Junction City emerged in South Dakota’s Black Hills during the 1880 mining boom, driven by prospectors seeking gold after Custer’s 1874 expedition. You’ll find its ruins scattered near the failed Grand Junction Mine, which operated for just three years before economic collapse in 1883. The site features weathered foundations and abandoned mining infrastructure, revealing the harsh realities of boom-bust cycles in Western mining towns. The untold stories of its swift rise and fall await in the crumbling remnants.

Key Takeaways

- Junction City was a Black Hills mining boomtown that experienced rapid economic decline between 1881-1883 due to falling commodity prices.

- The Grand Junction Mine’s abandoned infrastructure, including shaft ruins and mill remnants, stands as evidence of the town’s mining legacy.

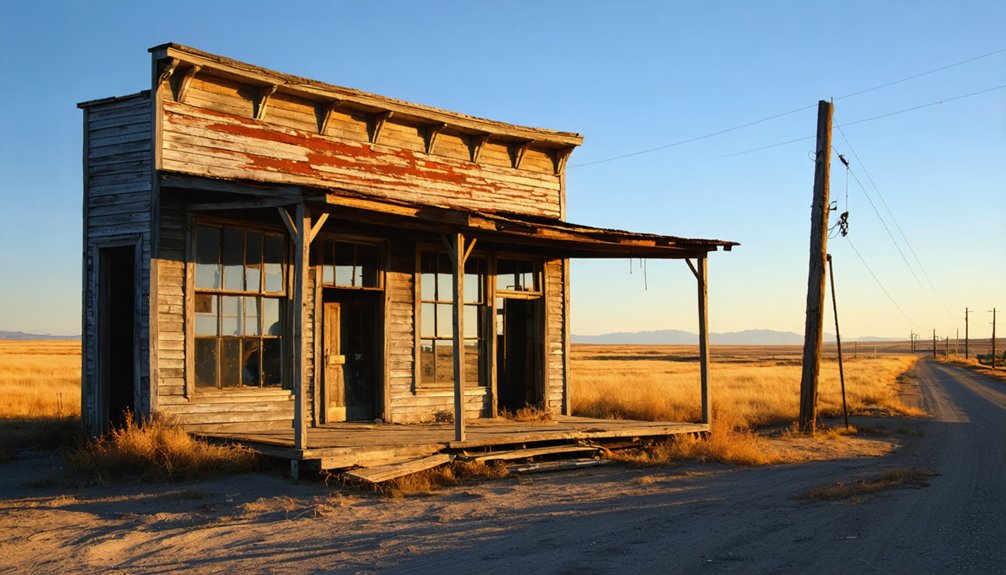

- The ghost town features weathered foundations and crumbling ruins scattered across the landscape, telling stories of its mining past.

- Junction City’s collapse exemplifies the boom-and-bust cycle common to Western mining towns during the Black Hills gold rush era.

- The site faced economic challenges from restricted credit access and single-industry dependence, leading to its ultimate abandonment.

The Black Hills Mining Fever

While the discovery of gold in the Black Hills sparked intense mining speculation throughout the 1890s, the period’s most dramatic activity centered around bustling outposts like Ragged Top, Balmoral, and Maitland.

You’d have witnessed an explosion of speculative mining ventures as newspaper advertisements lured countless prospectors with exaggerated claims of untold riches. Initial gold production reached $1.5 million during the peak year of 1876, driving even more miners to the region. The rush brought both opportunity and lawlessness issues, with over one hundred murders reported in the first year alone.

Despite the chaos, miners established their own unwritten code protecting claims and property rights through informal miners’ courts. The legendary Homestake Mine would go on to produce over 40 million ounces of gold until its closure in 2001.

Amid the lawless frontier, vigilante justice prevailed as miners created makeshift courts to settle territorial disputes and protect their stakes.

As Central City’s prominence waned by 1899, operations consolidated around Deadwood and Lead City. The fever pitch of activity reshaped the region’s landscape, though many speculative ventures ultimately failed to deliver on their golden promises.

Gold Discovery and Town Formation

If you’d been among the first prospectors in 1874, you’d have found placer gold glinting in French Creek’s sediments during Lt. Col. Custer’s military expedition east of present-day Custer, South Dakota.

You’d have witnessed mining camps springing up quickly along creek sites as prospectors defied treaty restrictions on Sioux land to stake their claims.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had guaranteed this territory to the Sioux tribes, making the prospectors’ presence illegal.

