Pinacate was a gold mining town established in 1882 near Perris, California, along the California Southern Railroad. The settlement boomed after the Good Hope vein discovery, which produced 104,000 ounces of gold until 1959. You’ll find ruins of foundations and mining equipment scattered across the desert landscape today. No amenities exist on-site, so bring water and use high-clearance vehicles. The abandoned mines and untouched landscape tell a deeper story of boom-and-bust frontier economics.

Key Takeaways

- Pinacate was established in 1882 along the California Southern Railroad and flourished as a gold mining town until its decline around 1903.

- The Good Hope Mine was the area’s most productive, yielding 104,000 ounces of gold and accounting for nearly one-third of Southern California’s total gold production.

- The community consisted of diverse ethnic groups including Anglo-Americans, Mexicans, and Chinese residents who formed bonds through shared hardships.

- Mining operations reached depths of 575 feet before water flooding problems contributed to the town’s economic decline and eventual abandonment.

- Today, visitors can explore Pinacate’s authentic ruins and mining remnants but should prepare for rough terrain with no amenities available on-site.

The Lost Mining Town of Western Riverside County

Nestled in the rugged hills between Perris and Lake Elsinore, the Pinacate Ghost Town stands as a forgotten relic of western Riverside County’s mining heritage.

You’ll find this vanished settlement 5-8 miles southwest of Perris, positioned along the former California Southern Railroad line established in 1882.

This forgotten history began when gold was discovered in the 1850s, with the Good Hope vein later uncovered in 1874.

The district’s mining legacy includes operations at Argonaut, Brady, Colton, and nine other mines that collectively yielded 104,000 ounces of gold through 1959.

The boom years lasted until 1903, with brief revival attempts in the 1930s before underground flooding sealed the Good Hope Mine’s fate.

The area is geologically characterized by Santa Ana Formation rocks including shales, slates, phyllites, and quartzites dating to the Triassic period.

Tom Hudson’s comprehensive historical account published in 1988 provides valuable insights into the Lake Elsinore Valley region that includes the Pinacate Mining District.

From Boom to Bust: Pinacate’s Gold Rush Era

The Pinacate Mining District‘s gold rush era unfolded through three distinct phases, transforming a quiet stretch of western Riverside County into a bustling hub of mineral extraction.

Initially, Mexican miners employed primitive mining techniques like arrastras during the 1850s, extracting placer gold.

The second phase began in 1874 with the discovery of the Good Hope quartz vein, launching industrial-scale operations. By 1881, the California Southern Railroad‘s arrival enabled construction of a five-stamp mill, later expanded to twenty stamps. The mill operations were frequently hindered by inefficient water supply, affecting overall productivity.

The final phase saw decline after 1903 as mining depths reached 575 feet and water flooded the shafts. Despite producing 104,000 ounces of gold worth millions, attempts to revive operations in the 1930s failed.

As miners dug deeper, water conquered gold dreams, drowning fortunes that even Depression-era desperation couldn’t resurrect.

What remains today is a ghost town—silent testimony to the boom-and-bust cycle that defined California’s gold country.

The district’s ore contained high-grade deposits with gold content averaging ½ to 1 ounce per ton in quartz veins throughout the region.

Geographical Setting and Railroad Connection

Situated at coordinates 33°45′36″N 117°14′00″W in Riverside County, Pinacate occupies a distinctive position within California’s Colorado Desert, a subregion of the broader Sonoran Desert ecosystem.

You’ll find this ghost town nestled amid rugged topography of northwest-to-southeast mountain ranges and alluvial basins, shaped by tectonic forces at the North American and Pacific plates’ interface.

Pinacate’s desert isolation presented significant transportation challenges throughout its history.

The area lies within the historically significant Pinacate Mining District, known for its mineral extraction operations in the late 19th century.

No railroad ever reached the settlement directly, forcing residents to rely on unpaved desert trails and wagon roads for movement of goods and people.

This lack of rail access—while other mining towns connected to the expanding railroad network—severely limited Pinacate’s economic development and ultimately contributed to its abandonment as miners sought locations with better infrastructure.

The Good Hope Mine: Pinacate’s Golden Heart

At the heart of Pinacate’s brief but significant mining history stands the Good Hope Mine, discovered in 1874 when prospectors identified a promising gold-bearing vein that would transform the district’s economic trajectory.

