You’ll find Mayo’s historic remains nestled in South Dakota’s Black Hills, where this late 1800s mining settlement once thrived during the region’s gold rush. The site features deteriorating foundations of its pioneer schoolhouse, built from cottonwood logs, and rusted playground equipment that hints at its vibrant past. While most structures have succumbed to time, Mayo’s story lives on through preservation efforts that chronicle the dramatic rise and fall of Black Hills mining communities.

Key Takeaways

- Mayo emerged as a mining settlement during the Black Hills gold rush of the late 1800s.

- The town featured a notable log schoolhouse that served as both an educational facility and community gathering space.

- Visible remains include schoolhouse foundations, weathered building remnants, and rusted playground equipment frames.

- Economic decline followed the typical boom-bust pattern of mining towns, influenced by water scarcity and shifting markets.

- Preservation efforts continue through historical societies, digital archiving, and collaboration with state preservation offices.

A Glimpse Into Mayo’s Past

While much of Mayo’s early history remains shrouded in mystery, this Black Hills settlement emerged during the region’s mining boom of the late 1800s.

You’ll find Mayo’s mining heritage reflected in the scattered remnants that still dot the landscape, telling ghost town stories of a once-bustling community.

Though exact founding dates haven’t survived in historical records, you can trace Mayo’s development through the familiar pattern of Black Hills settlements.

Like many Black Hills ghost towns, Mayo’s exact beginnings are lost to time, yet its story follows familiar pioneer patterns.

Like its neighbors, the town likely grew around mining operations, complete with the essential infrastructure of schools and basic services.

The schoolhouse, photographed standing in 1971, offers a rare glimpse into community life, suggesting Mayo experienced a gradual decline rather than a sudden abandonment.

Similar to Ardmore’s situation, the town faced challenges with lack of water that contributed to its eventual desertion.

Today, you’ll find Mayo among the 600-plus ghost towns that preserve the Black Hills’ pioneering spirit. These abandoned settlements provide valuable opportunities for aspiring photographers seeking unique locations amid empty buildings and natural surroundings.

Exploring the history of Melvin, South Dakota reveals a tale of resilience as early settlers navigated the challenges of frontier life. Each remnant of this once-thriving community tells a story, echoing the legacy of those who called it home. As visitors wander through its silent streets, they can almost hear the whispers of the past, bringing history to life amidst the tranquil landscape.

Life in a Black Hills Settlement

As settlers flooded into the Black Hills during the 1870s gold rush, Mayo’s residents faced daily challenges typical of frontier mining communities.

You’d have found yourself maneuvering a complex web of claim disputes and settler conflicts while trying to establish a life in this rugged terrain. The discovery of gold had drawn thousands to these sacred Lakota lands, despite the Fort Laramie Treaty’s protections of indigenous rights.

Life centered around the mines, with saloons and dance halls serving as community hubs where you could escape the day’s toils. The government’s sell or starve policy forced many Sioux off their ancestral lands, leading to heightened tensions in the region.

The dark, dense forests of ponderosa pine covered the surrounding hillsides, giving the mountains their characteristic shadowy appearance.

You’d have witnessed the strain between settlers and Native Americans intensify as mining operations expanded, disrupting traditional hunting grounds.

The boom-bust nature of mining towns meant you couldn’t count on long-term stability – fortunes rose and fell with each new gold strike.

The Schoolhouse Legacy

You’ll find Mayo’s schoolhouse stood as one of Dakota Territory’s pioneering educational outposts, following the establishment of the territory’s first permanent school near Vermillion in 1860.

The school’s weathered grounds once echoed with children’s laughter and games during South Dakota’s early settlement period, serving as both classroom and community gathering space. Similar to Emma Bradford’s historic role, cottonwood log construction defined these early frontier schools. Like Vermillion’s first schoolhouse, it served as a hub for multiple community functions, including religious services and political meetings.

Through preservation efforts led by the Log School House Association in 1909, including a monument on Ravine Hill and later reconstruction projects, Mayo’s schoolhouse remains a tribute to the region’s commitment to rural education.

Rural Education Pioneer

When South Dakota’s rural landscape first bloomed with one-room schoolhouses in the early 1900s, these humble wooden structures became pioneers of frontier education.

You’ll find their impact went far beyond basic academics, as they served as the backbone of rural education and community development across the state.

These pioneering institutions shaped frontier life through:

- Multi-grade classrooms where a single teacher managed all subjects and ages

- Community gatherings for box socials, spelling bees, and holiday celebrations

- Peak numbers reaching 5,519 schools in 1919, serving dispersed settlements

- Average class sizes of just 10 students, ensuring personalized attention

Though many schools closed during the Great Depression, with enrollments dropping 55% by 1945, their legacy endures in the 300+ preserved structures across southeastern South Dakota’s counties.

