To find America’s lost logging towns, start by researching historical societies for maps of timber settlements from 1880-1930. Look for physical remnants like mill foundations, narrow-gauge railways, and company housing layouts. You’ll discover these self-contained communities once housed thousands in the industry’s golden era, with Michigan, Louisiana, and the Pacific Northwest featuring prominently. Exploring these industrial archaeological sites reveals America’s complex relationship with resource extraction and boom-bust economics.

Key Takeaways

- Look for mill foundations, narrow-gauge railways, and company housing layouts as evidence of former logging settlements.

- Research local historical societies for documentation and maps showing the locations of abandoned timber communities.

- Respect private property boundaries as many logging town sites are now on privately owned lands.

- Unsustainable timber practices led to resource depletion and westward abandonment patterns from New England to the Pacific Northwest.

- Preservation efforts through federal agencies and nonprofits help document and protect remaining artifacts of America’s logging heritage.

America’s Forgotten Timber Settlements: How Logging Towns Emerged

As the American frontier expanded westward in the late 19th century, timber companies quietly established isolated communities that would eventually dot the nation’s forested landscapes.

You’d find these company-built settlements in previously untouched wilderness, where timber barons had purchased vast tracts—sometimes exceeding 100,000 acres.

The timber industry impact was immediate and transformative. Companies rapidly constructed mills, housing, and stores in remote areas where no infrastructure existed before.

The wilderness transformed overnight as timber giants conjured instant towns where only trees had stood before.

They recruited diverse workforces, including immigrants and African Americans, relocating them to build instant communities from nothing but surrounding forest.

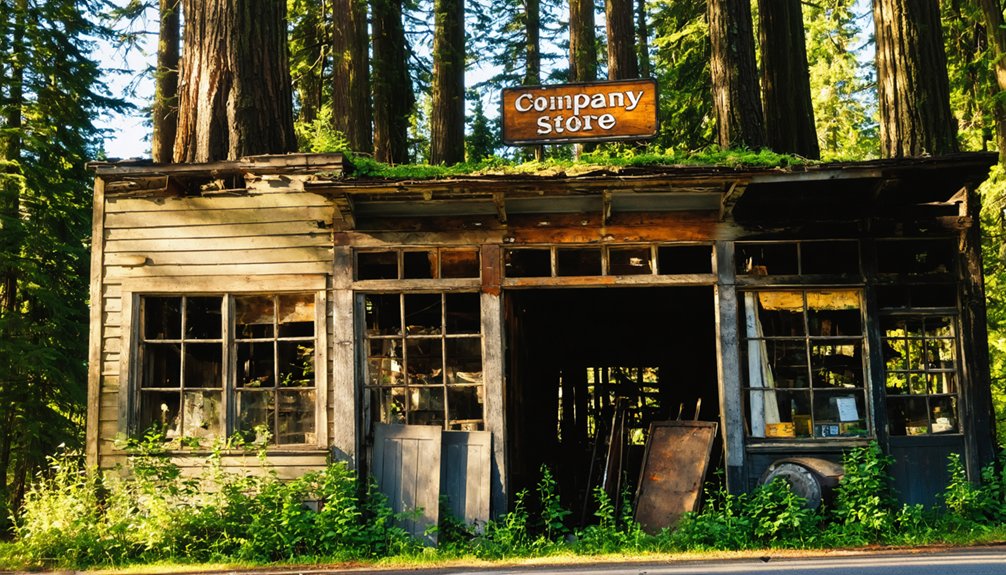

Logging town culture emerged from this controlled environment, where a single corporation functioned as employer, landlord, and merchant. Buffalo City Mills created one such settlement in 1888, becoming northeastern North Carolina’s largest logging operation during its heyday.

Similar to coal mining settlements, timber towns featured distinctive wooden houses, a company store, and shared community spaces where children played freely despite the harsh industrial surroundings.

These forgotten settlements represent a distinct chapter in American industrial history—when corporate interests carved civilization from wilderness while simultaneously controlling every aspect of residents’ daily lives.

