Masonic, a remote California ghost town sitting at 8,000 feet elevation, began with an 1860 gold discovery but flourished after 1900 when the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine yielded rich ore worth up to $800 per ton. You’ll find the unique three-section settlement (Upper, Middle, and Lower Town) abandoned after legal disputes and declining gold deposits led to its demise by the 1950s. The haunting ruins offer glimpses into Sierra Nevada mining’s boom-and-bust cycle.

Key Takeaways

- Established in 1860 after gold discovery, Masonic grew into a thriving mining town at 8,000 feet elevation in California’s Sierra Nevada.

- The town featured three distinct settlements (Upper, Middle, and Lower Town) connected by telephone lines in 1905.

- Masonic’s prosperity peaked around 1907-1911 with a ten-stamp mill that processed ore valued up to $800 per ton.

- Legal disputes, mechanical failures, and depleted ore deposits led to Masonic’s decline, with complete abandonment by the mid-1950s.

- Today, stone cabin ruins, the Pittsburg-Liberty Mill remains, and tramway fragments stand as haunting reminders of this once-thriving mining community.

The Gold Discovery That Started It All (1860-1900)

While many of California’s mining towns boomed in the 1850s, Masonic’s story began slightly later when prospectors from nearby Monoville discovered gold ore in the district during the summer of 1860.

These early prospectors, mainly members of the Freemasons, lent their brotherhood’s name to the area—establishing the Masonic Mining District at an elevation of 8,000 feet near the California-Nevada border.

Despite initial discoveries, the site remained largely undeveloped for decades as miners flocked to more accessible strikes in Aurora and other boom towns.

The promise of Masonic’s riches lay dormant while fortune-seekers chased dreams in neighboring boomtowns.

It wasn’t until 1900 that sixteen-year-old Joe Green from Bodie rediscovered the area’s potential, staking a claim at what became the Jump Up Joe Mine.

Though Green quickly sold his find to Warren Loose, his discovery sparked renewed interest and infrastructure development that would transform this remote Freemason influence into a thriving mining community. The district, situated just 1-1/2 miles west of Nevada, would soon become a focal point for gold seekers throughout the region. Unlike its notorious neighbor Bodie, Masonic developed a reputation for being a remarkably peaceful settlement.

Three Towns Become One: The Unique Layout of Masonic

The discovery of gold that fueled Masonic’s development resulted in a highly unusual settlement pattern rarely seen in Western mining towns.

As you explore this ghost town‘s remains today, you’re actually walking through what was once three distinct settlements—Upper Town (originally Lorena), Middle Town, and Lower Town (formerly Caliveda)—positioned along a canyon’s natural terraces.

- Upper Town functioned as the administrative center, housing mine offices before the administrative merging.

- Middle Town emerged as the commercial hub with hotels, stores, and social infrastructure.

- Lower Town anchored the district with the massive Pittsburg-Liberty Mill.

The town layout followed the canyon’s vertical topology, with settlements stacked half-mile apart.

Telephone lines installed in 1905 connected all three segments before formal unification in 1906.

The Freemason founders who discovered gold in the 1860s established the initial settlement of Lorena before the town expanded into three distinct areas.

Despite the town’s proximity to Bodie, Masonic maintained a peaceful reputation throughout its existence, with remarkably low crime rates compared to neighboring mining communities.

Golden Years: The Rise of the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine

As you approach the ruins of the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine, you’re walking on ground that once yielded a spectacular $4,000 gold nugget that sparked Masonic’s rapid growth in the early 1900s.

The mine’s ten-stamp mill, constructed in 1907, processed ore valued at up to $800 per ton and employed fifty workers during its peak operations.

Connecting the mining operations to the mill, an innovative aerial tramway system was installed across the canyon in 1913, representing the last major infrastructure investment before the mine’s inevitable decline.

The mine was named in honor of Phillips’ hometown and Independence Day when gold was struck on July 4th, 1902.

