Michigan entered statehood on January 26, 1837. It was the 26th state to join the United States of America.

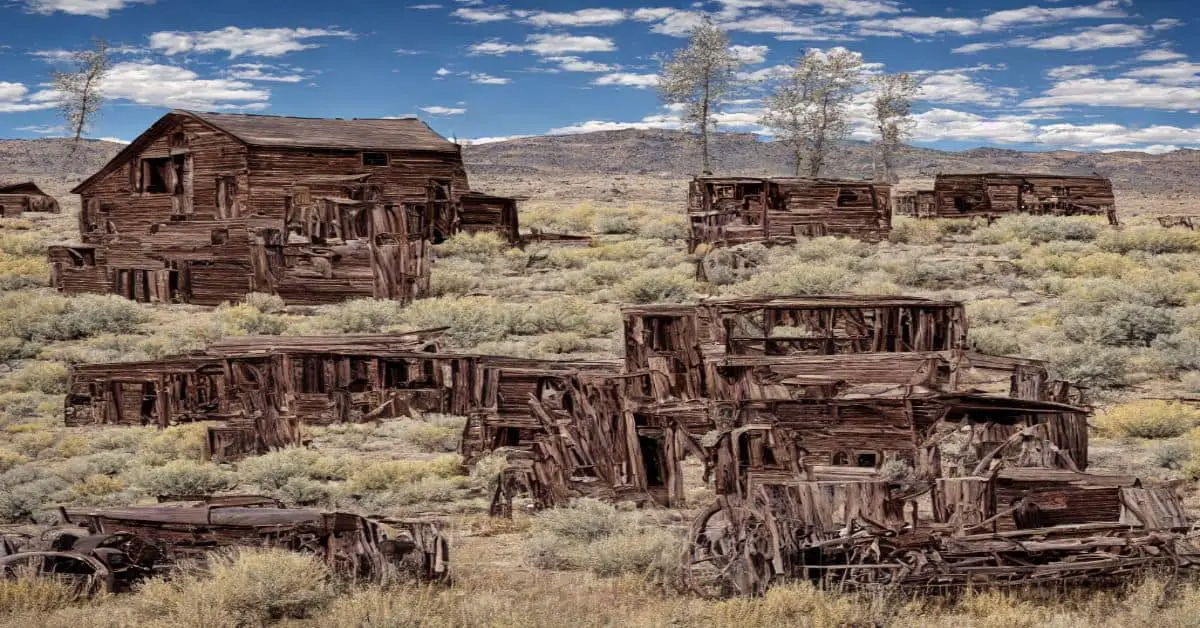

There are an estimated 134 ghost towns in Michigan. The list of ghost towns is unfinished as information is still being gathered on the state and towns that created it. As more knowledge is gained, the list may continue to grow.

Even before joining the other twenty-five states, Michigan had communities, settlements, and villages. The oldest town in Michigan is Sault Ste. Marie was founded in 1668 by French missionaries. Not only is this the oldest town in Michigan, but it is also the third oldest town in the United States.

Fayette, Michigan

Located on the Big Bay de Noc is the historic ghost town of Fayette, Michigan. Fayette is now part of the Fayette Historic National Park, but the town was an industrial community known for manufacturing charcoal pig iron during its prime days. Visiting the national park will offer an opportunity to travel back in time and see what life was like in the late 1800s as visitors walk through Fayette’s living museum.

In 1867, Fayette Brown, an agent of Jackson Iron company, chose the Upper Peninsula site to establish an iron-smelting operation. To honor the founder, the town was named Fayette. Over the next twenty-four years, the town would be home to roughly 500 residents, including locals and those who traveled from Canada, northern Europe, and the British Isles to work the iron factories.

The town’s two blast furnaces produced 229,288 tons of iron from 1867-1891. Iron was in high demand after the Civil War, and Fayette was one of the top iron producers. Once the need for iron declined and Fayette’s purifying resources ran low, the Jackson Iron Company shut down and ceased all iron-smelting operations.

From 1891-1916, Fayette’s area was transformed into a resort and fishing village, utilizing the large dock and easily accessible fishing waters of Lake Michigan. In 1916, the town was purchased and turned into a summer resort until 1946, when it was sold to another individual.

The Escanaba Paper Company was the last owner of the land before being negotiated with the Michigan government and becoming part of the state park in 1959. On February 16, 1970, Fayette was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

There are approximately 61 campsites in the park and boat camping in Snail Shell Harbor. The state park has around 5 miles of hiking trails. Spider Cave can also be found within the park above the base of Burnt Bluff.

Over 20 buildings in the Fayette township have been restored and are open for walk-through experiences of the past. The best time to visit Fayette is May through March, while weather conditions are optimal.

Kensington, Michigan

Kensington, Michigan, was first settled in 1831 in present-day Oakland County within the Lyon Township. On June 9, 1834, a post office was opened. Just twenty years later, by 1854, Kensington had a population of over 300 residents.

While Kensington was still growing and building throughout the 1840s and 1850s, it was unknowingly falling apart simultaneously. A national banking crisis that started in 1837 found Kensington in 1839. The local bank continued to print more money than it had in the vault to back the currency.

In the fall of 1839, after the harvest season replenished the bank’s empty vault, two of the bank’s coffers, Dwight and Dix, took the money and disappeared to Milwaukee, where they bought jewelry, land, and livestock. It has been debated whether the men took the money with ill intentions or took it as an act of desperation to save the bank with newly purchased assets.

After state laws were passed in Michigan requiring banks to show real estate security, all but two men recorded land titles in their wives’ names to avoid the new law. The two men who left titles in their own names issued a reward for Dwight and Dix’s return, who had left Kensington.

