Packwood Station, established in 1857 by Elisha Packwood, served as an essential waystation along the Butterfield Overland Mail route in Tulare County. You’ll find it was a vibrant hub providing lodging, meals, and horse exchanges for weary travelers before the catastrophic Great Flood of 1862 submerged it under 30 feet of water. This devastating event triggered economic collapse and eventual abandonment, transforming this once-thriving settlement into one of California’s forgotten ghost towns. Its buried history awaits discovery.

Key Takeaways

- Packwood Station, established in 1857 in Tulare County, became a ghost town following the catastrophic Great Flood of 1862.

- The station served as a crucial waypoint on the Butterfield Overland Mail route before its decline and abandonment.

- Economic collapse followed the flood, with failed recovery initiatives in mining and timber unable to revive the settlement.

- The ghost town illustrates how natural disasters permanently altered California’s development during the 19th century.

- Preservation efforts continue today to maintain Packwood’s historical significance as part of California’s cultural heritage.

The Founding of Packwood Station (1857)

In 1857, amid the growing need for way stations along California’s essential transportation routes, Packwood Station emerged as a significant outpost in Tulare County. Positioned strategically along the Stockton-Los Angeles Road, this waypoint stood 12 miles southeast of Visalia and 14 miles north of Tule River Station.

You’ll find that Packwood history begins with Elisha Packwood, a prosperous cattleman who recognized the potential of this fertile land. The station quickly became vital for travelers and freight transport, with brothers Charles and Isaac Putnam serving as the first station keepers.

Their operation supported the region’s budding economic development by providing essential services to stagecoach passengers and supporting local agriculture. This station significance extended beyond mere convenience—it became a lifeline for commerce and communication in early California. Like many pioneers of his era, Elisha Packwood had previously participated in the Oregon Indian War of 1855-56 before establishing his California station. The station later became an important stop for the Butterfield Overland Mail as it connected cities across America with its reliable postal service.

Life Along the Butterfield Overland Mail Route

The Packwood Station soon found itself integrated into a larger, more ambitious system of westward communication when the Butterfield Overland Mail began operations in 1858.

As a crucial stop along one of America’s most important stagecoach routes, Packwood offered you respite from the grueling journey that carried passengers and mail nearly 2,800 miles between eastern states and California. The stagecoaches traveled along what became known as the Oxbow Route due to its distinctive curved shape on maps.

At Packwood and similar stations along the route, you’d experience:

- The frantic exchange of horses every 10-20 miles, ensuring your stagecoach maintained its relentless pace

- Brief meals of variable quality while station operators prepared fresh teams

- Encounters with diverse travelers, creating temporary communities in the wilderness

- The anxious wait for mail connecting you with distant loved ones

Passenger experiences varied dramatically, from awe at crossing vast deserts to fear during Native American conflicts. The journey was notoriously uncomfortable, with travelers enduring crowded conditions in carriages that offered little relief from the elements.

Elisha Packwood: The Cattleman Behind the Settlement

Visionary cattleman Elisha Packwood II established himself as the driving force behind what would eventually become Packwood Station. Born in Virginia, he migrated west in 1846, striking gold in California that funded his ambitious cattle enterprise.

By 1853, he’d registered the second cattle brand in Tulare County, cementing the Packwood heritage in regional agriculture.

Between 1850-1854, you’d have found Packwood transforming his 3,000-acre holdings into a prosperous Durham cattle operation. His station, situated 12 miles east of Visalia, became a crucial transportation hub intertwined with his ranching empire. From 1858 to 1861, the property served as a key stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail route connecting California with the eastern states. He appointed Royal Porter Putnam to manage the station for a monthly salary of $30.

The settlement flourished until the catastrophic 1862 flood destroyed his $40,000 fortune, burying fertile lands under sand. Packwood subsequently fled to Oregon, but his pioneering legacy in cattle branding and regional development endures through historical markers and family descendants.

Daily Operations at a 19th Century Stagecoach Stop

You’ll find Packwood’s stagecoach stop operated with clockwork precision, offering weary travelers modest accommodations in bunkhouses while maintaining strict twenty-minute turnarounds for mail deliveries.

Staff duties were clearly delineated between stable hands who swapped fresh horse teams, drivers who adhered to punishing schedules, and station managers who coordinated passenger needs and mail transfers.

