You’ll find La Plata ghost town in Utah’s Piny Hills at 7,470 feet elevation, where a horse’s kicked rock led to a spectacular silver discovery in 1891. Within weeks, the site transformed from empty wilderness into a bustling town of 1,500 residents with over 60 buildings. Despite producing $3 million in silver, La Plata’s boom lasted just three years before its dramatic collapse in 1894. Today’s weathered remnants tell a fascinating story of frontier ambition and fate.

Key Takeaways

- La Plata was a silver mining boomtown established in 1891 after P.O. Johnson’s discovery of silver-bearing galena in Utah.

- The town quickly grew to 1,500 residents with over 60 buildings but became abandoned by 1894 due to depleted silver deposits.

- Located at 7,470 feet elevation in Utah’s Piny Hills, La Plata produced $3 million in silver during its peak operations.

- Unlike typical boomtowns, La Plata maintained a peaceful atmosphere with no violent crimes and expelled vice elements to maintain order.

- Today, weathered cabins and mining structures remain on private property, accessible with landowner permission during spring through fall.

The Discovery That Started It All

When P.O. Johnson, a sheepherder, noticed an unusually heavy rock his horse had kicked loose near a sheep trail in July 1891, he couldn’t have known he’d just stumbled upon one of Utah’s richest silver deposits.

A chance kick from a horse’s hoof led to one of Utah’s most valuable silver strikes in 1891.

You’ll appreciate how this chance discovery unfolded when Johnson brought the specimen to his foreman, W. H. Ney, who immediately recognized it as silver-bearing galena.

The assay results revealed extraordinary wealth: ore containing 45% lead and a remarkable 400 ounces of silver per ton.

Much like how Dardo Rocha founded La Plata in Argentina, Ney, recognizing the opportunity, purchased Johnson’s interest for $600 and established the Sundown mine claim.

Their discovery marked the first major mining claim north of Salt Lake City, triggering an unprecedented rush that would transform this quiet mountain location into a bustling frontier town.

The site remains preserved within the rugged terrain of Cache County, Utah, though it now sits on private property.

From Sundown to Silver City

You’ll find La Plata’s origins traced back to the Sundown Mine, where the initial silver claim sparked intense mining activity.

Unlike the many place name references to Silver City across various locations, La Plata carved out its own unique identity in Utah’s mining history. As word of the rich silver-bearing galena spread, the settlement rapidly transformed from a simple mining camp into a bustling frontier town of 1,500 residents with over 60 buildings. Much like Argentina’s La Plata which houses a large oil distillery, Utah’s La Plata also relied heavily on resource extraction for its growth.

La Plata’s meteoric rise and quick decline stands in contrast to the more established Silver City, which maintained operations for decades through its developed infrastructure and diverse mining operations.

Mining Camp Origins

The remarkable origins of La Plata’s mining camp can be traced to a single fortuitous moment in July 1891, when sheepherder Jno. O. Johnson’s horse accidentally chipped a rock along an old sheep trail. The dense rock revealed silver-bearing galena containing 45% lead and 400 ounces of silver per ton, confirmed by assay in Ogden.

You’ll find the early community took shape quickly after Johnson quietly registered his claim. His employer, Ney, purchased the claim for $600 and expanded holdings in the area. The duo initially explored the promising site using only a broken shovel for tools.

The camp’s original name “Sundown” was changed to La Plata, Spanish for “silver,” in August 1891. As mining techniques evolved from simple surface extraction to more organized operations, the discovery sparked a silver rush that transformed northern Utah’s landscape, drawing over 1,000 miners within weeks of the initial find. Within days of the initial settlement, three log cabins were constructed as the first permanent structures in the burgeoning mining camp.

Silver Discovery Sparks Growth

Following Johnson’s momentous discovery, La Plata’s transformation from a quiet sheep trail to a bustling silver town happened at breakneck speed.

When word spread about the shepherd’s silver-rich galena rock containing 400 ounces per ton, you’d have witnessed one of Utah’s most remarkable silver rush migrations north of Salt Lake City.

Fleeting Frontier Fame

While Johnson’s silver discovery sparked the initial rush, La Plata’s most dynamic period unfolded throughout 1891 as more than 1,000 miners descended upon this remote mountain locale.

You’d find a uniquely ordered settlement where community governance emerged through informal camp meetings, setting La Plata apart from typical lawless boomtowns. Despite the transient lifestyles common to mining camps, this settlement maintained remarkable stability.

Three key factors shaped La Plata’s distinct character:

- Local Utah farmers comprised most of the population, not outside drifters

- Zero violent crimes occurred during the town’s existence

- Community-driven expulsion of vice elements preserved social order

Life in a Bustling Mining Town

Despite its remote mountain location, La Plata quickly transformed into a vibrant community of 1,500 residents during the silver boom, offering miners a daily wage of $3 for their labor in the silver-rich mines.