The two were arrested in Wisconsin, and most of Kensington’s money was recovered, but the bank of Kensington was forced to close due to a lack of assets.

After another bill was passed, the Wholesalers Act, merchants and villagers stopped paying their bills and left town without notifying their creditors. When eastern investors went to Kensington to collect debts, a large portion of the population left, leaving empty homes, stores, and other buildings.

Any banknote that was created at the Kensington Bank became worthless. Today, Kensington Banknotes are seen as prized materials and collectibles that are often exchanged for more than their fair price value.

In 1871, the Detroit, Lansing, and Lake Michigan Railroad was built to provide transportation from Detroit to Lansing. While the railroad had a beneficial objective, it was merely another part of the chain reaction that ultimately ended Kensington as a community.

After a second significant population loss from the Detroit to Lansing railroad in 1871, a second railroad was established in 1882, the Michigan Air Line Railroad.

By 1905, the Kensington Post Office was closed, and only four families remained in the town. In the 1950s, what remained of Kensington was demolished and leveled to make way for the Kensington Metropark and I-96.

The Kensington Cemetery, some relics, and a few foundations throughout the Kensington Nature Center and Metropark trail are all that remain of Kensington.

Rawsonville, Michigan

Rawsonville, Michigan, started as Snow Landing in 1800 when Henry Snow first settled the area. In 1825, Ambline Rawson and Amasah Rawson claimed residence in the small village. On January 7, 1836, Amasah and two others filed a community plat as Michigan City.

In 1838 there was another name change from Michigan City to Rawsonville. November 14, 1838, The Van Buren post office was moved from the Van Buren Charter Township to Rawsonville and changed its name accordingly.

During the Civil War, Rawsonville had a grist mill, sawmill, stove factory, and wagon maker. The community was doing well, but when a railroad was built that bypassed the town, it took a toll on the industries and families. The post office closed on October 25, 1895, and reopened on November 20, 1895, but saw the final closure a few years later, on February 28, 1902.

In 1900, few residents remained in the village, and in 1925, the Eastern Michigan Edison Company built the French Landing Dam and Powerhouse on the Huron River. Rawsonville was flooded, and most of the once village now rests under the water of Belleville Lake.

The former village was dedicated as a Michigan State Historic Site on October 27, 1983. Today, only a sign with a brief history of the village is left to mark where the town once was.

Ghost Towns And Other Abandoned Locations Worth Seeing In Michigan

Central, Michigan, is located on the Upper Peninsula and once had 1,300 residents consisting of locals, German, and Cornish immigrants that worked in the copper mines. The town had one of the first telephone services of Copper County, a post office, and a three-story school.

The copper mine opened in the 1850s and closed in 1898. Once the mine closed, residents abandoned the town to find work at other mines and mining towns. All that remains of the town are thirteen houses and a Methodist church that the Keweenaw Historical Society maintains.

Pere Cheney, Michigan, was a turn-of-the-century lumber town. At the town’s peak, the population was around 1,500 residents, but sadly many were killed from back-to-back diphtheria epidemics. By the 1920s, the town was abandoned and rumored to be haunted by the locals’ ghosts. The cemetery remains with gravestones showing how quickly and unfortunately, lives can be lost.

Finn Town, Michigan, was a copper mining town that served the Victoria Copper Mine on the Upper Peninsula. Ghost town enthusiasts and visitors alike can explore the remains of log cabins still on their original foundations that once housed miners’ families.

Nonesuch, Michigan, was established as a copper mining town, but the copper vein presented quite a challenge for miners to extract. Due to the copper vein’s complexities, the site was named “the Sphinx of the copper district.” The town’s largest population was only a few hundred residents, but there were a post office, school, cabins, and other buildings. Ruins of Nonesuch remains can be found throughout the woods along the Porcupine Mountains’ Nonesuch Trail and past Nonesuch Falls.

Singapore, Michigan, started as a great idea but eventually fell victim to natural causes. Being next to Lake Michigan, Singapore’s town was planned to be one of the major port towns that rivaled Chicago and Milwaukee.

Not knowing what would happen at the time, as the area was deforested to rebuild Chicago and Holland after the fires of the 1800s, the port town was now exposed to wind and sand erosion and suffered from natural occurrences. By 1875 most Singapore residents left, with the remaining going not long after the town was witnessed to be buried under the sand.

Shining light over Lake Superior’s waters for forty years, The Grand Island East Channel Lighthouse now sits as an abandoned building. The lighthouse was first operational in 1868 and retired 40 years later in the early 1900s. The best way to view the wooden lighthouse is by kayak or boat.

The Belle Isle Zoo in Detroit, Michigan, is an eerie scene. Starting as the outdoor Belle Isle Zoo and later the Children’s Zoo, the location was open for 107 years before being shut down in 2002. The goal was to save $700,000 by shutting down Belle Isle Zoo and opening a new Michigan-themed Nature Zoo. When the island became a state park in 2013, rumors of significant changes happened with the Belle Isle Zoo.

Similar to a zoo, Ann Arbor has a prehistoric forest amusement park. The park consists of fiberglass dinosaurs that once were the main roadside attraction from 1963 until 1999. There were rumors of current owners reopening the park and bringing the prehistoric creatures back to life. If you are in the area, this could be one of the best or eeriest stops.

Among other locations listed as the most haunted places in the Holy Family Orphanage, built in 1915 and closed in 1965. The building once housed 200 children, including refugees from Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Multiple classrooms, dormitories, playrooms, a dining hall, and other property facilities exist.

Urban legends tell of the mistreatment and demise of children that resided in the house throughout the years. The property has been under renovation since 2016, with plans to reopen as a modern-themed apartment building.