You’ll find the ghost town of Osceola along Florida’s St. Johns River, where a bustling lumber mill community once thrived from 1916 to 1940. The Osceola Cypress Company built this company town, complete with homes, stores, and services for 200 workers and their families. While processing up to 60,000 feet of lumber daily, it became Central Florida’s leading producer. Today, only a lone brick bank vault stands as a monument to this vanished piece of Florida’s industrial past.

Key Takeaways

- Osceola began as a thriving sawmill town in 1916, established by the Osceola Cypress Company along the St. Johns River in Seminole County.

- The town supported 200 workers and their families with homes, a doctor’s office, commissary store, school, and barber shop.

- During the 1920s, Osceola was Central Florida’s leading lumber producer, processing up to 60,000 feet of lumber daily.

- Economic decline in the late 1920s forced the Osceola Cypress Company to begin dismantling operations by the 1930s.

- By 1940, the town was completely abandoned, with only a brick bank vault remaining as evidence of its existence.

The Birth of a Company Town

When the Osceola Cypress Company established its sawmill town in 1916, they strategically chose a 350-acre site in Seminole County along the St. Johns River.

You’ll find it fascinating that this location wasn’t random – it had served as King Philip’s town during the Second Seminole War.

The company’s town governance created a self-contained community with everything workers needed: homes, a doctor’s office, commissary store, school, and even a barber shop.

The Florida East Coast Railway’s proximity proved essential for transporting cypress logs to the bustling sawmill, which employed 200 workers.

The area was previously known as Cook’s Ferry before the railroad arrived in 1911.

The community was remarkably modern for its time, with its own electricity generated from the mill operations.

The community culture centered entirely around lumber production, making Osceola a classic example of how company towns shaped Florida’s industrial landscape in the early 20th century.

Life in the Lumber Mill Community

You’d find Osceola’s lumber mill workers starting their shifts at dawn, operating massive steam-powered saws that could process up to 60,000 board feet daily in hazardous conditions.

The town’s 200 daily workers faced constant risks from dangerous equipment while maintaining the skilled precision needed to run the planers and saws efficiently. By 1880, Florida had grown to include 135 sawmills operating across the state, showing the industry’s rapid expansion.

Mill life extended beyond work hours through company-provided housing and community support systems, where families shared resources and helped each other navigate the physical and economic challenges of mill work. The workers processed various wood types including cedar and cypress to produce timber, shingles, and construction materials.

Daily Worker Routines

Life in Osceola’s lumber mill community revolved around the distinctive sound of the town whistle, which regulated every aspect of daily routines. You’d start your day at the whistle’s wake-up call, knowing you’d face grueling worker schedules filled with repetitive tasks like sorting and stacking heavy lumber. The Hispanic workforce created a tight-knit community atmosphere that helped workers cope with the demanding conditions.

Throughout your eight-hour shift, you’d battle physical exhaustion and mental fatigue while handling custom orders and maintaining steady production flow. Your daily struggles included managing the monotony through daydreaming and developing personal strategies to cope with the demanding physical labor. Workers would spend considerable time cleaning and removing sawdust for bedding that local horse owners would collect.

When the workday ended, you’d return home knowing the mill’s control extended beyond work hours – they’d remind you of curfew by blinking the town’s electricity at 10 p.m., followed by a complete blackout until morning’s whistle signaled another day.

Mill Operations and Safety

Beyond the structured routines controlled by the town whistle, the Osceola Cypress Company‘s mill operations presented a complex web of industrial activity and hazards.

You’d find yourself maneuvering a workspace where safety protocols were nearly non-existent, and machinery hazards lurked around every corner.

The mill’s daily operations involved:

- Steam-powered skidders pulling massive cypress logs from swampland, with ever-present risks of burns and crushing injuries.

- Continuous saw operations processing up to 60,000 feet of lumber daily, exposing workers to blade injuries and respiratory hazards from sawdust.

- Transportation networks of mule-drawn carts and steam locomotives moving timber across uneven tram roads, creating constant accident risks.

The all-electric sawmill operations represented a significant technological advancement for the region, though safety concerns remained paramount.

If you’d worked there, you’d have relied mostly on experience and fellow workers’ support to stay safe, as formal safety measures weren’t part of early 1920s mill culture.

Workers faced demanding conditions while maintaining a production schedule of 150,000 feet of timber per day across multiple mills.

Community Support Systems

While the Osceola Cypress Company’s mill dominated the town’s economic landscape, a robust network of community support systems emerged to sustain the workers and their families.

You’d find informal networks of labor-sharing among families, with members working both in the mill and tending to agricultural pursuits like the 250-tree citrus groves. Community resilience showed through multi-building household compounds, where extended families lived and worked together, including separate “Bachelor’s Quarters” for grown sons. The Cadman citrus packing established around 1890 provided additional economic opportunities for local families.

