You won’t find Notomidula on standard ghost town tours or maps. This obscure Gold Rush settlement in Mariposa County‘s Sierra Nevada mountains flourished briefly after 1848 before declining in the late 1860s as gold yields diminished. Unlike better-documented abandoned towns, Notomidula’s history remains largely mysterious, with minimal physical remnants where miners once gathered at saloons and worked creek confluences. The wilderness has reclaimed nearly all traces of this enigmatic chapter in California’s frontier past.

Key Takeaways

- Notomidula was a small, obscure mining settlement in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains during the Gold Rush era.

- Located in Mariposa County near creek confluences, Notomidula operated as a placer mining outpost with minimal historical documentation.

- The settlement declined in the late 1860s due to depleted gold yields, with population dropping to fewer than fifty by 1875.

- Today, Notomidula has been reclaimed by wilderness with virtually no remaining structures or signage for visitors.

- Accessing this historical site requires moderate to advanced hiking skills and self-sufficiency as it’s one of Yosemite Valley’s most obscure locations.

The Forgotten Mining Outpost of Mariposa County

Nestled within the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains of California, Notomidula stands as one of Mariposa County‘s least documented mining settlements from the Gold Rush era.

You’ll find it situated near creek confluences, similar to neighboring Dog Town, where miners once employed rudimentary placer mining techniques to extract gold from stream beds.

Unlike larger boomtowns that have extensive historical records, Notomidula operated as a small but essential outpost for prospectors working the surrounding hills.

The settlement’s brief existence left few historical artifacts beyond scattered foundations and occasional mining implements.

What remains tells the story of transient populations who came seeking fortune but abandoned the site when gold yields diminished.

Its geographic isolation ultimately sealed its fate, transforming it into another silent memorial to California’s boom-and-bust mining legacy. Like many smaller ghost towns, Notomidula embodies the transient nature of human settlements dependent on finite resources. The area typically requires 4-wheel drive vehicles to access, making exploration challenging for modern visitors interested in this forgotten piece of mining history.

Gold Rush Origins and Settlement Patterns

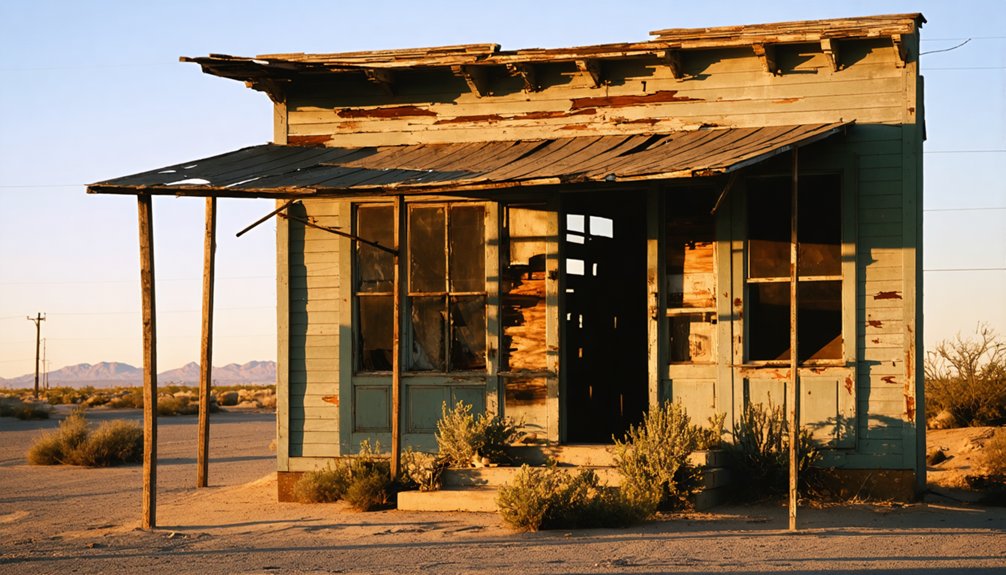

You’ll find Notomidula’s crude wooden structures reveal the hasty construction typical of Sierra Nevada boomtowns, where thousands of fortune-seekers erected temporary shelter with whatever materials lay at hand.

These makeshift settlements sprang up overnight following Marshall’s 1848 discovery at Sutter’s Mill, transforming California’s population from 14,000 to nearly 100,000 by the end of 1849.

Prospectors’ desperate hopes for instant wealth drove them to endure primitive conditions, crowding into canvas tents and rough-hewn cabins while dreaming of the gold that might await in nearby streambeds. The influx included diverse groups from around the world, with Chinese immigrants comprising a significant portion of the foreign miners who faced discrimination and targeted violence in the goldfields. Many travelers endured the treacherous 2,000-mile overland route with its numerous hazards including disease outbreaks and harsh terrain.

Hastily Built Settlements

Following the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill on January 24, 1848, the California landscape transformed almost overnight as hastily constructed settlements sprouted wherever precious metal was found.

You’d have witnessed tent cities rising within weeks, accommodating transient populations that swelled from mere hundreds to tens of thousands in months. The influx of forty thousand prospectors disembarking in San Francisco contributed to this dramatic population growth.

