Ray, Arizona was once a thriving copper mining town established in 1909 that reached its economic peak in the early 1900s. You’ll find it was demolished in 1958 when Kennecott Mining Company expanded operations, forcing residents to relocate to the planned community of Kearny. Today, minimal structural remnants exist amid the Sonoran Desert, with limited access due to active mining. The site’s transformation from underground to open-pit mining revolutionized copper extraction economics.

Key Takeaways

- Ray was once a thriving copper mining boomtown established in 1909 that became one of the largest copper reserves in the U.S.

- The town was demolished in 1958 to accommodate expanding mining operations, forcing residents to relocate to the planned community of Kearny.

- Ray featured ethnically segregated neighborhoods with Anglos living in Ray proper while Mexican miners resided in Sonora and Barcelona.

- Few structural remnants exist today, with only scattered foundations, mining infrastructure fragments, and concrete pads visible in the ghost town.

- The site has largely been reclaimed by the Sonoran Desert with limited public access due to ongoing mining operations in the area.

The Birth of a Mining Boomtown (1870-1909)

While Arizona Territory’s mining frontiers were expanding rapidly in the post-Civil War era, the Ray area emerged as a significant mineral prospect when silver mining operations commenced there in 1873.

By 1880, prospectors had identified high-grade copper deposits, establishing the foundation for what would become a thriving industrial center. The economic impact of these discoveries attracted British interests, who organized Ray Copper Mines Company in 1899.

Pioneering prospectors revealed copper wealth that lured British capital, transforming frontier prospects into industrial promise

The turning point came when Daniel C. Jackling’s associates obtained mining options in 1906, leading to the incorporation of Ray Consolidated Copper Company in 1907. Ray Consolidated would eventually yield 86 million pounds of copper annually during the World War I period, demonstrating its critical importance to American industry.

You can trace the town’s formal establishment to 1909, when Arizona Hercules Copper Company constructed a company town supporting underground mining techniques. The town was situated at an elevation of 2,123 feet in Pinal County, Arizona.

exploring the history of Pinal City reveals a rich narrative of industry and community development in the early 20th century. As mining operations expanded, the population grew, leading to the establishment of schools, shops, and other essential services. This evolution laid the groundwork for what would become a significant hub in Arizona’s mining history.

The strategic acquisition of over 2,100 acres positioned Ray for decades of copper production.

Life in the Company Town

You’d find daily life in Ray’s company town strictly ordered by a labor hierarchy that segregated workers based on ethnicity and national origin.

Anglo and Irish workers occupied better housing in Ray proper, while Mexican laborers were relegated to less desirable accommodations in Sonora and Barcelona settlements.

Your working conditions, social mobility, and even basic amenities depended entirely on your position within the corporate structure that controlled every aspect of residents’ lives. This rigid system of labor organization began to face resistance during World War I when early labor activism emerged among the workers in Sonora.

Similar labor challenges were experienced in Globe, where a significant miners’ strike in 1917 became so volatile that federal troops were required to restore order in the mining community.

Daily Working Conditions

Life in Ray’s company town revolved entirely around the demands of the copper mining operation, with every aspect of workers’ daily existence dictated by corporate interests and policies.

You’d begin your day before sunrise, facing working hours that stretched from 8 to 12 hours depending on production demands. Labor conditions varied considerably based on ethnicity, with Anglo and Irish miners typically receiving preferential assignments while Mexican-Americans and Spanish speakers worked in more hazardous positions.

You’d face constant danger from poor ventilation, potential cave-ins, and minimal safety protocols. Your tools consisted of basic hand implements and dynamite, with injury rates soaring above modern standards. The dual-wage system further disadvantaged Mexican miners who earned significantly less for performing the same dangerous work.

The company’s tight control extended beyond working hours—you’d purchase necessities from company stores and receive limited medical care for inevitable respiratory ailments and accidents. At its peak in the early 1950s, the town supported a population of approximately 1,800 residents before its eventual decline.

