Page, California emerged as a silver mining boomtown in 1877 before rapidly declining when ore quality diminished and silver prices collapsed. You’ll find remnants of wooden structures and mining equipment scattered across this Mojave Desert ghost town. Miners once endured harsh conditions, hauling water from miles away while working in extreme temperatures. The site now attracts history enthusiasts seeking glimpses of California’s mining heritage. These weathered ruins tell stories of fortune-seekers who came and went.

Key Takeaways

- Page originated as a silver mining town in the Mojave Desert after ore was discovered on August 5, 1877.

- The town experienced a brief economic boom with saloons, supply stores, and assay offices before rapid decline.

- Daily life involved adapting to extreme desert conditions with residents hauling water from miles away.

- The collapse of silver prices in the 1890s led to an exodus, transforming Page from settlement to ghost town.

- Today, Page exists as ruins attracting tourists while facing preservation challenges from environmental factors and limited funding.

The Birth of a Desert Mining Outpost

While gold and silver discoveries sparked numerous boomtowns across California’s desert landscape in the late 1800s, Page emerged from more modest beginnings.

Unlike the frenzied rushes that defined places like Bodie or Calico, Page’s establishment followed a more deliberate path in California’s mining history.

The town’s origins remain somewhat obscured by time, with limited documentation capturing its early development.

What’s known about Page’s mining legacy suggests it was one of many small outposts that dotted the harsh desert terrain, where prospectors sought fortune amid unforgiving conditions.

You’ll find Page’s story reflects the determined spirit of frontier settlers who ventured into remote territories, creating communities where only the resilient could survive.

These desert pioneers established rudimentary infrastructure while extracting whatever minerals the surrounding geology offered, unlike the more prosperous Calico which became the largest silver mine in California during its peak.

Similar to the once-thriving town of Hornitos, Page featured original structures that provided necessary services to the surrounding mining community.

Silver Rush: The Economic Engine of Page

You’ll find a stark contrast between the fleeting wealth of Page’s miners and the harsh realities of desert prospecting during the silver boom of the late 1800s.

The silver discoveries initially transformed this remote outpost into a bustling economic hub, with assay offices, supply stores, and saloons quickly establishing themselves alongside the mines that dotted the arid landscape.

As miners extracted thousands of dollars in silver ore from the parched earth, the town’s prosperity remained precariously balanced on increasingly depleted veins, a mirage of sustainability in California’s unforgiving desert terrain. Much like the Calico district established in 1881 nearby, Page represented one of several silver mining communities that briefly flourished in California’s desert regions. The disappointing results of ore shipments, which averaged only 150 dollars per ton, contributed significantly to the eventual decline of mining operations.

Miners’ Fleeting Fortunes

When silver ore was first discovered in the canyons near what would become Page, California on August 5, 1877, few could have predicted the rapid economic transformation—and equally swift decline—that awaited the region.

The fleeting wealth of Page’s silver rush began with Purcell and Slankard’s Southern Belle claim, which sparked a mining frenzy after assays showed $60 per ton.

You would’ve witnessed savvy prospectors like Purcell selling their claims by August 1878, recognizing the transient dreams that defined mining speculation.

As silver prices plummeted and competing discoveries in Nevada and Utah flooded markets, miners abandoned Page for more promising ventures.

Unlike catastrophic ghost towns, Page’s dissolution came through calculated economic withdrawal as investors shifted to diversified portfolios rather than single-location commitments.

The town’s economy mirrored other California mining ventures like Cerro Gordo, where stock bubble bursts led to widespread economic collapse and financial ruin for investors.

After extraction at sites like Page and Cerro Gordo, silver ingots were transported via steamships across Owens Lake before continuing their journey to Los Angeles by mule train.

Desert’s Silver Mirage

As the morning sun cast long shadows across the jagged canyons in August 1877, Page emerged as California’s newest silver frontier, joining established districts like Silverado, Cerro Gordo, and Silver Mountain in the state’s mineral legacy.

