You won’t find much information about Minear, a remote California ghost town that emerged in the early 20th century during the Sierra Nevada gold rush. This mining outpost thrived briefly with rich gold, silver, and lead deposits before its eventual abandonment. Today, its deteriorating structures—collapsed worker quarters and rusted equipment—require high-clearance vehicles to access via unmarked dirt roads. With no formal protection, Minear’s historical significance faces an uncertain future as time continues its relentless march.

Key Takeaways

- Minear emerged as a mining outpost in California’s Sierra Nevada region during the Gold Rush era of the early 20th century.

- The town experienced typical boom-town development with diverse miners from America, Europe, and China creating a complex social fabric.

- Mining operations evolved from basic panning to advanced extraction methods with deep shafts exceeding 3,000 feet by early 1900s.

- Rich deposits of gold, silver, and lead supported the thriving community before gradual decline following resource depletion.

- Today, Minear remains remote with deteriorating structures, requiring high-clearance vehicles for access and lacking formal preservation protection.

The Lost Mining Settlement of Minear

Tucked away in California’s Sierra Nevada region, Minear emerged as one of many hopeful mining settlements during the Gold Rush era.

Like its neighboring camps, Minear’s history began with placer mining operations along local waterways, where prospectors sifted through gravels for surface gold deposits.

As easy pickings diminished, miners turned to drift mining, tunneling into hillsides following gold-bearing quartz veins. This shift reflected the broader evolution of California’s mining industry from individual prospectors to organized operations requiring significant capital investment.

Minear’s cultural impact mirrored the ethnic diversity common in Sierra mining camps, with a mix of American, European, and Chinese miners creating a complex social fabric. By 1849, these mining communities were filled with forty-niners who had traveled thousands of miles in search of fortune.

Despite tensions over resources and mining claims, these settlements established rudimentary governance systems that would influence California’s developing identity. Like many California mining towns, Minear faced the constant threat of becoming a ghost town once its precious metals were depleted.

Historical Timeline and Development

While the Sierra Nevada region hosted numerous Gold Rush settlements in the mid-1800s, Minear’s story actually began much later in the early 20th century as a Mojave Desert mining outpost.

The settlement patterns followed typical boom-town development, with infrastructure rapidly expanding to support incoming prospectors seeking fortune in the hills.

Infrastructure mushroomed as fortune-seekers flooded into the hills, following the classic boom-town blueprint.

You’ll find Minear’s trajectory followed a predictable arc: rapid population growth during active mining years, then gradual decline as ore deposits depleted, much like how Old Shasta Town experienced prosperity followed by economic decline when business moved to nearby Redding.

Community dynamics centered around essential services—post office, general store, saloon, and schoolhouse—creating a functional if isolated society. Similar to nearby settlements like Halloran Springs, Minear likely saw mining activities commence around 1902 when gold mining first gained traction in that area.

Mining Operations and Mineral Wealth

Minear’s mines primarily yielded gold-bearing quartz veins that required hard-rock extraction methods, evolving from early placer operations to more sophisticated drift mining techniques by the 1860s.

You’ll find that miners initially used basic panning and sluicing operations before implementing stamp mills and mercury amalgamation processes to increase yields during the settlement’s peak production years of 1870-1885.

The area’s declining output coincided with depleted surface deposits, forcing mining companies to dig increasingly deeper shafts at prohibitive costs until operations ceased entirely. Much like the historic Kennedy Mine which reached 5,912 feet in depth, these operations faced significant challenges as they ventured deeper underground. Similar to the Mount Diablo Coalfield, Minear experienced a significant economic shift when coal mining ended and residents had to transition to other industries or abandon the settlement.

Mineral Composition Analysis

The rich mineral deposits of Minear contributed greatly to its rise as a mining boomtown before eventually becoming a ghost town.

Like other California ghost town geology sites, Minear’s landscape held valuable mineral significance, primarily silver and lead, with ore assays reaching impressive concentrations of 80-90 ounces per ton similar to Castle Dome’s yields.

You’ll find that Minear followed the pattern of many mining districts, where high-grade silver attracted initial settlement, while lead served as a profitable secondary mineral. The town experienced a rapid population growth and decline similar to Eagle Mountain, which housed nearly 4,000 residents during its operational years. The abundance of these minerals created a boom-bust cycle similar to Bodie, California, where mining operations expanded rapidly before declining when resources thinned out.

As surface deposits depleted, miners pursued deeper veins, eventually discovering zinc deposits similar to those in Cerro Gordo that sparked a secondary boom in the early 1900s.

The combination of these minerals created enough economic impact to briefly support a thriving community before the inevitable decline.

Extraction Techniques Used

Mining operations in Minear evolved from simple surface extraction to sophisticated underground methods as the town’s mineral wealth demanded more advanced techniques.

