North Bloomfield, originally called “Humbug City,” transformed into a bustling hydraulic mining center with 2,000 residents during California’s Gold Rush. You’ll discover preserved mid-19th century buildings like the Hotel de France, general store, and church amid a landscape forever altered by massive water cannons that blasted hillsides. Judge Sawyer’s landmark 1884 environmental ruling ended the destructive mining practices, effectively creating America’s first environmental protection precedent. The scarred terrain tells a compelling story of boom, bust, and reckoning.

Key Takeaways

- North Bloomfield transformed from a booming hydraulic mining center with 2,000 residents to a preserved ghost town after environmental regulations.

- Originally named “Humbug City,” the settlement evolved through several name changes before becoming North Bloomfield in 1857.

- The 1884 Sawyer Decision, America’s first major environmental protection ruling, ended hydraulic mining operations that devastated local ecosystems.

- Visitors can explore preserved Gold Rush-era buildings including the Hotel de France, saloon, church, and general store.

- Located within Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park, the ghost town features over 20 miles of hiking trails through dramatic mining landscapes.

From “Humbug” to North Bloomfield: The Naming Journey

When prospectors first settled along the creek that would become the heart of a bustling mining community, they bestowed upon it the unflattering name “Humbug City.” This designation stemmed directly from the frustration of miners who, in the early 1850s, followed the boastful claims of a fellow prospector only to discover minimal gold deposits.

As you explore the Humbug history, you’ll find that by 1857, residents craved respectability. They held a mass meeting to rename their settlement “Bloomfield,” inspired by wildflowers blooming along the creek.

However, postal confusion with another Bloomfield in Sonoma County forced yet another change. The Bloomfield significance grew when residents added “North” to distinguish their town, coinciding with its growth into a hydraulic mining center with over 2,000 residents at its peak. The area later became one of California’s most productive mining operations, with the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company consolidating individual claims by 1860. The establishment of a post office in 1857 marked an important milestone in the town’s development and official recognition.

Gold Rush Origins and Early Settlement

The story of North Bloomfield began long before its name change from “Humbug City,” tracing back to a fateful discovery in the spring of 1851.

Three prospectors—Roger and Owen McCullough with Owen Marlow—unearthed rich placer deposits near Humbug Creek, inadvertently launching the settlement’s colorful history.

When one of their group broke secrecy after drinking in Nevada City, nearly 100 disappointed prospectors followed him back, dubbing the area “Humbug.”

A resilient few stayed behind, establishing a mining camp that grew steadily through 1853 as gold discovery techniques evolved.

Early miners relied on simple panning methods, but the adoption of hydraulic mining techniques revolutionized extraction possibilities.

The area would later become home to the Malakoff Mine, established in 1866 as the largest hydraulic gold-mining operation of its time.

In 1857, the growing settlement officially changed its name to North Bloomfield, shedding its unflattering “Humbug” nickname for good.

Despite facing boom-and-bust cycles and near abandonment during the 1860s drought, North Bloomfield’s rich deposits would soon attract substantial investment from San Francisco financiers.

The Rise of Hydraulic Mining Technology

When you walk the streets of North Bloomfield today, you’re treading the grounds where miners once wielded powerful monitors—iron water cannons developed by Anthony Chabot in 1855—that could blast entire hillsides apart in search of gold.

Your path through town follows the same routes where millions of tons of debris once flowed downstream, choking rivers, flooding farmlands, and ultimately triggering one of America’s first major environmental legal battles.

Judge Lorenzo Sawyer’s landmark 1884 decision effectively ended North Bloomfield’s mining heyday, establishing the precedent that industrial progress couldn’t come at the expense of the larger community’s welfare. This ruling came after the destructive practices had yielded approximately 11 million ounces of gold throughout California by the mid-1880s.

The mining operations in North Bloomfield were part of a larger economic boom that created hundreds of jobs in the region while simultaneously causing devastating environmental damage.

Powerful Water Cannons

Revolutionary in both concept and execution, hydraulic mining transformed the California gold mining landscape when it emerged near North Bloomfield in 1853.

