Paloma flourished as a Gold Rush town after J. Alexander’s 1851 quartz discovery revolutionized local mining. When Senator William Gwin purchased the operation in 1867, he transformed it into one of California’s richest mines until its 1908 closure. Known officially as “Fosteria” for postal services, this California Historical Landmark (#295) now exists as scattered ruins along historic mining routes. The weathered remains of stamp mills and cabins tell a deeper story of boom-and-bust cycles.

Key Takeaways

- Paloma originated in 1849 with placer mining and became one of California’s richest quartz operations under Senator William Gwin’s ownership.

- Known dually as “Paloma (Fosteria)” on California Historical Landmark #295, the town experienced its golden age in the 1860s-1870s.

- Mining operations ceased in 1908, transforming the once-thriving mining community into a ghost town.

- Visitors can explore weathered remains of stamp mills, abandoned mines, stone walls, and rusted machinery partially reclaimed by nature.

- Paloma sits along historic mining routes connecting Gold Rush communities, offering photography opportunities and insights into California’s mining heritage.

The Rise and Fall of Paloma: A Mining Town’s Legacy

While many California ghost towns share similar stories of boom and bust, Paloma’s journey through history offers a particularly vivid illustration of the gold rush era‘s transformative power.

You’ll find its origins in 1849, when placer mining began before J. Alexander’s 1851 quartz discovery revolutionized local mining technology. Similar to how James Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, triggering widespread migration to California’s mining regions. When Senator William M. Gwin acquired the property that same year, he established what would become the town’s economic centerpiece.

The 1860s and 1870s marked Paloma’s golden age, with advanced water infrastructure supporting massive extraction operations. Before its closure, the Gwin Mine had yielded millions in gold, contributing significantly to California’s economy.

Ghost town dynamics emerged after 1908 when mining operations ceased completely, triggering population decline and economic collapse.

Today, Paloma stands as California Historical Landmark #295, a silent representation of the volatile nature of resource-dependent communities.

The Paloma Mine: Engine of a Forgotten Community

At the heart of Paloma’s brief but vibrant history stood the Paloma Mine, a gold-producing powerhouse that transformed a remote area of Calaveras County into a thriving community.

Originally discovered by J. Alexander in 1851, the operation evolved from simple placer mining to sophisticated quartz extraction under William M. Gwin’s ownership.

The mine’s impact on Paloma’s development can’t be overstated:

- Advanced mining technology progressed from individual prospecting to large-scale operations

- Water supply infrastructure included the Sandy Gulch and Kadish Ditches from the Mokelumne River

- Custom stamp mills revolutionized local ore processing capabilities

- Economic sustainability depended entirely on the mine’s continued production

Senator Gwin purchased the mine in 1867 and renamed it after himself, making the Gwin Mine one of California’s richest quartz operations.

Like many towns in the region, Paloma’s establishment followed the pattern of communities that formed around major strikes throughout Calaveras County.

When the mine finally closed in 1908, Paloma’s fate was sealed.

The economic backbone vanished, and the once-thriving town faded into history.

Senator Gwin and the Renaming of Paloma’s Fortune

The transformation of Paloma’s fortunes can be traced to one influential figure who left an indelible mark on both California politics and the town’s mining operations.

William McKendree Gwin, California’s first U.S. Senator, arrived in San Francisco during the 1849 Gold Rush and quickly established himself in the state’s political landscape.

After being elected as a delegate to California’s constitutional convention, Gwin displayed his political acumen despite irritating some fellow delegates with his haughty demeanor.

In 1867, Gwin’s influence extended beyond politics when he purchased the Paloma Mine. He promptly renamed it the Gwin Mine, forever changing the town’s identity.

Under his ownership, the mine generated millions in gold until its closure in 1908, cementing Gwin’s mining legacy throughout Calaveras County. Today, Paloma is recognized as California Historical Landmark No. 295 for its significant contribution to the state’s mining heritage. This rebranding symbolized more than a mere change in ownership—it represented the direct connection between political power and mining wealth that characterized California’s formative years.

