You’ll find Latuda’s abandoned ruins in Utah’s Spring Canyon, where Liberty Fuel Company established a thriving coal mining town in 1914. At its peak in the 1920s, the community housed 343 residents in 55 wooden homes, with daily coal production reaching 1,600 tons. The town struggled through the 1950s as coal prices fell, finally closing in 1966. Today, weathered structures and local legends, including the haunting White Lady of Spring Canyon, tell deeper stories of this once-bustling community.

Key Takeaways

- Latuda was a coal mining town established in 1914 by the Liberty Fuel Company, reaching its peak in the 1920s with 343 residents.

- The town featured 55 wooden homes, a stone mine office, and produced up to 1,600 tons of coal daily during peak operations.

- Economic decline, harsh winters, and falling coal prices led to the mine’s closure in 1966, resulting in the town’s abandonment.

- The famous “White Lady” ghost story, linked to mining tragedies, continues to attract visitors to the abandoned town site.

- Today, concrete foundations, cellar holes, and the ruins of the 1920 Liberty Fuel Mine office remain as historical landmarks.

The Birth of a Coal Mining Community

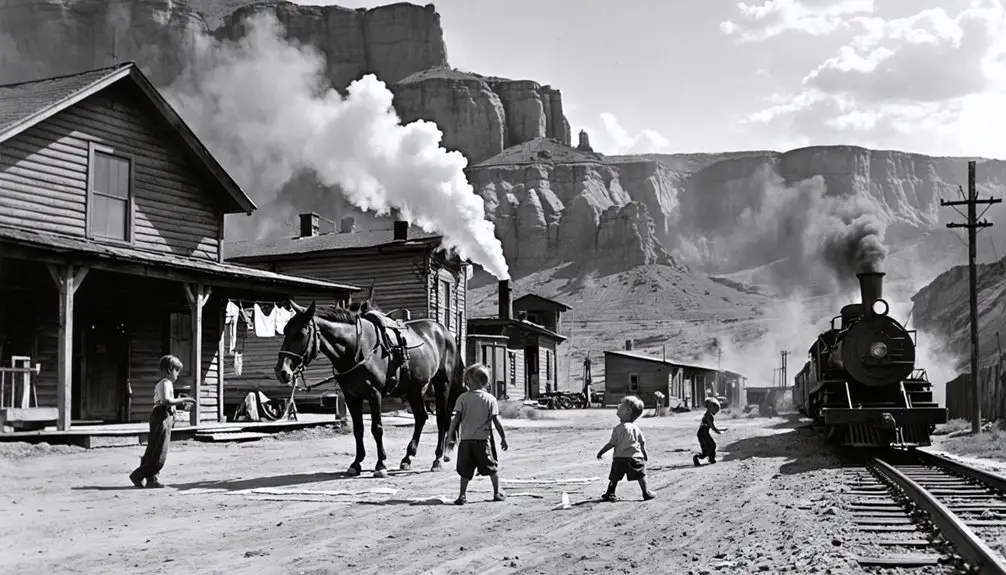

When prospectors discovered coal in 1914, they set the foundation for what would become the thriving mining community of Latuda, Utah.

Frank Latuda and his partners established the Liberty Fuel Company, with Charles Leger, John Forrester, and Frank Gentry leading initial development work alongside Frank Cameron.

In 1918, the growing community saw the construction of twenty company homes to house the increasing workforce.

The company relied on the Carbon company tracks to transport their coal shipments from Latuda during mining operations.

Life in Liberty Fuel Company’s Town

As Liberty Fuel Company established its foothold in 1918, life in Latuda centered entirely around coal production and the company’s management of daily affairs. Under superintendent George A. Schultz‘s 25-year leadership, the community dynamics reflected both control and stability. The town was officially renamed Latuda in 1923 to distinguish it from other Liberty-named settlements.

You’d find yourself among 343 residents by 1920, mostly foreign-born miners and their families, living in company-built housing that expanded from 20 to 55 houses by 1922.

- Your workday would revolve around mining operations producing up to 1,600 tons daily.

- You’d shop at the independently-owned grocery store, unique among mining towns.

- Your neighbors would include immigrant workers who enriched the cultural fabric.

- Women in your community would maintain essential roles at the boarding house.

- Your social life would intertwine with mine schedules and community gatherings.

Architecture and Town Planning

Built to accommodate the Liberty Fuel Company’s workforce in 1918, Latuda’s distinctive layout featured three long rows of houses stretching east to west along Spring Canyon.

