You’ll find Quincey’s ghost town story in Adams County, Wisconsin, where a thriving settlement once stood at 43°52′35″N, 89°57′22″W. The community developed around Judge Snow’s post office in 1854 and grew through lumber operations and farming. In 1948, the Wisconsin River Power Company’s Castle Rock Lake project submerged the entire town beneath 16,640 acres of water. Today, this underwater settlement holds mysteries beneath Wisconsin’s fourth-largest inland lake.

Key Takeaways

- Quincey was a Wisconsin town established after 1848 that became submerged beneath Castle Rock Lake during the 1948 reservoir project.

- The town flourished through lumber operations and farming until its post office closed in 1915, marking the beginning of its decline.

- Castle Rock Lake’s creation flooded 16,640 acres, transforming Quincey into an underwater ghost town and forcing residents to relocate.

- Families dismantled their homes and held farewell ceremonies before the flooding, permanently dissolving the community’s physical presence.

- The ghost town’s location is recorded at 43°52′35″N, 89°57′22″W, now lying beneath Wisconsin’s fourth-largest inland lake.

The Rise of a Small Wisconsin Settlement

As Wisconsin emerged from its territorial status in 1848, the small settlement of Quincey took root in Oconto County, following the pioneering footsteps of John Penn Arndt’s 1827 dam and sawmill establishment at nearby Pensaukee.

You’d have found Quincey emerging amid a landscape where Native American territories transformed into settler communities through federal treaties and land acquisitions. The area’s early development paralleled the humanitarian spirit seen in other settlements like Trail of Tears refuge communities.

Like many settlement patterns in northeastern Wisconsin, Quincey’s growth aligned with the region’s rich timber resources and river access. The area’s development gained momentum after Colonel David Jones established a successful lumber operation in 1844.

You’ll recognize how economic opportunities drove population growth, as sawmills and trading routes connected this budding community to wider markets.

The town’s development mirrored the broader expansion happening throughout Oconto County, where industrious settlers carved out new lives from the resource-rich wilderness of the mid-19th century.

Life in Early Quincy (1854-1915)

Life in early Quincy centered around a bustling network of postal services and agricultural activities from 1854 to 1915.

You’d find Judge Snow managing the post office, which served as a crucial hub for postal communication linking your community to larger towns.

While working your land, you’d rely on the developing rural infrastructure – from pioneer roads to railroad connections – to transport your crops and receive supplies.

Early farmers depended heavily on evolving transportation networks to move their harvests and obtain essential farming supplies.

During this period, you’d benefit from the grain mills in neighboring towns and Lake Mason’s water power.

The area’s rich soil and drainage patterns were shaped by the terminal moraine line, creating favorable farming conditions in this part of Adams County.

You’d also participate in community life through militia drills during the “Indian Scare” events and support efforts during the Civil War.

As regional transportation routes evolved, you’d witness the gradual shift of services to larger towns, culminating in the post office’s closure in 1915.

Castle Rock Lake’s Creation and Impact

When Castle Rock Lake‘s creation began in 1948, you’d have witnessed the transformation of Quincy’s rural landscape as the Wisconsin River Power Company‘s massive reservoir project submerged local farmlands and prairies.

The flooding from the dam’s completion in 1950 fundamentally altered the community’s geography, creating Wisconsin’s fourth-largest inland lake with a surface area of 16,640 acres where agricultural fields once stood.

Today, much of the surrounding area is preserved within Buckhorn State Park and Castle Rock County Park, maintaining the natural beauty of the region.

You can still find traces of Quincy’s earlier life beneath Castle Rock Lake’s waters, which now stretch 11 miles long and 4.3 miles wide across what was once thriving farmland. The project was completed under the management of Wisconsin River Power Company, which formed in 1947 to oversee the construction and operation of both Castle Rock and Petenwell dams.

Flooding Transforms Rural Community

The completion of Castle Rock Dam in 1951 forever altered Wisconsin’s Central Plain landscape, submerging the historic communities of Germantown and Werner beneath what would become the state’s fourth-largest inland lake.

You’ll find the flooding impacts were extensive, transforming 16,640 acres of farmlands, prairies, and forested knolls into a massive reservoir.

Community resilience shone through as Germantown’s residents, whose town had stood since 1848, largely relocated before the waters rose.

While Werner, primarily a lumber town, had mostly emptied prior to the lake’s creation.

The Wisconsin River Power Company began construction of the dam project in 1947, marking the start of the region’s transformation.

The area’s economic identity shifted from lumber production and farming to hydroelectric power generation and recreational activities. Built on a foundation of sand, the floating-type dam construction represented a unique engineering solution for the region.

Today, where breweries and sawmills once operated, you’ll discover a thriving aquatic ecosystem supporting fishing and tourism, though the heritage of these submerged communities lives on in local memory.