The initial discoveries weren’t particularly rich, which drove you and fellow miners to push northward in search of more substantial deposits, leading to the eventual Homestake strike near Lead in 1876. The Homestake Mine operation went on to generate an astounding 10% of global gold production over its 125-year lifespan.

Initial Mining Claims

Prospectors’ pickaxes first struck gold in the Black Hills region surrounding Junction City between 1880 and 1902, targeting rich deposits within chert-silicate units and ferruginous chert beds.

The high concentration of active mining claims today in Pennington County reflects the area’s enduring mineral wealth. Claim staking activities quickly intensified, with miners filing both placer claims for streambed gold and hard-rock claims for lode veins in the bedrock. Deeds like Mining Deed #10939 documented substantial $1,500 investments in multiple claims including the Alliance Extension and Bessie Lodes. You’ll find nearly 49,000 recorded claims in South Dakota, many concentrated in Pennington and Lawrence counties.

Legal battles erupted as mining claims overlapped with growing townsites built on mineralized lands. Companies like Homestake negotiated surface rights with residents, establishing agreements for compensation and advance notice before mining.

These compromises proved essential for balancing mining operations with town development. The federal mining laws strictly governed claim management, while access to water rights and timber resources often sparked additional disputes.

Rush for Gold Begins

When George Armstrong Custer’s 1874 expedition confirmed gold in French Creek near present-day Custer, South Dakota, it sparked one of America’s last great gold rushes.

Word spread quickly, and despite the land being protected Sioux territory under the Fort Laramie Treaty, thousands of determined prospectors flooded into the Black Hills. The territory had been recognized as Sioux land through the Treaty of Laramie in 1868.

The mining expansion transformed the untamed wilderness into bustling settlements:

- Tent cities emerged along creek beds as prospectors sought their fortune in placer deposits.

- Early arrivals staked claims to “poor man’s diggings” using simple tools and mercury amalgamation.

- Towns like Deadwood, Lead, and Custer sprang up virtually overnight, complete with services and rudimentary infrastructure.

The rush intensified in 1875 when rich deposits were discovered in Deadwood Gulch, drawing even more fortune seekers to the region.

Similar to Junction City, California’s early placer mines, these initial operations laid the groundwork for more extensive mining developments in the area.

Life in a Mining Boomtown

Life in a mining boomtown presented five distinct social strata, from wealthy mine owners to transient laborers seeking their fortunes.

You’d find a clear social hierarchy, with mine operators at the top, followed by skilled workers, merchants, unskilled laborers, and drifters at the bottom. Community identity emerged through saloons, social clubs, and makeshift churches, though these institutions developed slowly amid the chaos of rapid growth.

Boomtown society followed strict class divisions, from wealthy operators to wandering laborers, while saloons and churches slowly knit the community together.

The town’s population surged with young men drawn by labor demands and dreams of striking it rich. The proximity to the Homestake mine at Lead attracted many fortune seekers to the area. The sudden influx of people created severe housing shortages throughout the settlement.

You’d witness a bustling economy of supply stores, lodging houses, and entertainment venues catering to miners’ needs. Living conditions remained rough, with hastily built wooden structures and overcrowded quarters.

Despite the challenges of inadequate sanitation and limited infrastructure, residents forged bonds through shared experiences and mining traditions.

The Grand Junction Mine Operations

The Grand Junction Mine emerged as a significant operation in 1878 when C.C. Crary discovered promising gold and silver deposits on a central hill in what would become Junction City.

Despite initial optimism, you’ll find the mine’s brief history marked by challenging operations and limited success. The relatively shallow shaft depth and basic ore processing facilities managed to extract approximately 7,000 tons of ore during its three-year run.

Here’s what the mine achieved before closing in 1881:

- Processed ore yielding $3.59 in gold per ton

- Generated total revenue of $25,000

- Provided enough initial activity to establish a small mining community

The operation’s struggles with low-grade ore and insufficient returns ultimately led to its closure, though the site’s ruins near Junction Ranger Station continue to tell the story of Black Hills mining ambition.

A Swift Economic Downfall

Despite Junction City’s early promise as a mining settlement, its economic foundation crumbled rapidly between 1881 and 1883.