You’d have witnessed the familiar pattern—initial claims quickly evolved into mining companies extracting miargyrite and pyrargyrite from limestone formations. The desert landscape transformed as investors from San Francisco poured capital into infrastructure.

Smelters rose alongside sawmills while mule trains established crucial supply lines. Like Cerro Gordo, which delivered over 2 million dollars in valuable minerals to Los Angeles in 1874 alone, Page’s economy diversified beyond silver mining, creating secondary industries for fuel and construction.

But the ghost town we see today tells the familiar tale of boom-and-bust economics—when silver prices plummeted, so did Page’s fortunes, leaving behind silent reminders of prosperity that vanished as quickly as desert rain.

Daily Life in a Mojave Boomtown

You’d have risen before dawn in Page to avoid working during the scorching midday heat, when temperatures regularly exceeded 110°F and the sun turned the mining camp into a shimmering mirage of dust and parched earth.

After completing your shift in the silver mines, you’d have trudged back to your wooden shack or canvas tent, where you might rinse away the day’s grime with precious water hauled from miles away. The mining operations required massive industrial systems that transformed these strategically positioned desert towns into bustling economic hubs.

Evenings offered brief respite in the camp’s saloons or makeshift dance halls, where miners spent hard-earned wages on whiskey, card games, and occasional traveling entertainment troupes that braved the desolate Mojave to perform in these isolated frontier communities. Unlike the now-famous Roy’s neon sign that later became a Route 66 landmark in Amboy, Page’s establishments were marked by simple wooden placards illuminated only by lantern light.

Desert Heat Survival

Life in Page, California demanded extraordinary resilience against the Mojave Desert’s punishing climate.

You’d face summer temperatures soaring beyond 100°F, with brutal 40-degree daily swings that turned scorching days into frigid nights. Desert survival meant adapting your entire existence to this harsh reality.

Heat management became your constant focus. You’d construct thick-walled adobe homes with strategic cross-ventilation and shaded porches. Your daily rhythm shifted—working at dawn and dusk, sheltering during midday infernos.

You’d don loose, light-colored clothing and ration precious water, knowing the next rainfall might be months away. The region’s annual precipitation typically ranged from just 2 to 6 inches, making every drop crucial for survival.

Community wells became lifelines during the bone-dry summers when less than 5% of the year’s meager rainfall occurred. Without these adaptations, heat exhaustion, dehydration and sunburn could quickly turn fatal.

Mining Camp Routines

Pickaxes and shovels clanged against stone before dawn, signaling the start of another grueling day in Page’s mining camps. You’d rise with the sun and labor until dusk, spending 10-14 hours working your claim six days weekly.

Your routine consisted of panning creek beds, digging tunnels, or sluicing gravel until your muscles screamed in protest.

Evening brought no luxury—just a return to your tent or makeshift cabin where you’d prepare simple meals of salt pork and bread over an open fire.

Daily schedules left little room for comfort in these desert boomtowns. You might seek solace in whiskey at a canvas saloon or letter-writing by lamplight.

Despite the harsh conditions, a grudging camaraderie formed around shared hardships, creating unwritten codes that governed life where formal law couldn’t reach.

Frontier Entertainment Options

When darkness fell over Page’s dusty streets, saloons blazed with kerosene lamps, beckoning weary miners to escape the Mojave’s harsh realities.

You’d find yourself shoulder-to-shoulder with prospectors of every stripe, the clink of glasses and boisterous laughter drowning out the desert’s silence.

The saloon culture thrived as the beating heart of Page’s social scene. Here, dusty fortunes changed hands over faro and poker tables, while dice games attracted those hoping Lady Luck might compensate for mining disappointments.

In these rough-hewn establishments, you could negotiate claims, hear the latest strike rumors, or simply lose yourself in a traveling musician’s melodies.

For special occasions, you might attend performances at makeshift theaters or join community celebrations that momentarily transformed the mining camp into something resembling civilization.

The Inevitable Decline of a Resource Town

The rise of resource towns like Page inevitably carried within it the seeds of their eventual demise. As accessible silver deposits dwindled, Page’s economic vulnerability became painfully apparent. Mining operations shifted underground, dramatically increasing extraction costs while profits shrank.