Daily Life in a Sierra Nevada Mining Settlement

Living conditions in Paloma mirrored those of many Sierra Nevada mining settlements, where survival demanded both resilience and adaptability from residents.

You’d have spent your days in grueling 10-12 hour shifts at the mine before returning to simple wooden cabins or communal lodgings. Daily routines centered around basic necessities – preparing meals of beans, bacon and occasional game over open fires. Similar to Valley Springs residents, many people relied on limited water sources for their daily needs. Miners often participated in cooperative efforts to maximize efficiency as mining evolved beyond individual panning.

- Limited medical care meant minor injuries could become life-threatening

- Social interactions happened primarily in saloons and gambling halls

- Community gatherings during holidays provided rare moments of unity

- Seasonal work patterns followed weather conditions, with winters bringing slower periods

Despite hardships, residents formed tight bonds through shared experiences, creating a frontier community that balanced harsh realities with determination to prosper in California’s gold country.

Postal Service and Communication in Isolated Paloma

Three major challenges defined postal service in isolated Paloma during the California gold rush era, creating a complex system of communication unlike anything settlers had experienced back East.

First, Paloma couldn’t even use its own name for postal purposes due to duplication elsewhere in California, forcing residents to receive mail through the “Fosteria” post office instead.

Second, you’d pay premium rates for communication – a dollar per letter via pony express routes that connected Paloma to distribution centers like Coloma, which processed over 4,000 pieces of mail monthly by 1854.

Third, delivery remained unreliable due to hostile terrain, weather, and inconsistent carriers. Much like Chorpenning’s routes elsewhere in California, carriers often had to redirect mail to avoid snow in mountains during winter months. By 1850, Coloma had established a post office along with various mercantile stores and hotels to support the booming population.

Despite these postal challenges, communication methods evolved quickly, with semi-monthly deliveries becoming standard and overland routes supplementing the primary Panama isthmus steamship connection to the Atlantic states.

From Paloma to Fosteria: A Town’s Identity Shift

While most California mining towns maintained consistent identities throughout their existence, Paloma experienced a unique dual identity crisis that shaped its historical legacy. When establishing a post office, residents discovered “Paloma” was already taken elsewhere in California. The town adopted “Fosteria” to honor Benjamin Franklin Foster, the original landowner, creating a name significance that reflected the area’s pioneering family.

- You’ll find Fosteria referenced in all official records from 1903-1918

- The Foster family’s legacy became embedded in the town’s very identity

- U.S. Geological Survey maps from the period exclusively label the settlement as Fosteria

- The dual identity is preserved on California Historical Landmark No. 295 as “Paloma (Fosteria)”

After the mine closed in 1918, the name gradually reverted to the original Paloma in historical references.

Ghost Town Tourism in California’s Gold Country

When you visit Paloma today, you’ll find it situated along historic mining routes that once connected bustling Gold Rush communities but now serve as scenic byways for ghost town enthusiasts.