Social Hierarchy Structure

Despite its seemingly unified façade, Ray functioned as a rigidly stratified society where ethnicity determined nearly every aspect of one’s existence within the company town’s boundaries.

You’d find yourself living in ethnically segregated neighborhoods—Anglos in Ray proper, while Spanish-speaking miners established separate communities in Sonora and Barcelona.

These ethnic divisions extended beyond housing into the workplace, where a clear hierarchy placed Anglos in management and supervisory roles while relegating Mexican and Spanish-speaking workers to lower-tier positions.

Labor disparities were codified through unequal pay scales, limited advancement opportunities, and biased union representation. The town’s social structure mirrored other Arizona mining communities where boom periods created sharp class distinctions.

Even in death, segregated cemeteries preserved the social order. Company officials maintained this system through strict social control, leveraging housing access and store privileges to enforce compliance.

Though separated by these institutional boundaries, communities developed strong internal support networks that occasionally transcended ethnic lines during labor disputes. Women played vital roles in sustaining these communities by operating boarding houses, teaching, and running small businesses that provided essential services.

Economic Heyday and Peak Population

During the early 1900s, you’d witness Ray’s transformation into a thriving economic powerhouse driven by the Ray Copper Company‘s extensive mining operations.

The town’s population swelled to thousands as miners from diverse backgrounds established a multicultural community supported by schools, hospitals, and various services.

You could observe the town’s prosperity directly correlating with copper production levels, which yielded millions in revenue and established Ray as a significant contributor to Arizona’s copper output. The Ray Mine, established in 1882, became one of the largest copper reserves in the United States before the town was eventually displaced. Unlike Tombstone, which became famous as the Town Too Tough to Die, Ray eventually succumbed to the demands of expanding mining operations.

Mining Prosperity Era

As British investors formed Ray Copper Mines Company in 1899, they established the foundation for what would become one of Arizona’s most productive copper operations, marking the beginning of Ray’s mining prosperity era.

Under Daniel C. Jackling’s leadership after 1906, the mine implemented revolutionary mining technology advancements, becoming the first globally to extract over 8,000 tons daily using caving methods developed by Louis S. Cates.

The economic impacts were profound—supporting a population approaching 3,000 people while stimulating the growth of Ray, Hayden, and Kearny as vibrant company towns.

Infrastructure development followed the mine’s success, including transportation networks and social amenities.

With 50 million tons of 2% grade copper reserves initially identified, Ray’s operations supplied the Hayden smelter, creating an economic ecosystem that thrived until mid-century.

Bustling Multicultural Community

While Ray evolved from a small mining settlement into a vibrant company town, its unique multicultural composition set it apart from many contemporaries across the American West.

By the early 1900s, you’d find approximately 2,000 residents in Ray proper, with another 5,000 people living in the adjacent communities of Sonora and Barcelona by 1912.

These segregated settlements reflected the cultural diversity of the mining workforce: Anglo and Irish workers occupied tiered housing in Ray itself, while Mexican and Mexican-American families resided in Sonora, and Spanish immigrants established homes in Barcelona.

Despite physical separation, community cohesion emerged through shared infrastructure—a well-staffed hospital, four churches, educational facilities, and numerous businesses.

This complex social tapestry fostered distinct cultural traditions while supporting the economic engine of copper mining.

Underground to Open-Pit: Mining Evolution

The evolution of mining operations at Ray marked a pivotal change in Arizona’s copper industry when the underground workings developed by Ray Consolidated Copper Company in the early 1900s shifted to an open-pit operation by 1941. This economic change occurred under Ernest R. Dickie’s leadership when underground mining of 2% copper ore became unprofitable.

You’ll find that the mining techniques transformed dramatically during this period. Louis S. Cates initially pioneered caving systems that produced 8,000 tons daily from underground workings.

However, the open-pit method, financed by government loans, allowed for extraction of lower-grade ore at greater volumes and reduced costs. This shift required new earth-moving equipment and created different workforce demands, emphasizing equipment operation over traditional mining skills.