Within this bustling waypoint, passengers sheltered from the elements as mail pouches changed hands under the watchful eye of staff who understood delays meant financial penalties and compromised service across the entire route. The establishment’s history traces back to 1868 when it served as a crucial relay station for both passengers and mail until the early 1900s. George C. Morrow was renowned for his night route from Anaheim to San Juan Capistrano, making necessary horse changes at strategic stations to maintain his schedule.

Passenger Accommodations

While journeying through the American frontier, weary travelers found respite in Packwood’s stagecoach stop, where accommodations reflected the practical necessities of 19th-century travel.

Sixteen to seventeen compact bedrooms housed those seeking shelter from dusty trails, while back-to-back fireplaces warmed both the parlor and dining areas where you’d gather with fellow adventurers.

The modest traveler comfort at Packwood included:

- Oil lamp lighting casting amber hues across leather-upholstered furnishings

- Coal-burning fireplaces offering warmth against frontier nights

- Family and traveler wings separated for appropriate social arrangements

- Dining services providing sustenance before the next leg of journey

Despite lacking modern amenities like running water, these stagecoach accommodations provided essential comforts at roughly $16 per fare—a reflection of frontier ingenuity where freedom and practicality converged. Travelers would marvel at the craftsmanship of the nine-passenger Concord-style stagecoaches that delivered them to these outposts. Originally constructed with high-quality redwood lumber at a cost of $7,000, the building’s durability ensured travelers could rely on its shelter for decades.

Mail Transport Logistics

At the heart of Packwood’s frontier operations lay an intricate mail transport system where precision timing and methodical handling guaranteed communication flowed across the expanding nation.

You’d witness station staff executing rapid mail sorting during the brief 20-minute stops, meticulously checking manifests while sealed bags were transferred between coaches.

Horse management defined Packwood’s reputation for reliability. Fresh teams stood ready every 10-20 miles, specially trained for endurance across California’s challenging terrain.

Stationmasters inspected leather straps and wheels nightly, verifying mechanical readiness for the next day’s journey.

Armed guards protected valuable shipments through lawless territories surrounding Packwood, with telegraph coordination alerting neighboring stations of potential delays.

This clockwork efficiency assured your letter would travel the 2,800-mile transcontinental route within the contracted 25 days.

Staff Duties

Beyond the dusty façade of Packwood’s stagecoach stations operated a precisely orchestrated system of staff duties that maintained the frontier’s lifeline.

Staff responsibilities extended around the clock, with relay station personnel executing horse exchanges in minutes while maintaining facilities for weary travelers. Daily routines demanded exacting coordination between drivers, hostlers, station keepers, and guards to guarantee schedules remained intact.

- Station operators managed the 24-hour cycle of arrivals and departures, guaranteeing meals and minimal rest accommodations remained available despite the constant flow.

- Hostlers prepared fresh horse teams every 10-20 miles, conducting exchanges with military precision.

- Guards maintained constant vigilance throughout night journeys, their compensation tied directly to the safe delivery of valuables.

- Innkeepers worked in partnership with stage lines, organizing meals within the strict 20-40 minute stopover windows.

The Devastating Great Flood of 1862

The devastating Great Flood of 1862 transformed the California landscape into an apocalyptic inland sea, beginning with a punishing Sierra Nevada snowstorm in early December 1861 that deposited up to 15 feet of snow.

For 43 relentless days, warm atmospheric rivers delivered torrential rainfall, melting the massive snowpack and turning rivers into raging torrents.

You’d barely recognize Packwood amid the flood impacts – submerged under water depths reaching 30 feet in parts of the Valley.

Communities around Packwood faced complete devastation; nearby towns like Empire City and Mokelumne City vanished entirely.

Entire settlements near Packwood disappeared forever, erased from maps and memory by the merciless floodwaters.

Despite unprecedented destruction, community resilience emerged as survivors navigated the inland seas by boat for months, rebuilding from the catastrophe that bankrupted the entire state and claimed approximately 4,000 lives.

From Prosperity to Ruin: Economic Aftermath

You’d scarcely recognize Packwood after the 1862 flood’s financial decimation, as businesses shuttered and banks foreclosed on properties once valued at record highs.

Recovery attempts through small-scale mining operations and renewed timber harvesting proved futile against the compounding effects of depleted resources and infrastructure damage.

