Kingston, California was a thriving riverside settlement established in 1854 along the Kings River during the Gold Rush. You’ll discover it served as a crucial transportation hub with ferry service, Butterfield Overland Mail route access, and commercial significance between Millerton and Visalia. Today, only scattered foundations and a historical marker remain after natural disasters devastated the area. The site preserves complex stories of Native American relations and 19th-century frontier commerce.

Key Takeaways

- Kingston was established around 1854 along Kings River during the California Gold Rush as a ferry crossing point.

- Once a thriving commercial hub between Millerton and Visalia, Kingston served as a station on the Butterfield Overland Mail route.

- The settlement had complex relations with Native Americans, including a nearby rancheria housing approximately 300 indigenous residents.

- Kingston’s decline followed natural disasters that devastated the area, redirecting traffic after the Kingston Bridge collapse.

- Today, only scattered foundations, trees, and a historical marker remain at the site along the Kings River.

The Birth of a Riverside Settlement (1854-1859)

As the California Gold Rush transformed the state’s landscape in the mid-19th century, Kingston emerged along the Kings River around 1854 as a strategic settlement serving both practical and economic needs.

Settler motivations centered on establishing a significant river crossing point that would connect communities and facilitate travel throughout the region.

Whitmore, a key founder married to a Yokut woman, established an important ferry service that became Kingston’s economic backbone. The settlement quickly grew around his homestead, coinciding with Fresno County’s creation from Tulare County in 1856.

River transportation dominated the town’s early economy, positioning Kingston as a crucial hub for the Butterfield Overland Mail route by 1858. Kingston also gained prominence as it was situated along the historic El Camino Viejo route connecting San Francisco Bay to Los Angeles. James Edward Denny became the settlement’s first postmaster in 1859.

This riverside community exemplified the peaceful coexistence between settlers and the local Yokut population during California’s rapid expansion.

Racial Tensions and the Founder’s Tragic End

While Kingston’s early years showcased a harmonious riverside settlement, violent racial tensions soon shattered this fragile peace.

In January 1859, town founder Whitmore was murdered by Dr. Workman and his anti-Indian posse during widespread conflicts with Native Americans in the San Joaquin Valley.

Whitmore’s marriage to a Yokut woman and his opposition to racial violence had made him a target. His murder exemplified the deadly consequences faced by those who allied with Indigenous peoples during this era of hostility. This pattern of racial exclusion mirrors how sundown towns operated throughout California’s history.

The incident occurred alongside a broader campaign of racial violence that claimed approximately 50 Native American lives in a single roundup. Many of these exclusionary practices were enforced through police intimidation and violence similar to those in documented sundown towns.

Despite this dark chapter in Kingston’s historical legacy, the area eventually developed relatively peaceful coexistence with the nearby Native American rancheria, where about 300 people maintained their cultural practices.

Native American Relations and the Kingston Rancheria

Despite the violent racial tensions that claimed Kingston’s founder, a notable Native American settlement emerged just west of the town. This Kingston Rancheria housed approximately 300 indigenous residents who maintained their cultural traditions despite the surrounding hostility.

While California’s Gold Rush era devastated Native populations through systematic genocide, killing an estimated 100,000 indigenous people in just two years, the rancheria represented remarkable cultural resilience.

The community regularly practiced traditional ceremonies, used sweat lodges, and accessed the southwest river for cultural activities. This peaceful coexistence contrasted sharply with the broader regional violence, where vigilante groups routinely targeted Native Americans for killing, enslavement, and sexual violence. The rancheria established itself amid the decimation of California’s native population density, which had been the highest north of Mexico before European contact.

The rancheria stands as evidence of indigenous survival amid California’s colonial violence, where Native peoples were typically viewed as obstacles to economic expansion rather than sovereign communities. Similar to the indigenous resilience movements seen across Southern California, the Kingston Rancheria’s inhabitants fought to preserve their cultural identity despite widespread oppression.

The Boom Years: Commerce Along the Kings River

Strategically positioned along major trading corridors, Kingston flourished as an essential commercial hub during its boom years. The town served as the only stopping point between Millerton and Visalia, and between Visalia and Los Banos, making it crucial to regional trade networks.

Its location along El Camino Viejo and the Kings River connected northern and southern California commerce through ferry operations.

O.H. Bliss exemplified Kingston’s commercial significance by simultaneously functioning as ferry operator, Wells Fargo agent, notary, postmaster, and livery stable owner.

The town’s economic foundation rested on the agricultural impact of surrounding fertile farmland and the steady flow of goods from Stockton. John Poole’s Trading Post also served the area’s commercial needs before Kingston fully developed its own infrastructure.

The river’s ability to support fertile lands helped sustain Kingston’s prosperity as agricultural production expanded throughout the region.

Ferry tolls—25 cents for pedestrians and 75 cents for horse and buggy—generated reliable revenue until the Kingston Bridge collapse in the 1880s redirected traffic to Laton.

