You’ll find Knightsville’s ruins a half-mile east of Eureka, Utah, where Jesse Knight founded his unique mining town in 1896. Unlike typical Western boomtowns, this settlement banned alcohol and vice while focusing on family values. The town thrived with 1,000 residents, 65 homes, and successful silver mines until ore depletion began in 1915. By 1940, Knightsville became a ghost town, though its preserved foundations and cemetery still tell an extraordinary tale of morality meeting mineral wealth.

Key Takeaways

- Knightsville was a unique mining town founded in 1896 by Jesse Knight, known for banning alcohol and maintaining high moral standards.

- The town peaked at 1,000 residents with 65 homes, supported by silver mining operations near Eureka, Utah.

- Unlike typical mining towns, Knightsville had no saloons or red-light districts, focusing instead on family values and education.

- The settlement declined rapidly after 1915 due to ore depletion, becoming a ghost town by 1940.

- Today, visitors can find building foundations, mining artifacts, and a historic schoolhouse listed on the National Register.

The Rise of a Morally-Minded Mining Town

When Jesse Knight founded Knightsville in 1896, he envisioned more than just another mining settlement in Utah’s East Tintic Mountains – he aimed to create a morally upright company town that would defy the typical vices of Western boomtowns.

His discovery of the Humbug mine, initially dismissed by local engineers, provided the economic foundation for his vision. Knight’s devotion to Mormon principles shaped the town’s distinctive character, establishing it as one of the West’s only mining communities without saloons or red-light districts.

The Humbug mine transformed into more than ore – it became the bedrock of a uniquely virtuous frontier town.

You’ll find that community values flourished in this unique settlement, where sixty-five homes, a church, school, and post office supported roughly 1,000 residents at its peak. The town’s success in silver and lead mining made Knight one of the district’s wealthiest individuals. Located one-half mile east of Eureka, Utah, the town’s strategic position near mining operations proved vital to its development.

The strict ban on alcohol and tobacco fostered social cohesion, attracting families seeking a more disciplined lifestyle than traditional mining camps offered.

Life in Knightsville’s Family-First Community

Unlike typical Western mining settlements that catered to transient laborers, Knightsville flourished as a deliberate family-oriented community with 65 homes and two boarding houses supporting roughly 1,000 residents at its peak.

You’d find community values deeply woven into daily life, with the town’s Mormon founder Jesse Knight establishing strict moral codes that prohibited saloons and red-light districts.

Family activities centered around the church, school, and post office rather than the taverns common in other mining camps. Today, dedicated residents continue to explore their ancestors’ lives in Knightsville through genealogical resources on FamilySearch. The town’s infrastructure included essential businesses and services designed to retain families long-term.

You wouldn’t encounter the usual vices of Western mining towns here – instead, you’d experience a wholesome environment where sobriety and clean living shaped the social framework, creating a stable community that prioritized children’s education and family wellbeing.

Mining Operations and Economic Growth

After Jesse Knight arrived in Utah’s Tintic Mining District in 1896, his discovery of the “Humbug” mine transformed the region’s economic landscape. Despite having limited experience, Knight’s mining techniques proved highly successful, leading to unprecedented ore production that established him as one of the district’s wealthiest mine owners.

Throughout the early 1900s, Knight’s operations in the East Tintic area flourished, focusing primarily on silver extraction. As a Latter-day Saints member, Knight established unique workplace policies including the suspension of all mining activities on Sundays.

You’ll find that his mines contributed considerably to Utah’s impressive mineral output, with the state producing over 17 million ounces of gold through 1960. The mining operations supported a thriving economy that peaked with nearly 1,000 residents in Knightsville, sustaining various businesses and community institutions until ore deposits began depleting around 1915, marking the beginning of a gradual decline.

The Final Days of a Silver Empire

The year 1915 marked the beginning of Knightsville’s downfall as rich ore deposits in Jesse Knight’s mines steadily depleted. Nature’s great lottery proved harsh for the mining community as operations struggled to remain profitable.

You’ll find the silver decline accelerated rapidly, transforming this once-thriving mining camp into a ghost town by 1940. Despite the community’s resilience, residents faced mounting challenges as mining operations gradually ceased, leaving only two operational mines by 1924. Like other locations on the place name disambiguation list, this Knightsville has its own unique historical significance.

Knightsville’s fall from silver-rich boomtown to abandoned ghost town mirrors the harsh realities of mining’s boom-and-bust cycles.

- Workers relocated their homes to nearby Eureka as unemployment grew

- The town’s population plummeted from its peak of 1,000 residents

- Economic instability forced the closure of local businesses and services

- Miners struggled with insufficient public relief during periodic recessions

Today, you’ll find little remaining of this former silver empire except the Knightsville School foundation, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, standing as a silent reminder of the town’s fleeting prosperity.

