You’ll find Mowry City’s ruins 25 miles north of present-day Deming, New Mexico, near the Mimbres River. Established in the late 1850s by Samuel J. Jones, Lewis S. Owings, and Robert P. Kelley, this mining settlement became an essential stagecoach hub along Cooke’s Wagon Road. Named after mining investor Sylvester Mowry, the town flourished briefly before declining during the Civil War. Today, adobe ruins and an abandoned open-pit mine tell a compelling frontier story.

Key Takeaways

- Founded in the 1850s near the Mimbres River, Mowry City was established as a mining town 25 miles north of modern Deming.

- The town served as a crucial stagecoach hub along Cooke’s Wagon Road, facilitating transportation and mail distribution in the region.

- Mowry City’s economy centered around silver mining, employing up to 300 workers and producing approximately $1.5 million during peak years.

- Apache attacks, Civil War disruptions, and the arrest of Sylvester Mowry in 1862 contributed to the town’s eventual decline.

- Today, Mowry City exists as a ghost town with visible adobe ruins, an open-pit mine, and a cemetery containing readable tombstones.

The Birth of a Speculative Settlement

As prospectors and settlers pushed westward across New Mexico Territory in the late 1850s, three ambitious speculators – Samuel J. Jones, Lewis S. Owings, and Robert P. Kelley – launched one of the era’s bold speculative ventures.

They set their sights on establishing a new town near the Mimbres River, about 25 miles north of present-day Deming.

To attract eastern investors to their economic dreams, they cleverly named the settlement after Sylvester Mowry, a well-known figure among financial circles back East. Like many mining towns of that era, they hoped to replicate the success of settlements like Lake Valley which would later yield 3.2 million ounces of silver.

Naming the settlement after the influential Sylvester Mowry was a calculated move to entice wealthy East Coast investors.

The location wasn’t random – they’d positioned their town at a strategic crossing on Cooke’s Wagon Road where the Butterfield Overland Mail route maintained a station.

They combined their land promotion scheme with the promise of nearby mining prospects, hoping to spark rapid growth through promotion rather than natural settlement patterns.

Key Players Behind the Town’s Development

Three ambitious partners – Samuel J. Jones, Lewis S. Owings, and Robert P. Kelley – leveraged their business and mining interests in Mesilla to establish Mowry City as a speculative venture.

You’ll find that while Sylvester Mowry lent his name to attract eastern investors, he wasn’t directly involved in the town’s development or operations.

The founders strategically positioned their settlement near key transportation routes, including the Rio Mimbres stage stop on the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line and the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach service.

The Ambitious Town Founders

Behind Mowry City’s ambitious development stood several key figures who orchestrated the town’s creation through calculated promotion and land schemes.

You’ll find Samuel J. Jones, a former Kansas sheriff, leading the charge alongside Lewis S. Owings and Robert P. Kelley – all three operating from their base in Mesilla near Las Cruces.

They crafted an elaborate plan to establish a new settlement, with Kelley’s connection to Sylvester Mowry proving particularly valuable.

By naming the town after the famous Mowry, they hoped to attract eastern investors to their venture.

The founders’ strategy centered on town promotion and leveraging Mowry’s reputation in the mining industry, especially given his recent $25,000 purchase of the Patagonia Mine in 1860.

Like many mining ventures in the region, they faced challenges from Apache attacks that hindered development and discouraged potential settlers.

Sylvester Mowry’s Investment Role

When Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry purchased the Patagonia Mine for $25,000 in 1860, he’d establish himself as a pivotal figure in the region’s mining development.

After renaming it the Mowry Mine, he immediately sought to expand operations by selling a one-fifth interest to eastern investors.

Mowry’s financing efforts proved challenging as he traveled between Arizona, San Francisco, and New York seeking capital for improvements.

His investment struggles intensified during the Civil War when he faced arrest on charges of aiding the Confederacy.

Though later cleared, the legal battles disrupted mine operations and wage payments.

Despite these setbacks, Mowry managed to develop substantial infrastructure, including 12 blast furnaces producing 70-pound silver bars.

He collaborated with his brother to construct a mill and smelter to process the extracted ore.

The mine would ultimately yield $1.5 million in silver during its peak years.

The area’s historical mining operations, particularly those run by Jesuit priests, had already proven the region’s rich mineral potential.

Stagecoach Station Management Leaders

As Mowry City evolved into an indispensable transportation hub in the 1860s, several key figures emerged to manage its important stagecoach operations.

Henry Lesinsky and Con Cosgrove led J.F. Bennett & Co.’s main mail line, while W.H. Wiley & Company handled the branch routes to Fort Bayard and Silver City.

The stagecoach management structure relied heavily on local business leaders.

Samuel J. Jones, Lewis S. Owings, and Robert P. Kelley promoted the town’s development as a significant stop.