You’d find miners utilizing vertical shafts that reached depths exceeding 3,000 feet by the early 1900s, accessing rich quartz veins previously thought unreachable.

The extraction methods progressed dramatically with horizontal tunnels (drifts) extending over 7,900 feet by 1874.

These underground techniques required innovative water management systems—giant pumps removed water continuously, allowing mining below the previously assumed 1,200-foot limit.

By 1899, mules were working underground to haul ore through the extensive tunnel networks.

Hard-rock mining replaced placer extraction, necessitating blasting and crushing of quartz to liberate gold particles.

The introduction of cyanide leaching method in 1905 significantly improved the efficiency of gold extraction from processed ore.

Processing plants were regularly modernized to handle ore from increasing depths.

The transition from hand drills to power drills in the mines occurred around 1868, dramatically increasing productivity with dynamite adoption transforming blasting operations.

Peak Production Years

While California’s gold rush reached its zenith between 1848 and 1855, Minear experienced its most productive mining period slightly later, from 1850 to 1880, as operations shifted from simple placer mining to sophisticated hard-rock extraction.

During these peak years, you’d have witnessed Minear’s transformation as the minear gold industry flourished alongside rapid urbanization and infrastructure development.

By 1860, easily accessible placer deposits were largely exhausted, prompting local companies to invest in underground mining operations that sustained production well into the late 19th century.

This mining legacy yielded significant wealth—contributing to California’s impressive 12 million ounces of gold extracted in the early rush years.

However, declining gold prices and the 1884 ban on hydraulic mining marked the beginning of Minear’s gradual decline, though some operations persisted on a smaller scale into the early 20th century.

Abandoned Structures and Artifacts

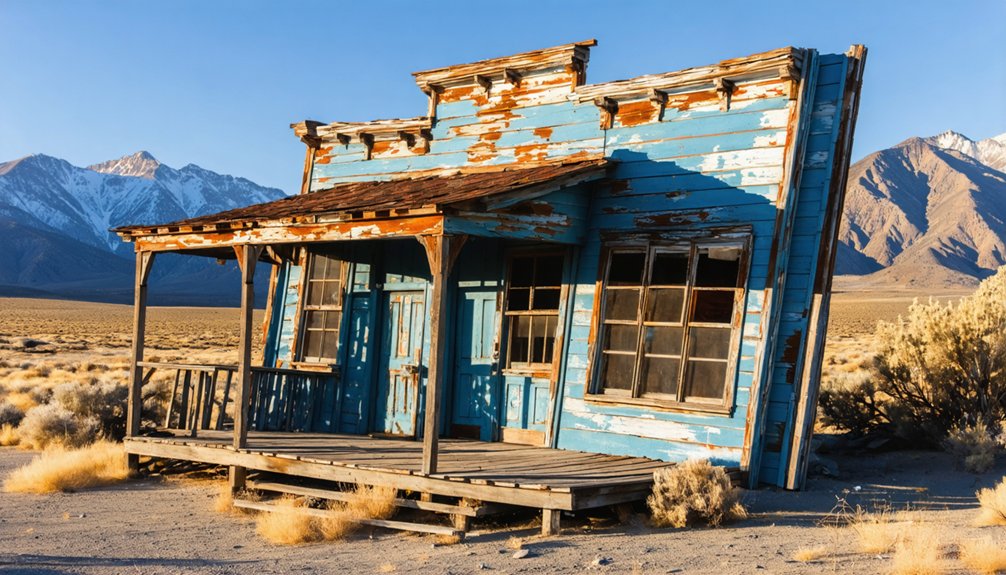

As you walk through Minear’s abandoned mining district, you’ll encounter the remains of worker quarters where timber frames sag against the harsh California elements.

A trail of rusted equipment marks the path between former operational areas, with ore carts and pulley systems now frozen in their final positions.

These deteriorating structures offer archaeologists valuable insights into the mining technologies and living conditions of the late 19th century boom period.

Dilapidated Mining Quarters

The dilapidated mining quarters stand as silent witnesses to Minear’s abrupt abandonment when operations ceased in the early 20th century.

These weathered structures reveal the harsh reality of miners’ lives, with their simple wooden frames now yielding to decades of desert exposure.

You’ll find several bunkhouses arranged in rows, designed to house up to 40 workers each.

The foreman’s quarters, slightly larger and positioned at the hillside’s edge, offered marginally better accommodations.

Inside these abandoned buildings, rusted bed frames and broken chairs remain frozen in time.

Mining relics scattered throughout include personal effects—tin cups, work boots, and leather gloves—suggesting workers left in haste.

The mess hall’s collapsed roof and kitchen area, with dishes still stacked, further emphasize the town’s sudden desertion.

Rusted Equipment Trail

Rusted remnants of Minear’s mining industry litter the winding trail that cuts through the ghost town‘s perimeter, telling a story of technological ambition defeated by time and elements.