The town’s support structure included practical innovations like elevated walkways connecting kitchens to main houses, protecting families from fire risks. Local banks provided financial services, while barter systems and trade networks helped residents weather economic fluctuations.

These interconnected support systems created a self-reliant community that thrived until the mill’s closure in the late 1930s.

Railroad’s Role in Town Development

As the South Florida Railroad arrived in 1885, Osceola County experienced a transformative period that reshaped its communities and economic landscape. The railroad’s significance became evident as it replaced traditional river transport, connecting Kissimmee to broader markets and establishing new settlement patterns throughout the region.

As this transformation unfolded, several small towns emerged, one of which was Ona, Florida, known today as a ghost town. The history of Ona, Florida ghost town showcases the fleeting nature of prosperity and the impact of economic shifts on small communities. Once a bustling hub due to railroad access, Ona gradually faded into obscurity as transportation routes evolved and businesses closed down.

The railroad’s arrival in 1885 revolutionized Osceola County, transforming transportation networks and creating new opportunities for growth and commerce.

You’ll find the railroad’s impact manifested in three key ways:

- Towns like Kissimmee emerged around railroad depots, which served as focal points for community growth.

- The Florida Midland Railroad’s east-west routes created essential connections between communities like Longwood, Palm Springs, and Apopka.

- Rail access determined the success or failure of settlements, with Kissimmee’s position as a rail hub securing its role as county seat.

This transportation revolution attracted businesses, residents, and visitors, fundamentally altering the county’s development trajectory. The Florida General Assembly approved the Florida Midland Railroad’s charter on February 10, 1885, marking a pivotal moment in Central Florida’s rail development.

Daily Operations and Services

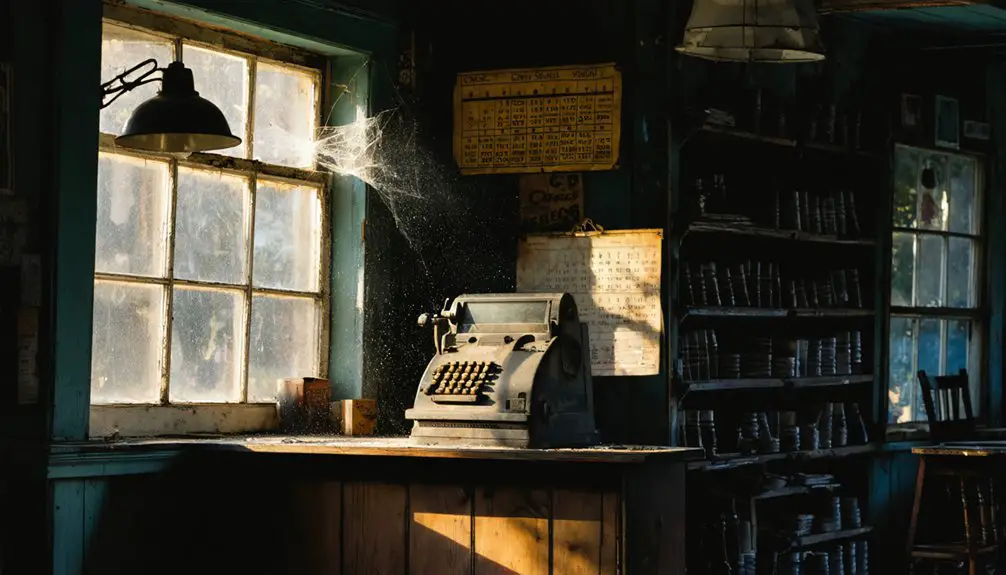

During its peak operation, Osceola functioned as a self-contained company town spanning 350 acres, where the Osceola Cypress Company provided extensive services for its 200 workers and their families.

You’d find essential worker amenities throughout the town, including a commissary store for daily supplies, a barber shop, and a post office for maintaining connections with the outside world.

Community health was a priority, with a doctor’s office providing medical care for work-related injuries and general healthcare needs.

The town’s educational needs were met through a local school, while a boarding house accommodated single and temporary workers.

The company office building served as the administrative hub, coordinating these various services that kept the tight-knit community functioning smoothly during the cypress logging operation’s heyday.

The Economic Engine of Cypress Wood

You’ll find Osceola’s cypress mill operations were remarkably productive, processing 60,000 feet of lumber daily with a workforce of 200 skilled laborers at its peak.

Through extensive trade networks, the Osceola Cypress Company distributed its highly valued, rot-resistant lumber products throughout Florida and neighboring states.

The mill’s strategic location and efficient transport systems allowed it to serve as Central Florida’s leading lumber producer during the 1920s, capitalizing on the region’s rich old-growth cypress resources.

Mill Operations and Output

When the Osceola Cypress Company built its sawmill in 1916, they established what would become Central Florida’s most productive lumber operation of the 1920s.