La Plata defied its isolated setting, blossoming into a thriving silver mining town where workers earned $3 daily.

The community dynamics set La Plata apart from typical mining towns – you’d find families settling in rather than the usual rough crowd, and prostitutes were swiftly driven out to maintain social order.

The economic impact rippled through the town’s 60-70 buildings, including stores, saloons, and a bank. You could’ve gotten your water from three different springs, picked up mail at the post office, and joined town meetings at the Liberty pole where residents inscribed their names.

Unlike other frontier towns, La Plata never needed a cemetery – a reflection of its peaceful nature.

The Short-Lived Silver Rush

You’d be amazed how quickly La Plata’s silver rush unfolded after a shepherd’s discovery of silver-bearing galena ore in July 1891, drawing over 1,000 miners within weeks and spawning a bustling town of 1,500 residents.

During its peak, the town’s mines yielded an impressive $3 million in silver production while multiple companies vied to consolidate and capitalize on the rich claims.

Yet by 1894, you’d find nothing but an abandoned ghost town, as the ore veins proved shallow and were rapidly depleted within just three summer seasons.

Discovery Sparks Mining Fever

When a mountain shepherd stumbled upon heavy silver-bearing ore while tending sheep in July 1891, he unknowingly sparked Utah’s northernmost silver rush. The discovery’s economic impact was immediate – Thatcher Brothers Bank quickly purchased the original Sundown Mine claim, while mining techniques evolved from simple prospecting to organized operations.

You’ll find the rush transformed the area with remarkable speed:

- Over 1,500 miners flooded the region within weeks

- About 70 buildings sprang up, including stores, saloons, and a bank

- Miners earned $3 daily, attracting workers from across northern Utah

What made this rush unique was its orderly nature. Unlike typical Old West boomtowns, La Plata’s population consisted mainly of local farmers turned miners, creating a peaceful community that rejected the usual vices of mining camps.

Rapid Rise and Wealth

As investors rushed to capitalize on La Plata’s rich silver deposits in 1891, the region transformed from a remote mountainside into Utah’s most promising mining district.

You’d find a remarkable wealth accumulation as the mines yielded ore containing 400 ounces of silver per ton and 45% lead content, producing $3 million in just three years.

The rapid expansion drew over 1,500 miners at its peak, with workers earning $3 daily.

Major players like the Thatcher Brothers Bank consolidated claims into powerful corporations, while competitors invested heavily in vital infrastructure.

You’ll notice how quickly La Plata evolved into a bustling town of 60-70 buildings, complete with stores, saloons, and essential services.

The mining companies’ investments in transportation and processing facilities turned the area’s mineral potential into tangible economic value.

Dreams Turn to Dust

La Plata’s meteoric rise to prosperity proved tragically brief.

The silver veins that sparked such promise were depleted within just three summer seasons, triggering a swift economic collapse by 1893.

You’ll find that the town’s transient population, largely composed of local farmers-turned-miners, vanished as quickly as they’d arrived.

The mining operation’s downfall stemmed from three critical factors:

- Small, isolated ore pockets rather than extensive veins

- High transportation costs to distant smelters

- Rapid exhaustion of the silver-bearing galena deposits

A Swift Fall From Glory

Despite La Plata’s promising start in 1891 with 1,500 enthusiastic residents, the mining town’s downfall proved brutally swift.

You’d have witnessed a dramatic exodus as harsh winters drove away 90% of the population by January 1892, leaving just 150 hardy souls behind.

The ghost town’s economic collapse accelerated through a perfect storm of challenges.

The richest silver veins quickly depleted, yielding to less profitable deposits. Legal battles in 1892 paralyzed mining operations, while corporate takeovers squeezed out independent prospectors.

When the Panic of 1893 struck, La Plata couldn’t weather the crisis.

What Remains Today

Today, the remnants of La Plata‘s brief but vibrant history lie scattered across the Piny Hills at 7,470 feet elevation, roughly 20 miles south of Logan City.