Massive water cannons, known as “monitors,” became the heart of this mining innovation, blasting hillsides with focused jets that efficiently dislodged gold-bearing gravel unreachable by traditional methods.

You’ll find these engineering marvels operated continuously in two 12-hour shifts, processing an astonishing 100,000 tons of material daily at peak production.

The North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company deployed seven powerful monitors, creating unprecedented water erosion that quickly freed precious metals from mountainsides.

Their operation required extensive infrastructure—100+ miles of canals and flumes feeding water from mountain reservoirs through a sophisticated delivery system. The company utilized approximately 25 million gallons of water each day to maintain their intensive mining operations.

Electric lighting, powered by hydraulic generators, enabled round-the-clock mining and maximized the cannons’ productivity.

This innovative mining approach eventually faced legal challenges that culminated in the landmark Sawyer decision of 1884, which effectively ended large-scale hydraulic mining operations in California due to environmental concerns.

Environmental Devastation Unleashed

As hydraulic mining operations expanded throughout Nevada County in the mid-1850s, their devastating environmental impact quickly became evident across California’s waterways.

The massive Malakoff Diggins operation alone washed up to 100,000 tons of gravel daily into Humbug Creek and the Yuba River, transforming crystal-clear streams into muddy, polluted waterways.

You’d have witnessed entire hillsides disappearing as monitors blasted away the landscape. Mercury-laden sediments poisoned agricultural fields downstream, while debris rendered the Sacramento and Yuba rivers unnavigable.

Farmers watched helplessly as their lands were buried under mining waste.

This destruction ultimately sparked California’s first environmental battle, leading to pioneering mining regulations through the Sawyer Decision of 1884.

Today, ecological restoration efforts continue at sites like Malakoff Diggins, addressing the environmental wounds inflicted during this era.

Sawyer’s Decision Impact

The rise of hydraulic mining technology permanently altered California’s gold country landscape long before Judge Sawyer’s landmark 1884 decision curbed its devastation.

You can trace the judge’s 225-page ruling as America’s first environmental law, establishing protections against industrial pollution that reshaped mining practices nationwide.

Sawyer’s legacy extended beyond merely prohibiting debris dumping into waterways. His decision forced North Bloomfield Mining Company to dramatically restructure operations, slashing profit margins and triggering widespread industry change.

The powerful water cannons used in hydraulic mining had devastated entire hillsides and ecosystems before being regulated.

By 1886, the company faced substantial fines for violating the new regulations.

The 1893 Caminetti Law strengthened environmental regulations further, requiring licensing permits for all hydraulic mining.

North Bloomfield’s refusal to comply brought additional penalties, ultimately contributing to Malakoff Diggins’ closure in 1910—the end of an environmentally destructive era.

Environmental Devastation and the Sawyer Decision

When you visit Malakoff Diggins today, you’ll witness the stark remnants of hydraulic mining‘s devastating power, where entire mountainsides were literally blasted away, leaving behind the surreal, eroded landscape visible in the park.

The environmental impact extended far beyond the immediate mining area, as millions of tons of debris and silt washed downstream, clogging rivers, triggering catastrophic flooding in farming communities like Marysville, and altering waterways all the way to San Francisco Bay. The town experienced a rapid boom period ending in the early 1880s as environmental concerns mounted.

This widespread destruction ultimately prompted Judge Lorenzo Sawyer’s landmark 1884 ruling that effectively halted hydraulic mining operations, establishing one of America’s first environmental protection legal precedents.

Mountains Literally Washed Away

Towering mountains that once dominated the landscape of Nevada County literally disappeared beneath the relentless assault of hydraulic mining operations at North Bloomfield during the late 19th century.

The devastating mountain erosion occurred as miners blasted away hillsides with 25 million gallons of water daily, leaving ecological scars visible more than 130 years later.

