You’ll find Piney’s remarkable story in eastern Oklahoma, where it began as the first major Cherokee settlement west of the Mississippi in 1824. The town served as the informal Cherokee Nation-West capital until 1828, later transforming into a bustling mining community with 14,000 residents by 1926. Today, this ghost town‘s quiet streets and abandoned mines tell a complex tale of Native American heritage, economic boom, and eventual decline. Its hidden tunnels and remaining structures hold countless untold stories.

Key Takeaways

- Founded in 1824 as the first major Cherokee settlement west of Mississippi, Piney served as the informal capital of Cherokee Nation-West.

- The town peaked around 1916 with essential services but declined after the post office closed in 1921.

- Lead and zinc mining operations brought 14,000 residents by 1926, with over 1,500 businesses supporting the mining industry.

- Today, Piney exists as a ghost town with few remaining residents and a former school building serving as a community center.

- Extensive underground mining infrastructure, toxic chat piles, and abandoned processing plants remain as environmental hazards.

The Cherokee Settlement Origins

While many Cherokee settlements emerged during the forced relocation period, Piney holds special significance as the first major Cherokee town established west of the Mississippi River. Founded in 1824 in the Arkansaw Territory, you’ll find that Piney’s historical significance stems from its role as the informal capital of the Cherokee Nation-West.

The settlement became a key gathering point for Cherokee migration patterns, serving as both a political and social center for those who’d voluntarily relocated under mounting pressures. The Cherokees created a thriving local economy there, similar to how the Five Civilized Tribes would later establish successful communities before the Civil War. Located on Lovely’s Purchase, straddling what would become the Indian Territory-Arkansas border, Piney represented an essential shifting space where the Cherokee people maintained their governance structures and cultural traditions while adapting to life in a new frontier environment. For researchers seeking specific information about Piney’s history, the town appears in several disambiguation pages that clarify its distinct historical identity.

Life in Early Piney

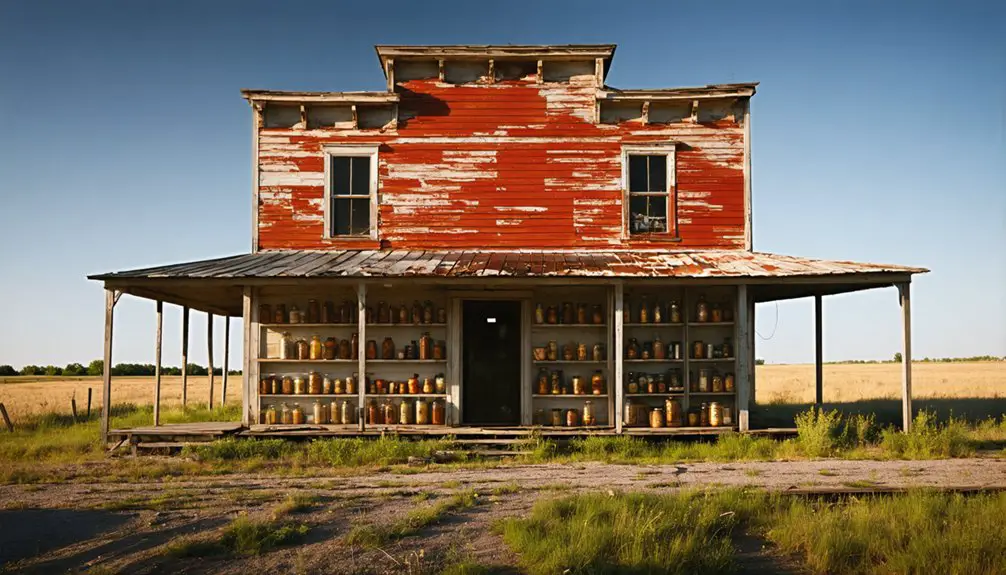

If you’d visited Piney in its early days, you’d have found a vibrant community center anchored by a general store, gristmill, and blacksmith’s shop serving both Cherokee and settler residents.

Like traditional Cherokee settlements, the town organized around council houses where community members would gather to make important decisions.

The town’s post office, established in 1913, and the local schoolhouse demonstrated the community’s commitment to essential services and education.

Located in McCurtain County, Piney emerged during a time when the region was transitioning from Choctaw Nation territory to Oklahoma statehood.

Cherokee Political Center

Although limited records exist about daily life in early Piney, the Cherokee community demonstrated strong social organization through their collective efforts to build essential structures.

Cherokee villages were traditionally organized as autonomous units, operating independently while remaining unified for ceremonies and warfare. The Cherokee Political Center, established in 1966 at Park Hill, now serves as a crucial link to understanding Cherokee governance and cultural preservation from this era. The original three stone columns from the historic Female Seminary still stand at the entrance.

