Maxton sits on Mt. Union’s northwest shoulder in Yavapai County, Arizona, where the Senator Mine sparked a brief boom during the 1860s gold rush. You’ll find this former stage stop once served 3,500 residents between Prescott and the Colorado River, with its post office operating from 1901 to 1905. The Senator Mine’s extensive tunnel system produced roughly $530,000 in gold before operations ceased around 1907. Today, only ore tracks and scattered foundations mark where Max Alwen’s general store and saloon once stood along these scenic canyon sides, inviting further exploration of its vanished prosperity.

Key Takeaways

- Maxton was a 1860s mining community in Yavapai County, Arizona, near the Senator Mine, briefly operating a post office from 1901 to 1905.

- The town thrived as a stage stop between Prescott and the Colorado River, serving miners with a general store, saloon, and postal services.

- Senator Mine featured extensive underground tunnels totaling 15,000 feet, producing approximately $530,000 in gold from high-grade ore deposits.

- Mining declined after 1900; the post office closed in 1905, and operations ceased by 1907, leading to the town’s abandonment.

- Today, only mining relics like ore tracks remain; visitors should avoid mine shafts and respect no trespassing signs for safety.

Location and Geographic Setting

Nestled in the rugged terrain of Yavapai County, Arizona, the ghost town of Maxton occupies a canyon-side location at the head of the Hassayampa River valley. It is approximately 200 feet from the Senator Mine‘s entrance on the northwest shoulder of Mt. Union.

Maxton clings to canyon walls near the Senator Mine, a weathered sentinel at the Hassayampa River valley’s remote headwaters.

The site’s geographic significance stems from its precise positioning at N 34° 24′ 58″ by W 112° 24′ 40″ within township T12N, R2W, placing it firmly within central Arizona’s mineral belt south of Prescott.

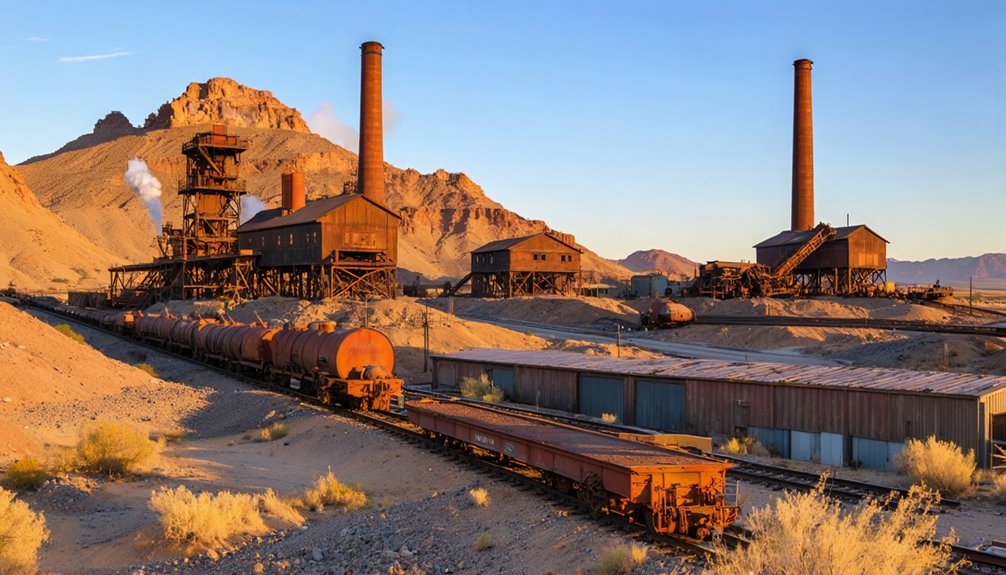

Landscape features define accessibility and settlement patterns here. You’ll find structures scattered across both canyon sides, with the Max Alwen store foundation positioned roadside while mine operations occupy the opposite slope. Visible ore tracks traverse the terrain between extraction and processing sites, demonstrating the industrial scale of historical operations. A ten-stamp mill was constructed one mile from the mine on Hassayampa Creek, serving the Senator Mine’s ore processing needs.

The 2WD-accessible roads make exploration feasible year-round. Good hiking opportunity exists from the canyon side to Maxton, allowing visitors to traverse the historic landscape on foot.

Early Settlement and Post Office Era

The post office at Maxton officially opened on July 6, 1901, establishing the settlement’s identity near the Senator Mine discovered decades earlier in the 1860s.

You’ll find documented evidence of the community’s operations through primary sources like Max Alwen’s October 21, 1903 billhead, which shows his general store functioned as the central hub for mail, stages, and provisions.