You’ll encounter ore carts still positioned on rail tracks, alongside stamp mills and primitive arrastras that once pulverized precious minerals.

The equipment’s historical significance becomes apparent as you notice:

- Welded metal fragments and maintenance tools, indicating on-site repairs

- Massive machinery pieces that required disassembly and mule transport

- Depression-era structures repurposed by the Civilian Conservation Corps

Nearby crumbled stone foundations mark where assay offices and bunkhouses once stood.

While equipment restoration efforts face challenges from harsh desert conditions and difficult access, these corroded artifacts preserve a tangible connection to California’s industrial past, standing defiant against wilderness reclamation.

Accessing the Ghost Town Today

Reaching Minear ghost town today presents significant challenges due to its remote location in Mariposa County.

The site lacks established access routes, requiring visitors to navigate rural dirt roads that likely demand high-clearance vehicles. During wet conditions, 4WD becomes essential for traversing the hilly terrain typical of California gold country.

Before attempting the journey, you’ll need to research land ownership status and potential restrictions, as no documented public access information exists specifically for Minear.

Prepare your vehicle thoroughly and bring extra supplies—there are no amenities, potable water, or maintained trails at the site.

GPS coordinates from historic registries can guide your approach, but expect to travel without clear signage.

Remember to share your itinerary with others, as emergency communication may be limited in this isolated area.

Comparing Minear to Other California Ghost Towns

While Minear stands as a lesser-known footnote in California’s mining history, it shares many characteristics with the state’s more prominent ghost towns like Bodie, Calico, and Cerro Gordo.

Though obscure in California’s mining narrative, Minear embodies the classic ghost town story shared by its famous counterparts.

These ghost town characteristics typically follow a pattern of boom-and-bust economics tied to mineral depletion.

In comparing Minear to its counterparts, you’ll notice three key similarities:

- Economic trajectory – like Bodie’s $38 million gold production and Calico’s $20 million silver boom, these towns rose and fell with their resources.

- Population volatility – rapid growth followed by mass exodus when minerals disappeared.

- Geographic isolation – harsh environmental conditions that initially challenged mining operations and later preservation efforts.

Unlike Calico (now a tourist attraction) and Bodie (a state park), Minear’s preservation status remains less established, making it representative of California’s more authentic abandoned settlements.

Preservation Status and Future Outlook

The preservation status of Minear differs substantially from California’s better-protected ghost towns. Unlike Bodie, which enjoys designation as a State Historic Park and National Historic Landmark with its “arrested decay” approach, Minear lacks formal legal protection and dedicated conservation funding.

You’ll find no regulated maintenance or prohibition against artifact removal at Minear. Without state oversight, preservation challenges include accelerated deterioration, potential vandalism, and the absence of structural monitoring systems.

The remaining buildings face environmental threats without intervention strategies. Future strategies for Minear’s survival depend on grassroots advocacy efforts to secure historical designation and protection status.

Without legal safeguards similar to those established for Bodie in 1962, Minear’s physical remnants will likely continue to disappear, leaving only historical records as evidence of its mining-era existence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Outlaws Associated With Minear?

Under the dusty California sun, you’d find no documented Minear outlaws. Historical records don’t reveal any notable Minear crime incidents, unlike larger ghost towns that gained notoriety for their criminal elements.

What Happened to the Residents After Minear Was Abandoned?

After Minear’s closure, you’d have seen residents scatter to nearby towns and cities seeking jobs. This mass migration emptied the town by the 1930s, severing community bonds in the process.

Are There Any Ghost Stories or Paranormal Claims About Minear?

You won’t find documented ghost sightings or paranormal investigations in Minear. Unlike popular California ghost towns that attract supernatural interest, no specific paranormal claims exist for this lesser-known desert settlement.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Visit or Live in Minear?

Based on available historical records, you won’t find evidence of any famous visitors or historical figures living in Minear. Its historical significance remains undocumented compared to more prominent California ghost towns.

Is Metal Detecting or Artifact Collection Permitted at Minear?

Metal detecting isn’t prohibited, but you’re restricted by regulations limiting surface searching only. You can’t collect artifacts over 100 years old, as artifact collection ethics and federal law prohibit removing historical items.

References

- https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/historyculture/death-valley-ghost-towns.htm

- https://parks.sbcounty.gov/opinion-beyers-byways-a-brief-history-of-calico-ghost-town/

- https://dornsife.usc.edu/magazine/echoes-in-the-dust/

- https://www.visitcalifornia.com/road-trips/ghost-towns/

- https://www.islands.com/1878743/one-lagest-ghost-towns-eerily-modern-abandoned-california-mining-town-eagle-mountain/

- https://capitolmuseum.ca.gov/state-symbols/silver-rush-ghost-town-calico/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerro_Gordo_Mines

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpOYp-7d2A0

- https://www.visitmammoth.com/blogs/history-and-geology-bodie-ghost-town/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/state/california/