- Entire mountainsides vanished as powerful water cannons pulverized ancient rock formations

- Hundreds of cubic tons of earth were washed away daily, forever altering the natural landscape

- Malakoff Diggins’ massive scars remain as evidence of man’s capability to reshape nature

- Stripped vegetation and topsoil created barren wastelands resistant to natural recovery

- Mercury contamination compounded the environmental catastrophe, poisoning waterways downstream

These environmental wounds eventually led to the landmark Sawyer Decision of 1884, America’s first major environmental ruling.

Rivers Clogged Downstream

As mountains crumbled beneath hydraulic cannons at North Bloomfield, devastating consequences flowed downstream where rivers choked on millions of tons of mining debris.

The Yuba and Feather rivers carried sediment that buried farmlands under sterile slickens, destroyed crops, and ruined once-fertile soil.

These mining impacts devastated local communities as clogged waterways triggered catastrophic floods around Marysville and Sacramento.

River health plummeted—salmon populations crashed as mercury contamination poisoned aquatic ecosystems.

The farmers fought back. In 1884, the landmark Woodruff v. North Bloomfield case resulted in Judge Sawyer’s decisive ruling: “All tailings must stop.”

This first major California environmental law protected agricultural interests over mining profits, though enforcement proved challenging.

Despite companies’ attempts at mitigation through dams and holding ponds, the environmental damage had already forever altered the landscape.

Daily Life in a Booming Mining Community

The bustling streets of North Bloomfield hummed with activity during the town’s golden era of the 1860s and 1870s, transforming what was once a modest placer mining camp called “Humbug City” into a thriving community of 1,200 residents.

Mining camaraderie developed in this frontier town where operations ran continuously, with men working shifts around the clock at the massive Malakoff Mine.

- You’d find up to eight saloons serving as social hubs for weary miners.

- After long shifts, you could choose between several hotels for lodging.

- Your daily needs were met by local dry goods stores and breweries.

- You’d witness the stark contrast between solo prospectors and corporate mining operations.

- Your livelihood would rise and fall with the town’s mining fortunes, facing frontier challenges together.

Architectural Heritage and Preserved Structures

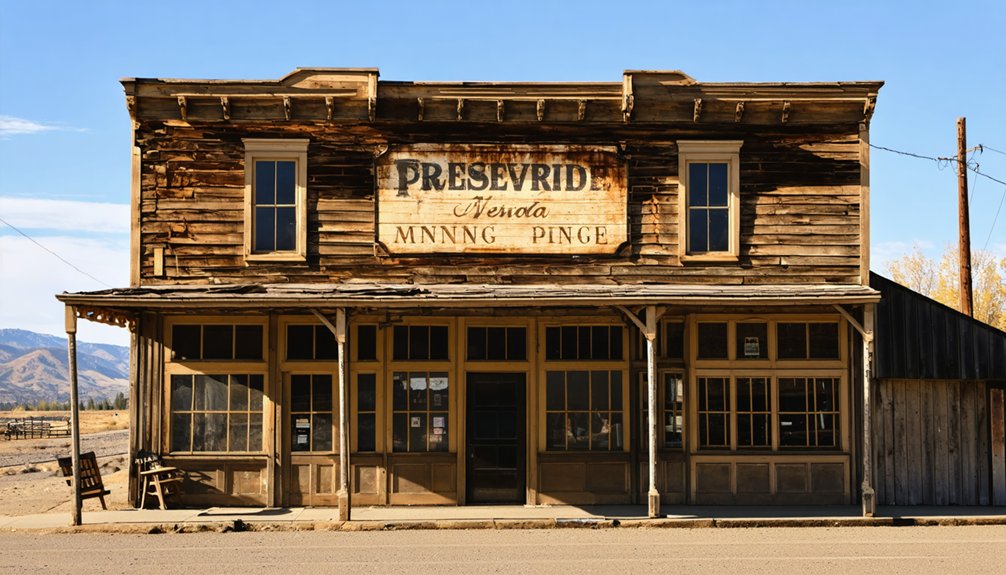

When you stroll along North Bloomfield’s main street today, you’re witnessing a remarkable collection of mid-19th century Gold Rush architecture, characterized by simple wooden structures with board and batten or clapboard siding topped by shingled or sheet iron roofs.