You’ll discover how the community’s political evolution is preserved through:

- Historical markers commemorating leaders like Chief John Ross

- Reconstructed villages showing traditional Cherokee building methods

- Native plant gardens reflecting medicinal and ceremonial uses

- Authentic cultural programs led by trained Cherokee interpreters

The Center’s 44-acre grounds, built on the original Cherokee National Female Seminary site, continue to honor the tribe’s journey from early settlement through modern sovereignty.

Daily Commerce Activities

Since the discovery of lead and zinc ore on Harry Crawfish’s allotment in 1913, Piney’s commercial landscape transformed into a bustling hub of activity centered around the mining industry.

You’d find over 1,500 businesses supporting the daily trade needs of more than 4,000 workers, from equipment suppliers to transportation services.

Local markets and shops clustered near mining operations, making it convenient for you to purchase essentials like food, clothing, and mining supplies.

The extensive trolley system connected you to regional markets in Joplin and Carthage, Missouri, while facilitating the movement of goods and labor.

You’d witness miners and their families participating in informal trading and bartering, creating a tight-knit commercial community.

The town’s population reached peak of 14,000 residents by 1926, creating unprecedented demand for local businesses.

Eateries, boarding houses, and repair shops dotted the streets, serving your everyday needs in this thriving mining town.

As similar locations emerged across the region, Piney required careful place name disambiguation to distinguish it from other mining communities.

Community Building Development

While the Cherokee Nation-West called Piney its informal capital from 1824 to 1828, you’d find the town bustling with tribal council meetings and community gatherings that shaped its early development. Similar to how toxic chat piles permanently altered landscapes in later Oklahoma towns, these early gatherings left lasting impacts on the region’s development.

The heart of community cohesion centered around several key structures that served multiple purposes for social gatherings:

- The schoolhouse, which still stands today as a community center, served as a focal point for education and local meetings.

- A general store that doubled as the post office from 1913-1921, creating a central hub for commerce and communication.

- The Baptist church, where missionary Duncan O’Bryant led religious services until 1834.

- Council meeting spaces that hosted important Cherokee Nation discussions and fostered collective decision-making among tribal leaders.

Political Significance and Leadership

You’ll find Piney’s most significant role was as the informal capital of the Cherokee Nation-West from 1824 to 1828, where tribal council meetings shaped the community’s political landscape.

Much like the EPA’s federal intervention in other towns, the government played a crucial role in shaping Piney’s destiny.

The town’s position within Lovely’s Purchase made it a strategic hub for Cherokee governance until the 1828 boundary changes pushed the official Indian Territory westward.

Your understanding of Piney’s political decline should note how the establishment of Tahlonteeskee as the new Cherokee capital marked the end of the town’s brief but important leadership role in tribal affairs.

Cherokee Council Leadership Hub

Throughout its history, Piney served as an essential political hub within the Cherokee Nation‘s leadership structure, operating as part of the tribe’s extensive council system that today includes 17 district representatives and at-large seats.

As tribal governance evolved, Piney’s influence helped maintain crucial connections across the reservation’s political landscape, contributing to the Nation’s leadership evolution through district representation.

You’ll find these key aspects of Cherokee leadership development in Piney:

- Regional representation in the Council’s committee structure, including Culture, Education, and Health

- Youth engagement through the Tribal Youth Council’s 17-seat system

- Connection to modern facilities like the Innovation Hub in Tahlequah

- Integration with the broader Cherokee political decentralization efforts through district-based governance

Early Government Operations

Building upon its role in the Cherokee Nation’s council system, Piney emerged as a foundational site of Cherokee governance in 1824 when it became the informal capital of Cherokee Nation-West.

You’ll find evidence of early governance in the council meetings that took place here, where Cherokee leaders maintained their political structures despite forced relocation.

The town’s strategic location near Lovely’s Purchase demonstrated Cherokee resilience as they established new administrative systems.

When the 1828 border redefinition placed Piney just one mile from Indian Territory’s eastern boundary, you’ll see how the community adapted by shifting government operations westward.

While the political center eventually moved deeper into Indian Territory, Piney’s leadership legacy lived on through the governance structures they tested here, setting precedents for Cherokee self-determination in the decades that followed.

Territorial Power Shift

While Piney initially flourished as the informal capital of Cherokee Nation-West in 1824, the community faced a dramatic shift when the 1828 territorial boundary redefinition placed it just one mile from Indian Territory’s eastern edge.

This pivotal change in territorial boundaries sparked major alterations in the region’s political landscape. You’ll find these significant developments shaped Piney’s destiny:

- Cherokee leaders relocated their central council to Tahlonteeskee, moving political power westward.

- Most Cherokee residents migrated into designated districts within Indian Territory.

- Political negotiations between Cherokee authorities and U.S. officials intensified.

