Port Wine emerged during California’s 1850s Gold Rush in Sierra County, where Welsh miners established a community balancing religious sobriety with saloon culture. You’ll find the town named after a legendary barrel of port wine discovered by early prospectors. Hydraulic mining ultimately led to Port Wine’s self-destruction, as high-pressure water jets eroded foundations and created sinkholes beneath buildings. The Kleckner Brothers’ store stands as the last significant remnant of this settlement that consumed itself.

Key Takeaways

- Port Wine was established during the 1850s California Gold Rush in Sierra County, attracting Welsh miners who created a unique cultural community.

- Originally known as a “religious and sober town,” Port Wine balanced Welsh cultural traditions with typical Gold Rush establishments like saloons.

- Destructive hydraulic mining practices ultimately led to Port Wine’s abandonment, eroding foundations and creating dangerous sinkholes.

- The Kleckner Brothers’ store remains the last significant structure, featuring brick architecture that served as a merchandise and banking center.

- Mining operations caused severe environmental damage, including mercury contamination and acid mine drainage that continues to affect the area today.

The Gold Rush Origins of Port Wine

When miners struck gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills in early 1850, the settlement of Port Wine quickly materialized as one of California’s promising Gold Rush communities.

You’ll find that Port Wine’s establishment directly coincided with the peak of California’s gold rush, attracting prospectors enthusiastic to try their luck in Sierra County’s rich mineral deposits.

The town’s strategic location placed it at the heart of active mining districts, where miners employed various mining techniques including hydraulic methods and drifting.

They diverted water through elaborate flume systems to expose gold-bearing gravels, fundamentally altering the landscape in their pursuit of wealth.

Port Wine’s population swelled rapidly as news of gold discoveries spread, drawing fortune-seekers from diverse backgrounds who transformed this once-empty stretch of wilderness into a bustling mining hub.

Like other mining settlements, Port Wine suffered from the lawlessness that characterized the early goldfields, with disputes often resolved through informal means rather than established legal processes.

Mysterious Naming: Port Wine’s Barrel Legend

You’ll find the origin of Port Wine’s name shrouded in competing folklore, with some historical accounts claiming miners discovered a barrel of port wine in the bushes while others insist it was actually a keg of cognac.

Despite the absence of definitive documentation to validate either claim, this naming controversy has become an integral part of the town’s historical identity.

The legend, regardless of which alcoholic beverage was supposedly found, continues to captivate visitors and historians alike, cementing Port Wine’s unique place among California’s storied ghost towns. The town was established in the early 1850s as mining activities flourished in Sierra County near La Porte. This narrative shares similarities with other gold rush settlements like Bodie State Historical Park, which also preserves the authentic atmosphere of California’s mining era through careful historical preservation.

Barrel Origins Debate

The origins of Port wine’s “Barrel Legend” remain shrouded in historical ambiguity, creating a fascinating intersection of commerce, tradition, and marketing innovation.

You’ll find competing narratives about how barrel branding began, with George Sandeman‘s “GSC” hot iron markings standing as one of the earliest documented examples of wine authentication in the 1800s.

While some attribute the practice to pragmatic British merchants seeking to enhance their commercial standing, others suggest monastic influences in the Douro Valley.

The barrel branding’s historical significance became formalized with the 1876 Trade Marks Registration Act, transforming an utilitarian practice into legally protected intellectual property.

This evolution bridged the physical marking of oak vessels with the modern concept of brand identity, fundamentally altering how Port wine’s authenticity was established and preserved.

Sandeman’s pioneering approach to quality assurance helped distinguish his products during a time when Britain was desperately seeking alternative wine sources due to disrupted French imports during maritime conflicts.

The fortification process that defines Port wine involves adding grape spirit to halt fermentation, resulting in its characteristic sweetness and higher alcohol content.

Wine vs. Cognac

Beyond the branding innovations that distinguished Port barrels lies a more fundamental distinction that often perplexes newcomers to fortified wines—the clear demarcation between Port wine and Cognac despite their shared presence in oak vessels.