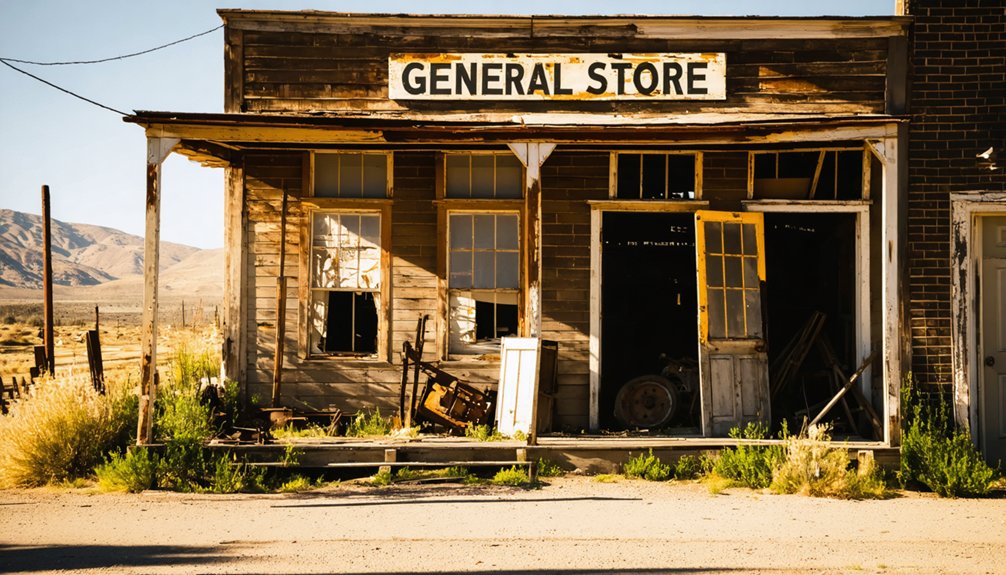

The weathered remains of stamp mills and abandoned mine entrances create striking photography opportunities, particularly during the golden hour when sunlight casts dramatic shadows across deteriorating structures.

Amateur and professional photographers frequently capture the town’s mining artifacts, wildflower-dotted landscapes, and the distinctive play of light on aged wood and rusted metal that tells Paloma’s silent story.

Historical Mining Routes

How did the intricate web of trails connecting California’s Gold Country shape the destiny of towns like Paloma?

These routes, originally primitive dirt paths navigable by foot or pack animal, became Paloma’s lifeline to the booming gold economy. You’ll find these historical navigation corridors followed natural waterways essential for mining operations.

- Routes connected Paloma to major supply points and emerging settlements throughout Calaveras County

- Miners relied on terrain landmarks to traverse the rugged Sierra Nevada landscape

- Remnants of mining infrastructure dot these paths, revealing the town’s economic backbone

- Many trails linked to larger networks used by Forty-Niners traveling from Independence, Missouri

Today, these preserved routes offer you a tangible connection to Gold Rush history as you explore Paloma’s ghostly remains.

Photography Hotspots

Capturing the fading glory of Paloma’s past requires knowing exactly where to point your lens. For dramatic compositions, head to the elevated hillside behind Main Street where you’ll frame the entire townscape against the Sierra foothills. The weathered facades of the old saloon, post office, and general store offer ideal subjects for wide-angle photography techniques that emphasize architectural decay.

Don’t miss the interior of the schoolhouse where light streams through broken windows, creating perfect conditions for moody black-and-white shots. Historic artifacts like rusted mining tools and abandoned furniture tell compelling visual stories when photographed in close-up detail.

For unique perspectives, visit at sunrise when golden light washes across the eastern-facing storefronts, or capture the cemetery at dusk when long shadows accentuate the weathered headstones. Remember, some buildings have restricted access, so check preservation rules beforehand.

Architectural Remains and Physical Evidence

Despite the passage of time, Paloma’s architectural footprint reveals itself through scattered remnants that dot the landscape today.

The ghost town exploration experience offers glimpses into California’s mining era through structures that have weathered decades of abandonment.

While specific documentation of Paloma’s remains is limited, visitors searching for architectural significance might find:

- Foundation outlines of the former mining operations and processing facilities

- Weathered wooden structural elements that once framed miners’ cabins

- Stone walls and chimneys standing as solitary sentinels amid the brush

- Rusted machinery fragments partially reclaimed by the surrounding landscape

These physical traces serve as tangible connections to California’s gold rush heritage, allowing you to piece together the daily lives of those who sought fortune in this now-silent settlement.

Paloma’s Place in California Historical Landmarks

When you visit Paloma today, you’ll find it proudly designated as California Historical Landmark #295, officially recognizing its significant contribution to the state’s gold rush heritage.

This landmark status, established to preserve the memory of Paloma’s rich mining history, acknowledges both Senator William McKendree Gwin’s development of the area and the town’s emergence during the pivotal 1848-1849 gold rush period.

The preservation framework guarantees that despite its ghost town status, Paloma’s historical importance remains accessible for research, education, and public engagement with California’s mining legacy.