- Local governance shifted from Cherokee leadership to settler-based systems.

The territorial power shift marked the beginning of Piney’s decline, as federal policies increasingly favored U.S. territorial political systems over indigenous governance structures.

From Bustling Town to Quiet Crossroads

As Cherokee families built their lives in Piney during the 1820s, they couldn’t have known their thriving council seat would one day become a quiet ghost town.

Cultural influences and migration patterns shifted dramatically when the Indian Territory border split the community in 1828, prompting many Cherokee residents to relocate westward to Tahlonteeskee.

You’d have seen Piney reach its peak around 1916, bustling with a general store, post office, gristmill, and blacksmith shop.

The town’s liveliness began fading after 1921 when the post office closed. By 1940, while still incorporated, Piney’s population had dwindled considerably.

Today, only a handful of residents remain near the old school building, which serves as a community center – a quiet reminder of the town’s vibrant past.

Notable Buildings and Infrastructure

Looking beneath Piney’s quiet surface today reveals an extensive network of abandoned mining infrastructure, with an estimated 300 miles of underground shafts sprawling beneath the town and surrounding area.

Historic mining operations left behind a complex legacy of deteriorating structures and environmental challenges that you’ll encounter throughout the former townsite.

Key features that define Piney’s current landscape include:

- Toxic chat piles reaching heights of 200 feet, remnants of lead-zinc processing

- Unstable roads with weight limits and frequent sinkholes from mine collapses

- Abandoned processing plants and ore mills, many now collapsed or demolished

- Environmental remediation infrastructure including soil stabilization projects and contamination monitoring systems

Wire fences and “No Trespassing” signs now restrict access to much of the town, protecting visitors from the hazards of undermined ground and ongoing subsidence.

Legacy of Duncan O’Bryant

When Baptist missionary Duncan O’Bryant arrived in Piney in 1831, he established what would become a transformative presence in the Cherokee Nation-West. His missionary influence extended beyond religious teachings as he founded Liberty Baptist Church, the first of its kind in future Oklahoma, while developing a school that served 40 Cherokee students by 1833.

O’Bryant’s dedication to religious education and community service ended with his death in 1834, leaving behind a widow, nine children, and a congregation that eventually disbanded.

Today, you’ll find his grave – the oldest known in Oklahoma – marking the site where his church once stood. While Piney’s prominence faded after his death, O’Bryant’s pioneering work laid the foundation for subsequent Christian missions to Native Americans in the region.

Present-Day Remnants and Historical Impact

Today in Piney, Oklahoma, you’ll find scattered remnants of what was once a thriving Cherokee settlement and informal capital.

While this ghost town’s official status ended in 1940, its cultural heritage lives on through preserved structures and historical landmarks.

You can still explore several significant sites that tell Piney’s story:

- The old school building, now serving as a community center

- Duncan O’Bryant’s grave from the 1830s, marking early missionary presence

- The general store site, which once housed the bustling post office

- Traces of the original blacksmith shop and gristmill locations

Though few residents remain in the area today, Piney’s importance as an early Cherokee Nation center during territorial changes and westward migration continues to resonate through these physical connections to the past.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Annual Events or Festivals Celebrating Piney’s Cherokee Heritage?

While there aren’t Cherokee festivals specific to Piney, you’ll find major celebrations in nearby Tahlequah, including the Cherokee National Holiday and Cherokee Art Market, which honor traditions connected to Piney’s heritage.

What Natural Disasters or Severe Weather Events Affected Piney Historically?

Through swirling storm clouds and howling winds, you’ll find that recorded tornado history in Piney is limited, though the region’s location in Tornado Alley suggests it likely experienced severe weather events.

How Did Residents Make Their Living Besides Working at Local Businesses?

You’d support your family through subsistence farming techniques, raising livestock, hunting, fishing, crafting homemade goods, and bartering within the community. Many folks also commuted to nearby towns for work.

What Native American Artifacts Have Been Discovered in the Piney Area?

You’ll find flint projectile points, stone drills, and pottery sherds at Native tools sites around Piney. Historic sites contain ceremonial items like decorated ceramics and evidence of trade between indigenous communities.

Were There Any Notable Conflicts Between Cherokee Settlers and Neighboring Communities?

Like waves crashing against rocks, you’ll find Cherokee conflicts erupted frequently with neighboring tribes and white settlers over land rights, horse theft, and resources near the Arkansas-Indian Territory border.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piney

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/picher-oklahoma

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbLyYkx_Kc4

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Piney

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xg8SpCG-wDg

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=SE024

- https://mostateparks.com/sites/mostateparks/files/Cherokee ToT MO.pdf

- https://www.cherokee.org/about-the-nation/history/

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=MC017

- https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/cherokee-553/