This brief four-year period before closure on February 15, 1905 represents the town’s entire official existence under Arizona Territory records. Like other Bradshaw Mountain settlements, Maxton served miners working claims high in the mountains, where remote locations created significant logistical challenges for ore transportation and community sustainability. The town experienced rapid growth during its mining peak years, a pattern common throughout Arizona’s territorial mining communities.

Founding Near Senator Mine

How did a remote mining discovery in Arizona’s Bradshaw Mountains transform into the settlement of Maxton? You’ll find its origins in the 1860s Senator Mine, discovered near the Hassayampa River‘s headwaters during the Bradshaw gold rush. The mine’s name reflects local folklore about Arizona politicians with Senate aspirations who invested in the operation.

Initial development began before 1871, though Apache attacks repeatedly disrupted work. By 1881, operations expanded profoundly with the Senator Shaft reaching 200 feet and supporting infrastructure emerging.

When Phelps Dodge acquired the property in the 1890s, they transformed the rough mining camp into a proper town. The settlement spread along the steep Hassayampa banks and Senator Highway—Arizona’s first toll road. The mine was accessible via Senator Highway from Prescott, connecting the remote camp to the territorial capital. A dam was constructed on the Hassayampa River to provide water supply for both the town and mining operations.

Historical architecture emerged as hotels, saloons, a church, and school replaced the original tents and boarding house.

Post Office Operations 1901-1905

As Maxton’s physical infrastructure took shape in the 1890s, the settlement’s administrative identity solidified with federal postal recognition by 1905. You’ll find Marella T. Alwens serving as postmaster during the 1905-1906 period, managing mail routes that connected miners and residents to broader territorial networks.

The Maxton post office appears in official directories alongside larger operations like Mayer and Dewey, though without the population statistics or railway connections those communities enjoyed. This postal history reveals a working settlement rather than mere mining camps—federal recognition required demonstrable population and commercial activity. Oliver L. Geer later assumed postmaster duties, continuing mail operations for the scattered mining community.

The office handled basic correspondence without rural carrier routes, typical for remote Yavapai County locations. Like other short-lived territorial posts, Maxton’s operation ceased in 1905, with mail services discontinued after four years of serving the mining community. By 1906, Maxton remained operational, providing communication lifelines that made territorial isolation manageable for freedom-seeking prospectors.

The Senator Mine and Mining District

During the 1860s, prospectors staked claims in the Bradshaw Mountains near Hassayampa Creek, establishing what would become one of Arizona’s most significant mining operations.

By 1875, E.G. Peck, C.C. Bean, William Cole, and T.M. Alexander were actively working nearby deposits.

Historical maps show the Senator Mine‘s four parallel veins—Senator, Snoozer, Ten Spot, and Tredwell—striking northeast across wagon roads near Mount Union pass at 7,000 feet elevation.

You’ll find the Senator vein proved most profitable, yielding lead-zinc ores worth $530,000.

Mining techniques evolved from a short tunnel before 1871 to extensive operations featuring three miles of tunnels and an 835-foot-deep shaft.

The district operated a 20-stamp mill processing ore that initially assayed $85 per ton in gold, demonstrating the region’s mineral wealth.

The operation extracted ore as oxidation near surface, with free gold occurring alongside quartz in the primary veins.

Phelps Dodge acquired ownership of the mine after the 1890s, bringing additional capital and development to the operation.

Life as a Stage Stop and Supply Hub

Between Prescott and the Colorado River, Maxton emerged as the fourth and final night stop on the grueling journey from Buck Horn Station, establishing itself as a critical waypoint on the Prescott-Alexandria road. You’ll find its cultural significance rooted in serving teamsters and miners who depended on its general store for provisions before entering the mining districts.

The outpost featured a saloon where dust-caked travelers found respite, plus a post office established November 28, 1881. Transportation evolution transformed this remote desert halt into a boomtown of 3,500 residents by 1868, fueled by stage traffic connecting Prescott to Ehrenburg.

Mexicans, Colorado River Indians, and transient workers converged here, creating a diverse commercial hub where stagecoach networks sustained the settlement’s economic viability through constant movement of goods and people.

Smelter Operations and Peak Production Years

When construction commenced in December 1922, the Magma Copper Company initiated a $1.9 million project that would transform the town’s economic trajectory for decades.

The smelter’s 16-month construction timeline aligned with massive industrial infrastructure investments exceeding $4 million.

You’d witness the railroad’s operational upgrades from narrow to standard gauge, eliminating tight curves to accommodate oversized structural steel transport.

The Slow Fade Into Abandonment

You’ll find conflicting records about Maxton’s final years, with the post office officially closing in 1918 rather than 1905, though mining activity had already begun its irregular decline by the early 1900s.