The Booming Years: Peak Life in Lumber Communities

During the industry’s golden era from 1880 to 1930, America’s lumber towns transformed into bustling economic powerhouses that forever changed rural landscapes across the nation.

You’d find unprecedented economic resilience as Louisiana’s lumber-related workforce expanded fortyfold, stabilizing the post-Civil War South through robust employment opportunities.

In these booming communities, you’d experience:

- Self-contained societies with housing, medical care, and education through 7th grade

- Populations of several thousand residents served by churches and commissaries

- Incredible productivity with mills cutting up to 1 million board feet daily

- Diverse workforces of both Black and White laborers who migrated for stable wages

Two of the world’s largest sawmills in Louisiana exemplified the lumber industry’s peak, creating instant towns while railroads continually pushed into virgin forests to fuel America’s building needs.

By 1880, Michigan had emerged as the leading lumber-producing state, reflecting the industry’s dramatic westward shift as eastern timber resources became increasingly depleted.

Despite the historical challenges, the logging industry continues to maintain a sizeable workforce of 66,852 people across the United States today.

Behind the Sawdust: Daily Existence in Logging Settlements

In early logging settlements, you’d find a stark contrast between the cramped, often lice-infested bunkhouses where ordinary workers slept and the ornate residences reserved for management families.

During rare moments away from their ten-hour shifts, loggers might engage in card games, storytelling, or music-making, though these activities were heavily restricted in many company towns before union advocacy improved conditions. The emergence of these logging communities was largely driven by necessity as timber extraction operations moved into increasingly remote forest areas where no established towns existed. Workers often spent months at a time completely isolated from their families, enduring what many described as primitive conditions reminiscent of frontier living.

Worker Housing Realities

Behind the romantic notions of frontier life, logging town housing presented a stark reality for timber workers and their families.

You’d find yourself living under complete company control, with your paycheck diminished by housing deductions that perpetuated economic disparities while offering minimal living standards.

Your living quarters revealed the harsh community dynamics of these isolated settlements:

- Single men crowded into bunkhouses with dozens of others, sharing beds in shifts with minimal privacy.

- Family cabins barely exceeding 200 square feet, housing entire families with inadequate sanitation.

- Communal washhouses and outhouses serving dozens or hundreds of residents, fostering health impacts from preventable diseases.

- Structures built hastily from green lumber that warped, leaked, and created fire hazards throughout the community.

Much like migrant farmworkers today, logging town residents faced persistent health issues stemming from unhealthy housing conditions that impacted their overall well-being and productivity. These isolated communities mirrored the plight of modern farm workers who lack access to healthcare due to their remote locations.

Seasonal Leisure Activities

The harsh realities of cramped housing gave way to rich community traditions once work hours ended, revealing how logging towns balanced grueling labor with moments of respite.

You’d witness the “lobby-hog” performers transform evening gatherings into vibrant social centers through jokes, tales, and musical offerings—creating communal storytelling experiences that forged bonds in isolated forests.

As seasons shifted, so did your recreation. Spring meant greasing your legs with lard for dangerous but thrilling log drives during the thaw, while winter evenings featured seasonal gatherings where skilled storytellers gained informal status.

Workers simultaneously built physical endurance and community identity through these shared experiences. These activities provided necessary relief from the physical demands of work in over 450 camps that operated throughout Wisconsin’s forests during peak logging years.

When skidding weather ended or June’s bark-peeling season concluded, you’d join the mass exodus to nearby towns, spending winter earnings before returning to the cycle of work dictated by nature’s rhythm.

The quality of meals was considered essential to maintaining worker morale, with camp bosses understanding that well-fed lumberjacks were more productive and less likely to seek employment elsewhere.

Tracking the Ghostly Remains: Where to Find Lost Logging Towns Today

Wandering through America’s forgotten timber frontiers reveals a haunting landscape where nature has reclaimed once-thriving communities built around sawmills and lumber operations.

While extensive data on logging town remnants remains elusive, dedicated explorers can still discover these vanished chapters of American industrial history.

- Research local historical societies before visiting, as they often document forgotten timber settlements not found in mainstream tourism guides.