When silver prices collapsed in the 1890s, the final blow struck a community already weakened by resource depletion. You’d have witnessed the exodus firsthand—miners packing their belongings, businesses boarding up storefronts, and the post office closing its doors.

The once-bustling streets grew quiet as community resilience faltered against unstoppable market forces. Though some investors attempted revival during brief metal price surges, these efforts proved futile.

Within a decade, Page had transformed from a promising frontier settlement to another California ghost town—another reminder of fortune’s fleeting nature in the West.

What Remains: Exploring Page’s Physical Remnants

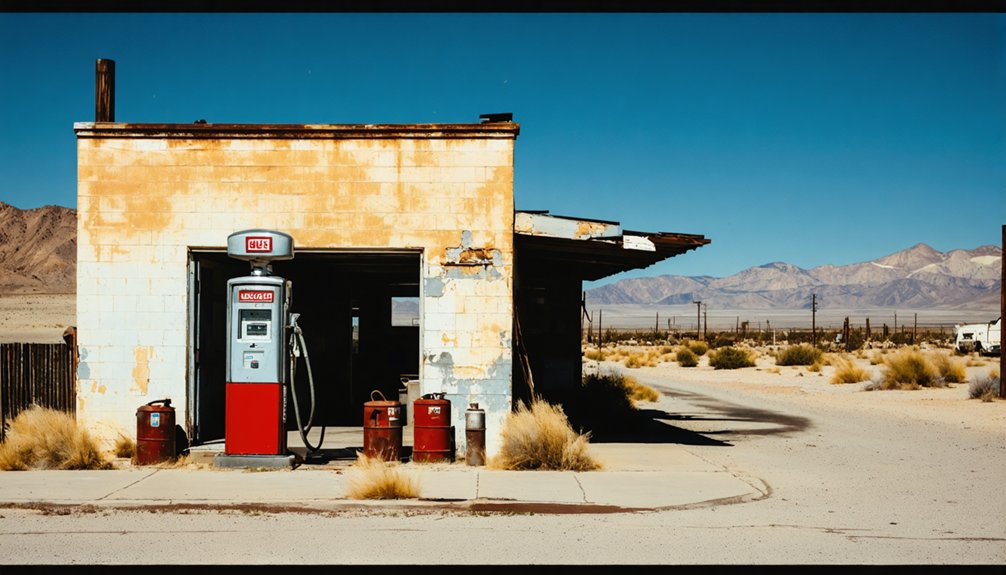

Rusty hinges and crumbling foundations are all that remain of Page, California’s brief but vibrant existence.

As you explore the site today, you’ll find physical artifacts scattered across the landscape—each telling part of Page’s forgotten story.

The historical significance of these remnants can’t be overstated; they’re the last tangible connections to this once-thriving community:

- The schoolhouse foundation stands as a silent reminder of community life

- Mining debris—picks, machinery fragments, and tailings—speak to the town’s industrial purpose

- Household items emerge after rains, offering glimpses into domestic life

- The overgrown cemetery, with its weathered markers, represents Page’s final chapter

No intact structures remain standing—just fragments slowly returning to the earth.

Maneuvering to Page requires careful preparation and desert wisdom that many casual explorers unfortunately lack.

Your vehicle should be four-wheel-drive with high clearance to tackle the unforgiving dirt roads and sandy approaches. Don’t rely solely on GPS accuracy—desert navigation demands redundancy, so carry physical maps and a compass as electronic devices often fail in these remote areas.

Desert travel requires robust vehicles and old-school navigation—electronic lifelines fail where signal fears to tread.

Plan your journey during spring or fall when temperatures are moderate, and always travel during cooler hours. You’ll need at least a gallon of water per person daily, and inform someone of your intended route and return time.

The desert’s shifting sands and sudden storms can transform familiar paths into unknown territory within hours. Bring recovery gear and extra fuel—you won’t find service stations in this forgotten corner of California.

