You’ll find Kendall’s fascinating stone ruins in Montana’s North Moccasin Mountains, where a revolutionary cyanide gold processing method transformed a modest mining camp into a booming town of 1,500 residents by 1901. The town featured modern amenities, stone buildings, and earned $800 daily in gold production during its peak. Though fires and economic shifts led to its abandonment by 1920, Kendall’s well-preserved remains offer a compelling window into Montana’s golden era.

Key Takeaways

- Kendall was a thriving gold mining town in Montana’s North Moccasin Mountains that peaked with 1,500 residents in the early 1900s.

- The town’s success stemmed from innovative cyanide processing technology, which extracted gold from low-grade ore with 90% efficiency.

- Notable stone buildings included the Jones Opera House, Shaules Hotel, and multiple businesses, showcasing the town’s architectural heritage.

- Downtown fires between 1908-1910, declining ore quality, and nearby railroad development led to Kendall’s eventual abandonment by 1920.

- Today, Kendall’s stone ruins and foundations remain as a preserved ghost town site, attracting visitors interested in Montana’s mining history.

The Birth of a Gold Mining Boomtown

While early prospectors discovered gold placers in the North Moccasin Mountains during the 1880s, Kendall’s true mining boom didn’t begin until the dawn of the 20th century.

Initial placer mining struggled due to water scarcity, and early pyrite deposits proved disappointing, but everything changed with the implementation of innovative cyanide processing in 1900. Large gold nuggets in gulches were discovered during these early mining efforts.

The advent of cyanide processing in 1900 revolutionized Kendall’s mining operations, overcoming earlier challenges of water shortages and poor pyrite yields.

Long workdays and labor were required as miners searched for valuable deposits, similar to other Montana mining operations of the era.

You’ll find that Kendall Mining Company‘s success transformed this modest mining site into Montana’s richest gold town.

The economic impact was immediate – daily earnings of $800 and $2.5 million in bullion over five years sparked rapid development.

By 1901, you’d have seen a thriving community of 1,500 residents, complete with modern amenities like banks, hotels, churches, and an opera house.

Two daily stagecoaches connected you to Lewistown, establishing Kendall as more than just another transient mining camp.

Harry Kendall’s Revolutionary Cyanide Process

The revolutionary changes in Kendall’s mining fortunes can be traced directly to Harry Kendall’s introduction of a small cyanide gold recovery plant in 1899. This cyanide innovation transformed the extraction of microscopic gold particles from low-grade oxide ore, achieving an impressive 90% recovery rate – far surpassing traditional methods.

You’ll find that this mining technology breakthrough quickly sparked the region’s economic boom. The Kendall Mining Company pulled in $800 daily, amassing $2.5 million in bullion during its first five years. The town grew rapidly to become home to Presbyterian worshippers who built their own church at the base of a hill.

Direct cyanidation of crushed ore proved particularly valuable in Montana’s water-scarce environment, eliminating the need for water-intensive placer mining. The process’s success supported a thriving community of 1,500 residents and brought modern amenities like electric power to this frontier mining town. The town’s large underground mines continued producing gold into the 1990s, yielding an additional 350,000 ounces of the precious metal.

Life in a Thriving Mountain Community

Following Harry Kendall’s mining breakthrough in 1899, Kendall rapidly evolved from a small mining camp into a bustling mountain community of 1,500 residents.

You’d find remarkable cultural diversity in the town’s social dynamics, from Methodist and Presbyterian congregations to Catholic services, all sharing public spaces before permanent churches emerged.

Daily life revolved around the town’s impressive stone buildings, including the Jones Opera House, where you could enjoy entertainment after a day’s work. The local stone quarry supplied all the building materials that gave the town its distinctive character.

You’d have your choice of five saloons, three stores, and various services from tailoring to banking. The Kendall Chronicle kept you informed of local happenings, while the two-story schoolhouse and hospital provided essential community services.

Multiple daily stagecoaches guaranteed you weren’t isolated, despite the town’s mountain setting. The Barnes-King mine was the town’s economic backbone until its closure in 1920 marked the beginning of Kendall’s decline.

