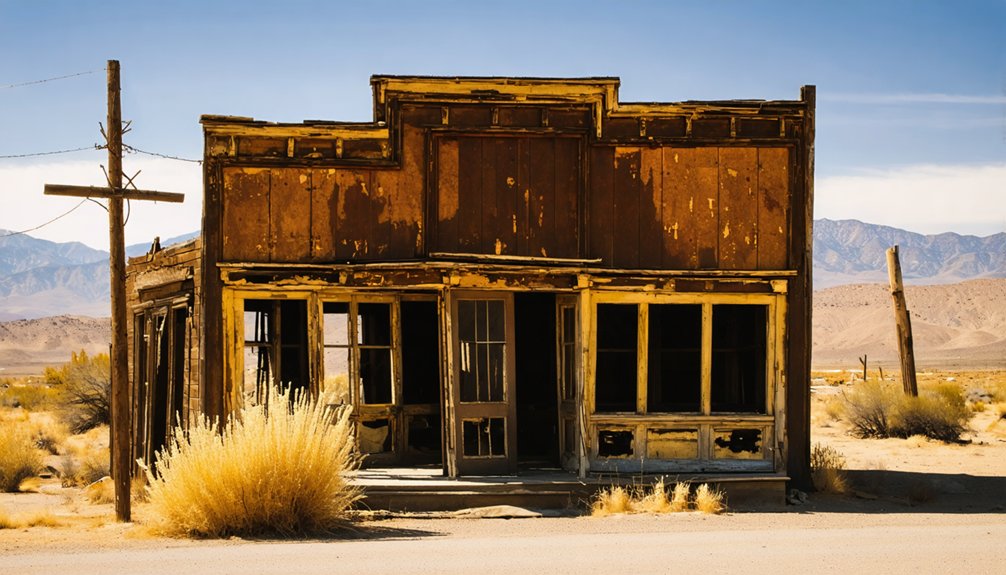

You’ll find Keeler clinging to the eastern shore of what was once Owens Lake, a ghost of its 1870s silver boom heyday. Originally Cerro Gordo Landing, this former shipping hub saw mule trains and steamships before the Carson & Colorado Railroad arrived in 1883. When Los Angeles diverted the Owens River in 1913, Keeler’s population plummeted from 5,000 to about 50 today. The cracked alkali flats tell a cautionary tale of boom-to-dust transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Once a bustling silver mining town with 5,000 residents, Keeler is now a ghost town with fewer than 50 people.

- Founded in the 1870s as a shipping point for silver, Keeler’s decline began when Los Angeles acquired water rights in early 1900s.

- The Owens Lake dried up by 1926, transforming the former port town into alkali flats plagued by toxic dust storms.

- Historical significance includes the Carson & Colorado Railroad arrival in 1883 and the town’s marble contributions to California architecture.

- Recent restoration efforts focus on dust control, with nearby Cerro Gordo serving as a model for ghost town preservation.

The Silver Boom: Keeler’s Rise as a Mining Transport Hub

While prospectors sought fortune in California’s gold fields, the lesser-known settlement of Keeler carved its own niche in mining history along the eastern shores of Owens Lake.

Originally dubbed Cerro Gordo Landing, this hardscrabble outpost emerged in the 1870s when Mortimer Belshaw, dissatisfied with existing arrangements, established a strategic shipping point for his silver interests.

Ambition built Cerro Gordo Landing—Belshaw’s calculated response to logistics challenges in the unforgiving Inyo wilderness.

You’d have witnessed mule trains descending the steep Inyo Mountains via the Yellow Road, hauling eighteen tons of silver-lead bullion daily at peak production. The ore harvested from these operations was valued at $17 million.

The mining operations transformed Keeler from a simple landing into a bustling hub when the Carson & Colorado Railroad arrived in 1883.

In 1881, the growing settlement was officially renamed after Capt. Julius M. Keeler, marking its transition from a temporary outpost to an established town.

The economic impact was immediate—smelters, tramways, and shipping facilities created jobs while connecting this remote outpost to markets in Los Angeles.

From Steamships to Railroads: Transportation Evolution on Owens Lake

When fire claimed the *Bessie Brady* in 1882, the writing was on the wall.

The limitations of water-to-wagon transport fueled hunger for something faster and more reliable—iron horses that would soon render obsolete the brief but essential era of Owens Lake steamships. This transition was accelerated when the railroad arrived in 1879, providing a more efficient alternative to the struggling steamboat operations. The decade-long steamboating era that began in 1872 represented a unique chapter in eastern California’s maritime history.

The Fateful Drought: How Los Angeles Water Diversion Changed Keeler

As the ink dried on Los Angeles’ water rights acquisitions in the early 1900s, few residents of bustling Keeler could have predicted their town’s impending doom.

When Mulholland’s aqueduct began siphoning Owens River in 1913, you’d have noticed the lake receding gradually, then faster.

“They’re stealin’ our lifeblood,” old-timers would lament at Keeler’s general store.

By 1926, where steamships once docked, you’d find only cracked alkali flats stretching toward the horizon.

The ecological justice implications weren’t considered then—the destruction of migratory bird habitat, choking dust storms, and the economic devastation as your neighbors packed up and fled.

A town of thousands dwindled to fewer than a hundred souls.

Your water rights vanished in the California dust, sacrificed for a distant city’s growth.

What was once a prosperous shipping port with a peak population of 5,000 residents in the 1870s now stands as a haunting reminder of environmental mismanagement.

The town once functioned as an essential stop for steamer ships transporting silver to Los Angeles before the environmental changes devastated the area.

Architectural Legacy: Keeler Marble in California’s Iconic Buildings

While Keeler’s water rights vanished, something far more enduring emerged from the town’s surroundings—pure white marble that would become part of California’s architectural identity.