The Stall brothers’ acquisition in 1913 brought a brief resurgence of activity to Masonic before operations gradually wound down toward abandonment.

Striking $4,000 Gold Nugget

One remarkable feature of Masonic’s early mining history centers on the discovery of an extraordinary $4,000 gold nugget during the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine’s heyday.

This striking nugget emerged during the peak production years following the 1902 discovery, contributing to the mine’s legendary status among California gold legends. Similar to Frederic Rochon’s discovery that weighed fifteen pounds and created a mining boom, this find generated tremendous excitement in the region.

You’ll find that such exceptional finds fueled the rapid expansion of Masonic’s three distinct townsites.

- Assay values reached an astonishing $800 per ton at Pittsburg-Liberty

- The spectacular nugget represented roughly five times an average miner’s annual salary

- Local prospectors celebrated such finds with renewed claim-staking throughout the district

- These discoveries temporarily overshadowed the litigation troubles plaguing the operation

- Gold specimens of this caliber validated the Freemasons’ original 1860 district establishment

Mining historians often compare these valuable finds to those from the Burgess Mine, which shares similar historical significance in California’s rich gold mining heritage.

Ten-Stamp Mill Operations

Serving as the industrial centerpiece of Masonic’s golden era, the ten-stamp mill constructed by the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine transformed the district’s production capabilities when it began operations in September 1907.

This steam-powered facility, built by Joshua Hendry Iron Works of San Francisco, eliminated costly ore shipping by wagon.

You’d witness impressive stamp mill efficiency as 50 workers processed 30-35 tons of ore daily across three shifts. The operation utilized amalgamation techniques where mercury captured gold particles from ore crushed fine enough to pass through 40-mesh screens. Each stamp was individually lifted by rotating cam shafts, creating the rhythmic pounding sounds that echoed throughout the valley.

By 1908, they’d added a cyanide plant to increase gold recovery from tailings.

The mill’s success prompted expansion with the additional Chilian Mill in 1910 and a half-mile aerial tramway in 1913, ultimately producing approximately $700,000 in bullion. At its peak between 1906 and 1911, Masonic became the premiere ore producer on the California-Nevada border.

Canyon Tram System

The Canyon Tram System revolutionized ore transportation at Masonic when the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine installed an advanced aerial tramway connecting their mining operations to the processing facilities in Lower Town.

This mining infrastructure solution overcame the challenging topography of Masonic Gulch, enabling efficient movement of gold-rich ore that assayed at an impressive $800 per ton.

- Strategic tram tower constructed on the hill south of the mill to support the aerial transport system

- Designed specifically to handle high-grade ore from the Pittsburg-Liberty’s productive veins

- Eliminated need for laborers to manually haul ore down steep canyon walls

- Functioned as the literal lifeline between extraction points and processing operations

- Represented technological adaptation to the remote wilderness setting of the mining district

Daily Life in a Remote Mining Community

Life in Masonic unfolded across three distinct terraces that formed the town’s unique geographical structure, with each level serving a specific purpose in the community’s daily functioning.

You’d find most residents traversing between Middle Town‘s businesses and their simple wooden cabins scattered throughout the settlement. Community dynamics centered around the mining schedule, with men working grueling 8-12 hour shifts six days weekly, earning $2-4 daily at the Pittsburg-Liberty or Jump Up Joe mines.