The most striking example of adaptive reuse stands in the former Civil War guard hall, which miners relocated from Bridgeport and later converted into a church during the 1860s.

White picket fences frame several preserved buildings maintained in “arrested decay”—deliberately conserved rather than fully restored—offering an authentic glimpse into the functional yet charming aesthetic that defined California’s mining boomtowns.

Gold Rush Building Styles

North Bloomfield’s architectural heritage reveals itself through the distinctive Gold Rush building styles that have survived since the town’s 19th-century heyday. As you wander these historic streets, you’ll witness the pragmatic design philosophy that defined mining town architecture—simple rectangular forms built primarily with local timber in board and batten, clapboard, or channel rustic styles.

- Wood-frame construction dominates the landscape, reflecting the abundant forest resources available to early settlers.

- High-pitched, originally shingled roofs (many later replaced with sheet iron) showcase practical adaptations to the Sierra Nevada climate.

- Canopied porches extend living and working spaces, merging indoor comfort with outdoor functionality.

- Commercial buildings like the McKillian & Mobley General Store stand alongside service structures and residences.

- Innovative mining infrastructure, including the remarkable 7,800-foot drainage tunnel, demonstrates gold rush engineering ingenuity.

White Picket Preservation

Surrounded by the rugged Sierra Nevada wilderness, North Bloomfield’s white picket fences stand as charming sentinels of preservation, defining property lines just as they did during the town’s 1850s heyday.

You’ll find these carefully maintained fences framing the McKillian & Mobley General Store, Smith & Knotwell Drugstore, and King’s Saloon—each restoration adhering to strict historical authenticity.

Park staff and volunteers battle constant weather exposure, replacing deteriorated boards with period-appropriate materials.

The simple rectangular forms with minimal decoration reflect mid-19th century California aesthetics, painted white as was standard practice.

Walking between these structures, you’ll appreciate how fence maintenance creates visual continuity while interpretive signs explain their significance.

Despite challenges of sourcing original materials and securing funding, these preserved architectural boundaries transport you directly into Gold Rush daily life.

Civil War Guard Hall

Beyond the white picket fences lies one of North Bloomfield’s most historically significant structures—the Civil War Guard Hall.

Originally built around 1859-1860 in Bridgeport as a Union armory, this two-story frame building was commanded by Captain Frank Coffey for Military Training of Civil War recruits.

When Bridgeport declined, the structure was relocated to Birchville and repurposed as St. Columncille’s Catholic Church.

- Constructed specifically for training soldiers destined for Civil War deployment

- Relocated twice, finally finding permanent home at Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park

- Completely renovated through public subscription funding

- Now serves all denominations while maintaining its Catholic furnishings

- Represents authentic gold rush architectural heritage through its non-masonry construction

You’ll find this historical gem open weekends from spring through September, offering a tangible connection to California’s Civil War contributions.

The Decline: When Gold Dreams Faded

Although North Bloomfield once bustled with the fevered activity of fortune-seekers, its decline began in the early 1860s when surface gold deposits became increasingly scarce. Miners departed en masse for new opportunities in Canada and Nevada, leaving the town’s population dwindling rapidly.

The shift to hydraulic mining techniques initially offered hope, with massive operations processing 50,000 tons of gravel daily. However, this revival proved temporary.

Judge Lorenzo Sawyer’s landmark 1884 decision in *Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company* effectively ended unrestricted hydraulic mining, citing environmental destruction to waterways and farmlands.

Despite community resilience through bootleg operations, the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company accumulated unsustainable fines, closing in the late 1890s and officially dissolving by 1910.

The town’s population continued its inexorable decline into ghost town status.

Cultural Diversity in the Sierra Foothills

While most people associate the California Gold Rush with fortune-seeking miners, the Sierra Foothills region where North Bloomfield emerged had already been home to a rich tapestry of Indigenous cultures for millennia.

The Miwok, Nisenan, and Yokuts tribes demonstrated remarkable Indigenous resilience despite the upheaval brought by Spanish colonization and later, the Gold Rush’s devastating impacts.