The town layout was purposefully designed to maximize the narrow canyon’s usable space, with modest wood-frame homes serving as the primary architectural feature. The land had previously been home to Fremont Indians who left their mark through ancient rock art.

You’d find basic one-story houses throughout the community, lacking indoor plumbing until 1945. The architectural characteristics reflected standard coal camp designs, with company employees likely handling the construction using readily available materials and plans. The mine reached impressive production levels of 1600 tons daily during its peak years of operation.

While supervisory staff enjoyed slightly larger homes, there wasn’t a strict housing hierarchy based on ethnicity or status.

Unlike typical company towns, Latuda operated without a company store, though it maintained essential facilities like a mine office and boarding houses near the mining operations.

Mining Operations and Economic Impact

Beyond the town’s architectural layout, the Liberty Fuel Company‘s mining operations shaped Latuda’s economic foundation from its earliest days.

You’ll find that Francisco Latuda’s vision for mining technology transformed 326 acres of coal lands into a thriving operation by 1917. The Liberty Mine’s economic resilience showed through its steady 1,600-ton daily output during the 1930s, even as other towns struggled through the Depression. The mine was part of a larger network that helped extract 43 million tons of coal from the Spring Canyon area. The underground fires that started during operations continue to burn today, creating morning haze over the hillside.

- Advanced tramway systems transported coal down steep canyon walls

- Independent grocery store broke the typical company-town model

- Immigrant workforce of 343 residents by 1920 drove production

- Boarding houses created additional income streams for local families

- Daily output included diverse coal types: slack, stove, lump, and nut

The mine’s consistent operations sustained both local and regional economies until its closure in 1966.

The White Lady Legend

You’ll encounter one of Utah’s most enduring ghost stories in Spring Canyon, where the White Lady allegedly haunts the abandoned Latuda mine entrance and Liberty Mine office.

According to local folklore dating back to the 1960s, this spectral figure in white appears as a pale-faced woman floating above ground, with various accounts linking her origins to a tragic mining family’s tale of loss and despair.

The ghostly figure frequently appears during October evenings, creating an especially haunting atmosphere for those brave enough to visit the site. Reports from visitors and paranormal enthusiasts describe unexplained sensations of being watched near the mine entrance, with the ghost reportedly vanishing just before reaching the old mining office, making this legend a significant part of Carbon County’s cultural heritage. After escaping from a mental health facility, the distraught woman searched endlessly for her drowned baby before becoming a haunting presence in the canyon.

Origins of Ghost Story

Legends surrounding the mysterious White Lady of Latuda emerged during the town’s mining heyday, drawing from both historical tragedies and regional folklore.

You’ll find her story deeply rooted in the harsh realities of mining life, where accidents, avalanches, and rockslides claimed numerous lives. After her husband’s death, she sought help from the mine officials but failed.

Multiple origin stories tell of a woman’s tragic fate – whether through suicide after losing her husband, drowning with her child, or dying in a confrontation with mine officials.

- Reports of ghostly encounters intensified during the 1960s

- Her legend parallels La Llorona, another weeping spirit of the Southwest

- Local teenagers and thrill-seekers frequently explored her haunting grounds

- The story evolved to reflect the community’s need to process mining tragedies

- She’s seen as both a warning spirit and a victim of corporate negligence

Tragic Mining Family History

While the White Lady’s legend grew from Latuda’s mining tragedies, the real story begins with Francisco Latuda and Charles Picco’s 1917 purchase of 326 acres for the Liberty Mine.

The Latuda family, originally from Trinidad, Colorado, brought their mining expertise to Utah, where they’d establish a thriving company town of 343 residents by 1920.

You’ll find their story marked by both success and heartbreak. The family operated a boarding house while developing the Liberty Mine, which modernized with mechanical loading in 1926.

But mining accidents cast dark shadows – devastating snow slides in 1927 killed two miners and destroyed homes.

When Frank Latuda died in 1931, he left behind a legacy of mining development tainted by the harsh realities of coal mining life, where family tragedies and industrial accidents were all too common.

Reported Paranormal Encounters

Among Utah’s most enduring ghost stories, the White Lady of Latuda has captivated locals and visitors since the town’s mining era.

You’ll find reports of paranormal sightings describing a spectral woman in white, floating several feet off the ground near the abandoned mines. Witnesses claim she appears with a pale, empty face, expressing both sorrow and vengeance.

- Appears as both a warning spirit and a malevolent entity luring miners to danger

- Creates unexplained green lights and eerie sensations throughout the canyon

- Parallels the Southwest’s La Llorona legend, mourning lost children

- Inspired a 1969 attempt to “kill the ghost” with explosives

- Continues drawing thrill-seekers to ghostly encounters in the ruins

Local interpretations suggest she’s a tragic figure caught between worlds, unable to find peace after losing her family to the mines’ dangers.