You’ll discover these products reflect entirely different traditions and processes. Port wine characteristics emerge from arrested fermentation, where neutral grape spirit (77% ABV) preserves natural sweetness in Portugal’s Douro Valley. This process yields a fortified wine aged in balseiros or pipas, influencing oxidation levels. The winemaking process involves over 50 grape varieties that contribute to Port’s distinctive flavor profile.

In contrast, cognac varieties develop through double distillation of primarily Ugni Blanc grapes in copper stills, followed by minimum two-year aging in French oak. Unlike Port wine which is fortified during fermentation, Sherry follows a different approach by being fortified after complete fermentation. The resulting VS, VSOP, and XO classifications represent a spirit—not a fortified wine.

Though both rely on oak aging for complexity, their protected geographical indications enforce distinct identities that can’t be legally or technically interchanged.

Name Legacy Lives

While historians debate the precise origins of Port Wine’s name, fascinating folklore suggests the California ghost town earned its distinctive moniker when gold miners stumbled upon a concealed barrel in the nearby underbrush during the settlement’s formative years around 1850.

This barrel folklore transcends mere naming curiosity to reveal deeper truths about mining camaraderie and frontier culture:

- The legend emphasizes communal discovery rather than individual achievement.

- It connects Port Wine’s identity to informal social bonds rather than formal institutions.

- The competing wine versus cognac narratives reflect oral history’s fluidity.

- Absent physical evidence enhances the town’s mystique for modern visitors.

The enduring legacy of this mysterious barrel story provides a symbolic gateway into understanding how mining communities formed their collective identities through shared narratives and experiences. Located in Sierra County, Port Wine was once a thriving gold mining community with a rich history that continues to captivate those interested in California’s gold rush era. Today, visitors can explore the area and see stone ruins with hand-chiseled details that showcase the craftsmanship of the era.

Welsh Miners and Cultural Influences

As Welsh miners settled in Port Wine during the mid-19th century, they transformed the cultural landscape of this California mining community, establishing it as what an 1863 observer described as a “religious and sober town.”

The Welsh miners of Port Wine crafted a haven of faith and temperance amid California’s wild Gold Rush landscape.

Their influence extended far beyond mere demographic presence, creating a unique hybrid community where traditional Welsh cultural institutions like the Eisteddfod festivals coexisted with typical Gold Rush establishments such as saloons and boarding houses.

You’ll find Welsh traditions were preserved through the third California Eisteddfod hosted in Port Wine, drawing Welsh participants from surrounding mining areas.

Despite their reputation for sobriety, they balanced cultural conservatism with mining town social life.

The Welsh also brought technical innovations like the Morgans Fan for mine ventilation, and their presence established higher wage standards than other immigrant groups.

Their cultural festivals reinforced community bonds while maintaining distinct Welsh identity.

Daily Life in a Sierra County Mining Camp

Daily life in Port Wine and neighboring Sierra County mining settlements followed rhythmic patterns dictated by harsh environmental conditions and labor demands. You’d rise with the sun for six consecutive workdays, with Sundays reserved for domestic maintenance and social gatherings.

Community structure evolved from primitive canvas shelters to permanent family cabins as operations intensified and seasons changed.

Four essential elements shaped mining camp daily routines:

- Labor organization shifted from small independent partnerships to wage-based employment as mining technology advanced.

- Domestic responsibilities including water collection, meal preparation, and cabin maintenance filled non-mining hours.

- Social interactions centered around music, gambling, and shared reading materials during precious leisure time.

- Family units participated collectively in camp duties, with children assisting in essential chores.

Hydraulic Mining: Boom and Environmental Impact

Hydraulic mining transformed Port Wine’s economic landscape while simultaneously setting in motion environmental consequences that would echo through centuries. These mining techniques employed powerful water cannons to blast hillsides, extracting gold-bearing material with unprecedented efficiency. Operations peaked between the 1850s-1880s, employing hundreds and moving millions of tons of earth annually.