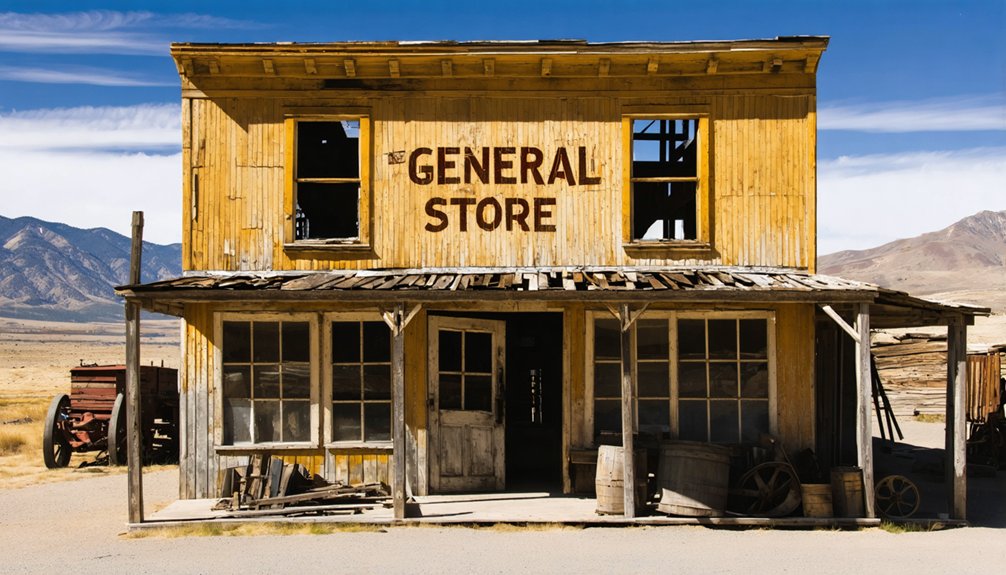

Daily routines revolved around practical necessities—gathering water from nearby streams, visiting the general store for supplies, and perhaps unwinding at the local saloon after work.

Children attended the schoolhouse when mining cycles permitted, while families shared cramped quarters in basic cabins lacking insulation. Despite harsh conditions, social gatherings and community events provided essential respite from the isolation.

The Slow Fade: Masonic’s Decline and Abandonment

You’ll find Masonic’s golden promise faded quickly after 1911, when shallow ore deposits proved unsustainably distributed despite initial assays of up to $800 per ton.

The mine’s decline accelerated through damaging legal disputes between the Pittsburg-Liberty Mine and its general manager, diverting critical resources while mechanical failures plagued the Chilean Mill’s processing capabilities.

Mining Fortunes Evaporate

Once soaring with economic promise and geological fortune, Masonic’s mining operations began their irrevocable decline following John Phillips’ mysterious death in 1909, marking a pivotal turning point in the town’s prosperity.

You can trace Masonic’s economic fluctuations through its rapid descent from boom to bust. Despite advanced mining techniques including aerial tramways and stamp mills, the region’s wealth literally vanished underground as high-grade ore bodies disappeared.

- Ore that once assayed at $800 per ton became increasingly scarce

- Multiple ownership changes failed to revitalize production

- The 10-stamp mill closed permanently by 1920

- Brief revivals in the 1920s and 1950s proved financially unsustainable

- Southern Pacific Railroad’s abandoned plans to build connecting lines reflected the mine’s diminishing value

Legal Battles Doom Progress

The lengthy shadow of litigation ultimately proved as devastating to Masonic’s survival as the depletion of its precious metals.

You can trace the town’s demise through endless legal battles over land ownership and mine leases that paralyzed operations throughout the 1920s and 30s.

These courtroom conflicts forced repeated dismantling and reconstruction of the Chemung mill, creating prohibitive expenses that couldn’t be justified by diminishing returns.

When combined with depressed gold prices and high transportation costs to Bodie’s smelter, even promising ore strikes couldn’t sustain profitability.

Population Dwindles Rapidly

While mining operations sputtered through legal entanglements, Masonic’s population underwent an even more dramatic collapse, transforming from a bustling frontier settlement to a near-empty shell within a single decade.

By 1920, demographic shifts had reduced this once-promising camp to just 12 residents. The post office’s closure in 1912 (briefly reopened in 1913) signaled the beginning of the end, with services transferred to distant Bridgeport.

Despite occasional discoveries of new ore veins offering temporary hope, the population loss proved irreversible.