Exploring the Ghost Town’s Remnants Today

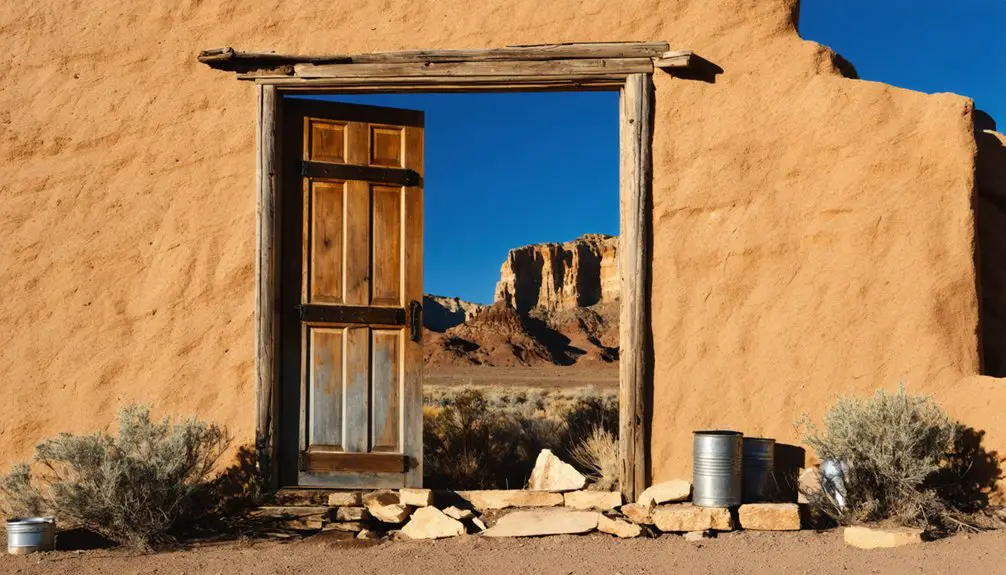

Standing silently on the northern slope of Godiva Mountain, Knightsville’s remnants offer visitors a glimpse into Utah’s mining heritage at 6,742 feet elevation.

As visitors explore the abandoned structures, they may come across the haunting tales of Castle Gate that echo through the canyons. These stories speak of miners who braved treacherous conditions, driven by the hope of prosperity and fortune. Each whisper of the wind carries with it the legacy of those who once called this place home, adding to the mystery that surrounds Knightsville today.

Today, you’ll find the foundations of what once was a thriving community, with the historically significant schoolhouse foundation listed on the National Register of Historic Places serving as a centerpiece for remnant exploration. Like many mining ghost towns, the site stands as a testament to the boom-and-bust cycle of mineral extraction settlements.

The town’s peak saw over 1000 residents in 1907 before its eventual abandonment by 1940.

As you navigate the ghost town’s terrain, you’ll discover scattered mining artifacts and building foundations that tell the story of this unique Mormon-led mining settlement.

Venturing deeper into the area, you’ll also come upon remnants that highlight the history of Harrisburg, Utah, revealing how the community thrived during its peak. These findings not only reflect the challenges faced by the settlers but also their resilience in transforming the harsh landscape into a bustling hub of activity. As you explore, consider the lives of those who once called this place home and the legacy they left behind.

The history of Dewey, Utah ghost town is intertwined with the narratives of countless miners who sought fortune and a fresh start. As you wander through the remnants, you might stumble upon a dilapidated cabin that once provided shelter to weary travelers, telling tales of hope and desperation. Each artifact serves as a poignant reminder of the dreams that fueled this short-lived settlement and its eventual decline.

The well-preserved cemetery and absence of saloon remains set Knightsville apart from typical western mining towns.

While no visitor facilities exist, the site’s accessibility via off-road routes and hiking trails makes it an attractive destination for history enthusiasts seeking to explore these historical artifacts responsibly.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to Jesse Knight After the Town’s Decline?

After your town’s decline, you continued managing diverse mines and businesses while generously supporting the Mormon Church. Jesse Knight’s legacy endures through philanthropy and community development until your death in 1921.

Were There Any Major Accidents or Disasters in Knightsville’s Mines?

You won’t find any major mine safety incidents in historical records. Unlike other Utah mining areas with documented accident reports, Knightsville’s mines operated without catastrophic disasters until their closure around 1940.

What Was the Average Wage for Miners Working in Knightsville?

While there’s no exact record, you’d have earned around $3.00 per day as a Knightsville miner – the regional standard in 1900. Jesse Knight’s fair labor conditions likely meant slightly higher wages.

Did Any Other Businesses Besides Mining Operate in Knightsville?

You’d find several local businesses besides mining, including retail stores, hotels, boarding houses, and a post office. While there weren’t farming practices, the town supported diverse commercial services for residents.

How Did Knightsville’s Education System Compare to Other Mining Towns?

You’ll find their school facilities were more established and permanent, with better educational curriculum standards, thanks to strict moral codes and stable funding, unlike typical mining camps’ makeshift or nonexistent schooling systems.

References

- https://onlineutah.us/knightsvillehistory.shtml

- https://jacobbarlow.com/2015/08/02/knightville-utah/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knightsville

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Knightsville

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/utah/knightsville/

- https://ugspub.nr.utah.gov/publications/uranium_data/MD00573_1.pdf

- https://beyond.nvexpeditions.com/utah/juab/knightsville.php

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/memories/memory/21928773/

- https://historytogo.utah.gov/silver/

- https://universe.byu.edu/2000/03/26/utah-hills-full-of-gold-silver-copper/