Initially worked by Mexican miners using simple arrastras, the operation soon shifted to American ownership with more sophisticated methods.

You’ll find the Good Hope’s mining legacy impressive—it produced approximately $2 million in gold (period values), representing nearly one-third of Southern California’s total gold production.

The mine reached depths of 500-575 feet with multiple levels spaced 100 feet apart.

Twenty stamp mills crushed granodiorite ore yielding up to one ounce of gold per ton.

The mine’s underground workings featured a 350 feet deep shaft with drifts extending at the 95 feet and 166 feet levels.

The Pinacate District represents one of the significant precious metal sites in Riverside County, where mining activities often intensified during wartime resource shortages.

This operation remained active until 1936, cementing its place as Pinacate district’s most significant contributor.

Geological Features That Sparked a Mining Frenzy

You’ll find Pinacate’s mining frenzy was triggered by the discovery of gold-bearing quartz veins nestled within the Triassic Santa Ana Formation.

These rich veins, yielding between 0.5 to 1 ounce of gold per ton, created economic opportunities that transformed the quiet landscape into a bustling mining district.

Unlike the volcanic formations found in Mexico’s Pinacate biosphere reserve, the California site offered different geological assets for exploitation.

As miners worked deeper into the earth, they encountered increasing concentrations of sulfides, presenting both challenges and new possibilities for extraction methods. The economic value of cinder mining became apparent in the 1960s when materials were needed for major construction projects in the region.

Gold-Bearing Quartz Veins

The remarkable gold-bearing quartz veins of Pinacate served as the geological catalyst for the area’s mining boom, presenting complex mineral systems that challenged and rewarded prospectors in equal measure.

These veins, striking northwesterly with steep 80° dips, contained free-milling gold alongside increasing sulfide content at depth.

You’ll find the richest deposits occurred primarily in the Good Hope Mine, where veins branched irregularly through granodiorite and quartz latite host rocks.

The gold extraction process became progressively more difficult as miners followed these veins to 575 feet, encountering ore with 0.5 to 1 ounce per ton.

The mineral composition featured gold intimately associated with arsenopyrite in quartz gangue, requiring specialized milling techniques.

High-grade pockets typically formed in foot-wall streaks, where lens-shaped bodies created concentrated zones that fueled Pinacate’s reputation as a profitable mining district.

Triassic Formation Deposits

Beneath the rugged terrain of Pinacate lie the ancient Triassic Santa Ana Formation deposits that ignited the area’s legendary mining frenzy.

These geological treasures consist primarily of shales, slates, and phyllites that underwent significant metamorphism, creating the perfect conditions for gold-bearing quartz veins.

The mineralization characteristics that drew miners to this remote location include:

- Native gold concentrations of 0.5-1 ounce per ton in quartz veins with kaolin

- Increasing sulfide content at greater depths, enhancing ore value

- Structurally controlled deposits along fault lines and fractures

- Proximity to intrusive quartz diorite and granodiorite that drove hydrothermal activity

You’ll find these Triassic deposits strategically positioned within folded and faulted sequences, making Pinacate one of western Riverside County’s most productive historical gold districts.

Increasing Sulfide Depth

As miners explored deeper into Pinacate’s quartz veins, they encountered a fascinating geological phenomenon that would ultimately shape the area’s mining fortunes: increasing sulfide mineralization with depth.

Near the surface, you’d have seen gold gleaming in quartz with minimal sulfides. But as miners pushed downward, the Good Hope vein revealed increasing concentrations of pyrite, arsenopyrite, and other sulfide minerals.

These sulfide challenges transformed mining profitability, requiring finer crushing and more complex processing methods. The ten-stamp mill struggled with separation as water shortages compounded efficiency problems.

The geological structure grew more complex too—surface fissures merged into irregular veins with unpredictable foot-wall shoots.

Despite these rich ore streaks, the overwhelming sulfide content eventually made deep mining economically unfeasible, culminating in the flooding and abandonment of the Good Hope mine.

Life in a California Mining Settlement (1880s-1900s)

If you’d visited Pinacate during its heyday, you’d have witnessed miners trudging to work in three shifts, their faces illuminated only by carbide lamps as they descended into narrow shafts where temperatures often exceeded 100°F.

Mining families occupied simple wooden structures alongside boarding houses for single men, with wives maintaining households through water hauled from communal wells and children attending one-room schoolhouses when available.