The Country School Legacy project helped document and preserve the rich history of these rural schools through photographs, oral histories, and traveling exhibits from 1980-1981.

Playground Through Time

Standing quietly in rural Mayo, South Dakota, a humble schoolyard once echoed with children’s laughter and games until 1971.

You’d have found a simple, utilitarian playground space that served both educational and social purposes for the scattered farming families in the area. The playground’s evolution mirrored the community’s modest means – likely featuring an open field where children played traditional games during recess and lunch breaks. Custer County records show this school was one of many rural educational outposts in the region.

Beyond school hours, you’d have seen the playground transform into a gathering spot for community events, town meetings, and social functions. Today, visitors can share their photos of the historic grounds through social media platforms, preserving its memory for future generations.

While no detailed records exist of the playground’s specific features, it represented the heart of rural life where children learned, played, and grew together until changing times led to the school’s closure.

Last Class Standing

Every rural schoolhouse tells a story, and Mayo’s final class of 1971 marked the end of an era that shaped South Dakota’s educational landscape.

You’ll find echoes of cherished school traditions in the weathered walls that once witnessed countless community gatherings and children’s laughter.

The legacy of Mayo’s schoolhouse lives on through:

- Historical records and photographs preserved through the Country School Legacy project

- Oral histories from former students who shared their memories of daily lessons

- Cultural artifacts that reflect the architectural style brought by Eastern settlers

- Community-driven preservation efforts that protect these symbols of rural education

Like many rural schools across South Dakota, Mayo’s schoolhouse stood as a testament to the region’s commitment to education, even as changing times led to its eventual closure.

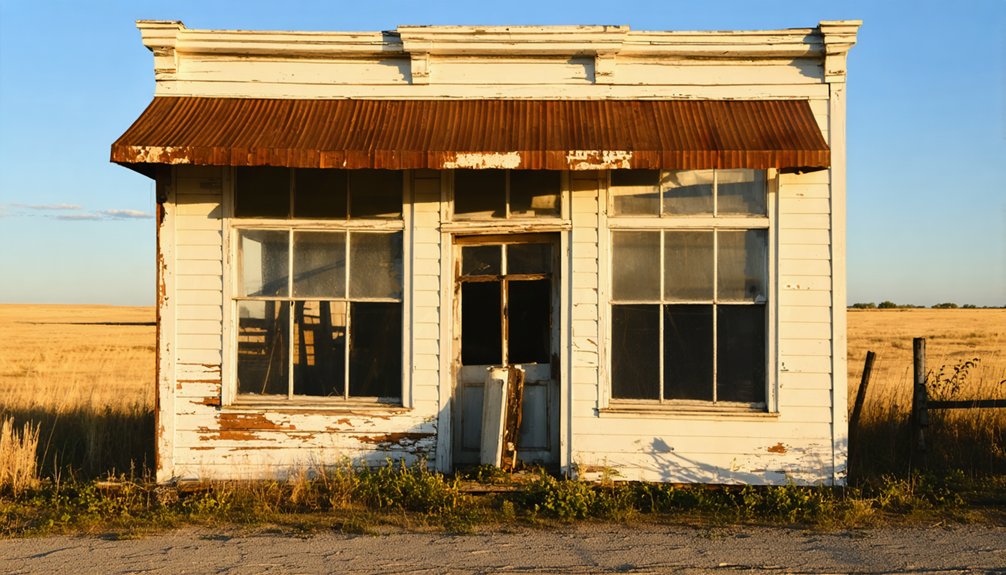

Architectural Remains Today

You’ll find Mayo’s original schoolhouse foundations still visible among the prairie grass, though the wooden structure itself has largely collapsed into weathered remnants.

A few rusted playground equipment pieces remain nearby, including the metal frame of an old swing set and fragments of what was likely a slide or climbing structure. Like many Black Hills ghost towns, Mayo’s remnants require patient exploration to uncover traces of its past community life.

The scattered architectural elements around the school site offer glimpses into daily life during Mayo’s active years, with visible features like the flagpole base and remnants of a coal shed still marking the property’s educational heritage.

School Building Features

The weathered remains of Mayo’s one-room schoolhouse reveal the architectural character of late 19th-century rural education in South Dakota.

You’ll find a structure that exemplifies pioneer educational architecture, with its wood-frame construction and large windows designed to maximize natural lighting for students. The historical significance of this building is evident in its traditional features, though deterioration has claimed much of its original character.

Key elements that defined Mayo’s schoolhouse include:

- A distinctive bell tower used for signaling school times

- Post-and-beam construction typical of homesteader craftsmanship

- Spacious window openings that dominated the facade

- A utilitarian layout featuring a principal’s office and library space

The building’s current state, marked by roof bowing and structural instability, tells the story of Mayo’s decline and abandonment.

