Quartzburg, California, Mariposa County is an intriguing ghost town that once thrived during the California Gold Rush. Nestled in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, it holds tales of prosperity and decline. Below is detailed information about the town.

County: Mariposa County

Zip Code: Not available

Latitude / Longitude: Approximately 37.5017° N, 120.0037° W

Elevation: 2,434 feet (742 meters)

Time Zone: Pacific Time Zone (PT)

Established: Circa 1850

Disestablished: Late 19th century

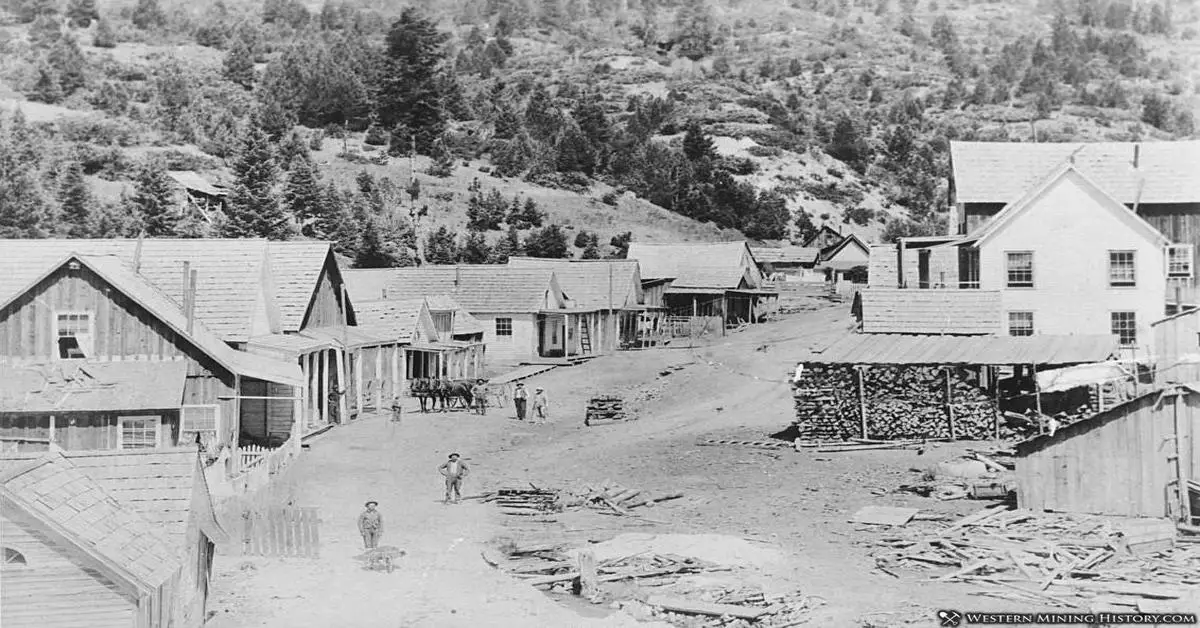

Comments: Quartzburg was established during the height of the gold rush, drawing miners with the promise of riches. The town grew rapidly with the influx of prospectors and their families, creating a bustling community centered around gold mining. Over time, the gold began dwindling, leading to the town’s decline as miners moved to more prosperous areas.

Remains: Today, only a few remnants of Quartzburg exist, primarily consisting of scattered foundations and mining equipment. These remains are a tribute to the once-thriving community and its pivotal role in California’s history.

Current Status: Quartzburg is a ghost town, with no permanent residents. It occasionally attracts history enthusiasts and explorers interested in the remnants of California’s gold rush era.

Remarks: Quartzburg’s legacy poignantly reminds us of the transient nature of mining towns. While the gold rush era brought temporary prosperity, it also left behind ghost towns like Quartzburg, which now serve as historical sites that capture a unique period in American history. Today, Quartzburg stands as a symbol of the adventurous spirit and the quest for freedom that characterized the era.