Architecture and Infrastructure Development

You’ll find Kendall’s architectural legacy in its locally quarried stone buildings and wooden-framed structures, which housed everything from the Jones Opera House to the 50-ton cyanide mill.

The town’s purposeful layout on the Shaules homestead efficiently integrated residential, commercial, and industrial needs, including two stagecoach lines connecting to Lewistown.

While many buildings haven’t survived, the remaining stone walls and foundations tell the story of a well-planned mining community that boasted modern amenities like electrical power and specialized industrial facilities.

Historical Building Materials

Stone masonry and timber construction defined Kendall’s architectural landscape during its heyday, with local granite and quarried stone serving as the primary building materials for prominent structures.

You’ll find evidence of stone durability in the remaining thick-walled ruins, including the Presbyterian Church, T.R. Matlock Store, and the bank vault in the J.R. Cook Building. The Jones Opera House showcased impressive stone-faced facades that combined strength with visual appeal.

When fires struck in 1908 and 1911, residents engaged in timber salvaging, removing lumber from buildings they couldn’t relocate. The town’s electrical power availability enabled the use of modern construction equipment during building projects.

Many structures featured stone foundations supporting multi-story designs, while others incorporated both materials strategically. The most enduring remnants today are those built with substantial stone walls, proof of the material’s fire-resistant properties.

Community Planning Layout

While many mining towns grew haphazardly, Kendall’s layout reflected careful adaptation to the North Moccasin Mountains‘ natural terrain.

You’ll find the mining operations strategically positioned around the main gold claims, with the cyanide mill placed near ore sources for efficient processing. The town’s residential clustering kept homes and businesses close to the central mining infrastructure, making daily operations more convenient for workers and merchants. Located about twelve miles from Lewistown on Highway 87, the site required thoughtful planning to maximize accessibility. The first cyanide mill in the district revolutionized local ore processing capabilities.

Communal spaces formed the heart of social life, with the Presbyterian Church, bandstand, and Jones Opera House serving as cultural anchors.

Though you won’t find evidence of a formal grid system, the town’s pathways developed organically between these gathering spots. The cemetery’s thoughtful placement near Hilger maintained a respectful distance from daily activities while remaining accessible to residents.

Modern Structural Remnants

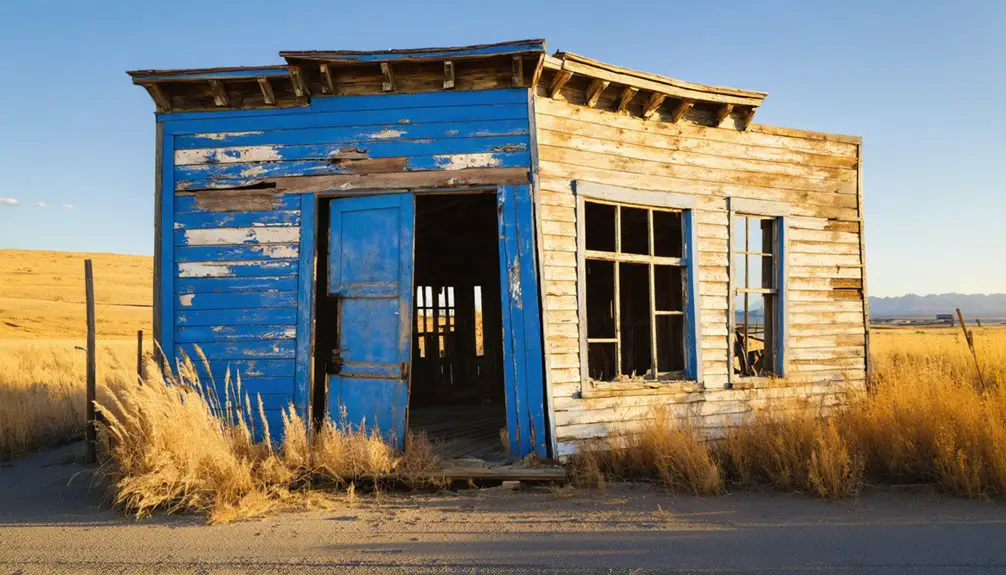

Despite the passage of time, Kendall’s most resilient architectural features remain visible through three prominent stone ruins: the T.R. Matlock Store, J.R. Cook Building bank vault, and First Presbyterian Church walls.