The Ghost Town Today: Remnants of a Forgotten Past

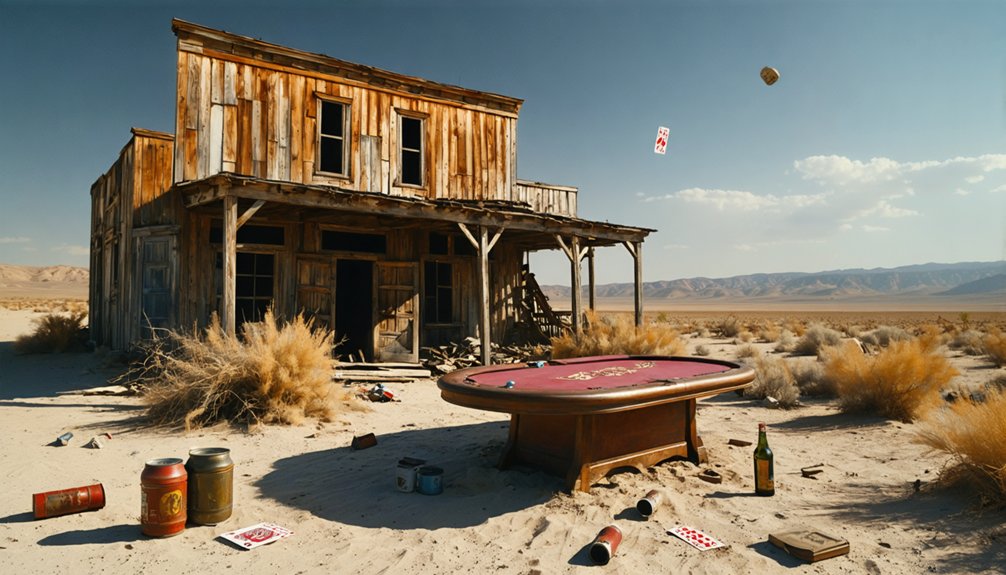

Shadows of California’s past linger at the once-thriving settlement of Kingston, now reduced to minimal physical remnants along the Kings River.

You’ll find only scattered cement foundations and trees where this bustling riverfront town once stood. A historical marker commemorates Kingston’s brief existence and tragic decline, particularly highlighting the connection to Native American communities and the pivotal events surrounding Alfred Whitmore’s anti-Indian posse. Like many California ghost towns, Kingston was abandoned due to natural disasters that devastated the area. Much like Colonel Allensworth Ghost Town, Kingston represents an important chapter in California’s complex cultural history.

When visiting this ghost town “robbed of existence,” you’ll encounter:

- A seasonal park offering limited recreational access

- Interpretive signage explaining Kingston’s unique history and cultural significance

- Natural landscape that has reclaimed most of the former settlement

The site now reflects both environmental reclamation and the complex legacy of 19th-century Native American displacement in California.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were the Most Common Diseases Affecting Kingston’s Early Residents?

You’d find cholera, diphtheria, and typhus devastated Kingston’s early population, with tuberculosis outbreaks spreading rapidly in crowded living quarters and seasonal smallpox epidemics causing particularly high mortality rates.

Did Any Notable Outlaws or Bandits Frequent Kingston?

Yes, Tiburcio Vasquez and his gang significantly raided Kingston in 1873. While outlaw legends suggest it served as bandit hideouts, historical records don’t confirm other notorious outlaws frequenting the area.

How Did the 1862 Floods Affect Kingston’s Development?

Where pioneers once thrived, floodwaters devastated. The 1862 floods obliterated Kingston’s infrastructure, drowned livestock, and altered settlement patterns permanently. You’ll find this catastrophe directly contributed to Kingston’s eventual abandonment as a viable community.

What Indigenous Languages Were Spoken at the Kingston Rancheria?

Tule-Kaweah Yokuts was primarily spoken at Kingston Rancheria, part of the Yokutsan language family. You’ll find this indigenous heritage remains important in ongoing language preservation efforts throughout the region today.

Were There Any Attempts to Resurrect Kingston After Its Abandonment?

No historical records, no physical evidence, no documented initiatives. You’ll find Kingston lacks any revival efforts following abandonment, with its historical significance preserved only through a marker and seasonal park, not resurrection attempts.

References

- https://www.calexplornia.com/kingston/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD9M6MP6RRU

- https://www.newmexicomagazine.org/blog/post/ghost-towns/

- https://scvhistory.com/gif/galleries/kingston051714/

- https://dornsife.usc.edu/magazine/echoes-in-the-dust/

- https://www.calexplornia.com/california-ghost-towns/

- https://tredcred.com/blogs/trail/ghost-town-overlanding-off-roading-through-california-s-abandoned-history

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingston

- http://www.gribblenation.org/2017/11/kingston-california-and-kingston-grade.html

- https://npshistory.com/publications/usfs/region/5/tahoe/history/chap3.htm