past, including the devastating 1904 dynamite explosion.

Modern water bottles scattered among historical remnants serve as stark reminders of ongoing visitor impact.

Railroad Infrastructure Remnants

Along the western end of the Lucin Cutoff, you’ll find the deteriorating remnants of Jackson’s railroad infrastructure, including sections of the original siding and rail bed.

While the main line remains active, abandoned switch points and spur tracks that once served mining operations now lead nowhere, telling tales of busier times.

You can spot concrete foundations of former water towers and cisterns that once serviced steam locomotives, along with traces of old pipelines and troughs.

Railroad artifacts litter the area – from rusted rails and spikes to mechanical switch components.

The site’s most dramatic transformation occurred in 1904 when a dynamite car explosion destroyed much of the original infrastructure within a half-mile radius.

Today, scattered ruins of crew quarters and maintenance sheds mark where this once-vital railroad stop operated.

Mining Area Traces

Moving beyond the railroad remains, Jackson’s mining heritage stands frozen in time through scattered physical evidence across the desert landscape.

You’ll find foundations of ore processing mills and bunkhouses dotting the terrain, while collapsed timber frames and rusted metal tell tales of past mining techniques.

Fenced-off mine shafts and adits pierce the hillsides, with massive tailings piles marking the scale of mineral extraction.

The environmental impact remains visible today, with terraced hillsides and open cuts scarring the natural terrain.

Areas once stripped for mining show limited environmental restoration, as sparse vegetation struggles to reclaim disturbed soil.

You can trace old drainage ditches and spot artifact clusters – from rusted cans to glass bottles – that paint a picture of daily life in this former mining community.

Historical Impact on Utah

Jackson’s story captures western Utah’s pioneering era as a vital junction where railroad development and mining activities intersected to shape the region’s growth.

You’ll find that Box Elder County’s early industrial landscape was transformed by the construction of the Lucin Cutoff, which facilitated essential east-west transportation and boosted mining operations throughout the area.

The town’s eventual abandonment mirrors a broader pattern of population shifts in Utah’s western desert, where small railroad and mining settlements often emerged and vanished based on changing industrial needs.

Railroad Development Legacy

When the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads established their crucial junction point in Ogden in 1869, Utah’s transformation into a major rail hub began.

You’ll find that this railroad history reshaped Utah’s community development, with rail lines radiating from Salt Lake City like spokes on a wheel.

Here’s how the railroad network expanded across Utah:

- The Utah Central Railroad connected Ogden to Salt Lake City by January 1870

- The Utah Northern Railroad stretched northward from Brigham City

- The Denver & Rio Grande Western Railway pushed south to Springville

- Local coal lines linked mining communities from Coalville to Park City

The Mormon leadership’s strategic support of railroads as community service tools, rather than profit ventures, helped create an integrated transportation network that revolutionized Utah’s commerce and connectivity.

Mining Industry Influence

The railroads that transformed Utah’s landscape soon intertwined with another powerful force shaping the territory’s development: the mining industry.

In Jackson, you’ll find a perfect example of how mining techniques and transportation merged, as the town primarily served as a railroad siding for mineral freight.

Named after a local prospector, Jackson’s story mirrors many Utah mining settlements. The town’s fortunes followed dramatic economic cycles tied to precious and base metal extraction – silver, copper, lead, and zinc.

These operations attracted a diverse workforce, including immigrant laborers who braved the harsh desert conditions.

However, like many mining ventures, Jackson’s prosperity proved temporary. A devastating dynamite explosion in 1904 accelerated the town’s decline, and when the minerals eventually depleted, the population dispersed, leaving behind another Utah ghost town.

Population Migration Patterns

Population shifts in Utah’s ghost towns often reflected broader Western patterns of boom-and-bust cycles, with Jackson serving as a prime example. This tiny settlement, which peaked at just 45 residents, saw rapid migration trends following the devastating 1904 train collision explosion.

The town’s dramatic depopulation unfolded in these distinct stages:

- Immediate exodus of survivors after the half-mile-radius explosion

- Working-age residents departing for economic opportunities in larger towns

- Young families relocating to emerging urban centers with better safety

- Final abandonment as railroad importance declined

You’ll find that Jackson’s story mirrors many Utah ghost towns, where residents fled after disasters or economic downturns.

The shift from rail-dependent to automobile-based transport further accelerated this rural exodus, permanently altering settlement patterns across the state.

Preserving Jackson’s Legacy

Preserving Jackson’s legacy relies heavily on meticulous archaeological work, as few physical structures remain at this Utah ghost town site.

You’ll find that artifact conservation efforts by the BLM and Utah State Historic Preservation Office have revealed fragments of glass, ceramics, and wood that tell untold stories of past residents.

Volunteer involvement from multiple states has been essential in this painstaking process, especially during the 2020-2021 fieldwork seasons.

The site faces ongoing challenges from desert weathering and illegal metal detecting, but you’re witnessing a coordinated effort to protect these historical resources.

Through partnerships between government entities, archaeologists, and community members, Jackson’s artifacts are being systematically documented and preserved, ensuring this railroad town’s history won’t be lost to time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Native American Settlements in the Jackson Area Before?

You’ll find that Ute tribes maintained seasonal settlements in this area, leaving behind significant Native American cultural impact through their hunting grounds and gathering sites along local waterways.

What Was the Average Temperature and Rainfall in Jackson During Its Operation?

You’d have faced scorching summers reaching 90°F and frigid winters dropping to 20°F, with climate patterns bringing 10-14 inches of annual rainfall, mostly during winter and spring’s seasonal variations.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Pass Through Jackson?

You won’t find any records of famous visitors passing through Jackson. The town’s brief existence as a minor railroad siding and its destruction in 1904’s historical events left little documentation of notable travelers.

What Happened to the Residents Who Survived the 1904 Explosion?

Among 107 widows and 268 fatherless children, you’ll find survivor stories of resilience as families received minimal $500 compensation and worked together on community rebuilding, though many struggled with trauma and poverty.

Were There Any Other Businesses Besides Mining and Railroad Operations?

You’ll find evidence of agricultural practices and local commerce through general stores, trading posts, grocery outlets, and primitive service businesses like chair rentals and barbecue areas serving Jackson’s non-mining residents.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jackson

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AoiIha-3iNo

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Jackson

- https://expeditionutah.com/ghosttowns/

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Utah_Ghost_Towns

- https://utahrails.net/utahrails/us-rr-1870-1881.php

- https://utahrails.net/utahrails/un-rr-1871-1878.php

- https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/r/RAILROADS.shtml

- https://community.utah.gov/utahs-expanding-railroads-and-salt-lakes-west-side/

- http://www.utahweather.org/2015/02/climate-of-utah.html