R.V. Newsham and M. St. John supplied travelers through their merchant operations, while A. Voorhees and later “Old Man” Porter ran the town’s hotel.

Facing daily operational challenges, Dick Mawson and “Hairtrigger John” Gibson provided indispensable blacksmith services, keeping the coaches running through this crucial transportation corridor.

Life Along the Butterfield Stage Route

Through the rugged southwestern edge of New Mexico Territory, the Butterfield Stage Route carved a challenging path across desert and mountainous terrain, connecting St. Louis to San Francisco.

You’d have faced a grueling 25-day journey, paying about $200 (equivalent to $3,000 today) for the privilege of enduring extreme hardships.

At stage stops like Fort Fillmore and La Mesilla, you’d find brief respite from the harsh desert conditions. These essential hubs offered water, fresh horses, and shelter – though some were merely tents. A critical stretch between Dragoon Springs and Apache Pass had no water available except at the stations themselves. Along the way, passengers sometimes encountered the overland mail from San Francisco, which allowed for exchanging news updates.

You’d often walk alongside the coach through difficult passages, battling intense heat and thirst, especially during the dreaded 40-mile waterless stretch from Soldier’s Farewell.

The most dangerous segment lay between Cooke’s Spring Station and Fort Cummings, where numerous travelers met their end.

Mining Operations and Economic Impact

Once a thriving enterprise under Spanish colonists who employed native laborers, the Mowry Mine emerged as one of southern Arizona’s most significant silver operations after Mexican prospectors rediscovered it in 1857.

Under Lt. Sylvester Mowry’s ownership from 1860, the mine flourished with advanced mining techniques including multiple blast furnaces that produced 70-pound silver and lead bars. The operation included twelve blast furnaces working simultaneously to process the valuable ore. You’d have seen up to 300 workers, mostly Mexican laborers, operating under armed protection from Apache raids.

Armed guards protected hundreds of Mexican miners as they worked Mowry’s advanced silver operation against the threat of Apache attacks.

Despite generating an estimated $1.5 million in silver production, the mine faced serious economic challenges. The Civil War brought accusations of Confederate sympathies, leading to Mowry’s arrest and the mine’s temporary seizure.

Operations declined sharply after the war, though brief revivals occurred through the 1890s and during both World Wars, when manganese became an essential wartime resource.

Rise and Fall of a Transport Hub

You’ll find Mowry City’s early success centered on its strategic position along the Butterfield Overland Mail route, where it served as the essential Mimbres River Station connecting San Antonio to San Diego.

The town’s transport significance expanded when W.H. Wiley & Company established a branch line mail service in 1871, linking Fort Bayard, Silver City, and Pinos Altos to the main stagecoach routes. J.T. Chidester’s horseback mail service to Silver City helped maintain vital connections in the region.

While the mining boom brought increased passenger and freight traffic through Mowry City’s stagecoach networks, the arrival of the railroad in 1881 quickly rendered these traditional transport services obsolete.

Stagecoach Routes and Mail

During its heyday in the mid-19th century, Mowry City served as a crucial stagecoach hub on two major transport arteries: the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line and the Butterfield Overland Mail route.

You’d find stagecoach operations centered around the Rio Mimbres stop, where horses were exchanged and mail distribution occurred between destinations like Tucson, Mesilla, and El Paso.

The town’s position on Cooke’s Wagon Road made it significant for both passenger transport and mail delivery across the challenging Southwestern terrain.

Multiple companies competed for dominance in the 1870s, including Kerens and Mitchell Company and J.F. Bennett and Company, leading to reduced fares and faster routes.

However, when the railroad arrived in southern New Mexico in 1881, Mowry City’s importance as a stagecoach hub quickly faded.

Mining Boom Shapes Transport

The discovery of the Mowry Mine in 1860 transformed the region’s transportation landscape, establishing an essential hub for silver and lead production that would employ 300 workers and generate $1.5 million in silver yields.

You’d find wagon trains regularly traversing the 250-mile transport routes between the mine and Mexico’s Port of Guaymas, carrying precious metal bars and mining supplies.

The mine’s strategic placement of adobe reduction furnaces near the operation helped minimize transport costs, while the network of roads supported the flow of workers and equipment despite constant Apache raids.

Though the hub thrived initially, you’ll see how the Civil War marked its downturn.

After Union forces arrested owner Sylvester Mowry in 1862, the transport hub’s activity declined sharply, leading to its eventual abandonment by the 1870s.