- You’d find only 12 registered voters in 1924

- No churches or fraternal organizations existed to sustain community life

- World War II’s ban on gold mining delivered the final blow

- By mid-1950s, the town stood completely abandoned

- Only decaying buildings remain as silent witnesses to Masonic’s brief existence

What Remains: Exploring Masonic’s Ruins Today

Nestled between the rugged Sweetwater Mountains and Bridgeport Valley, Masonic’s ghostly remnants tell a compelling story of boom and abandonment.

You’ll discover stone cabin ruins scattered throughout Middle Town, the impressive timbered frame of the Pittsburg-Liberty Mill, and parts of the aerial tram system that once transported ore.

During your ruins exploration, you’ll encounter concrete foundations where machinery once operated, alongside remnants of railroad lines and dangerous mine shafts.

The main three-tier mine structure stands remarkably preserved after 150 years. Local ghost stories add another dimension to your visit—particularly that of John Phillips, whose spirit allegedly haunts the Chemung Mine on Saturday nights.

This remote site, accessible via a 12-mile drive from Bridgeport, offers an unpolished, authentic glimpse into Sierra Nevada mining history.

Preserving the Legacy of a Peaceful Mining Settlement

Unlike many of its rowdier Sierra Nevada counterparts, Masonic’s enduring legacy rests on foundations of fraternal peace rather than frontier violence. This unique heritage stems directly from its Freemason founders, whose fraternal values shaped a community markedly different from notorious boom towns like Bodie.

Preservation efforts now focus on maintaining this distinctive mining heritage through educational initiatives and physical conservation.

- Historic plaques emphasize Masonic’s peaceful origins tied to Freemason principles

- Remnants of the Pittsburg-Liberty Mill stand as testimony to the district’s industrial past

- Interpretive signs contrast Masonic’s orderly society with lawless contemporaries

- Foundations across three distinct townsites illustrate the community’s organized structure

- Documentation projects by historical societies preserve narratives of fraternal cooperation

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Paranormal Activities or Hauntings Ever Reported in Masonic?

Yes, you’ll discover numerous documented reports of poltergeist phenomena, especially on Saturday nights. Ghost sightings and local legends often connect these manifestations to John Phillips’ mysterious 1909 mining shaft death.

What Happened to the Residents After Masonic Was Abandoned?

You’ll find Masonic residents primarily relocated to nearby towns like Bridgeport or Bodie. Some sought opportunities in Nevada mining centers, while others shifted to agriculture and ranching throughout the region’s ghost town changes.

How Did Miners Survive Harsh Winters at Masonic’s Elevation?

You’d survive Masonic’s brutal winters by gathering supplies early, insulating your cabin, participating in communal resource sharing, rotating fire-tending duties, and adapting mining techniques to accommodate seasonal challenges at 6,000-7,000 feet.

Why Didn’t Masonic Experience the Lawlessness Common in Other Mining Towns?

Masonic’s Freemason foundation established structured community dynamics and informal local governance, while its isolation, manageable population, and fraternal order ethics prevented the lawlessness you’d typically find in gold rush settlements.

Are There Any Remaining Artifacts Visitors Can Legally Collect Today?

While you might desire souvenirs, you can’t legally collect historical artifacts from Masonic. Legal regulations strictly prohibit removing any mining relics, structures, or archaeological materials to guarantee proper artifact preservation for future generations.

References

- https://www.destination4x4.com/masonic-california-ghost-town/

- https://sierrarecmagazine.com/discover-masonic-ghost-town-and-so-much-more-4×4-near-bridgeport/

- https://nvtami.com/2020/06/26/masonic-california/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yW1UJyDbOpg

- https://beyond.nvexpeditions.com/california/mono/masonic.php

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/california/masonic/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/masonic

- https://www.youtube.com/shorts/zh3Jf_Azbak

- https://www.deluciaoutdoors.com/masonicmine.html

- https://sweetamericanasweethearts.blogspot.com/2015/08/masonic-and-its-mines.html