The transformation guaranteed Ray’s economic viability despite fluctuating copper prices.

Daily Life and Community Institutions

Daily life in Ray extended well beyond the operational shifts of the mines, encompassing rich social networks and established community institutions that defined this company town’s character.

Life in Ray transcended the mines, weaving community bonds through shared spaces and institutions.

You’d find several thousand residents during Ray’s early 1900s mining boom, living in company-owned homes that fostered tight-knit relationships. The Cleator Bar and Yacht Club served as a central hub where miners gathered after work, while front porches hosted impromptu community gatherings that strengthened social cohesion.

Multiple schools, a hospital, and likely churches served families’ educational, medical, and spiritual needs.

Water flowed from a spring three miles away through galvanized pipes, while a century-old railroad connected Ray to the outside world. This infrastructure supported the diverse ethnic population that contributed to the town’s cultural richness until its scheduled abandonment between the 1950s and 1965.

The Relocation to Kearny (1958)

By 1958, Ray’s destiny fundamentally changed when copper mining literally consumed the town itself, forcing an unprecedented community migration that would reshape life for thousands.

Kennecott Mining Company’s expansion necessitated the demolition of Ray, Sonora, and Barcelona—symbolized by the destruction of the “Old Man of the Mountain” landmark.

The company contracted Galbraith to develop Kearny, a planned community 11 miles away, as the designated relocation site.

Despite intentions for seamless community integration, numerous relocation challenges emerged. Housing shortages left some families without viable options, while the shift disrupted established ethnic bonds from the original segregated towns.

Final Days of an Arizona Mining Town

As copper deposits beneath the original townsite became increasingly valuable, Ray’s physical landscape underwent dramatic transformation in its final years as an inhabited community.

The encroaching open-pit operations erased iconic landmarks like the “Old Man of the Mountain” while prioritizing industrial efficiency over community resilience. Corporate decisions by Kennecott Copper following their 1933 acquisition ultimately sealed Ray’s fate.

- Witness bulldozers systematically dismantling your childhood neighborhood for ore access

- Experience forced relocation from a multi-generational home due to corporate mining expansion

- Watch as environmental impact from smelter emissions transforms your hometown into uninhabitable terrain

- Feel the dissolution of ethnic communities as families scatter to Kearny, Hayden, or beyond

This community dissolution reflected broader patterns where extractive industries dictated the lifespan of Western mining towns, with economic imperatives consistently outweighing residential stability.

