You’ll find Morrisonville’s ghostly remnants behind Dow Chemical’s security gates in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, where only a historic cemetery and prayer grounds remain. Founded by freed slaves in the 1870s near Plaquemine, this once-thriving Black settlement flourished along the Mississippi River until 1989, when chemical contamination forced a $7 million community buyout. The story of Morrisonville reveals deeper truths about environmental racism and corporate displacement in America’s industrial corridors.

Key Takeaways

- Morrisonville was an African American community established in the 1870s near Plaquemine, Louisiana by freed slaves seeking independence.

- Dow Chemical’s vinyl chloride plant operations in 1958 transformed the area into a contaminated zone, forcing residents to abandon their homes.

- A $7 million buyout by Dow Chemical in 1989 led to complete community displacement, leaving only cemeteries and a prayer site.

- The settlement became part of “Cancer Alley,” with residents experiencing severe health issues from industrial contamination before relocation.

- Today, Morrisonville exists only through preserved memories, photographs, and annual gatherings of former residents, with restricted access to remaining sites.

The Founding of a Free Community (1870s)

During the tumultuous period following the Civil War, Morrisonville emerged as a symbol of African American resilience when a group of newly freed slaves established their own community in the 1870s near Plaquemine, Louisiana.

The founding principles of Morrisonville centered on self-determination and independence, as former plantation workers chose this location for its strategic advantages. In 1889, the community was formally established when Rev. Robert Morrison founded the settlement.

Former slaves established Morrisonville with a vision of autonomy, strategically selecting their community’s location to ensure lasting independence.

You’ll find that they selected land near crucial waterways, ensuring access to resources and transportation. The settlement’s prime location along the Mississippi River banks provided vital access for trade and sustenance.

The cultural foundations of this mainly African American settlement were built on strong family bonds and shared agricultural expertise.

The community’s members worked together to construct homes and essential buildings, creating a self-sustaining haven where they could preserve their traditions and cultural heritage, despite the economic challenges that faced newly emancipated people during this era.

Life Along the Mississippi River

While the Mississippi River shaped life in countless riverside communities, its influence on Morrisonville proved particularly significant.

You’d find residents adapting to the river’s seasonal rhythms, with spring thaws and heavy rains determining their daily activities. The mighty waterway, flowing at 470,000 cubic feet per second, supported traditional river traditions like fishing practices that sustained families and local trade. Early Native American tribes like the Quinipissa tribe once inhabited these fertile lands before European exploration changed the landscape forever. The rich soil of the river’s 30 million acre floodplain made agriculture the backbone of the local economy.

Before bridges connected the shores, ferries transported people and goods across the 45-foot shipping channel, making Morrisonville an essential part of river commerce.

The community’s connection to the water ran deep, from the early days of plantation agriculture to later industrial developments. Yet this relationship wasn’t without challenges – residents faced recurring displacement from levee construction and industrial expansion, forcing them to repeatedly rebuild their lives along the river’s banks.

From Australia Point to Graceville

You’ll find Australia Point’s original riverside location was strategically chosen by formerly enslaved people in the 1870s, offering essential access to the Mississippi River’s resources.

The settlement’s position along the river provided residents with transportation routes, fertile soil for farming, and economic opportunities through river trade.

Your understanding of this early community wouldn’t be complete without noting how the Mississippi River shaped both daily life and commerce, though these same waters would later force the town’s first relocation to Graceville.

Like the residents of historically black communities throughout Louisiana, these early settlers built close-knit neighborhoods centered around family-owned businesses and shared cultural ties.

Similar to the story of Black landowners in Mossville founded in 1790, these communities demonstrated remarkable self-governance and resilience despite societal obstacles.

Early Settlement Location

After gaining their freedom in the 1870s, formerly enslaved African Americans established Morrisonville near Australia Point, a fertile stretch along the Mississippi River near Plaquemine, Louisiana.

The settlement dynamics favored this location for its elevated terrain, which provided natural protection from the flooding that often plagued surrounding bayous. Like the earlier settlers of Webster Parish, they chose locations with safer water routes to reach their destination. Similar to early European settlers, they utilized the long lot system to organize their land parcels. The river geography offered rich alluvial soil perfect for farming, while narrow land strips granted essential river access.

You’ll find that the community’s anchor point became the Nazarene Baptist Church, established by Reverend Robert Morrison in 1889, about 1.5 miles north of where the marker stands today.

The original settlement pattern followed traditional Spanish land grant divisions, supporting both agriculture and community development along the riverfront.