Photography Opportunities Among the Ruins

Standing amid Page’s ghostly remnants, photographers discover a visual treasure trove that tells California’s forgotten desert history through light and shadow. The abandoned structures offer compelling compositions at any hour, though golden hour casts dramatic shadows across weathered facades.

For the most evocative images, try these photographic techniques:

- Frame shots through empty doorways or broken windows to create layers of visual storytelling

- Capture detail shots of rusting mining equipment against textured wooden walls

- Use long exposures during full moon nights for ethereal, ghostly scenes

- Position wild burros or desert flora in foreground to contextualize the ruins

The stark contrast between human-made elements and encroaching desert creates a poignant visual narrative of impermanence—a photographer’s playground where history’s textures await your unique perspective.

Nearby Ghost Towns and Mining Sites

Within a day’s drive from Page, California’s haunted remnants, you’ll find a constellation of ghost towns and mining sites that tell the broader story of the state’s boom-and-bust resource extraction history.

Your ghost town exploration might lead you to Bodie State Historic Park, where 200 buildings stand frozen in time after yielding $38 million in precious metals during its heyday.

Walk Bodie’s silent streets among 200 weather-beaten structures, where mining fortunes worth millions were once made and lost.

For serious mining heritage enthusiasts, Empire Mine‘s 367-mile underground network offers a glimpse into industrial-scale gold extraction that produced 5.6 million ounces.

Meanwhile, Ballarat in Death Valley presents adobe ruins where 500 residents once supported seven saloons.

Don’t miss Malakoff Diggins, where hydraulic mining carved a 600-foot canyon before environmental laws ended the practice in 1884.

Each site preserves California’s raw pioneering spirit in weathered wood and rusted metal.

Preservation Challenges and Future Prospects

The ghosts of Page’s past face a constant battle against time and the elements, presenting preservationists with formidable challenges that extend well beyond mere maintenance. The “arrested decay” preservation techniques employed mirror those at Bodie, where structures remain authentically weathered while preventing complete collapse.

You’ll find these critical challenges threatening Page’s historical integrity:

- Harsh Sierra Nevada weather conditions accelerate wooden structure deterioration

- Limited funding strategies rely heavily on visitor fees and foundation donations

- Remote location complicates transportation of materials and preservation crews

- Balancing authentic decay with necessary stabilization requires specialized expertise

Without commercial infrastructure, preservationists must continually innovate funding strategies.

The future of Page depends on sustainable preservation approaches that respect its historical character while ensuring these fragile remnants of California’s mining era survive for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal Legends Associated With Page?

You’ll find limited documented ghostly sightings in Page, though locals mention strange phenomena near abandoned mining structures. These potentially haunted locations haven’t been thoroughly investigated by paranormal researchers exploring California’s forgotten towns.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Visit Page?

Like a desert mirage, Page’s famous visitors were limited to Western film stars during its 1946-1950s heyday. You won’t find gold rush millionaires or politicians in its brief historical significance.

What Happened to the Residents When the Town Declined?

When economic decline hit, you’d have witnessed families packing their belongings, abandoning homes for greater opportunities elsewhere. Your neighbors scattered gradually through resident migration, seeking livelihood where mining and commerce still thrived.

Were There Any Major Crimes or Violence in Page?

You’ll find no significant crime incidents or violence history in Page’s records. The town’s isolation and small population meant disputes rarely escalated beyond minor altercations among miners.

Did Page Have Any Unique Cultural Traditions or Celebrations?

You won’t find documented cultural festivals unique to Page. Like many small California mining settlements, they likely celebrated Independence Day with community gatherings featuring local music, dancing, and shared meals under desert skies.

References

- https://whimsysoul.com/must-see-california-ghost-towns-explore-forgotten-histories/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Foz-2R_mH8

- https://www.californist.com/articles/interesting-california-ghost-towns

- https://capitolmuseum.ca.gov/state-symbols/silver-rush-ghost-town-calico/

- https://parks.sbcounty.gov/park/calico-ghost-town-regional-park/

- https://www.visitcalifornia.com/road-trips/ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.bodie.com

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8tch1uEfrJs

- https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/historyculture/death-valley-ghost-towns.htm