Reservoir Development’s Local Impact

During Castle Rock Lake’s development in the late 1940s, Wisconsin River Power Company launched an ambitious hydroelectric project that reshaped the region’s landscape and economy.

You’ll find the construction milestones moved swiftly: from the permit filing in November 1947 to commercial operation by January 1950, creating Wisconsin’s fourth-largest inland lake at 16,640 acres.

The reservoir ecology shifted as WRPCO maintained strict control over surrounding lands, limiting development while opening areas for public recreation, hunting, and fishing.

Community adaptation meant dealing with new zoning regulations, including mandatory sewage connections and impact fees.

While property values have risen in recent years, you’ll notice the careful balance maintained through development restrictions, preserving open spaces and natural settings that make Castle Rock Lake unique among recreational waters.

The five hydroelectric units installed at the dam could generate substantial power for the region’s growing needs.

The lake’s formation transformed what was previously farmland and forests, dramatically altering the regional topography.

The Final Days Before Submergence

You’ll find a poignant chronicle of Quincy’s final days in the documented exodus of families from their multi-generational homes, as the town prepared for Castle Rock Lake’s waters.

The town council held its last meetings in the community hall, processing final property transfers and coordinating the systematic relocation of residents to neighboring Adams County communities.

Local historians recorded how the remaining townspeople gathered for farewell ceremonies, taking photographs and collecting mementos before their beloved Wisconsin hamlet disappeared beneath the planned reservoir. Before the town’s flooding, the area witnessed one of the most devastating mass killings of passenger pigeons in 1871, when approximately 100,000 people descended on the region to hunt the birds.

Community Exodus and Relocation

As Castle Rock Dam‘s construction progressed through the 1940s, Quincy residents faced the sobering reality that their town would soon vanish beneath Castle Rock Lake’s rising waters.

You’d have witnessed families systematically dismantling their homes, moving their belongings, and bidding farewell to the streets they’d known for generations.

The exodus unfolded gradually as residents coordinated with authorities overseeing the dam project. While some structures were physically relocated, others were torn down before the waters rose.

Community memories and emotional ties ran deep as neighbors scattered to nearby Wisconsin towns, breaking long-standing social bonds. The post office’s earlier closure in 1915 had already signaled the town’s vulnerability, but now the flooding would permanently transform their home into an underwater ghost town.

Final Town Council Meetings

When Castle Rock Dam’s completion loomed near in late 1947, Quincey’s town council convened for their final series of historic meetings in the old municipal building.

You’d have seen council members meticulously working through the logistics of disbanding their community, from infrastructure decommissioning to archiving town records for state repositories. They drafted detailed communications about flooding timelines and resident rights, while establishing help desks to assist families with their changes.

During these last gatherings, final resolutions formally dissolved the municipal governance upon the scheduled flooding date. The council’s closing acts included preserving community landmarks where possible and coordinating commemorative actions near the future reservoir.

In their final proclamations, they acknowledged the sacrifices of long-term residents while documenting the town’s legacy for future generations.

Farewell Ceremonies and Rituals

Throughout Quincey’s final weeks of existence in late 1947, residents gathered for a series of poignant farewell ceremonies that marked their community’s imminent submergence beneath Castle Rock Reservoir.

You’d find neighbors exchanging cherished mementos and documenting their stories through photographs and oral histories, ensuring their legacy wouldn’t be lost to the waters. Local churches hosted special prayer services, while families performed personal blessing rituals at their soon-to-be-abandoned homes.

These farewell traditions included communal meals, candlelight vigils at beloved landmarks, and the ceremonial marking of homesteads with memorial stones. Community bonding remained strong as support networks helped residents cope with their impending displacement.

Social gatherings, including dances and picnics, provided much-needed moments of unity during these emotional final days.

Geographic Legacy and Modern Location

The abandoned settlement of Quincy lies deep within Adams County, Wisconsin, centered near coordinates 43°52′35″N latitude and 89°57′22″W longitude.

You’ll find this ghost town west of the modern Town of Quincy, which sits at 43°53′34″N latitude and 89°54′44″W longitude. The site’s cultural heritage remains preserved in local maps, though physical traces have largely vanished.

Today, the former settlement’s footprint blends into the 32.4-square-mile landscape of rural Quincy town.

The Wisconsin River and Castle Rock Lake reservoir have reshaped the region’s geography, with water now covering 18.17% of the area.

While Quincy Bluff rises 250 feet above the surrounding terrain, much of the original ghost town site has succumbed to natural overgrowth or reservoir development.

Historical Significance in Adams County

As pioneers settled Adams County’s wilderness in the mid-1800s, Quincy emerged as an essential community anchored by its post office’s establishment in March 1854.

You’ll find its historical footprint intertwined with both human drama and natural phenomena, including the massive passenger pigeon nesting of 1871 at Quincy Bluff – an event that tragically contributed to the species’ extinction.