These thick-walled structures, built from local quarried rock, stand as evidence to the ghost town architecture that once defined this mining community. Today, the site represents Montana’s mining heritage, drawing visitors interested in exploring the state’s rich historical background.

You’ll find the bandstand as one of the few above-ground structures still intact, while the Presbyterian Church ruins showcase remnants of its two-story Scotch-influenced design.

Historical preservation efforts have added interpretive signage and visitor amenities like picnic tables, while maintaining the site’s authenticity.

The granite boulder with drill holes serves as a unique industrial relic, connecting you to the town’s mining heritage and skilled labor culture.

The Golden Years of Prosperity

You’ll find that Kendall’s golden years were marked by impressive daily gold production averaging $800, with the Kendall Mining Company extracting $2.5 million in bullion over just five years.

The town’s prosperity supported a rich community life, complete with two hotels, five saloons, an opera house, and modern amenities like electricity from the Kendall Power Plant.

Your journey through 1900s Kendall would have revealed a bustling population of 1,500 residents enjoying advanced infrastructure rarely seen in remote mining towns, including hot water heating, cultural venues, and twice-daily stagecoach service to Lewistown.

Mining Wealth Drives Growth

The introduction of Harry Kendall’s cyanide plant in 1899 transformed Kendall into a thriving mining boomtown, releasing the region’s dormant wealth potential. This revolutionary mining technology allowed profitable extraction from low-grade ore that you’d previously have to ignore, sparking an economic impact that rippled through the North Moccasin Mountains.

You’d have witnessed these signs of prosperity in Kendall’s peak years:

- A bustling population of 1,500 residents building their dreams with locally quarried stone.

- Modern infrastructure including a power plant on Warm Spring Creek powering both mines and homes.

- Half a million ounces of gold extracted over two decades, with the Kendall mine alone selling for $1.2 million in 1906.

The Barnes-King Mining Company’s large-scale operations and robust transportation networks cemented Kendall’s position as a formidable mining center.

Community Life Flourishes

Mining wealth swiftly transformed Kendall into a vibrant community where you’d find all the amenities of a modern early 1900s town.

You could catch the latest shows at Jones Opera House, read local news in the Kendall Chronicle, or attend services at one of the churches. The Shaules Hotel offered luxurious accommodations with hot water, heating, and electricity – rarities for a remote mining town.

Community events and social gatherings thrived across the town’s establishments. You’d find miners celebrating their fortunes at five different saloons, while others dined at local restaurants.

The town’s infrastructure supported daily life with two livery stables, multiple stores, and a school for families. Despite devastating fires in 1908 and 1911, the resilient community rebuilt, determined to maintain their flourishing way of life.

From Bustling Town to Silent Ruins

During its heyday in the early 1900s, Kendall flourished as Montana’s richest gold mining town, transforming from an untamed mountainside into a bustling community of 1,500 residents.

The social dynamics shifted dramatically after 1912 when ore quality diminished, causing economic shifts that rippled through the community.

You can imagine the town’s gradual descent into silence through these pivotal changes:

- Downtown fires between 1908-1910 devastated key business structures.

- The founding of nearby Hilger in 1911 drew residents away with its railroad access.

- Major mines began closing in 1920, leaving only scattered placer operations into the 1930s.

Today, you’ll find Montana’s best-preserved ghost town nestled in the North Moccasin Mountains, where century-old stone ruins stand as evidence of Kendall’s golden age.

Boy Scouts and Historical Preservation

Young Boy Scouts have played an essential role in preserving Kendall’s historic legacy through organized conservation and restoration projects.