San Francisco itself experienced extraordinary expansion, growing from a population of 1,000 in 1848 to approximately 25,000 by 1849, becoming the central hub for mining-related commerce.

The hasty construction reflected miners’ urgent need to access gold deposits quickly.

With lumber scarce, prospectors repurposed materials from abandoned ships, converting vessels into makeshift buildings that served as hotels, saloons, and even jails.

These improvised structures characterized settlements like Notomidula, where expediency trumped permanence.

Prospectors’ Desperate Hopes

The desperate hopes of prospectors ignited when James W. Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill on January 24, 1848.

You’d have joined some 300,000 fortune seekers flooding California between 1848-1855, drawn by mining legends of river gravels yielding instant wealth.

The prospect of striking it rich seemed tantalizingly possible during the early rush. You might’ve employed “coyoteing,” digging shafts up to 43 feet deep or diverted entire rivers to expose gold-bearing deposits.

These prospecting challenges were formidable, yet fueled by dreams of social mobility.

Following President Polk’s official gold confirmation, California transformed overnight. By summer 1848, approximately 80,000 miners had arrived, dramatically changing California’s population from just 8,000 non-natives earlier that year.

Despite your hopes, wealth typically accrued to merchants rather than miners. Settlements near promising deposits grew chaotically, with those diversifying beyond mining surviving while others became ghost towns after deposits vanished.

Daily Life in Notomidula’s Heyday

You’d have found daily life in Notomidula characterized by the rustic simplicity of hastily constructed log cabins and wooden structures, where miners returned after exhausting days searching for gold.

Community gatherings at the settlement’s saloon offered rare respite from isolation, with music, storytelling, and shared meals strengthening bonds among the mainly male population. Similar to many California settlements, Notomidula experienced a rapid decline due to resource depletion as gold veins ran dry. The settlement maintained a state of arrested decay much like Bodie, with structures remaining as they were left after abandonment.

Your work would have consumed most waking hours, with recreation limited to simple card games, occasional hunting expeditions, and celebrations following successful gold strikes.

Rustic Mining Living

Life in Notomidula during its mining heyday embodied the quintessential hardships and modest pleasures of Sierra Nevada boomtowns.

You’d have called a simple wooden shack or canvas-roofed cabin home, warming yourself by a crackling wood stove during bitter winter nights. Daily sustenance came from communal kitchens serving hearty meals of beans, salted meat, and hardtack—fuel for dawn-to-dusk labor in the mines.

The mining techniques you’d master included backbreaking sluicing, panning, and later hydraulic operations that transformed the landscape. Like other mining camps in the Blue Lead section, Notomidula was easily accessible to visitors wanting to witness gold-digging operations.

Your social life revolved around the camp’s rudimentary establishments—the saloon, general store, and blacksmith. You’d barter goods using gold dust as currency, forming tight bonds with fellow miners.

Despite rampant illness from contaminated water and the constant threat of mining accidents, communal living fostered resilience in this harsh frontier existence.

Community Gatherings

Despite isolation from larger population centers, Notomidula fostered a vibrant social ecosystem centered on communal gatherings that punctuated the rhythm of mining life.

You’d find yourself drawn to the saloon or general store almost daily, where social bonds were strengthened through conversation and shared experiences. Community traditions emerged through regular dances, holiday celebrations, and impromptu musical events held in the town’s modest public buildings.

- Church socials and school functions served as anchors for families seeking structure amid frontier uncertainty.

- Traveling performers occasionally brought outside entertainment, creating town-wide events that residents discussed for months.

- Mutual aid gatherings formed the backbone of survival, where you’d join neighbors to rebuild after fires or accidents.

Work and Recreation

While miners toiled through grueling shifts in Notomidula’s network of ore-rich tunnels, their daily existence balanced backbreaking labor with necessary diversions that sustained both body and spirit.

Unfortunately, historical records about Notomidula’s specific work conditions and recreational activities remain elusive in available documentation. This gap in California’s mining heritage leaves us without concrete details about how residents spent their days extracting precious metals or their evenings unwinding from the physical demands of frontier life.

Unlike better-documented ghost town history in places like Bodie or Calico, Notomidula’s daily rhythms—from mining techniques to social gatherings—await further research through county archives or firsthand accounts.

The absence of these details reminds us how easily communities can fade from historical memory without deliberate preservation efforts.

Mining Operations and Economic Activity

Little is documented about Notomidula’s mining operations, which presents a historical enigma for researchers studying California’s gold rush settlements. The absence of thorough records leaves gaps in our understanding of the mining technology employed and the economic impact on the region.

While neighboring settlements have left detailed accounts of their production figures and technological innovations, Notomidula’s contribution to California’s mineral wealth remains obscured by time.

- Archival research has yet to uncover production statistics that would position Notomidula within the hierarchy of gold-producing settlements.

- The specific mining techniques—whether placer mining, hydraulic operations, or hard rock extraction—remain undocumented.