After grueling workdays, you might’ve found miners seeking distraction in the town’s saloons, participating in occasional dances at the community hall, or gathering for holiday celebrations that temporarily unified the ethnically divided settlement.

Daily Mining Routines

The daily mining routine in Pinacate began promptly at 7:00 a.m., when laborers reported for what would become increasingly longer shifts as operations grew more industrialized.

Worker schedules evolved from simple placer mining to complex industrial operations running 18 hours daily, seven days a week. You’d find yourself rotating through different tasks, with double jacking requiring position changes every 15 minutes to prevent exhaustion.

- Muckers shoveled crushed rock into ore cars, filling up to 18 cars during ten-hour work days.

- Single jackers struck four-pound hammers 50 times per minute while holding drill steel.

- Double jackers alternated swinging eight-pound sledges about 25 times per minute.

- Timbermen wore bib overalls to protect against splinters while installing tunnel supports.

As mining techniques advanced, your daily routine would include operating dredges with revolving screens and shaking tables.

Workers and Families

Beyond the grueling mining routines, a complex social fabric developed in Pinacate’s makeshift community. You’d find a diverse population of Anglo-Americans, Mexicans, and Chinese residents living in crude wooden shacks and tents without running water or proper sanitation.

Family dynamics revolved around traditional roles—women managing cramped households while men risked their lives in the mines. Children split their time between limited schooling and contributing to family survival. The harsh realities of mining culture meant that single men outnumbered families, especially during boom periods.

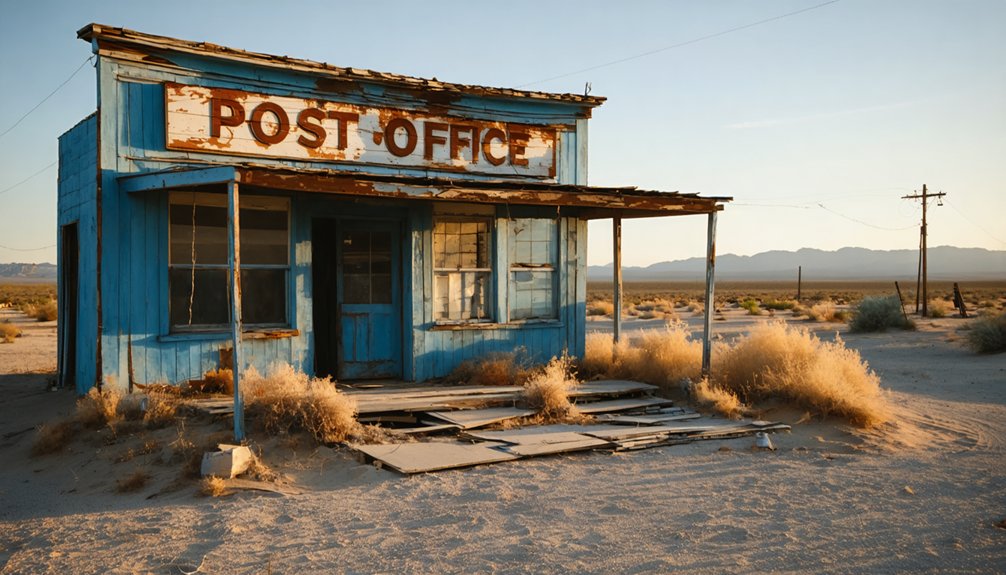

When you weren’t working, you might gather at the general store, post office, or attend church functions that provided rare respite from isolation.

Despite ethnic tensions and social stratification between owners and laborers, community bonds formed through shared hardships and mutual dependence.

Leisure and Entertainment

Despite exhausting workdays, Pinacate’s residents carved out precious moments for leisure activities centered around three main social hubs: saloons, community halls, and the great outdoors.

Your recreational activities would vary with the seasons and your personal interests.

- Saloons served as more than drinking establishments—they offered gambling, impromptu music, and functioned as de facto community centers where miners gathered after shifts.

- Weekend social gatherings featured dances, communal meals, and traveling performers who brought theatrical shows to this remote outpost.

- Outdoor enthusiasts enjoyed horse racing, baseball games against neighboring settlements, and hunting expeditions into the surrounding hills.

- Musical entertainment ranged from formal performances to spontaneous jam sessions, with fiddles and harmonicas providing the soundtrack to Pinacate’s hardscrabble existence.