The area’s legacy lives on through local ghost stories and environmental conservation efforts.

After Castle Rock Lake’s creation submerged the original settlement mid-20th century, Quincy transformed from a thriving community into a haunting reminder of progress’s cost.

The town’s submersion sparked numerous local legends, while its surrounding bluffs and natural areas now serve as protected spaces, preserving both the region’s ecological heritage and its mysterious past.

The Memory of Lost Communities

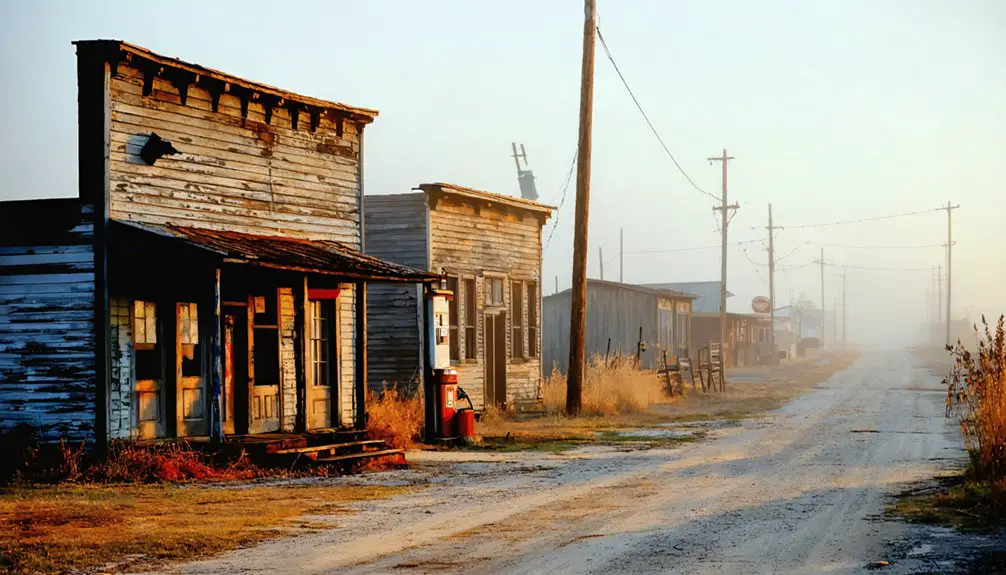

When communities fade into memory, they leave behind more than just physical remnants – they create profound psychological imprints that shape regional identity.

As you explore Quincey’s abandoned structures, you’ll find yourself connecting with the multigenerational stories woven into its weathered walls and empty doorways. The site serves as a powerful mnemonic aid, triggering both personal and collective memories of Adams County’s past.

Memory preservation efforts here aren’t just about protecting old buildings – they’re about safeguarding the emotional archives that connect you to those who came before.

The community nostalgia you’ll experience walking these forgotten streets opens windows into past decades, inspiring a deeper understanding of your regional heritage.

Through Quincey’s quiet ruins, you’re witnessing the tangible connections to your area’s cultural continuity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Artifacts Recovered From Quincy Before the Flooding Began?

You won’t find clear evidence of artifact discoveries before the flooding, as historical records don’t document any organized recovery efforts, though the town’s historical significance suggests items likely remain underwater.

What Happened to the Residents Who Were Displaced From Quincy?

Ever wonder about the human cost of progress? While displacement impacts aren’t fully documented, you’ll find most residents likely moved to nearby Adams County towns, leaving their community memories behind in the 1940s.

Can Parts of Quincy Still Be Seen During Low Water Levels?

You’ll rarely glimpse this ghost town’s underwater ruins during extreme droughts at Castle Rock Lake, but there’s no official confirmation of which structures emerge when water levels drop considerably.

How Much Compensation Did Landowners Receive for Their Flooded Properties?

You won’t find specific compensation records for Quincy’s flood disputes, but Wisconsin’s current programs offer eligible landowners up to $12,000 through the Well Compensation Grant Program for contaminated water supplies.

Did Any Buildings or Structures Get Relocated Before the Flooding?

You won’t find evidence of building preservation or flood mitigation efforts in historical records. Research indicates no structures were relocated before Castle Rock Lake’s waters claimed the settlement’s original location.

References

- https://www.wisconservation.org/ghosts-quincy-bluff-wetlands-state-natural-area/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quincy_(ghost_town)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-vjuqiGWJU

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Quincy_(ghost_town)

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Wisconsin

- https://ocontohistory.org/links/oconto-county-time-line-2/

- http://livinghistoryofillinois.com/pdf_files/History of the city of Quincy

- https://ensignpeakfoundation.org/mormon-quincy-interpretive-center/

- https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lrb/blue_book/2017_2018/160_timeline.pdf

- https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AXVEVWCZ3U4WGF9B/pages/A2O5XDIQTP34SE8Y?as=text&view=scroll