Hydraulic mining revolutionized gold extraction while unleashing ecological devastation that would reshape California’s landscape for generations.

The ecological consequences were staggering. Approximately 685 million cubic yards of debris choked the Yuba River alone, while an estimated 10 million pounds of mercury contaminated waterways—a toxin that persists today in sediments, flora, and fauna.

Rivers altered course, flooding intensified, and downstream farmlands suffered devastating impacts.

The 1884 Sawyer Decision finally halted these destructive practices, marking America’s first environmental injunction, though the legal reasoning centered on agricultural protection rather than ecological concerns.

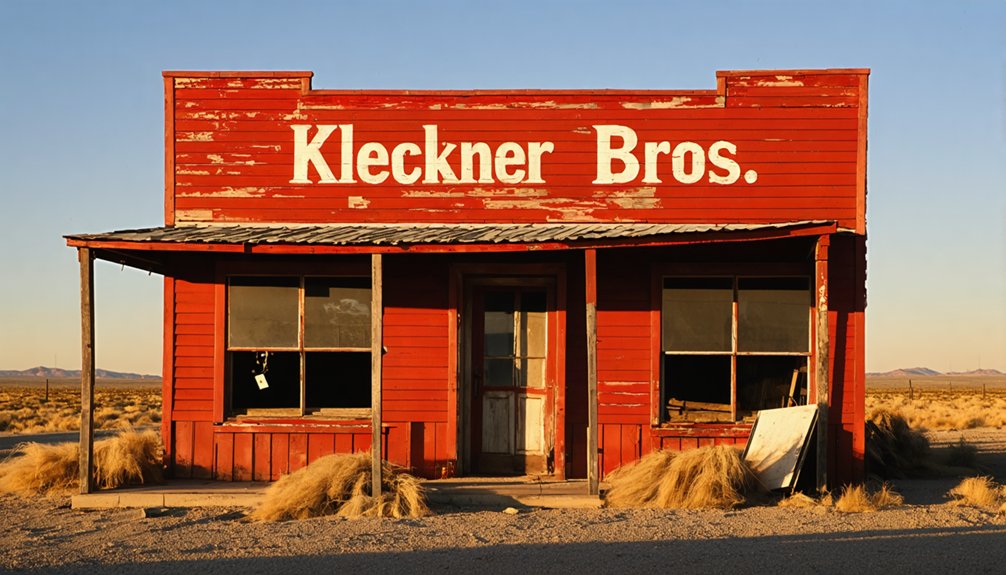

The Kleckner Brothers’ Store: Last Standing Structure

If you visit Port Wine’s remains today, you’ll immediately recognize the Kleckner Brothers’ store by its distinctive brick architecture that has withstood time far better than the settlement’s wooden structures.

The building, originally established as a general merchandise and banking hub for local miners rather than the mistakenly identified Wells Fargo office, served as the commercial center of Port Wine during its 1850s-1860s heyday.

Photographic documentation from the 1930s through recent decades reveals the gradual deterioration of this last relic to Port Wine’s once-thriving commercial district, highlighting the urgent preservation challenges faced by California’s rapidly vanishing mining-era structures.

Architecture and Original Purpose

Among the crumbling remains of Port Wine’s once-thriving Gold Rush community, the Kleckner Brothers’ store stands as the last significant structural evidence to the town’s commercial history.

The building’s architectural significance is evident in its durable stone construction and reinforced iron doors—a demonstration of commercial resilience in an era when permanence wasn’t guaranteed.

Though often misidentified as a Wells Fargo building, this structure actually housed Abraham and Amandes Kleckner’s retail operation serving local miners and residents during the 1850s-1860s boom period.

- Stone walls engineered specifically for frontier durability

- Heavy iron doors designed for merchandise security

- Construction techniques superior to surrounding wooden structures

- Design reflecting practical needs of remote commercial enterprise

The building represents how commerce adapted to the harsh realities of Gold Rush mining settlements.