- Economic relationships between Notomidula and surrounding communities await scholarly investigation to complete the regional economic puzzle.

The Decline and Abandonment of Notomidula

Notomidula’s gradual dissolution from thriving settlement to abandoned ghost town represents a common but poignant trajectory shared by numerous California mining communities in the post-gold rush era.

By the late 1860s, multiple decline factors converged—diminishing gold yields, deteriorating ore quality, and the absence of alternative mineral discoveries prevented economic diversification.

The fragile community dynamics collapsed as the population plummeted from hundreds to fewer than fifty by 1875.

You’d have witnessed the social fabric unraveling as churches disbanded, law enforcement vanished, and the local newspaper ceased publication in 1872.

Environmental challenges and isolation from major transportation routes intensified hardships for remaining residents.

What Remains: Physical Traces and Ruins

Despite the passage of nearly 150 years since its abandonment, the skeletal remains of Notomidula persist as haunting symbols of its brief prosperity.

Like ghosts from California’s gold rush past, Notomidula’s bones whisper stories of fleeting wealth and forgotten dreams.

Today’s ruins exploration reveals only roofless structures and crumbling foundations scattered throughout Mariposa County’s remote terrain at coordinates 35°19′30″N 119°39′23″W. The site’s historical significance is evident in the partial walls and scattered brick and wood debris that once formed a thriving community.

- No intact buildings remain—only unstable walls and stone foundations mark where homes and businesses once stood

- Mining infrastructure fragments hint at Notomidula’s industrial past, with evidence of shafts and tunnels nearby

- The site remains unprotected and continues to deteriorate naturally, with no preservation efforts underway to safeguard these fragile historical remnants

Notomidula Compared to Other Sierra Nevada Ghost Towns

While the crumbling foundations and scattered debris of Notomidula tell their own story, they represent just one chapter in the Sierra Nevada’s rich tapestry of abandoned settlements.

Unlike Bodie, which boasts preserved buildings and peak populations of 8,000-10,000, or Monoville, the region’s first eastern Sierra settlement with documented historical significance, Notomidula remains largely anonymous in mining legacies.

You’ll find Notomidula conspicuously absent from most historical records, suggesting it never achieved the prominence of Cerro Gordo or Panamint.

While Bodie evolved into a protected historic park and even smaller settlements like Calico underwent partial restoration, Notomidula languished in obscurity.

Its limited documentation points to a smaller, perhaps more transient population that failed to establish the economic foothold necessary for longevity or historical preservation.

Visiting and Exploring Notomidula Today

Visitors hoping to explore Notomidula today face a challenging journey into one of Yosemite Valley’s most obscure historical sites. Unlike developed ghost towns with interpretive displays, this former Awani settlement has been reclaimed by wilderness.

Wilderness has reclaimed Notomidula, transforming this historic Awani settlement into Yosemite’s most enigmatic cultural treasure.

The cultural significance remains profound despite the absence of physical structures, representing an authentic connection to the land’s original stewards.

- Prepare for moderate to advanced hiking with navigation tools, water, and proper gear

- Obtain necessary permits through Yosemite National Park before attempting to visit

- Research Awani history beforehand, as on-site interpretation is virtually non-existent

You’ll find no signage, amenities, or obvious remnants at Notomidula. Your experience depends entirely on respectful preparation, self-sufficiency, and appreciation for subtle historical context rather than visible ruins.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Outlaws Associated With Notomidula?

You won’t find documented outlaw history or crime tales specific to Notomidula. Unlike Bodie or other prominent ghost towns, this obscure settlement lacks verified records of notable criminal activity.

What Indigenous Peoples Inhabited the Area Before Notomidula Was Established?

As ancient as the mountains themselves, the Miwok and Yokuts Native tribes inhabited the area before Notomidula’s founding. You’ll find their Historical artifacts scattered throughout the region, telling tales of their sovereign existence.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Visit or Live in Notomidula?

No famous visitors are documented in Notomidula’s sparse historical record. You won’t find evidence of historically significant figures inhabiting or passing through this obscure settlement with its minimal documented past.

Were There Any Unique Local Customs or Celebrations Specific to Notomidula?

You’d expect local festivals and traditional cuisine to define Notomidula’s character, yet history’s silence speaks volumes. No documented customs exist for this obscure settlement, unlike its more prominent neighboring boomtowns.

Did Notomidula Have Any Paranormal Legends or Ghost Stories?

While specific Notomidula ghost stories aren’t well-documented, you’d find it shares regional mining lore. Nearby ghost sightings and haunted locations reflect the broader Gold Rush paranormal traditions affecting small Sierra Nevada settlements.

References

- https://nvtami.com/2024/01/20/monoville-califoria-ghost-town/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD9M6MP6RRU

- https://patch.com/california/banning-beaumont/13-ghost-towns-explore-california

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BEdAATx3ms

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_yjBgICWl8

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aJgxAlsmnr4

- https://www.california.com/the-story-behind-the-bodie-california-ghost-town/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Foz-2R_mH8

- https://californialocal.com/localnews/statewide/ca/article/show/51711-10-california-ghost-towns-to-see/