Mowry, Arizona was a silver mining boomtown founded by Lt. Sylvester Mowry in 1860. You’ll find it in southeastern Arizona, where it once produced $1.5 million in silver and employed 300 workers. Its decline began when Mowry was imprisoned at Fort Yuma on Confederate sympathizing charges during the Civil War. Today, only adobe ruins, stone foundations, and a historic cemetery remain as evidence of the territory’s volatile mining past.

Key Takeaways

- Mowry was a silver mining town established in 1860 by Lt. Sylvester Mowry that produced approximately $1.5 million in silver.

- The mine experienced disruption during the Civil War when Mowry was imprisoned on Confederate sympathizing charges.

- At its peak around 1907, Mowry employed over 200 workers and ranked second in Arizona for lead production.

- The ghost town operated until 1956 when ASARCO withdrew, leaving ruins including adobe walls and a historic cemetery.

- Today, visitors can explore low adobe foundations, a collapsed mine shaft, and the original smelter site.

Silver Dreams: The Birth of a Mining Outpost

The Spanish colonial period marked the earliest mining efforts in what would become Mowry, where laborers worked the Patagonia Mine in southeastern Arizona’s mountains.

This remote operation remained relatively obscure until 1857, when American prospectors rediscovered the site, launching a new era of mineral extraction.

In 1860, Lt. Sylvester Mowry purchased the claim for $25,000, giving the mine its enduring name.

Situated at 5,499 feet in what’s now Santa Cruz County, the operation targeted silver-lead deposits formed during the Paleocene epoch.

Under Mowry’s direction, mining techniques evolved rapidly with twelve blast furnaces reducing ore into 70-pound bars for shipment.

Despite labor challenges managing a workforce of nearly 300 Mexican miners, the operation reportedly produced $1.5 million in silver, establishing itself as one of the territory’s most productive ventures.

Like many mining operations in the region, Mowry’s enterprise faced significant disruptions due to Apache raids that threatened transportation routes and worker safety.

After his controversial imprisonment at Fort Yuma, California for allegedly aiding the Confederacy, Mowry sold the mine to San Francisco investors for $2.5 million.

The Rhode Islander Who Built an Arizona Empire

You’ll find the convergence of Eastern refinement and Western ambition in Edward Julius Berwind, who leveraged his Rhode Island education to recognize Arizona’s silver potential.

Berwind’s substantial financial resources enabled him to transform Mowry from a modest mining claim into a regional economic powerhouse during the 1880s.

His empire’s prosperity proved fleeting, however, as fluctuating silver prices and resource depletion eventually undermined his once-thriving frontier investments, while his business approach mirrored the exploitative practices of his Berwind-White Coal Company which prioritized profits over worker safety.

Unlike Arizona’s copper production which has maintained national leadership since 1910, Berwind’s silver operations couldn’t sustain long-term economic stability.

Education Meets Frontier Dreams

Born into New England privilege in 1833, Sylvester Mowry would transform his elite West Point education into an ambitious frontier enterprise that shaped Arizona’s territorial destiny.

Graduating high in his class in 1852, Mowry applied military strategy to civilian ambitions after commissioning as a lieutenant. His West Point training proved invaluable when he became a vocal champion for Arizona’s territorial separation from New Mexico in 1856.

You’ll find Mowry’s education reflected in his methodical territorial advocacy at the Tucson convention and his strategic approach to publicizing Arizona’s potential to eastern investors. Mowry recognized the tremendous mineral wealth that existed in the region, which motivated his investment in Arizona’s future.

This Rhode Islander’s background prepared him to establish defensive stockades protecting his silver empire from Apache raids after purchasing the Patagonia mine in 1860. His scientific knowledge allowed him to author “The Geography and Resources” of the region, enhancing his reputation as an authority on Arizona’s potential.

Even facing imprisonment during the Civil War, his educational foundation equipped him to navigate frontier politics.

Silver Wealth, Fleeting Fortune

After purchasing the Patagonia Mine in 1860 for approximately $25,000, Sylvester Mowry transformed this modest acquisition into a thriving silver empire that would ultimately yield an estimated $1.5 million in precious metal.

You can trace the rise and fall of one of Arizona’s greatest silver fortunes through these key developments:

- The mine employed up to 300 men, primarily Mexican laborers, during peak operations.

- Multiple blast furnaces produced 70-pound silver bars despite frequent Apache raids.

- Lead was transported 250 miles to Guaymas, Sonora for European shipment.

- Mowry’s 1862 arrest on charges of aiding Confederates severely disrupted operations.

- By the 1870s, mining legacies faded as efficiency declined after the Civil War.

The mine’s impressive elevation of 5,499 feet provided strategic advantages for spotting approaching threats while presenting logistical challenges for ore transportation.