- Look for telltale signs of logging infrastructure: deteriorating mill foundations, abandoned narrow-gauge railways, and distinctive company housing layouts.

- Consider seasonal timing – spring offers clearer visibility before vegetation obscures historic preservation efforts.

- Respect private property boundaries, as many logging town sites now exist on lands under various ownership arrangements.

These industrial archaeological sites represent a critical era when America’s resources fueled unprecedented expansion and opportunity.

The Rapid Rise and Fall: Why Logging Towns Disappeared

You’ll find the story of these vanished communities written in the boom-bust economic pattern that defined America’s logging industry from 1880-1920.

As virgin forests fell to axes and saws at unsustainable rates, towns that once bustled with sawmills and lumber camps emptied when nearby timber resources were depleted.

The arrival of steam-powered equipment and railroads initially fueled explosive growth, but ultimately hastened these towns’ demise by enabling rapid resource extraction followed by equally swift abandonment once accessible timber disappeared.

Boom-Bust Economic Cycle

Throughout America’s industrial expansion, logging towns exemplified perhaps the most dramatic boom-bust economic cycle in the nation’s settlement history, rising and vanishing with startling rapidity.

You’d witness these towns transform overnight as railroad expansion revealed virgin forests, triggering waves of labor migration toward promising wages.

Economic volatility was inherent to these settlements, where your prosperity depended entirely on timber markets and resource availability.

Four defining elements of the logging town boom-bust cycle:

- Rapid capital investment followed by equally swift disinvestment once timber was exhausted

- Railroad development that created then abandoned communities when tracks were removed

- Highly mobile workforce that flowed into towns during booms and vanished during busts

- Market demand fluctuations that determined a town’s fate regardless of local conditions

Forest Resource Depletion

You can trace the collapse of timber-dependent communities along a westward path: first New England, then the Great Lakes, the Southeast’s longleaf pine regions, and finally the Pacific Northwest.

As virgin forests disappeared—75% lost since the 1600s—so did the towns built around them.

The establishment of the Division of Forestry in 1885 and the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 marked the nation’s first attempts at timber sustainability and forest conservation, though these came too late for many communities.

Transportation Technology Shifts

While many forces contributed to the demise of America’s logging towns, transportation technology shifts fundamentally transformed the industry’s geography and economics.

When you examine the artifacts of these forgotten communities, you’ll find evidence of dramatic transportation advancements that rendered many settlements obsolete.

- The shift from water-dependent log drives to steam-powered railroads in the 1880s freed logging operations from geographic constraints near rivers.

- Steam donkeys and mechanized equipment increased logging efficiency, allowing companies to extract timber from previously inaccessible terrain.

- Purpose-built logging railroads connected remote forests to major distribution networks, eliminating the need for intermediate settlements.

- By the early 20th century, motorized vehicles replaced animal power and temporary rail lines, enabling logging companies to centralize operations in fewer permanent locations.

Architectural Legacies: What Structures Survived the Exodus

As towns built around the timber industry emptied following the inevitable resource depletion, certain structures managed to withstand both time and abandonment, offering silent testimony to America’s logging heritage.

You’ll find mill buildings standing as the most imposing survivors, their timber frameworks and stone foundations defying decay. Workers’ cabins, bunkhouses, and occasionally a church or schoolhouse remain as cultural anchors amid the forest’s reclamation.

These architectural legacies now benefit from heritage conservation efforts, with national and state landmark designations protecting the most significant examples.

While wooden structures succumb to rot and weather, places like Kennecott and Bodie preserve substantial building collections.

These architectural significances transcend mere ruins—they’re physical connections to the rugged independence that defined America’s resource frontier, where community rose and fell with the forests that sustained them.

Mapping the Timber Trail: Regional Concentrations of Logging Settlements

The geographical distribution of America’s lost logging settlements mirrors the nation’s evolving relationship with its forest resources from the colonial era through industrialization.

You’ll find these ghost towns concentrated along patterns that reflect both ecological opportunity and economic necessity.