The town’s collapse sent economic tremors throughout the region, disrupting supply chains and commercial networks that had previously connected Packwood to larger market centers.

Total Financial Devastation

While Packwood once thrived as a bustling economic center fueled by abundant natural resources, its descent into financial ruin followed a predictable pattern seen across California’s ghost towns.

The town’s failure to implement sustainable resource management led to a complete economic collapse as forests vanished and mines emptied.

You’ll notice four distinct phases that defined Packwood’s financial devastation:

- Resource depletion without renewal strategies, undermining economic sustainability

- Infrastructure deterioration as services became financially unviable

- Market volatility that crushed local industries dependent on commodity prices

- Mass exodus of skilled workers, creating a downward spiral of decreased spending

What remained was a shell of former prosperity—abandoned buildings standing as silent monuments to short-term profit prioritized over long-term community survival.

Failed Recovery Attempts

Facing the stark reality of economic collapse, Packwood’s community launched multiple recovery initiatives that ultimately faltered against overwhelming obstacles.

Their failed revitalization efforts encountered crippling structural problems: deteriorating buildings required prohibitive restoration costs, while crumbling infrastructure deterred potential investors.

You’d have witnessed financial constraints at every turn. Banks refused loans, citing minimal returns, while the dwindling tax base couldn’t support essential services.

When entrepreneurs attempted to establish new businesses, they faced insurmountable startup costs amid a shrinking market.

Community disengagement accelerated as younger residents fled, leaving an aging population with diminishing capacity for economic renewal.

Environmental contamination from former mining operations created regulatory hurdles that further complicated recovery plans.

Without sufficient capital, infrastructure, or human resources, Packwood’s attempts to reinvent itself repeatedly collapsed under the weight of these compounding challenges.

Regional Economic Ripples

Packwood’s economic collapse radiated far beyond its own borders, creating shockwaves that destabilized the entire regional economy. The town’s demise revealed the fragile economic interdependence that once sustained nearby communities.

As Packwood’s mines closed, neighboring settlements lost crucial commerce connections, trade routes shifted, and transportation networks withered.

You’ll recognize the regional decline through:

- Abandoned railroad spurs that once connected Packwood to thriving market centers

- Former supply towns now struggling with their own population exodus

- Consolidated school districts spanning ever-widening geographic areas

- Agricultural operations that lost immediate markets for their goods

What you’re witnessing isn’t just one town’s failure but the collapse of an intricate economic ecosystem that once flourished around the mining industry’s gravitational pull.

Packwood’s Journey North to Oregon

In April of 1850, as conflicts with Native American tribes intensified along the Southern Oregon and California coast, William H. Packwood was dispatched northward on a vessel commanded by Captain McArthur.

Initially stationed at Vancouver, Oregon, he’d soon relocate frequently between regional outposts.

Packwood’s motivations weren’t solely military—he’d lost his California fortune of $40,000 and nearly his life, compelling him to seek renewal in Oregon’s frontier.

You’ll find his story emblematic of countless settlers who navigated Oregon’s challenges during this tumultuous period.

After his 1852 discharge, he embraced the region’s economic opportunities through mining, packing, and cattle ranching along the south coast, laying groundwork for his later eastern Oregon ventures that would establish Auburn and other boomtowns.