Mowry’s dream collapsed with his death in London in 1871, leaving behind a mining legacy that would change hands repeatedly in unsuccessful revival attempts.

War, Imprisonment, and Allegations of Confederate Support

The Civil War brought disaster to Lt. Sylvester Mowry when the government arrested him in 1862 on charges of “aiding and abetting the enemy” through his mine’s lead production for alleged Confederate use.

You’ll find that his detention at Fort Yuma lasted several months before authorities dropped the charges, during which time the government seized his mining operation.

During his imprisonment, a government-appointed receiver ruined equipment and effectively destroyed the mine’s operational capability.

Mowry maintained he was merely a political prisoner, though the damage was done—his once-thriving silver enterprise would never recover under his ownership.

Controversial Lead Production

During the tumultuous years of the Civil War, Mowry Mine’s lead production became embroiled in political controversy that would ultimately lead to its owner’s imprisonment. The lead market’s wartime ethics came under scrutiny as Sylvester Mowry faced accusations of selling this strategic resource to Confederate forces.

Despite the mine’s profitability being marginal in peacetime, the conflict dramatically increased demand for bullet materials.

The controversy surrounding Mowry’s operation included:

- Charges of “aiding and abetting the enemy” filed in 1862

- Imprisonment at Fort Yuma based on these allegations

- Absence of definitive proof despite serious accusations

- Political division in Arizona Territory influencing the case

- Eventual dropping of charges after months of detention

This controversy greatly impacted the mine’s reputation, causing decreased output and investor wariness in subsequent years.

Fort Yuma Detainment

Located approximately 160 miles east of Tucson, Fort Yuma served as the infamous detention site where Sylvester Mowry endured months of imprisonment following his 1862 arrest.

Historical records about Fort Yuma’s detainment practices during this period remain limited in public archives. What we do know comes primarily from Mowry’s own accounts and scattered military correspondence.

The facility, originally established for military conflicts with indigenous populations, pivoted during the Civil War to housing suspected Confederate sympathizers.

Mowry’s experience represents a contentious chapter in Arizona territorial history—one where accusations of Confederate support could result in property seizure and indefinite confinement without trial. The site’s strategic position overlooking the Colorado River made it an ideal location for monitoring movement along this important waterway.

While the full extent of Fort Yuma’s wartime detention protocols remains unclear, Mowry’s case highlights how military authority expanded during this tumultuous period. Fort Yuma was part of a network that later included the Yuma Territorial Prison, which would open in 1876 and become an important detention facility in Arizona’s history.

Political Prisoner Claims

Despite his northern origins and previous Republican leanings, Sylvester Mowry found himself arrested on June 13, 1862, charged with treason against the Union. The political implications were significant, as Union authorities viewed him as a dangerous Confederate sympathizer in the disputed Arizona territory.

Mowry’s claims of political persecution included:

- Being targeted despite selling ammunition only for Apache defense

- Detention without formal trial for nearly five months

- Military seizure of his mine without official confiscation orders

- Charges based largely on correspondence with Confederate officials

- Treatment as an enemy combatant despite civilian status

The case exemplified controversial wartime justice practices, where military commissions replaced civilian courts in contested territories.

Though eventually released on November 8, 1862, when Confederate forces retreated from Arizona, Mowry’s mining operations lay in ruins, effectively destroying his Arizona enterprises.

Peak Operations: Life in a Bustling Mining Community

As Sylvester Mowry acquired the mine in 1860 with Rhode Island investment backing, the bustling community of Mowry quickly evolved into one of southern Arizona’s most significant mining operations. By 1907, it ranked second only to Tombstone in lead production, employing over 200 workers.

Life in Mowry centered around demanding labor conditions, with miners—predominantly Mexican laborers—extracting not only lead and silver but also copper, gold, and various minerals.

Community dynamics were shaped by the mine’s remote location at 5,499 feet elevation in the Patagonia Mountains, where Apache raids presented constant threats. Despite these challenges, the settlement maintained relative stability through security measures and steady employment.

The installation of blast furnaces, a concentrator, and eventually a 100-ton-per-day smelter modernized operations, transforming Mowry into a functioning mining camp known as Trench Camp.

The Swift Decline and Abandonment After the Civil War

The Civil War brought devastating consequences to Mowry’s once-thriving mining operations when Union forces arrested Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry on June 13, 1862, charging him with treason for allegedly supplying lead ammunition to Confederate forces.

During Mowry’s six-month imprisonment, his property experienced systematic destruction that would trigger years of economic turmoil.