Historic Preservation Challenges

The preservation of Port Wine’s remaining historical legacy faces almost insurmountable challenges, given the profound environmental devastation caused by hydraulic mining operations that literally washed away most of the settlement.

The Kleckner Brothers’ store stands as the final sentinel of this once-thriving community, its survival remarkable amid such wholesale destruction.

Historical documentation efforts have been severely hampered by WWII-era paper drives during the German blockade, when countless Port Wine records were sacrificed to wartime recycling programs.

You’ll find minimal community engagement today, with the site largely unmarked and inaccessible.

The remote location and rugged terrain further complicate preservation initiatives, while lack of funding prevents proper conservation of the store—now a silent witness to both destructive mining practices and the fragility of historical memory.

Photographs Through Time

Photographic evidence forms our primary window into Port Wine’s vanishing history, with the Kleckner Brothers’ stone store commanding central focus as the settlement’s last significant survivor.

This time capsule appears prominently in 1960s color slides showing weathered yet intact walls, rusted iron doors, and abandoned mining equipment—silent witnesses to a bygone era.

The store’s documentation across decades reveals its gradual surrender to nature:

- Late 1960s photographs capture the stone structure with visible shoring timbers

- Aerial views position the store relative to historic mining trenches

- 1970s images show partially collapsed walls amid increasingly wild vegetation

- Modern explorers report ghostly encounters near the iron doors, which remained present despite extensive deterioration

You’re witnessing the visual chronicle of Port Wine’s final landmark slowly returning to earth.

Social Spaces: Saloons and Religious Life

Deeply embedded in Port Wine’s social framework was the fascinating contradiction between its religious reputation and vibrant saloon culture.

Despite being described as “religious and sober” in an 1863 newspaper, the town supported multiple saloons that served as critical social hubs where miners gathered after grueling shifts.

You’d find a unique religious coexistence where Welsh influences shaped moral frameworks while saloons provided necessary recreation. This duality created a complex cultural fabric where churches and drinking establishments both contributed to community cohesion.

Alongside these contrasting institutions, you’d encounter a surprisingly developed urban landscape featuring boarding houses, blacksmiths, and a Wells Fargo Express office.

When hydraulic mining eventually destroyed much of Port Wine, it didn’t just eliminate buildings—it dismantled this delicate social ecosystem where religious life and saloons culture had maintained an unexpected harmony.

Sierra Mountain Recreation and Ski Racing

While Port Wine’s legacy centers primarily on gold mining, its location within the Sierra Nevada places it near the birthplace of American ski racing—an overlooked chapter in California’s sporting history.

Just miles from where miners strapped on 15-foot longboards in the 1850s, you’ll find the roots of a racing heritage that predates most European competitions. The ski culture that emerged from necessity quickly evolved into organized sport, with the world’s first formal championship held in La Porte in 1867.

- La Porte’s 1867 ski championship offered $600 in prize money—a fortune that attracted miners seeking freedom and fortune.

- Early racers achieved speeds of 80+ mph on primitive wooden skis.

- Women joined competitive skiing by the 1930s through Lake Tahoe Ski Club events.

- The Southern Pacific Railway transformed isolated mining activities into accessible recreation tourism.

The Town That Consumed Itself: Destructive Mining Practices

When you visit Port Wine today, you’ll see a ghost town literally consumed by its own economic engine as hydraulic mining destroyed the very hillsides on which buildings stood.

The high-pressure water jets that extracted gold simultaneously eroded foundations, washed away streets, and ultimately forced residents to abandon their homes as the physical town disappeared beneath mining operations.

This self-destructive process left a scarred landscape of eroded terrain and mining debris, creating long-term environmental damage to waterways and ecosystems that persists as a stark reminder of gold rush exploitation.

Mining Swallowed Homes

As destructive hydraulic mining operations intensified throughout Port Wine in the late 1800s, the very ground beneath residents’ homes began to disappear.