You’ll find evidence of Scouts’ contributions throughout the ghost town, from restored split-rail fencing to carefully maintained hiking trails and interpretive kiosks that tell the story of this once-bustling Montana community.

Through the Historic Trails Award program, local troops have partnered with historical societies to mark significant sites, conduct preservation work, and promote awareness of Kendall’s rich heritage.

Their preservation projects include building accessible walkways, controlling stream erosion, and maintaining native plant gardens around historic structures.

These hands-on efforts not only protect Kendall’s cultural resources but also connect young people with the authentic stories of Montana’s mining era while teaching them valuable conservation skills.

Exploring the North Moccasin Mountains

Rising to an elevation of 5,384 feet, the North Moccasin Mountains stand as a distinctive geological landmark northwest of Hilger in Fergus County, Montana.

The mountain geology features Paleozoic sedimentary rocks and notable intrusive formations, creating a complex landscape that’s shaped by historical gold mining operations.

When you explore these mountains, you’ll discover:

- Karst breccias that once yielded rich gold deposits in the Kendall mining district

- A network of accessible roads winding through both North and South ranges

- A diverse wildlife habitat supporting native species adapted to the continental mountain ecosystem

You can drive through the range year-round via Montana Highway 81, though weather conditions vary considerably with elevation.

The mountains’ unique geological composition, from limestone formations to mineral intrusions, tells the story of Montana’s rich mining heritage.

Planning Your Visit to Kendall Ghost Town

Located in the heart of the North Moccasin Mountains, Kendall Ghost Town offers visitors a fascinating glimpse into Montana’s gold mining era.

You’ll find the site easily accessible via North Kendall Road from Hilger, with clear historical markers guiding your way.

For the best ghost town photography opportunities, plan your visit between spring and fall when you can capture the stone ruins against stunning mountain backdrops and seasonal foliage.

You’ll discover remnants of the town’s notable structures, including the preserved bandstand, Presbyterian Church ruins, and the thick-walled bank vault.

Make the most of your expedition by combining your Kendall visit with trips to nearby ghost towns Maiden and Gilt Edge.

Don’t miss the interpretive panels that detail the site’s rich mining history while you explore the century-old foundations and walls.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Reported Paranormal Activities or Ghost Sightings in Kendall?

You won’t find documented ghost sightings or paranormal encounters in Kendall’s historical records. The area’s focus remains on its mining heritage and outdoor recreation through Boy Scout activities.

What Happened to the Gold Mining Equipment After the Town Was Abandoned?

You won’t find much original gold mining equipment there today – it was mostly salvaged, sold to scrap dealers, or removed by the 1940s. Modern operations brought their own gear later.

Can Visitors Collect Mineral Specimens or Artifacts From the Site?

You can’t collect mineral specimens or artifacts from Kendall since it’s protected Boy Scout property. The site’s preservation requires leaving all historical items untouched for future generations to study and appreciate.

Were There Any Major Crimes or Shootouts During Kendall’s Peak Years?

You won’t find any documented major crimes or shootouts in Kendall’s crime history. The town maintained a peaceful atmosphere during its peak years, focusing on mining success rather than violence.

Does Anyone Still Own Private Property Within the Original Townsite Boundaries?

Like a closed chapter in history, you won’t find private property owners within the original townsite boundaries today – it’s all consolidated under K Bar M Scout Ranch’s institutional ownership.

References

- https://www.raisedinthewest.com/archives/kendall-ghost-town-in-the-north-moccasin-mountains

- https://www.mtghosttowns.com/kendall

- https://scoutingmontana.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/KM-History.pdf

- https://centralmontana.com/blog/visiting-the-ghost-town-of-kendall-in-central-montana/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/kendall/

- https://dp.la/exhibitions/industries-settled-montana/mining

- https://westernmininghistory.com/mine-detail/10269407/

- https://www.montanaliving.com/blogs/destinations/explore-montana-ghost-towns

- https://discoveringmontana.com/ghost-town/kendall/

- http://montanaranchandrecreation.blogspot.com/2012/06/montana-history-detour-kendall-mt.html