When exploring America’s logging legacy, you’ll discover distinct regional clusters:

- Coastal settlements (1620-1850) where European extraction methods replaced Indigenous stewardship

- Checkerboard patterns in the Pacific Northwest, especially Oregon’s Willamette Valley

- Species-specific concentrations around valuable timber like sugar maple and shortleaf pine

- Post-Louisiana Purchase western territories where settlement followed resource availability

Today, timber tourism offers glimpses into these forgotten communities where commerce once thrived around lodgepole pine, Ashe juniper, and chestnut oak.

The distribution of these settlements tells a story of freedom, opportunity, and ultimately, abandonment as resources depleted.

Beyond the Trees: Secondary Industries in Lumber Communities

Lumber communities across America’s forested regions seldom survived on timber extraction alone, instead developing intricate economic ecosystems where secondary industries provided crucial stability and diversification.

While sawmills processed raw logs, you’d find thriving furniture makers, cabinetry shops, and pallet manufacturers transforming lumber into finished products, creating additional employment opportunities that multiplied throughout these communities.

This economic adaptability extended beyond wood products. Specialized transport systems emerged—ports, railroads, and trucking operations—forming critical infrastructure that connected isolated towns to broader markets.

Equipment manufacturing and maintenance businesses flourished alongside timber operations.

Though many historic timber towns have witnessed declining sawmill numbers, community resilience has manifested through shifts to healthcare, retail, public employment, and even renewable energy sectors.

Today’s surviving logging communities reflect this complex economic evolution, preserving their heritage while embracing necessary change.

Preserving Vanishing History: Documentation Efforts of Logging Ghost Towns

While countless logging towns have vanished into America’s forests, dedicated preservation efforts now race against time to document their fleeting existence.

These historical snapshots preserve community traditions and labor practices that defined America’s timber era.

Federal agencies, academics, and nonprofits collaborate to recover these lost chapters through:

- Archaeological surveys that map foundations and collect artifacts from sites like Kennecott, Alaska

- Oral history projects gathering firsthand accounts from descendants who remember the distinctive rhythms of mill work

- GIS technology creating digital reconstructions of vanished town layouts

- Archival research compiling company ledgers and photographs that illuminate daily life

You’ll find these preservation efforts particularly meaningful at places like Falk, California, where the BLM maintains records of a community that once thrived in redwood country.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Logging Towns Experience Significant Crime or Lawlessness?

Yes, your logging towns experienced significant lawlessness. Crime prevalence flourished amid minimal law enforcement, with violence, theft, and vice thriving in these remote, transient, male-dominated communities during the timber boom era.

What Medical Care Was Available in Remote Logging Settlements?

Picture a sparse doctor’s office in a converted cabin. You’d find minimal medical facilities, with company-employed physicians providing basic care. Traveling doctors supplemented healthcare access, while serious injuries required long journeys to distant hospitals.

How Were Women’s Roles Defined in Logging Communities?

You’d find women’s labor centered on cooking, camp management, clerical work, and community support—creating home-like environments while maintaining the social fabric that sustained these isolated, male-dominated 19th-century logging societies.

Did Indigenous Communities Interact With or Work in Logging Towns?

Traditional stewards became marginalized laborers—yes, Indigenous peoples worked in logging towns, though their cultural exchange and labor contributions were often undocumented and undervalued within the settler-colonial timber industry’s hierarchy.

What Happened to Cemetery Sites When Logging Towns Were Abandoned?

When logging towns vanished, you’ll find their cemeteries succumbed to nature’s reclamation—trees piercing gravesites, markers sinking beneath vegetation, and historical significance fading without cemetery preservation efforts to maintain these sacred grounds.

References

- https://www.petoskeynews.com/story/news/local/gaylord/2015/04/07/ghost-towns-left-behind-by-the-earliest-loggers/45205943/

- https://www.visitredwoods.com/listing/falk-historic-logging-ghost-town/526/

- https://www.whitemountainhistory.org/abandoned-towns

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VFfQ0UXln5s

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/08/top-ghost-towns-for-history-buffs.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_ghost_towns_in_the_United_States

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AydgS5_IgDY

- https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/untitled

- https://www.northbeachsun.com/ghost-town-the-forgotten-story-of-dare-countys-buffalo-city/