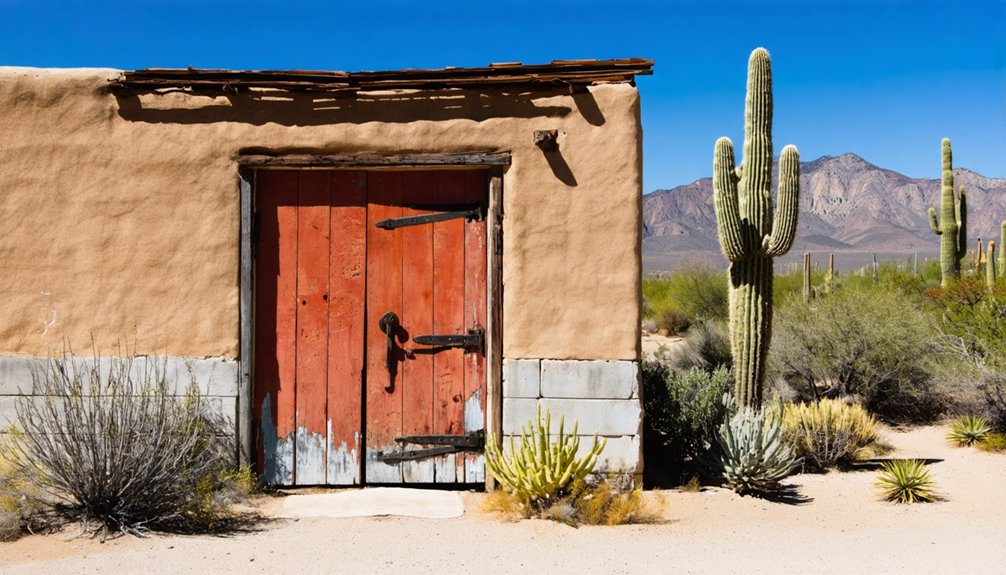

What Remains Today: Exploring Ray’s Ruins

The ghost town of Ray today bears little resemblance to its once-thriving mining community, with minimal structural remnants marking what was once a bustling settlement.

Unlike neighboring ghost towns with intact buildings, your ruins exploration at Ray will reveal primarily scattered foundations and mining infrastructure fragments rather than preserved buildings.

You’ll encounter concrete pads, machinery bases, and occasional industrial remnants—silent memorials to Ray’s mining heritage.

The Sonoran Desert has reclaimed much of the site, with weathering accelerating the decay of less durable materials.

Access remains limited due to proximity to active mining operations.

While nearby ghost towns offer educational exhibits and restored structures, Ray presents a rawer experience focused on industrial archaeology.

Without formal markers or tourism development, the site offers a less curated but perhaps more authentic connection to Arizona’s extractive past.

The Legacy of Ray in Arizona Mining History

Innovation stands at the heart of Ray’s enduring legacy in Arizona’s mining history, transforming the industry through groundbreaking extraction techniques and unprecedented production capacity.

Under Louis S. Cates’ management, Ray developed the world’s first caving system capable of producing 8,000+ tons of ore daily—a revolutionary achievement in copper mining technology.

As you examine Ray’s historical significance, note how it:

- Pioneered large-scale porphyry copper extraction methods that redefined mining economics

- Established the technical foundation upon which modern Arizona copper production still relies

- Represented British-American collaboration in developing Western mineral resources

- Demonstrated how mining innovations could overcome previously insurmountable geological challenges

Ray’s technical achievements transcended its eventual abandonment, cementing Arizona’s reputation as a laboratory for mining technology advancement and industrial copper innovations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Notable Historical Figures Associated With Ray, Arizona?

Like gems in history’s mine, you’ll find several figures tied to Ray’s historical significance: Edward Landers Drew, Tom Graeff, Gory Guerrero, Francisco Miranda, and the Steins—each contributing to Ray’s mining legacy.

What Caused the Most Deaths Among Ray’s Mining Community?

Mining accidents involving blind spots constituted the leading cause of death, particularly from haul truck collisions. You’ll find disease outbreaks represented secondary mortality factors throughout Ray’s operational mining history.

Did Ray Experience Any Significant Natural Disasters During Its Existence?

Shadows of destruction came not from nature but from progress. You won’t find evidence of significant natural disasters in Ray’s history; instead, mining impact itself became the environmental calamity that ultimately consumed the town.

Were There Any Famous Crimes or Lawless Periods in Ray?

Unlike Ruby’s infamous murders, you won’t find well-documented ghostly legends or major crime stories from Ray. Its lawlessness was primarily connected to labor disputes rather than notorious criminal activities.

What Indigenous Peoples Originally Inhabited the Ray Area Before Mining?

Approximately 20,000 Apache people inhabited the region. You’ll find their cultural heritage deeply connected to the Ray area, where indigenous traditions flourished through hunting and gathering practices before mining operations permanently altered the landscape.

References

- https://azgw.org/pinal/ghosttowns.html

- https://greeneandmiranda.wordpress.com/our-towns/ray-sonora/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/arizona/ray/

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-50560.html

- https://arizonapoi.com/ghost-towns/ray/

- https://brotmanblog.com/tag/ray-arizona/

- https://utahrails.net/bingham/kcc-ray.php

- https://www.theirminesourstories.org/post/miners-in-pinal-county-the-growth-and-death-of-company-towns

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ray_mine

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/1883502