- The Nisenan tribe, displaced to Nevada City Rancheria, maintained their identity despite encroachment.

- Cultural adaptation occurred as tribes preserved ceremonies while incorporating new elements.

- Traditional structures like sweat lodges continued to serve essential community functions.

- Multilingualism became a survival strategy as different cultures collided in the foothills.

- Despite forced relocations, Native communities preserved distinct languages and cultural practices.

These Indigenous communities persisted through centuries of challenges, their cultural legacies interwoven with the region’s mining history.

Visiting North Bloomfield Today

Every modern-day visitor to North Bloomfield steps back in time to experience one of California’s most authentic ghost towns, nestled within the scenic expanse of Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park.

You’ll find the park 16 miles northeast of Nevada City, accessible via 8 miles of unpaved road (high-profile vehicles recommended).

Once there, explore over 20 miles of hiking trails through dramatic mining landscapes and restored canyon walls.

The ghost town’s preserved Gold Rush-era buildings—including the Hotel de France, saloon, church, and general store—open weekends from 10am-5pm during spring and summer.

Join ranger-led Saturday tours year-round for deeper historical insights.

Even when buildings are closed, you’re free to wander the grounds, peek through windows, and absorb the historical atmosphere unencumbered by modern distractions.

Legacy of North Bloomfield in California’s History

When gold was discovered near Nevada City in 1851, few could have predicted that the humble settlement initially named “Humbug” would become one of California’s most significant tributes to the environmental consequences of Gold Rush mining.

North Bloomfield’s evolution from boom town to ghost town encapsulates California’s complex mining legacy—one of prosperity, destruction, and eventual reckoning.

- The 1884 Sawyer Decision halting hydraulic mining established America’s first major environmental protection ruling

- The scarred landscape of Malakoff Diggins serves as a permanent reminder of unchecked resource extraction

- North Bloomfield’s preserved buildings tell the story of diverse communities that shaped California

- The town’s decline mirrors hundreds of similar ghost towns across the West

- Today’s preservation efforts guarantee future generations can witness this pivotal chapter in Western expansion

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal Activities or Ghost Stories From North Bloomfield?

Unlike many ghost towns, you’ll find North Bloomfield has surprisingly few documented ghost sightings or haunted locations, as its decline stemmed from environmental restrictions rather than tragic events typically spawning paranormal lore.

What Happened to the Chinese Cemetery That Once Existed There?

Thousands of forgotten souls vanished from North Bloomfield’s Chinese cemetery when remains were disinterred in the 1940s-50s. You’ll find Chinese influence erased as countrymen followed traditional customs, returning ancestors’ bones to their homeland.

Can Visitors Pan for Gold at Malakoff Diggins Today?

Yes, you’ll enjoy gold panning at Malakoff Diggins every Saturday at 3pm near the Visitor Center. You’re free to pan in Humbug Creek, but visitor regulations permit only pans and hands—no other equipment.

How Did Residents Access Healthcare During the Mining Boom?

Like wounded canaries, you’d seek mining medicine through local drugstores, visiting practitioners, and traditional remedies. For serious ailments, you’d endure difficult journeys to Nevada City for proper healthcare access.

What Native Tribes Originally Inhabited the North Bloomfield Area?

The Nisenan people, part of the Maidu language group, originally inhabited your region. Their tribal history spans thousands of years, with cultural significance deeply rooted in Sierra Nevada’s foothills landscape.

References

- https://www.thosesomedaygoals.com/2014/12/01/ghost-towns-north-bloomfield-california-aka-humbug/

- https://www.sierrafoothillsliving.tv/experience-the-mystique-of-north-bloomfield-a-preserved-california-ghost-town/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1hAcyH1XndA

- https://outerrealmz.com/north-bloomfield/

- http://malakoff.com/goldcountry/northblo.htm

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/north-bloomfield-malakoff-diggins/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/california/north-bloomfield/

- https://www.sierragoldparksfoundation.org/page/malakoff-diggins-state-historic-park/

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-209973.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malakoff_Diggins_State_Historic_Park