Mining Operations and Extraction Techniques

Mining operations in Pinacate underwent significant evolution after the California Southern Railroad‘s arrival in 1881, transforming what had once been simple placer mining into an industrial enterprise centered around the Good Hope Mine.

This rail connection enabled construction of a five-stamp mill that later expanded to twenty stamps powered by coal from Terra Cotta.

The quartz veins you’d encounter at Pinacate yielded 0.5 to 1 ounce of gold per ton, requiring sophisticated ore processing techniques.

At Pinacate, modest gold yields demanded complex processing methods to extract value from each ton of ore.

Miners employed amalgamation with mercury for initial recovery, while concentrating machines attempted to separate valuable sulfides.

Water shortages consistently hampered these mining technologies, reducing recovery efficiency.

When primary operations couldn’t extract all available gold, cyanide treatment of tailings captured remaining values.

Despite these advances, flooding eventually defeated attempts to rehabilitate the mines in the 1930s, effectively ending Pinacate’s industrial mining era.

Why Pinacate Was Abandoned

The gradual exodus from Pinacate began in earnest around 1903, when the Good Hope vein—having been excavated to an impressive depth of 575 feet—finally reached exhaustion.

As ore quality diminished, the economic decline created a domino effect. You’d have witnessed families departing as mining jobs vanished, leading to rapid social disintegration.

- No alternative industries emerged to replace the lifeblood of mining

- The Panic of 1907 crushed remaining investment in this remote outpost

- Harsh desert conditions made self-sufficiency nearly impossible

- Railroad changes disrupted crucial supply lines and market access

Without schools, medical facilities, or sustainable water sources, Pinacate’s fate was sealed.

The town that once bustled with prospectors’ dreams returned to the desert, leaving only scattered foundations to mark its existence.

Visiting the Ghost Town Today: What Remains

When you visit Pinacate today, you’ll find yourself confronting a landscape of scattered fragments rather than a preserved historical site. Unlike restored ghost towns like Bodie, Pinacate offers raw authenticity through its ruins, partial foundations, and mining remnants such as fly wheels and crusher fragments.

Visitor preparation is essential since no amenities exist on-site. Bring water, suitable footwear, and a high-clearance vehicle to navigate the rough dirt roads. The site’s remoteness demands self-sufficiency.

During your exploration, focus on photographing structural remains and mining artifacts. Watch for unstable ground near former adits and mine entrances. Without interpretive signage or guided tours, researching Pinacate’s history beforehand enhances your experience.

The reward? An unfiltered connection to California’s mining past, free from commercial intervention or staged historical recreations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous Historical Figures Associated With Pinacate?

No, you won’t find famous residents associated with Pinacate. Historical connections reveal no documented notable figures directly linked to this mining town during its heyday or subsequent ghost town years.

Did Indigenous Peoples Inhabit the Area Before Mining Began?

Yes, you’re looking at rich Indigenous history spanning 40,000+ years before mining. The O’Odham people and their ancestors established water-centered settlements with tinajas supporting their free movement across this ancestral homeland.

What Happened to Pinacate’s Residents After the Town Declined?

Like seeds scattered by wind, Pinacate’s residents dispersed widely across Southern California after the town’s decline. You’ll find their town legacy in family histories, as resident migration followed railroad and industrial opportunities elsewhere.

Were There Any Major Accidents or Disasters in Pinacate’s Mines?

You won’t find major mining accidents or disaster reports specifically linked to Pinacate’s mines in historical records. The district’s smaller operations apparently avoided the catastrophic incidents that plagued California’s larger mining centers.

Does Pinacate Have Any Paranormal or Ghost Stories Associated With It?

You won’t find documented paranormal accounts for Pinacate in historical records. Despite its abandoned status, no specific ghost sightings or haunted locations have been verified at this forgotten mining outpost.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD9M6MP6RRU

- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/el-pinacate-y-gran-desierto-de-altar-biosphere-reserve

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinacate

- https://westernmininghistory.com/library/536/page1/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-antiquity/article/summary-prehistory-and-history-of-the-sierra-pinacate-sonora/F74F88CDAEC550C5A8F3DF4635E0438F

- https://lacgeo.com/pinacate-gran-desierto-reserve

- https://www.blm.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/Desert_Mining_Final-508-small.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinacate_Mining_District

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-295044.html