The community’s economic pulse weakened considerably after ore quality diminished, forcing operations into sporadic bursts rather than sustained production.

Post Office Closure 1905

As the primary mining company backing Maxton declared bankruptcy in 1905, the town’s post office—established just seven years earlier during the community’s 400-person peak—closed its doors permanently. This infrastructure loss wasn’t merely administrative; it severed Maxton’s connection to outside commerce and communication networks essential for community development.

Unlike today’s artificial intelligence-driven logistics that might reroute services automatically, frontier mail systems depended entirely on economic viability. When mining operations ceased, the post office followed immediately—no revival attempts, no interim measures.

You’ll find this pattern repeated across Yavapai County’s ghost towns: the postal service closure accelerated resident exodus more effectively than any single event. Without mail delivery, isolated settlers couldn’t conduct business, maintain family connections, or access government services, making abandonment inevitable.

Sporadic Mining Until 1907

The post office’s 1905 closure marked Maxton’s administrative death, but the mines themselves limped forward for two more years in fits and starts. You’ll find mining decline documented through sporadic operations that yielded no sustained profits despite intermittent extraction attempts.

By 1907, the pattern mirrored other Yavapai ghost towns—unprofitable ore, isolation, and depleted veins forced final abandonment. The deepest shaft reached 600 feet by 1909, part of 15,000 feet of underground workings including drifts, stopes, and winzes that represented decades of effort.

No significant activity followed 1907’s cessation. Today, infrastructure remnants have vanished entirely, leaving minimal physical evidence of the camp’s existence.

This complete erasure typifies Arizona’s forgotten mining districts, where ambitious ventures dissolved into desert silence without trace.

What Remains Today and Visiting the Site

Today, Maxton exists primarily as a visible mine site along Senator Highway, south of Prescott in the Bradshaw Mountains. You’ll find preserved ore tracks leading into the mine entrance, though no ghost town architecture remains from the actual settlement.

Maxton survives as exposed mining infrastructure along Senator Highway, with ore tracks intact but settlement structures entirely vanished from the Bradshaw Mountains landscape.

The mining relics at Maxton represent the area’s most prominent features, easily accessible via back roads connecting other Bradshaw Mountain sites like Bueno and Goodwin.

When visiting, you can photograph the ruins from public areas, but you must respect no trespassing signs on private property. Never enter mine shafts—they’re prone to collapse and extremely dangerous.

Avoid touching soil or tailings near mining operations, and clean your hands and footwear afterward. Windblown dust may carry contaminants.

Senator Highway provides scenic access to these historical remnants.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Were the Original Prospectors That Staked the Senator Mine?

You’ll find prospector stories from the 1860s fade into legend, but records show the Senator Mine’s original stakers remain unnamed. Later mining techniques brought E.G. Peck, C.C. Bean, William Cole, and T.M. Alexander to these Bradshaw Mountain claims.

What Caused the Senator Mine to Play Out by 1893?

The Senator Mine exhausted its single profitable ore shoot by 1893 after extracting $530,000 worth. You’ll find limited mining technology couldn’t efficiently process remaining low-grade ores, while environmental impact from deeper extraction made operations economically unviable.

Were There Any Notable Incidents or Crimes During Maxton’s Operating Years?

No documented crimes occurred during Maxton’s operations, unlike other Arizona ghost town legends. You’ll find mining accident history surprisingly absent from records spanning 1883-1918, suggesting this Senator mine community maintained unusual peace despite typical frontier lawlessness elsewhere.

How Many People Lived in Maxton at Its Peak?

At its peak in 1925, you’d have found about 75 residents living in Maxton. This historic population decline began when mines played out, transforming it into one of Arizona’s ghost town attractions by the 1970s.

What Happened to Residents After the Post Office Closed in 1905?

Ever wonder where they vanished to? Unfortunately, you won’t find documented evidence of residents’ destinations after 1905. Today’s ghost town tourism and preservation efforts face challenges when primary sources simply don’t exist for abandoned settlements like this.

References

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/article/arizona-ghost-towns

- https://azgw.org/yavapai/ghosttowns.html

- http://www.apcrp.org/SENATOR_MAXTON/Lost_in_Plain_Sight.htm

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3FaJuF0N-XQ

- https://janmackellcollins.wordpress.com/category/senator-mine-arizona/

- http://bradshawmountains.com/mines.htm

- https://kellycodetectors.com/content/pdf/site_locator_books/AZ.pdf

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/maxton.html

- https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/1bf4aa8b-560b-467e-b691-a9a493ac8515

- https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/references/ReferenceViewer.aspx