Traces Left Behind: What Remains Today

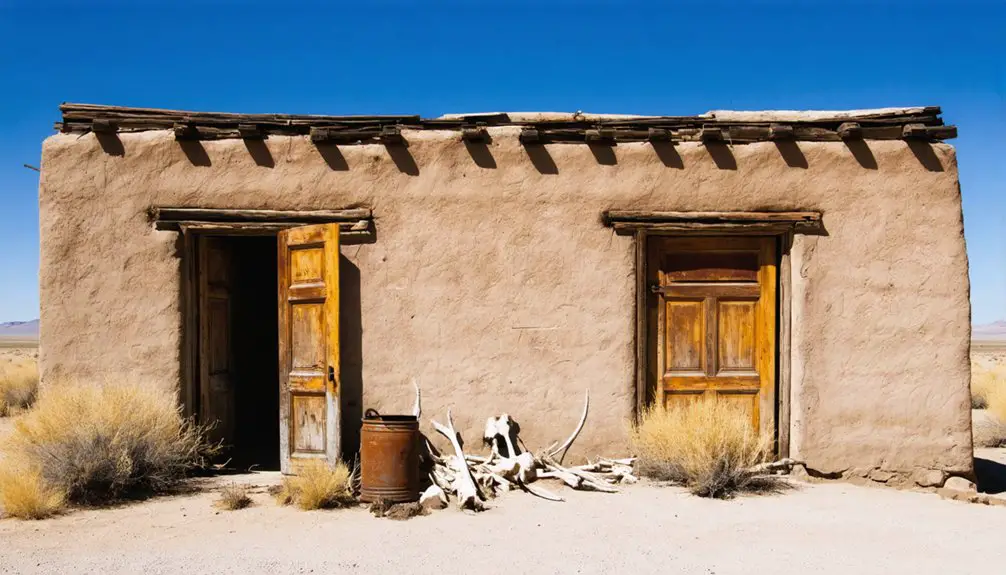

Modern visitors to Mowry City encounter a landscape dotted with adobe and stone ruins, where scattered remnants tell the story of this once-bustling settlement.

Similar to ghost towns in Arizona, the site provides a vital connection to the region’s past through its preserved structures and artifacts.

Archaeological discoveries reveal fragments of daily life, from glass shards and metal artifacts to mining equipment preserved beneath crumbling adobe walls.

Like many abandoned settlements, natural disasters contributed significantly to the town’s decline and eventual desertion.

You’ll find environmental decay has taken its toll, as desert winds and sandy soil gradually wear away at the remaining structures.

However, several key features remain:

- A maintained cemetery with readable tombstones, offering glimpses into the lives of early settlers

- The imposing semi-truck sized open-pit mine, a symbol of the area’s mining heritage

- Foundations of the Christian Endeavor building and scattered mercantile structures, still visible among the rugged terrain

The site’s position along Cooke’s Wagon Road and the Mimbres River continues to mark its historical significance.

Historical Lessons From a Lost Town

As Mowry City’s rise and fall illustrates critical patterns of frontier development, you’ll find its story packed with valuable lessons about economic vulnerability, military dynamics, and agricultural innovation in the American Southwest.

You can trace the town’s economic resilience through its adaptability – from stage stop economics to mining ventures and agricultural enterprises. Yet its dependence on single industries proved fatal when the railroad bypassed it.

The challenges of cultural interactions between settlers and Apache populations highlight the complex nature of frontier expansion, while John Brockman’s innovative farming methods demonstrate how settlers adapted to harsh environments.

Military presence through Camp Mimbres reveals the delicate balance between defense and settlement, showing how security concerns shaped development patterns in ways that still influence Southwest communities today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Mowry City Ever Involved in Any Significant Native American Conflicts?

You’ll find that Native American treaties failed to protect Mowry City settlers, who faced persistent Apache attacks in the 1860s, leading to the settlement’s early abandonment during widespread regional conflicts.

What Was the Maximum Population Recorded During Mowry City’s Peak Years?

Like finding a needle in a haystack, you’ll discover precise historical demographics are elusive. Population growth records suggest a maximum of several hundred residents during peak years, though exact numbers weren’t officially documented.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness Reported in Mowry City?

You won’t find evidence of major crime incidents in historical records, except for Sylvester Mowry’s 1862 arrest for selling lead to Confederates, which was more political than typical law enforcement action.

What Types of Businesses and Services Existed in the Town?

Living high on the hog, you’d find stagecoach stops, blacksmith shops, general stores, hotels, and mining operations. Local merchants served travelers, while grist mills and supply stores supported nearby settlers.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Visit or Stay in Mowry City?

You won’t find any famous visitors of historical significance here – records don’t show any notable figures staying in town, though California Volunteers garrisoned nearby Camp Mimbres in 1863-1864.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mowry_City

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O_1iT_a-Wzw

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/

- https://offroadpassport.com/forums/topic/3460-mowry-ghost-town-and-corral-canyon/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_New_Mexico

- https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/64000518_text

- https://www.mininghistoryassociation.org/Journal/MHJ-v6-1999-Spude.pdf

- https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1944&context=nmhr

- https://archive.org/download/historyofnewmexi02paci/historyofnewmexi02paci.pdf

- https://www.apcrp.org/MOWRY012516/Mowry_Text_Master_012316_F.htm