River Access Benefits

Through its strategic positioning along the Mississippi River, Morrisonville’s river access points from Australia Point to Graceville provided essential economic and social benefits to its residents.

You’d find bustling boat launches supporting both commercial fishing operations and recreational activities, driving significant economic growth in the region. Local anglers regularly caught diverse fish species, including catfish, bass, and crappie, making it a prime destination for fishing enthusiasts. These access points served as gateways for tourism development, creating opportunities for local businesses ranging from fishing supply stores to hospitality services. The area’s proximity to the Bonnet Carre Anchorage made it a significant maritime transportation hub.

The river access also enhanced community life through outdoor activities and social gatherings. You could participate in fishing tournaments, regattas, and environmental education programs along these waterfront areas.

Well-maintained infrastructure, including safety measures and essential amenities, guaranteed that both visitors and residents could safely enjoy the river’s recreational and commercial opportunities while supporting local conservation efforts.

The Role of Nazarene Baptist Church

You’ll find the Nazarene Baptist Church stood as Morrisonville’s spiritual cornerstone since its founding by Rev. Robert Morrison in 1889, serving as both a religious sanctuary and community gathering space.

When environmental concerns from Dow Chemical forced the town’s relocation in 1990, the church’s leadership helped guide residents through their displacement to new communities called Morrisonville Estates and Morrisonville Acres.

Today, while the town itself has vanished, the church’s cemetery remains as hallowed ground, preserving the memories of generations who once called Morrisonville home.

Community’s Spiritual Anchor

The Nazarene Baptist Church, founded in 1889 by Reverend Robert Morrison, stood as the spiritual bedrock of Morrisonville’s African American community for nearly a century.

As a reflection of spiritual resilience, the church provided essential religious services while functioning as a crucial community center during the challenging era of segregation.

You’ll find that beyond regular worship services, the church fostered community healing through social gatherings, education initiatives, and mutual support systems.

In the face of environmental pressures from Dow Chemical’s vinyl chloride factory, the congregation maintained its role as a stabilizing force, offering solace and guidance to its members.

The church’s dedication to preserving African American spiritual traditions through music, preaching, and communal worship helped sustain cultural identity amid mounting pressures that would eventually lead to the community’s displacement.

Leadership Through Displacement

While enduring multiple forced relocations throughout the 20th century, Nazarene Baptist Church emerged as more than just a spiritual center – it became the driving force behind Morrisonville’s community resilience and collective decision-making.

During three major displacement events in 1921, 1931, and 1990, the church’s leadership provided essential historical advocacy, serving as an informal liaison between residents and external entities.

You’ll find that when environmental challenges arose, particularly from vinyl chloride contamination, the church stepped forward to coordinate responses and unite the community.

Founded by Rev. Robert Morrison in 1889, the church’s influence extended beyond religious matters, helping preserve African American heritage through each change.

Even after Morrisonville’s physical dismantlement, the church continued fostering social cohesion and guiding collective responses to industrial and environmental pressures.

Sacred Ground Remains Today

Standing as one of Morrisonville’s last physical remnants, Nazarene Baptist Church‘s sacred grounds continue to preserve the community’s legacy through its historic cemetery. Since its founding in 1889, the church has anchored the African American community‘s sacred history, serving as both a spiritual sanctuary and cultural cornerstone.

Today, while the town itself has vanished, you’ll find the churchyard maintained as hallowed ground, marking the final resting place of former residents. Local historical associations and descendants work tirelessly to protect this essential piece of cultural preservation.

The cemetery stands as a geographic monument to Morrisonville’s displaced community, featured in museum collections, oral histories, and documentary projects. You can still witness this enduring symbol of resilience through historical markers and exhibitions at the West Baton Rouge Museum.

Chemical Valley’s Dark Shadow

Situated along Louisiana’s industrial corridor, Morrisonville’s transformation from a peaceful farming community into a contaminated sacrifice zone began in 1958 when Dow Chemical constructed its massive vinyl chloride plant.

This industrial legacy brought devastating chemical exposure to residents, forever altering their way of life.

- Plant announcements blared directly into people’s homes, shattering the peaceful rural atmosphere.

- Toxic emissions invaded the community after Dow eliminated the green buffer zone.

- Your ancestors’ agricultural heritage gave way to the stark reality of petrochemical production.

- You’d find yourself in the heart of “Cancer Alley,” joining countless other Black communities impacted by industrial contamination.

- The vinyl chloride plant’s expansion to 1,400 acres physically consumed the land where generations had farmed.