The mill’s workforce dynamics revolved around 200 skilled workers who pushed lumber production to unprecedented levels.

You’ll find the mill’s impressive operational achievements reflected in these key metrics:

- Daily output reached 60,000 feet of lumber at peak production

- Workforce operated continuously through multiple shifts

- Railroad connections enabled efficient distribution across the region

The mill’s success transformed Osceola into a thriving company town, complete with worker housing and essential services.

This industrial powerhouse continued its operations until 1939, when economic pressures finally forced the company to begin dismantling the facility and relocating to Port Everglades.

Transport and Trade Networks

As Osceola’s cypress lumber industry flourished, an intricate network of transportation routes emerged to support the region’s booming timber trade. The Northern Tampa Railroad served as the backbone of this network, connecting production sites to Port Tampa where ships carried lumber and shingles to northeastern markets.

You’d find trade routes dramatically reducing travel times for Seminole communities, cutting 4-5 day journeys down to just 1-2 days. These economic exchanges weren’t limited to timber – trading posts facilitated deals between natives trading animal hides and bird plumes for manufactured goods like flour and iron kitchenware.

The region’s naval stores industry thrived alongside timber, with Florida producing 85% of America’s supply. This integrated network of rail, water, and land routes transformed Osceola into a crucial hub in the national timber trade.

From Boom to Abandonment

Despite its promising beginnings as a thriving lumber town, Osceola’s transformation from boom to abandonment occurred rapidly between the late 1920s and 1940. The town’s logging practices and community dynamics shifted dramatically as economic pressures mounted, leading to its ultimate demise.

- The late 1920s brought decreased lumber demand and falling sales, weakening the town’s economic foundation.

- By the late 1930s, the Osceola Cypress Company began dismantling its operations and relocating to Port Everglades.

- The final exodus came in 1940, when remaining residents departed as homes were dismantled and lumber was salvaged.

You’ll find little evidence today of the once-bustling community, save for the solitary brick bank vault standing amid what’s now the Seminole County landfill – a stark reminder of Osceola’s fleeting prosperity.

Historical Significance and Heritage

The historical significance of Osceola extends far beyond its brief existence as a lumber town, with roots tracing back to the Second Seminole War of 1837.

You’ll find this land was originally King Philip’s town, a Seminole settlement named after the renowned leader Osceola, who fought against U.S. removal efforts.

Modern-Day Ghost Town Exploration

Modern adventurers seeking to explore Osceola’s remains face unique challenges that bridge historical preservation with contemporary safety concerns.

When practicing urban exploration in this historic site, you’ll need to follow established safety protocols and secure necessary permits before venturing into the area.

For a successful exploration of Osceola’s ghost town remnants:

- Equip yourself with GPS navigation tools, sturdy footwear, and emergency communication devices

- Connect with local guides who can identify hazardous structures and provide historical context

- Document your findings through photography while adhering to “leave no trace” principles

You’ll discover that modern technology enhances your ability to explore safely while preserving the site’s historical integrity.

Remember that structural instability and wildlife encounters pose real risks, making proper preparation essential for your adventure.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Major Accidents or Deaths Occur at the Osceola Sawmill?

Like a foggy morning, historical records remain unclear. You won’t find documented evidence of major sawmill accidents or deaths, though worker safety risks were common in Florida’s timber operations around 1900.

What Happened to the Displaced Workers After the Town’s Closure?

You’ll find most workers relocated to Port Everglades with the company or sought jobs at nearby timber operations, though the economic impact forced many to migrate to larger towns in Seminole County.

Were There Any Known Native American Artifacts Found During Town Construction?

You won’t find records of Native American artifact discoveries during the town’s construction in 1916. Archaeological surveys, including a 2020 assessment, showed no evidence of prehistoric materials at this location.

Did Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness Affect the Company Town?

You won’t find significant crime statistics or town disputes in historical records – the company maintained strict oversight, and there’s no documented evidence of major lawlessness during the town’s 1916-1940 operation.

What Was the Average Wage for Osceola Cypress Company Workers?

You’d find workers earned about $1.50-$3.00 per day, based on wage history from comparable logging companies. Labor conditions and seasonal work affected pay, with skilled positions earning more than basic laborers.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osceola

- https://floridatrailblazer.com/2018/01/26/osceola-ghost-town-in-seminole-county/

- http://www.gribblenation.org/2018/03/ghost-town-tuesday-osceola-fl.html

- https://floridahistoryblog.com/cities/osceola/

- https://floridahistoryblog.com/osceola-ghost-town/

- https://theclio.com/entry/55103

- https://osceolahistory.org/the-homes-of-pioneer-village/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahAWhGjnHRs

- https://ffgs.ifas.ufl.edu/about/forests/history/

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=219936