Lost to Time: The Search for Packwood’s Remains

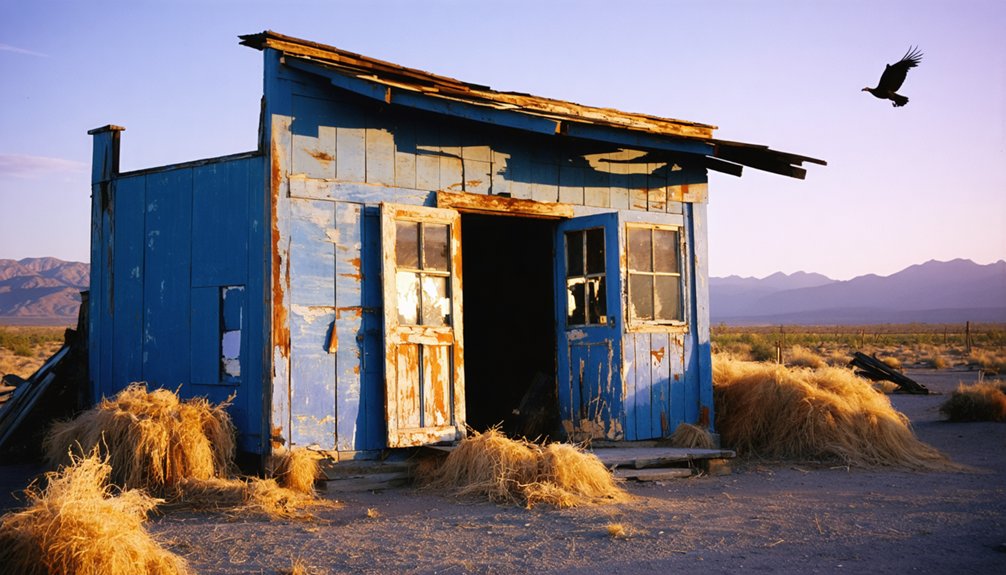

While William Packwood established his legacy across Oregon’s frontier, the physical remnants of Packwood Station in California have vanished almost completely from both landscape and memory.

You’ll find no standing structures, commemorative plaques, or obvious ruins marking this once-vital waypoint in Tulare County’s transportation network.

The station’s historical significance persists despite its physical absence:

- Its remote Sierra Nevada foothills location represents the challenging terrain early travelers navigated.

- The site holds archaeological potential for understanding 19th-century stagecoach infrastructure.

- Its abandonment mirrors the technological shift from stage to rail transportation.

- The absence of preservation efforts highlights how easily frontier history disappears.

Amateur historians occasionally venture to the approximate location, but without coordinates or visible markers, Packwood Station remains truly lost to time.

Legacy of California’s Forgotten Waystations

Beyond the lost outpost of Packwood Station lies a greater network of forgotten California waystations that once formed the backbone of 19th-century travel infrastructure.

California’s forgotten waystations stand as silent witnesses to the pioneering networks that once connected a developing frontier state.

You’re witnessing the ghosts of an era when Pleasant Grove House and Hitchcock’s Station provided essential rest, meals, and lodging for Gold Rush travelers traversing treacherous routes.

The waystation significance extends beyond mere convenience—these were lifelines in California’s development, enabling the westward movement that shaped the state.

As railroads expanded and modern highways emerged, these important stops faded into obscurity.

Today, their remains face threats from development, vandalism, and simple neglect.

Local historical preservation efforts struggle against time and limited resources, yet these forgotten waystations represent an irreplaceable cultural legacy—physical connections to California’s pioneering spirit and the freedom of movement that defined its formative years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Artifacts From Packwood Station Recovered After the Flood?

No documented evidence exists of artifact recovery from Packwood Station after floods. You’ll find the flood impact on potential artifacts remains unrecorded in historical archives concerning this Washington location.

What Indigenous Tribes Inhabited the Area Before Packwood’s Settlement?

You’ll find the Taidnapam (Upper Cowlitz) people inhabited this area for thousands of years. Their tribal history shows deep cultural significance through sustainable fishing practices and seasonal settlements along the Cowlitz River valley.

How Did Mail Delivery Continue After Packwood Station’s Destruction?

You think Amazon delivery’s rough? After Packwood’s demise, your mail service rerouted through Visalia and Tule River stations, with delivery routes adapting to alternative stagecoach stops until railroads ultimately liberated correspondence from horse-drawn constraints.

Did Any Packwood Descendants Return to Search for the Site?

No documented evidence exists of Packwood descendants returning specifically to search the site. You won’t find records of family reunions or Packwood heritage expeditions focused on locating the former stagecoach station.

What Modern Landmarks Exist Near Packwood’s Approximate Former Location?

Dusty plains meet oak-studded foothills near you’ll find State Route 190, Tulare County Museum, Lindsay Museum, and Kaweah River—silent witnesses to Packwood’s history, with nearby attractions including Sierra Nevada foothills and agricultural landmarks.

References

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Packwood_Station

- https://thelittlehouseofhorrors.com/bodie-the-cursed-ghost-town/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZk4MJej_24

- https://maturango.org/tag/california-ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElbXVNDurPc

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/gdc/calbk/008.pdf

- https://truwe.sohs.org/files/packwood.html

- https://www.tularecountyhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Historic-markers-Sheet1-1.pdf

- https://www.lindsaymurals.org/butterfield.html