The Dow Chemical Buyout

In 1989, you’ll find that Dow Chemical Company orchestrated a $7 million buyout of Morrisonville, marking a pivotal moment in the community’s history.

You’d learn that families who once called this historically Black community home received financial compensation packages, though the true cost of uprooting generations of history proved immeasurable.

Your understanding of the buyout’s aftermath would reveal that while Dow provided relocation assistance, many residents scattered to nearby towns, fundamentally altering the social fabric that had defined Morrisonville for generations.

Corporate Acquisition Process

After decades of industrial expansion in Louisiana’s chemical corridor, Dow Chemical initiated a thorough buyout of Morrisonville in 1989, marking the final chapter in the community’s century-long struggle with displacement.

Despite the appearance of corporate ethics, you’ll find that residents faced a stark choice that challenged their community resilience.

- Dow announced complete property purchases following the discovery of harmful chemicals in local water wells.

- Residents received ultimatums that their properties would become worthless if they refused to sell.

- Twenty families initially resisted but ultimately surrendered by 1993.

- The company relocated residents to Morrisonville Estates and Morrisonville Acres.

- Only cemeteries and a prayer site remained, requiring security clearance for family visits.

The systematic dismantling of this historic African American community reflected a pattern of corporate-driven displacement throughout Louisiana’s industrial corridor.

Financial Impact on Families

While Dow Chemical’s $7 million buyout package in 1989 appeared substantial on paper, the financial impact on Morrisonville’s families proved far more complex than mere monetary compensation.

You’ll find that displaced residents faced immediate challenges beyond property values, including the need to secure new housing, employment, and establish economic resilience in unfamiliar communities. The disruption affected their social networks and communal assets, which had historically provided essential financial safety nets.

Many families required additional financial assistance to navigate their relocation, with some struggling to find comparable housing or employment opportunities.

The true cost extended beyond immediate expenses, as residents dealt with potential health-related costs from prior pollution exposure and the long-term implications of leaving their established economic foundations behind.

Relocation Sites and Assistance

Through Dow Chemical’s coordinated relocation program in 1989, Morrisonville residents were dispersed primarily between two new communities: Morrisonville Estates in Iberville Parish and Morrisonville Acres in West Baton Rouge Parish.

While you’ll find the relocation challenges were significant, Dow provided financial compensation and support to help preserve the community’s identity during this shift.

- A wooden prayer site was established so you could still visit family graves

- You’d find remnants of the original town preserved, including the historic cemetery

- Community support networks helped families adapt to their new surroundings

- Many residents maintained connections despite geographical separation

- The move preserved some aspects of community identity through shared relocation sites

The complete relocation by 1993 marked the end of the original Morrisonville, though its legacy lives on through the relocated communities.

A Community’s Forced Exodus

The final exodus came in 1989 when Dow Chemical Company’s expansion forced residents to abandon their homes.

While they received compensation, you can’t put a price on historical memory and generational ties.

The displacement scattered families between Morrisonville Estates and Morrisonville Acres, leaving only cemeteries as evidence of the original community’s existence.

What Remains: Sacred Grounds

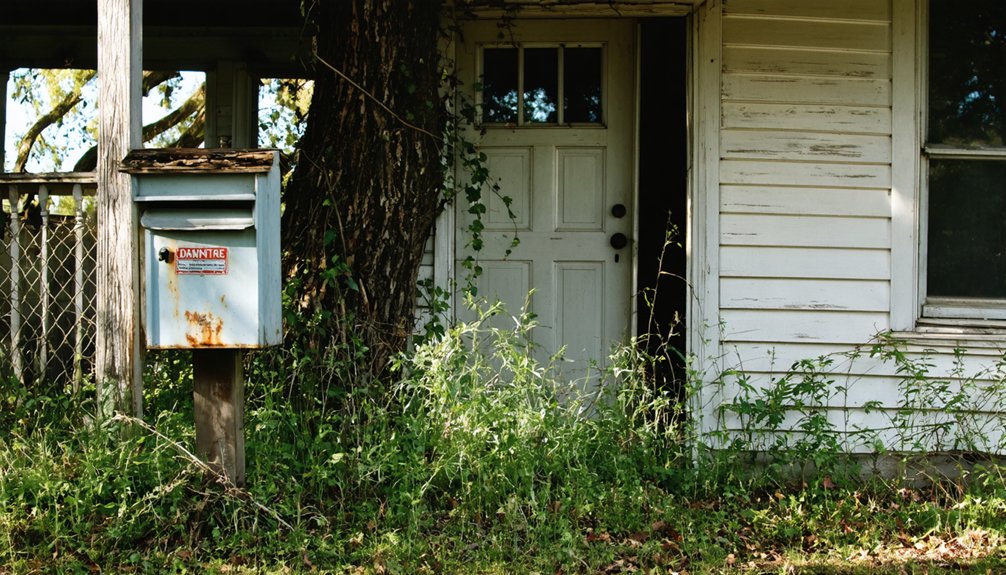

Standing as silent witnesses to Morrisonville’s vibrant past, sacred grounds now mark where a once-thriving African-American community flourished.