This ghost town’s demise came from within, as miners’ quest for gold undermined their own community’s foundation. The town literally consumed itself when extraction techniques destabilized the earth supporting residences and businesses.

The mining impacts manifested in four devastating ways:

- Hydraulic operations washed away hillsides supporting structures, creating dangerous sinkholes.

- Underground tunnels collapsed unexpectedly, swallowing buildings whole.

- Abandoned shafts filled with rainwater, weakening adjacent soil structures.

- Erosion from mining debris flows undermined foundations of remaining structures.

You can still observe these destructive patterns today in the scarred landscape where homes once stood—a reflection of how extraction industries can devour the very communities they create.

Environmental Price Paid

The environmental devastation at Port Wine extended far beyond the destruction of homes and buildings.

You’re witnessing the aftermath of an ecological catastrophe where hydraulic mining stripped entire hillsides bare, removing forests and topsoil while altering watercourses permanently.

The mining consequences linger in poisoned soil and water.

Mercury, used abundantly in gold processing, contaminated the landscape with millions of pounds of toxic material.

Acid mine drainage continues leaching heavy metals into watersheds, while depleted aquifers never fully recovered from the massive water consumption of mining operations.

This environmental degradation created a toxic legacy that persists today.

The freedom that miners sought came with costs they couldn’t have foreseen—unstable terrain prone to landslides, contaminated drinking water, and ecosystems struggling to recover from systematic destruction a century later.

Archaeological Remnants and Historical Preservation

Despite over a century of natural deterioration and human interference, Port Wine‘s archaeological remnants offer researchers and visitors a tangible window into California’s Gold Rush era.

The archaeological significance lies primarily in building foundations, hydraulic mining equipment, the Kleckner Brothers store, and the town cemetery—each representing different aspects of 19th-century mining life.

- The cemetery provides invaluable genealogical data connecting modern descendants to their Gold Rush ancestors.

- Building foundations reveal urban planning patterns typical of boom-period mining settlements.

- Mining equipment remnants document technological evolution in resource extraction methods.

- The preserved store building offers architectural insights into commercial structures of the era.

Current preservation strategies remain limited by funding constraints, leaving these historical treasures vulnerable to further degradation without more extensive conservation efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Surviving Descendants of Port Wine Residents Today?

Yes, descendant interviews confirm numerous living descendants who maintain family histories. They’ve shared genealogical records, contributed to cemetery preservation, and documented their ancestral connections to the settlement.

What Happened to the Original Port Wine Cemetery?

You’ll find the original cemetery has survived, though weathered, with visible markers documenting Port Wine’s 1850s residents. Its continued existence serves as a proof of the site’s historical significance despite vegetation encroachment.

Was Port Wine Connected to Other Ghost Towns by Rail?

The iron rails, like arteries of commerce, never actually connected Port Wine to other ghost towns. Historical evidence contradicts claims of Sierra Valley Railroad linkages in this region’s ghost town transportation network.

Did Port Wine Experience Any Significant Natural Disasters?

You’ll find no evidence of earthquake impacts or flood aftermath in Port Wine’s history. The town’s decline stemmed primarily from mining-related economic and environmental factors rather than natural disasters.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness in Port Wine?

You’d expect mysterious disappearances and notorious outlaws in a mining town, but surprisingly, historical records don’t document any significant crimes or lawlessness in Port Wine despite its multiple saloons and transient population.

References

- https://thevelvetrocket.com/2010/07/13/california-ghost-towns-port-wine/

- https://www.altaonline.com/dispatches/a62686535/ghost-towns-california-haunted-places-lauren-markham/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4UPnefUpcVM

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/ca/portwine.html

- https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/california-city-planned-community-explained-18476273.php

- https://thevelvetrocket.com/tag/port-wine/

- https://thisdayinwinehistory.com/wine-history-during-the-california-gold-rush/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_gold_rush

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ca-napawineries/