The community’s exodus began as multiple crises converged:

- Government officials deliberately destroyed mine equipment while Mowry was incarcerated

- Apache attacks intensified after Union troops evacuated their protective forts

- Hundreds of miners lost their jobs as operations ceased

- Legal battles for restitution proved futile despite Mowry’s eventual exoneration

- Subsequent owners failed to restore profitability

Exploring the Ruins: What Remains Today

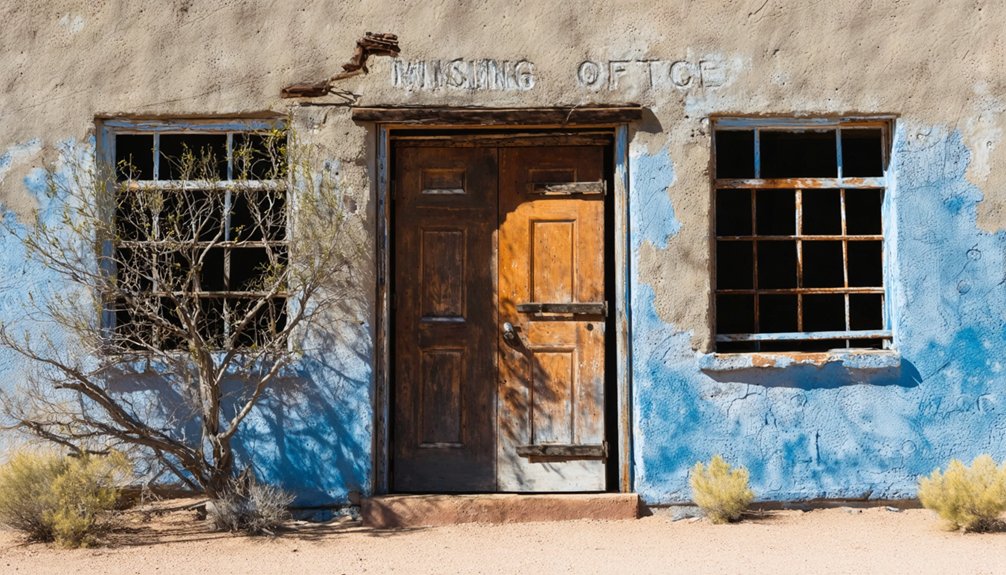

Visitors approaching the ruins of Mowry today will find a haunting collection of architectural remnants scattered across the Santa Cruz County landscape. The main townsite features low adobe and stone foundations, while areas north of FR 214 contain standing adobe walls and partially intact tin-roofed residences.

Time stands still at Mowry, where crumbling adobes and stone foundations whisper stories of Arizona’s mining past.

For ruins exploration, take the primary access road FR 214, with the main ruins accessible via a 0.2-mile eastern entrance. The historic cemetery remains preserved, offering glimpses into the lives of those who once called this mining community home.

Mining infrastructure persists throughout the property, including a collapsed mine shaft, stone powder house, and the original smelter site.

These elements, along with scattered equipment, represent vital aspects of historical preservation in this ghost town that operated until ASARCO’s withdrawal in 1956.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Role Did Apache Attacks Play in Mowry’s Decline?

Disrupted, destroyed, and decimated—Apache raids devastated Mowry’s operations. You’ll find they repeatedly ambushed miners, halted production, and ultimately demolished the town when the mines closed, creating an insurmountable mining impact.

Were Any Famous Individuals Connected to Mowry’s History?

You’ll discover several famous historical connections including founder Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry, his rival Edward Cross, mining pioneer David Harshaw, and early resident Orton Phelps, whose grave remains accessible near the ghost town.

Can Visitors Legally Collect Artifacts From the Ghost Town?

No, you can’t legally collect artifacts. Mowry’s ruins fall under federal legal regulations within Coronado National Forest, where artifact preservation laws protect historical remains from removal or disturbance.

What Supernatural Legends Are Associated With Mowry?

You’ll discover rich local folklore of Sylvester Mowry’s restless spirit, deceased miners’ ghosts, and unexplained phenomena. Ghost sightings, disembodied voices, and cemetery apparitions have been reported throughout the ruins.

How Did Mining Techniques at Mowry Differ From Other Sites?

Imagine standing 500 feet underground where few dared venture! Your freedom to explore Mowry’s historical techniques reveals deeper mining methods, industrial-scale processing, and integrated transportation infrastructure unmatched by contemporary Arizona operations.

References

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/classroom/mowry-az

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/mowry.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mowry_City

- https://www.apcrp.org/MOWRY012516/Mowry_Text_Master_012316_F.htm

- https://www.visittucson.org/listing/ghost-towns-of-harshaw-mowry-washington-camp-and-duquesne/6299/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i93wbwozujA

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_mining_in_Arizona

- https://south32hermosa.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Patagonia-Mining-History.pdf

- https://www.gvrhc.org/Library/MowryMine.pdf

- https://westernmininghistory.com/mine-detail/10109889/