Daily Life in Latuda’s Heyday

During Latuda’s peak years from 1918 to the late 1920s, daily life centered around the Liberty Fuel Company‘s coal mining operations, which produced up to 1,600 tons of coal per day.

You’d find miners and their families living in one of the 55 wooden homes that replaced the initial tents, marking the town’s evolution from a temporary camp to an established community.

The stone mine office served multiple purposes – you could visit the doctor there, and executives would stay in the top-floor hotel.

Community resilience showed in how residents handled challenges like water shortages and dangerous snow slides.

The school building became the heart of social gatherings, where you’d join your neighbors for meetings and events, creating bonds that helped the isolated mountain town thrive at 6,700 feet elevation.

The Path to Abandonment

As you’d expect in a mining town, Latuda’s fate hinged directly on its coal production, which by the 1930s had declined considerably with operations running as little as one day per week.

Throughout the following decades, you’d have seen the town’s population steadily decrease as mechanical loading replaced workers and the mine struggled to maintain consistent operations.

The final blow came in 1966 when the Liberty Mine closed permanently, its portal was blasted shut, and the remaining families left their homes behind, leaving only empty buildings to mark what had once been a bustling coal camp.

Economic Decline Hits Hard

The economic foundation of Latuda began crumbling when coal production at Liberty Fuel Mine dropped from its peak of 1,600 tons per day to roughly 1,000 tons by the mid-1940s.

Despite community resilience, economic hardships intensified as coal market prices fell throughout the 1950s, forcing Liberty Fuel Company to drastically reduce operations by 1954.

- Mine workers faced reduced shifts – often just one day per week

- Company town residents lived under constant threat of eviction

- Population declined from 400 as families sought work elsewhere

- Limited water resources and harsh winters compounded challenges

By 1966, plummeting coal demand forced the mine’s permanent closure.

The devastating combination of market forces, environmental challenges, and declining infrastructure ultimately led to Latuda’s complete abandonment by 1967, marking the end of this once-thriving mining community.

Mining Operations Wind Down

Once Liberty Mine began winding down operations in the early 1950s, its workforce faced increasingly limited shifts and declining production levels.

Despite earlier technological advances, like the 1926 introduction of mechanical loading to improve efficiency, the mine couldn’t sustain its operations against mounting economic pressures.

You’ll find that community dynamics shifted dramatically as miners and their families left to seek work elsewhere.

The mine’s 1954 closure dealt the final blow, shuttering not just the mining operation but also essential community institutions.

The town’s infrastructure, including company housing and the stone mine office, fell into disrepair without maintenance funds.

While Latuda had modernized with indoor plumbing in 1945, these improvements couldn’t save the town from its inevitable fate as workers dispersed between 1954 and 1967.

Empty Houses Tell Stories

Today’s empty houses in Latuda stand as weathered monuments to a community’s gradual dissolution, with their sagging roofs and broken windows telling poignant stories of abandonment.

These abandoned structures whisper tales of the harsh realities that drove residents away – from the devastating 1927 snow slides to the Liberty Mine’s final closure in 1966.

You’ll find evidence of lives suddenly interrupted, where wooden frames have weathered decades of neglect at 6,700 feet elevation. The empty buildings have also spawned ghostly encounters, including the famous “White Lady” sightings that attract curious visitors.

- Original 1920s miners’ homes now stand as silent shells

- Snow slides damaged vital infrastructure and homes

- Depression-era layoffs forced families to seek opportunities elsewhere

- Water scarcity plagued residents throughout the town’s history

- Youth vandalism, including the 1972 mine office dynamiting, accelerated decay

Remnants and Ruins Today

While most of Latuda’s original 55 homes from 1922 have vanished, visitors can still find scattered concrete foundations and cellar holes throughout the former townsite.

The Liberty Fuel Mine office building from 1920 stands as one of the few mining-related structures near the canyon floor, marking its historical remnants significance.

You’ll discover large brick and wood mining buildings partially intact, alongside abandoned rail lines and an old railroad bridge in Spring Canyon.

The industrial scale of coal mining operations is evident through remaining infrastructure like loading docks and slag piles.

These physical markers of cultural heritage, though weathered and sometimes vandalized, tell the story of Latuda’s mining past.

Rusted equipment and mining hardware scattered among the ruins further illustrate the town’s industrial legacy.