LANDMARK DESIGNATION SIGNIFICANCE

As California Historical Landmark No. 295, Paloma holds a distinguished position within the state’s official roster of historically significant sites. This designation acknowledges the town’s contributions to California’s mining heritage and broader Gold Rush narrative.

The landmark benefits extend beyond mere recognition, creating opportunities for historical education and preservation.

When you visit Paloma, you’ll find it’s part of a thorough network that:

- Connects diverse Gold Rush communities across California’s historic landscape

- Preserves the authentic story of small mining settlements

- Provides tangible links to 19th-century mining technology and community development

- Supports potential funding for ongoing preservation efforts

This official recognition guarantees Paloma’s mining legacy remains accessible for generations, offering a window into California’s transformative economic period.

PRESERVING MINING HERITAGE

While countless California gold rush towns faded into history, Paloma stands as a symbol of the state’s commitment to preserving its mining heritage. As California Historical Landmark #295, you’ll find recognition of the area’s pivotal role in mining technology evolution, from simple placer operations to advanced quartz extraction methods.

The Calaveras Heritage Council maintains detailed documentation of Paloma’s shift from early mining camp to established community. You can explore the remaining structures that survived the post-mining exodus, offering glimpses into 19th-century industrial practices.

The environmental impact of these operations remains visible in tailing piles and transformed landscapes, serving as both cautionary tale and proof of human ingenuity. These physical remnants provide tangible connections to California’s formative gold rush era that shaped the state’s identity and economy.

Geotourism and Heritage Preservation Efforts

Despite its diminished presence on California’s modern landscape, Paloma stands as a tribute to the state’s rich mining heritage through ongoing geotourism and preservation initiatives.

As California Historical Landmark #295, Paloma attracts history enthusiasts seeking authentic connections to Gold Country’s past, though geotourism impact remains modest compared to other ghost towns.

When you visit, you’ll find:

- Self-guided exploration opportunities of historic mine sites

- Regional heritage trails featuring Paloma’s gold mining story

- Educational signage and historical markers, though limited

- Community-led preservation efforts working against time

Preservation challenges include Paloma’s remote location, limited funding, and the continuous battle against structural deterioration.

Local historical societies conduct research and occasional clean-up events, but without sustained resources, these fragile remnants of California’s mining era remain at risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Remaining Residents Living in Paloma Today?

Like a small flickering flame, Paloma has current population presence with families maintaining households. You’ll find 2.72 residents per household, with children comprising 13.4%, though local preservation efforts require more documentation.

What Natural Disasters or Events Contributed to Paloma’s Abandonment?

You’d find that periodic flooding after hydraulic mining damaged Paloma’s infrastructure, with the 1862 flood’s aftermath being particularly devastating. No major earthquake damage contributed directly to the town’s abandonment.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness in Paloma?

You’ll find little documented crime history in Paloma specifically. Unlike nearby towns with notorious outlaws, Paloma lacked significant lawlessness requiring formal law enforcement, despite the region’s reputation for frontier violence.

What Indigenous Peoples Inhabited the Paloma Area Before Mining Began?

Imagine a landscape once alive with Native tribes! You’d find Me-Wuk (Miwok) peoples stewarding this region before mining began, maintaining deep cultural heritage connections to the land through generations.

Are There Any Haunting Legends or Supernatural Stories About Paloma?

You’ll find few documented spectral sightings in Paloma itself. Instead, ghostly encounters are more prevalent in nearby Coloma, particularly at the Vineyard House where former residents reportedly still linger.

References

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ca-coloma/

- https://www.historynet.com/ghost-town-coloma-california/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wGN1mmS3FBA

- https://www.californiahauntedhouses.com/real-haunt/vineyard-house.html

- https://evendo.com/locations/california/central-california/landmark/paloma-california-historical-landmark-no-295

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paloma

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ma8Sd6GXw0

- https://sierranevadageotourism.org/entries/paloma-no-295-california-historical-landmark/66e0dd49-7cb4-46dd-a747-e2293e1ba837

- https://www.calaverashistory.org/paloma

- https://ohp.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=21392