Today, you’ll find powerful symbols of community resilience in what remains:

- The historic Nazarene Baptist Church cemetery, dating to the late 1800s

- A wooden prayer site provided by Dow Chemical for visiting descendants

- A state historic marker revealed in 2004, telling the community’s story

- Graves of generations who built lives here after emancipation

- The original sacred ground of Rev. Robert Morrison’s 1889 church

These sacred preservation sites are all that’s left of Morrisonville’s physical presence.

Sacred ground remains the final testament to Morrisonville, preserving memories where a community once stood strong.

While industrial expansion forced the town’s relocation three times, these grounds continue to draw descendants, including Rev. Morrison’s seventh-generation relatives, who maintain their connection to this meaningful place.

Legacy of Environmental Injustice

Despite its vibrant history as a free Black settlement, Morrisonville’s fate exemplifies a broader pattern of environmental injustice that plagued African American communities along Louisiana’s Cancer Alley.

You’ll find the community’s historical significance reflected in decades of struggle against industrial expansion and toxic exposure, with residents facing carcinogens, mutagens, and rare diseases from nearby petrochemical facilities.

Though they’ve shown remarkable community resilience through grassroots organizing and protests, systematic regulatory failures left them vulnerable.

Louisiana’s delayed environmental protections – with air pollution laws arriving only in 1972 and LDEQ’s establishment in 1984 – allowed industries to operate unchecked for generations.

While Dow Chemical’s 1990 buyout scattered residents to new developments, the environmental injustices that erased Morrisonville continue to shape Cancer Alley today.

Remembering Lost Neighborhoods

Once a thriving free Black settlement, Morrisonville now exists primarily in memories, photographs, and oral histories passed down through generations of displaced families.

Community resilience shines through as you learn about this lost neighborhood through historical preservation efforts.

- Former residents gather annually to share stories of the close-knit community that once thrived along the Mississippi River

- Local historians have collected family photographs, maps, and documents to preserve Morrisonville’s cultural heritage

- Oral history projects capture the voices of elders who remember life before industrial expansion

- Community groups maintain a small memorial garden where the settlement once stood

- Digital archives now house recordings, images, and artifacts that tell Morrisonville’s story for future generations

You’ll find that these preservation efforts serve as both a tribute to what was lost and a tool for environmental justice advocacy today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Average Property Value During the 1989 Dow Chemical Buyout?

You won’t find exact property market values from the 1989 buyout, though it is understood Dow’s $7 million total economic impact suggests significant property values for that time period’s local market.

How Many Students Attended Morrisonville’s Local Schools Before the Final Relocation?

Time tells all tales. You’ll find that student enrollment reached around 86 at Morrisonville High School by 2025-2026, with school history showing a 7% growth over the previous five years.

Which Crops Were Primarily Grown by Early Morrisonville Farmers?

You’ll find cotton and sugarcane were dominant crops, as farmers utilized crop rotation and traditional farming techniques influenced by African American agricultural practices in the swampy terrain they worked.

What Were the Most Common Occupations of Morrisonville Residents in the 1950S?

Like moths to a flame, you’d find most residents working at Dow Chemical’s plant, though some maintained farming practices or ran local businesses to support the growing industrial workforce.

How Many Original Morrisonville Families Still Live in Morrisonville Estates Today?

You can’t determine the exact number of original families living in Morrisonville Estates today, as there aren’t any publicly available statistics tracking current residents from the original community.

References

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Morrisonville

- https://talk1470.com/ixp/33/p/7-louisiana-ghost-towns/

- https://www.westbatonrougemuseum.com/282/Morrisonville

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfT01KggipA

- https://www.reimaginerpe.org/book/export/html/7623

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morrisonville

- https://high.org/collection/community-remains-former-morrisonville-settlement-dow-chemical-corporation-plaquemine-louisiana/

- https://www.magersandquinn.com/product/MORRISONVILLE-LOUISIANA/22361742

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Morrisonville_Louisiana.html?id=kRiNtgAACAAJ

- https://www.wbrcouncil.org/569/Mississippi-River