You’ll find striking parallels between Junction City’s collapse and South Dakota’s historical pattern of rural decline, where economic challenges have repeatedly devastated frontier communities.

Like many small towns that followed, Junction City couldn’t withstand the devastating combination of falling commodity prices and restricted credit access that plagued the region.

The town’s fate mirrored South Dakota’s broader vulnerability to economic shocks – similar to the agricultural depression that began in 1923.

As the community navigates its challenges, residents have taken the initiative to explore Kiddville’s rich history, uncovering the stories of perseverance and resilience that define their identity. These historical insights have fostered a renewed sense of pride, prompting many to share their experiences and contribute to local projects. In doing so, they are not only preserving their heritage but also inspiring future generations to cherish their roots.

When the mine’s production costs outpaced profits, businesses shuttered quickly, and residents fled.

This swift downfall exemplified the boom-bust cycle that you’ll see repeated throughout South Dakota’s rural communities, where single-industry dependence often spelled disaster when market conditions turned unfavorable.

Legacy of a Failed Mining Venture

Mining operations at Grand Junction Mine left an enduring legacy of financial and environmental consequences that you can still observe today.

The venture’s swift collapse highlighted the volatile nature of speculative mining investments in the Black Hills region during the late 1800s.

The economic implications and environmental consequences of the failed mine remain evident through:

- Abandoned infrastructure including shaft ruins and mill remnants that stand as stark reminders of the $25,000 total yield that couldn’t sustain operations.

- Environmental hazards from mining activities that mirror broader contamination issues throughout the Black Hills.

- Physical transformation of Junction City into a ghost town, representing the broader pattern of boom-and-bust mining settlements that dot the region’s landscape.

These lasting impacts serve as a reflection of the risks and challenges faced by frontier mining enterprises.

Exploring the Ruins Today

While Junction City‘s heyday has long passed, visitors today can explore the scattered remnants of this once-bustling mining settlement near the Junction Ranger Station.

You’ll find weathered foundations and crumbling ruins dotting the landscape, silent witnesses to the town’s historical significance as a frontier mining community.

The most notable abandoned structures belong to the Grand Junction Mine, which gave the town its name.

As you walk among these deteriorating remains, you can piece together the layout of what was once a hopeful venture into mineral extraction.

Though time and elements have taken their toll, these ruins serve as tangible connections to the region’s mining heritage.

Despite decades of weathering, the scattered ruins stand as silent storytellers, linking modern visitors to the area’s rich mining past.

The site offers a raw, unfiltered glimpse into the boom-and-bust cycle that characterized many Western mining towns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Dangerous Mine Shafts or Hazards Visitors Should Watch For?

You’ll need to watch for hidden vertical and horizontal mine shafts near the Grand Junction Mine ruins. For mine safety, avoid entering structures and stay alert for unmarked holes and unstable ground.

What Was the Closest Neighboring Town During Junction City’s Operation?

In a time when mountains of gold brought dreamers to every valley, Custer was your nearest neighboring settlement, serving as the major supply hub during Junction City’s short-lived town history.

Did Any Notable Historical Figures Ever Visit Junction City?

You won’t find any famous visitors in the historical record. The town’s limited historical significance and brief operational period from 1878-1881 didn’t attract any notable figures to this mining settlement.

Were There Any Documented Crimes or Lawlessness During the Town’s Existence?

Primary papers present peculiarly peaceful patterns – you won’t find any crime reports or law enforcement records from Junction City’s brief existence. Historical sources and surviving documents show no documented criminal activity.

What Indigenous Tribes Originally Inhabited the Area Before Mining Began?

You’ll find the Lakota, Dakota, and Yanktonai tribes were the primary Native tribes in this area, with their rich cultural heritage centered on hunting bison and maintaining complex trade networks along the Missouri River.

References

- https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-2-2/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins/vol-02-no-2-some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0WNYsFLSLA

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/sd/junctioncity.html

- https://adventure.com/usa-americas-forgotten-ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_South_Dakota

- https://b1027.com/south-dakota-has-an-abundance-of-ghost-towns/

- https://explore.digitalsd.org/digital/collection/WPGhosttown/id/3951/

- https://freepages.history.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/usa/sd.htm

- https://history.sd.gov/museum/docs/Mining.pdf

- https://www.sdpb.org/rural-life-and-history/2023-08-28/the-boom-and-bust-of-central-city