You’ll find Keeler marble’s finest showcase at San Francisco’s Mills Building, where it clads the first two stories in pristine white stone. Quarried from the rugged Inyo Mountains and hauled by rail to bustling cities, this fine-grained marble embodied the late 19th century’s architectural ambitions.

Its durability has withstood earthquakes and time itself.

The marble’s architectural significance extends beyond Mills—it appears in Beaux-Arts and Richardson-Romanesque buildings throughout California. Like Ray Kappe’s modern Keeler House design, the material demonstrates California’s enduring architectural innovation. The integration of natural materials reflects Kappe’s philosophy of harmonizing structures with their surroundings.

Though the quarry’s operations were brief, the stone’s legacy endures in these structures. When you stand before these buildings, you’re witnessing Keeler’s most permanent contribution to the Western landscape.

Ghost Town Tourism: Exploring Keeler’s Historical Remnants Today

Today’s ghost town explorers find Keeler a haunting symbol to boom-and-bust cycles that shaped the American West.

You’ll need a high-clearance vehicle to navigate the 8-mile gravel road from State Route 136, especially during winter months when conditions worsen.

While Keeler itself offers limited structured tourism, nearby Cerro Gordo ghost town, perched at 8,500 feet in the Inyo Mountains, provides guided tours for $10 per adult.

The American Hotel (1871), 1904 Bunkhouse, and Belshaw House (1868) stand as representations of mining-era prosperity.

Visitors can see the historic site where the Hotel Keeler once stood before it was destroyed by fire on March 19, 1928.

Ghost town preservation efforts require visitors obtain caretaker authorization before entering structures.

Tourism challenges include difficult access roads with hairpin turns and steep drops.

Visitors are encouraged to acknowledge that this area is the traditional homeland of Paiute peoples who have inhabited the Eastern Sierra region for generations.

Environmental Impact: Dust Storms and the Aftermath of a Dried Lake

When you drive into Keeler today, you’re met with the stark reality of toxic dust storms that have plagued the town since Owens Lake dried up in 1926.

The lakebed’s arsenic-laced dust, now America’s largest source of PM10 pollution, has forced many locals to abandon their homes while those who stayed face serious respiratory illnesses.

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power now spends upwards of $25 million annually on massive restoration efforts, including shallow flooding and vegetation projects, to tame the environmental disaster they created nearly a century ago.

Toxic Dust Hazards

How did a once-thriving lakeside community become besieged by toxic clouds? When Los Angeles diverted Owens River in 1913, they sentenced Keeler to death by dust.

The exposed lakebed cracked open like an old wound, releasing America’s worst PM10 particulate pollution.

You’ll see it coming—massive walls of choking dust carrying arsenic and mineral salts straight into your lungs. Locals call these “Keeler episodes” when visibility drops to near zero and breathing becomes hazardous work.

Toxic exposure has driven most folks away, with respiratory health issues plaguing those stubborn enough to stay.

“When that dust rolls in, you can taste it,” says one longtime resident. “Some days, you just can’t go outside.”

The town’s population has dwindled from 5,000 to barely 50 souls today.

Restoration Efforts Underway

Despite decades of environmental devastation, restoration efforts have begun tackling Keeler’s toxic dust crisis head-on.

Just up the road, Cerro Gordo’s successful restoration model offers hope, with Brent Underwood’s team balancing historic preservation against the relentless dust storms that plague the region.

You’ll notice sophisticated mitigation techniques now employed throughout the area—managed vegetation cover and soil stabilization on the lakebed’s barren flats.

Local crews have adapted restoration techniques using materials that withstand Owens Valley’s punishing winds. The rebuilt American Hotel stands as proof of their determination.

Tourism development plans proceed cautiously, with stakeholders acknowledging the delicate balance between welcoming visitors and respecting the land.

“We’re fighting the lake’s ghost,” one restoration volunteer told me, “but folks deserve to see this slice of California history without choking on its past.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to Keeler’s Original Residents After the Mining Collapse?

Migrants moved mournfully away when the mining collapse eliminated jobs. You’d have found original residents relocating to other boomtowns or cities where they’d secure steady work, leaving Keeler’s dust storms behind.

Were Any Movies or TV Shows Filmed in Keeler?

Y’all bet they were! Westerns like “Three Godfathers” and “I Died a Thousand Times” used your ghost town’s authentic grit. The film history runs deep—Gene Autry even shot his TV show there.

How Safe Is Keeler for Visitors Today?

Desolate dangers demand diligence. You’re reasonably safe exploring this ghost town if you’re prepared. Bring water, watch for structural hazards, mind the rough roads, and don’t wander into abandoned mines or decrepit buildings.

Are There Any Active Preservation Societies for Keeler?

Yes, you’ll find the Early Era Preservation Society actively working to restore Keeler’s historical significance. Railroad enthusiasts preserve the Carson and Colorado line, while collaborating with Cerro Gordo’s foundation on regional preservation efforts.

What’s the Closest Modern Town to Keeler With Amenities?

You’ll find modern amenities in Lone Pine, just 15 miles northwest via SR-136 and US-395. It’s your gateway to civilization, offering everything from groceries to medical care that Keeler’s ghost town status can’t provide.

References

- http://www.weirdca.com/location.php?location=370

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJxFNnjXaCs

- https://tisqui.github.io/2017/10/01/keeler.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDCKQTrySlM

- https://francescascalpi.com/keeler

- https://lonepinechamber.org/history/ghost-towns-of-the-lone-pine-area/

- https://desertgazette.com/blog/keeler-california/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keeler

- http://www.eugenecarsey.com/ghosttowns/keeler/keeler.html

- https://beyond.nvexpeditions.com/california/inyo/keeler.php