Playground Equipment Status

Modern exploration of Mayo reveals little evidence of playground equipment, with no documented remains of swings, slides, or climbing structures at the former school site.

The playground evolution in Mayo follows a typical ghost town pattern, where recreational structures deteriorate rapidly without maintenance and eventually vanish from the landscape.

If you’re exploring Mayo’s ghost town remnants today, you won’t find intact playground equipment. Like many rural South Dakota communities, Mayo likely had minimal manufactured play structures to begin with, possibly relying on natural play areas instead.

Any equipment that did exist has likely been removed by authorities for safety reasons or succumbed to decades of exposure.

Historical photographs and recent documentation focus on building ruins and foundations, suggesting playground features weren’t substantial enough to leave lasting traces.

Mayo’s Economic Rise and Fall

During its formative years, Mayo’s economic trajectory mirrored the broader patterns of South Dakota’s development, beginning with the fur trade era‘s bustling activity along the Missouri River.

The community’s economic shifts paralleled the region’s evolution from trade post to agricultural center, reflecting the dynamic changes in community dynamics.

Mayo’s rise and eventual decline followed these key developments:

- Initial prosperity from steamboat trade and early settlement activity

- Agricultural boom with the arrival of railroads and implementation of mechanized farming

- Brief period of growth during the regional wheat farming expansion

- Eventual decline as rail routes bypassed the town and agricultural markets shifted

You’ll find that Mayo’s story exemplifies how transportation access and changing agricultural patterns determined the fate of many small Dakota communities.

Documenting a Lost Community

Despite extensive research efforts, documenting Mayo’s history presents significant challenges due to limited surviving records and physical evidence.

You’ll find Mayo’s most concrete mention in the Watson Parker Ghost Town Notebooks at Black Hills State University’s Case Library, offering a rare glimpse into this vanished settlement.

The community’s connections emerge primarily through school records from 1971, suggesting Mayo sustained enough population to maintain educational services longer than many Black Hills ghost towns.

While you won’t find detailed maps or photographs in public archives, Mayo’s presence in specialized collections confirms its role in South Dakota’s past.

The settlement’s gradual fade from memory, rather than dramatic collapse, leaves researchers piecing together fragments from academic collections to reconstruct its story.

Preserving Mayo’s Memory

Through dedicated community-led initiatives, Mayo’s legacy endures as local historical societies and preservation groups work to safeguard what remains of this Black Hills ghost town.

Community engagement drives preservation efforts through annual commemorative walks, clean-up days, and educational programs that connect younger generations to Mayo’s past.

Historical preservation strategies include:

- Digital archiving of photographs, maps, and documents

- Recording oral histories from descendants of former residents

- Utilizing state preservation grants and tax incentives

- Implementing GIS mapping to document site changes

You’ll find Mayo’s story being kept alive through the South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office programs and during Archaeology and Historic Preservation Month celebrations each May.

These efforts guarantee that this piece of Black Hills history won’t fade into obscurity.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Families Who Last Lived in Mayo?

You’ll find most Mayo families moved to bigger towns like Rapid City for jobs, while Mayo descendants spread across South Dakota and Wyoming. Some kept their land but nobody lives there permanently.

Are There Any Burial Grounds or Cemeteries Near Mayo?

While you might expect clear records, the burial history near Mayo remains mysterious. You’ll find scattered informal burial grounds in the region, but no officially documented cemetery of historical significance.

Was Mayo Connected to Any Native American Settlements or Trading Routes?

You’ll find that Mayo likely connected to Native American trading routes, as it sat within Sioux territory where established networks linked Northern Plains tribes along waterways and traditional pathways throughout the region.

Did Mayo Have a Post Office During Its Active Years?

You won’t find evidence of a post office in Mayo’s history, as historical postal records don’t list one. Your mail would’ve likely been handled through nearby established post office operations in Edmunds County.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness Reported in Mayo?

Like a blank page in history’s book, you won’t find any documented crime history or law enforcement issues in Mayo’s records. No notable lawlessness has been discovered in historical accounts.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Glucs_Rq8Xs

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0WNYsFLSLA

- https://www.sdpb.org/rural-life-and-history/2023-08-21/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins

- https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-2-2/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins/vol-02-no-2-some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins.pdf

- https://www.blackhillsbadlands.com/blog/post/old-west-legends-mines-ghost-towns-route-reimagined/

- https://icatchshadows.com/okaton-and-cottonwood-a-photographic-visit-to-two-south-dakota-ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_South_Dakota

- https://b1027.com/south-dakota-has-an-abundance-of-ghost-towns/

- https://explore.digitalsd.org/digital/collection/WPGhosttown/id/4605

- https://www.powderhouselodge.com/black-hills-attractions/fun-attractions/ghost-towns-of-western-south-dakota/