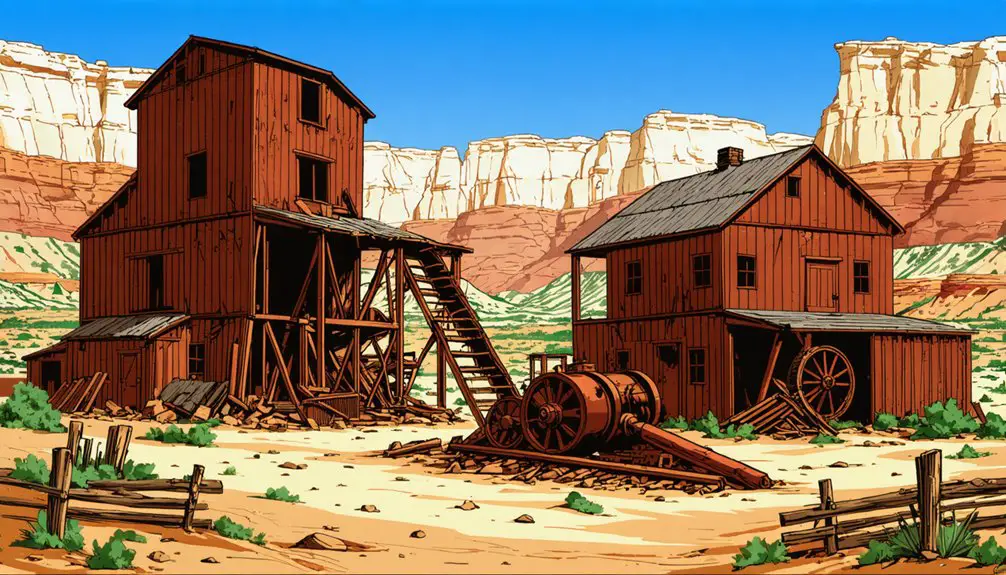

If you’re seeking to explore this ghost town, you’ll find it nestled in the Bear River Mountains on private land totaling 10,800 acres. The site reveals glimpses of its mining heritage through:

- A few weathered cabins showcasing late 19th-century architecture

- Remnant structures from silver mining operations

- Mining-related debris scattered throughout the property

You’ll need the landowner’s permission to visit, but they’re known to welcome explorers.

The best time to access the 2WD-friendly roads is spring through fall, as winter brings heavy snow to these elevations. Many metal detecting enthusiasts have found success exploring the area with proper permissions.

While less preserved than other Utah ghost towns, La Plata’s fragments tell compelling stories of its past.

Like many mining ghost towns across Utah, La Plata’s fate was tied directly to the success and eventual decline of its precious metal deposits.

Preserving La Plata’s Legacy

Preservation efforts surrounding this historic mining settlement blend private stewardship with broader historical initiatives. You’ll find that private landowners have inadvertently protected La Plata’s remaining structures, while programs like the Utah Ghost Town Project work to document and preserve these historical treasures.

Community involvement plays an essential role in preservation strategies. The settlement reached its peak with 30 residents in 1930. Metal detecting enthusiasts contribute valuable historical insights through their careful exploration of the area. You can participate through guided tours, volunteer programs, and educational workshops that connect you with La Plata’s rich heritage.

Local historical societies partner with landowners to facilitate controlled site access and exploration opportunities.

There’s potential for federal funding through agencies like the Bureau of Land Management to support stabilization projects. These efforts could help qualify La Plata for the National Register of Historic Places, ensuring this remarkable piece of Utah’s mining history endures for future generations to explore.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Role Did Native Americans Play in the La Plata Area?

You’d think Native tribes were just passing through, but they fundamentally shaped La Plata’s story – from ancient Puebloans to Utes and Navajos, their cultural impact defined the region’s resource use and territories.

How Did Miners Survive the Harsh Winter Conditions at Such Elevation?

You’d survive harsh winters through clustered log cabin living, stockpiling supplies, wearing layered clothing, and maintaining communal gathering spaces. Your mining techniques adapted to preserve body heat while working outdoors.

Were There Any Major Accidents or Deaths in La Plata’s Mines?

While no major explosions occurred in La Plata’s mines specifically, you’ll find accident reports documenting individual deaths from crushing injuries, coal bursts, and mine collapses – risks that killed thousands across Utah’s mining region.

What Happened to the Mining Equipment After the Town Was Abandoned?

You’ll find the abandoned mining equipment decaying where it stood, with heavy machinery and processing tools left to collapse and deteriorate on private land, never removed or repurposed.

Did Any Families From La Plata Stay in Cache County Permanently?

Time waits for no one, and you’ll find no evidence of lasting family legacy from La Plata in Cache County. Historical records show settlement patterns were transient, with families dispersing elsewhere after the boom ended.

References

- https://usgenwebsites.org/UTCache/hist_laplata.html

- https://mysteryofutahhistory.blogspot.com/2015/09/1891-second-la-plata.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Plata

- https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=history_facpub

- https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/history_facpub/15/

- https://onlineutah.us/laplata_history.shtml

- https://kids.kiddle.co/La_Plata

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_City

- https://ugspub.nr.utah.gov/publications/open_file_reports/ofr-695.pdf

- https://westernmininghistory.com/mine-detail/10087291/