Exploring Spring Canyon’s Mining Heritage

Spring Canyon’s rich mining heritage began in 1895 with the first coal mine at Storrs, setting off decades of industrial development throughout the region.

You’ll discover how mining technology evolved from early tramways to sophisticated coal transport systems, while towns like Latuda, Standardville, and Peerless emerged to support the booming industry.

- Explore the site of Liberty Mine, opened in 1914 by Frank Latuda and Frank Cameron

- Walk where miners once transported coal down steep canyon walls via tramways

- Visit the remnants of a once-thriving 35-home community

- See the historic location of the rock schoolhouse that served mining families

- Stand where the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad once hauled coal

This coal heritage story showcases the determination of early pioneers who transformed Spring Canyon into an essential energy production center, lasting until its abandonment in 1967.

Preserving Latuda’s Memory

You’ll find Latuda’s story preserved through detailed Historic American Buildings Survey documentation and photographic archives that capture the Liberty Fuel Company’s operations from 1918-1954.

The town’s memory lives on through vivid oral histories and ghost stories, particularly the enduring legend of the “White Lady of Spring Canyon” that has circulated since the 1960s.

While physical remnants like the dynamite-damaged mine office remind visitors of darker chapters, local historical societies and online communities continue sharing Latuda’s rich mining heritage through tours and digital platforms.

Historical Documentation Efforts

As historians and preservationists work to document Latuda’s legacy, several key organizations have contributed to maintaining the town’s historical record.

Through extensive archival preservation efforts, you’ll find detailed documentation spanning from the town’s 1917 beginnings to its 1966 closure.

- Liberty Fuel Company records provide essential mining operation details and company policies

- The 1988 Historic American Engineering Record offers detailed architectural documentation

- Census records from 1920 reveal a diverse community of 343 residents

- Local newspaper archives chronicle major events, including the tragic 1937 rock fall

- Historical associations in Carbon County continue collecting oral histories and photographs

The historical records paint a vivid picture of life in this Utah mining town, from its multicultural workforce to the challenges of daily existence in Spring Canyon.

Community Storytelling Traditions

Through decades of social gatherings and oral traditions, Latuda’s residents wove rich tapestries of local folklore that continue to shape the ghost town’s cultural identity.

In story circles at the 1921 schoolhouse, mine office hotel, and boarding houses, miners and families shared tales of daily life and mining accidents, strengthening their collective memory.

The most enduring legend remains the “White Lady of Spring Canyon,” reportedly haunting the Liberty Mine entrance and office.

You’ll find this ghost story has sparked numerous teenage gatherings since the 1960s, even leading to one youth’s attempt to “exorcise” the spirit with dynamite.

These oral traditions, anchored to specific locations like Frank Latuda’s original mining camp, have preserved the community’s heritage long after its abandonment, connecting past residents through shared narratives of hardship and resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Residents of Latuda After the Town Was Abandoned?

You’ll find former residents scattered across Carbon County by 1967, with many settling in Helper. While their town legacy lives on through folklore, residents’ fate involved seeking jobs elsewhere.

Were There Any Major Mining Accidents or Disasters in Latuda’s History?

While no major disasters struck, you’ll find the most significant incident was a deadly rock fall in 1937 at Liberty Fuel Company’s mine. Mining safety records show it killed one, injured two miners.

How Did Children Receive Education Before the School Was Established?

You’d find children learning in company houses through informal home schooling and community gatherings starting in 1918, with miners’ families and community members teaching before the 1921 schoolhouse construction.

What Other Ethnic Groups Besides Japanese Lived and Worked in Latuda?

Working alongside Japanese miners, you’d have found Swedes, Inlanders, and Slavs contributing to Latuda’s diversity, while Italian families ran the local grocery store and boarding house for miners.

Did Any Original Latuda Buildings Get Relocated or Preserved Elsewhere?

While records show buildings were moved after 1967’s abandonment, you won’t find any documented cases of preserved Latuda structures. The historical significance was lost as buildings were dismantled without formal preservation efforts.

References

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ut-springcanyonlady/

- https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0200/ut0267/data/ut0267data.pdf

- https://www.utahoutdooractivities.com/four-utah-ghost-towns.html

- https://www.roadtripryan.com/go/t/utah/carbon-county/spring-canyon

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Latuda

- https://ogm.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/TurriFinal.pdf

- https://utahrails.net/utahcoal/peerless.php

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=265662

- https://jacobbarlow.com/2022/11/21/liberty-fuel-latuda-utah/

- https://utahrails.net/utahcoal/spring-canyon-mines.php